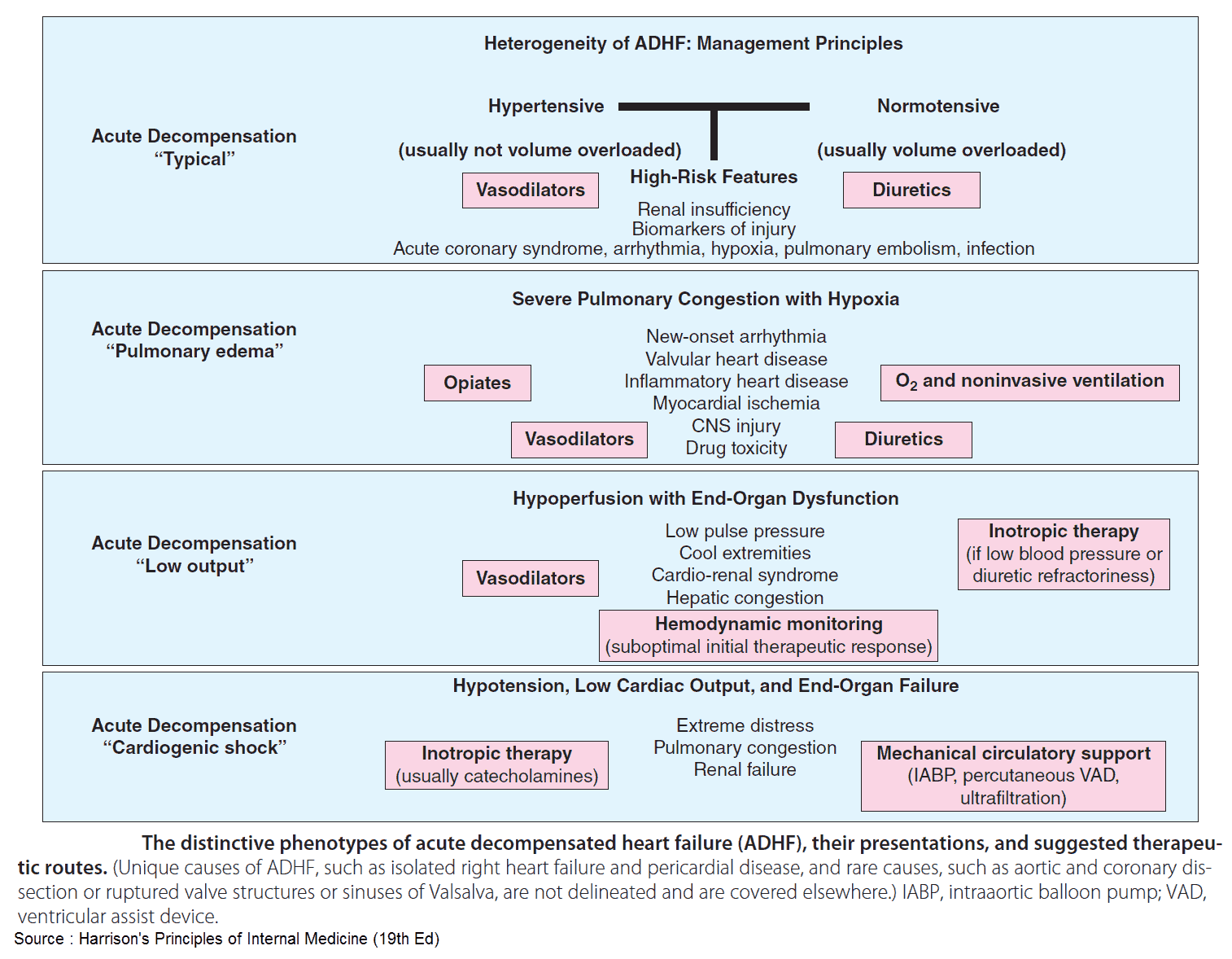

Congestive heart failure is the most common reason for hospitalization among U.S. patients over 65 years of age. Acute heart failure can present in a variety of ways that can be conceptually grouped into two pathophysiologic categories:

- decompensated cardiac failure, the classic accumulation of volume until the patient’s chronically depressed pump function is overwhelmed and

- vascular failure, the rapid increase in afterload through increased systemic vascular resistance leading to increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and decreased cardiac output with subsequent pulmonary edema.

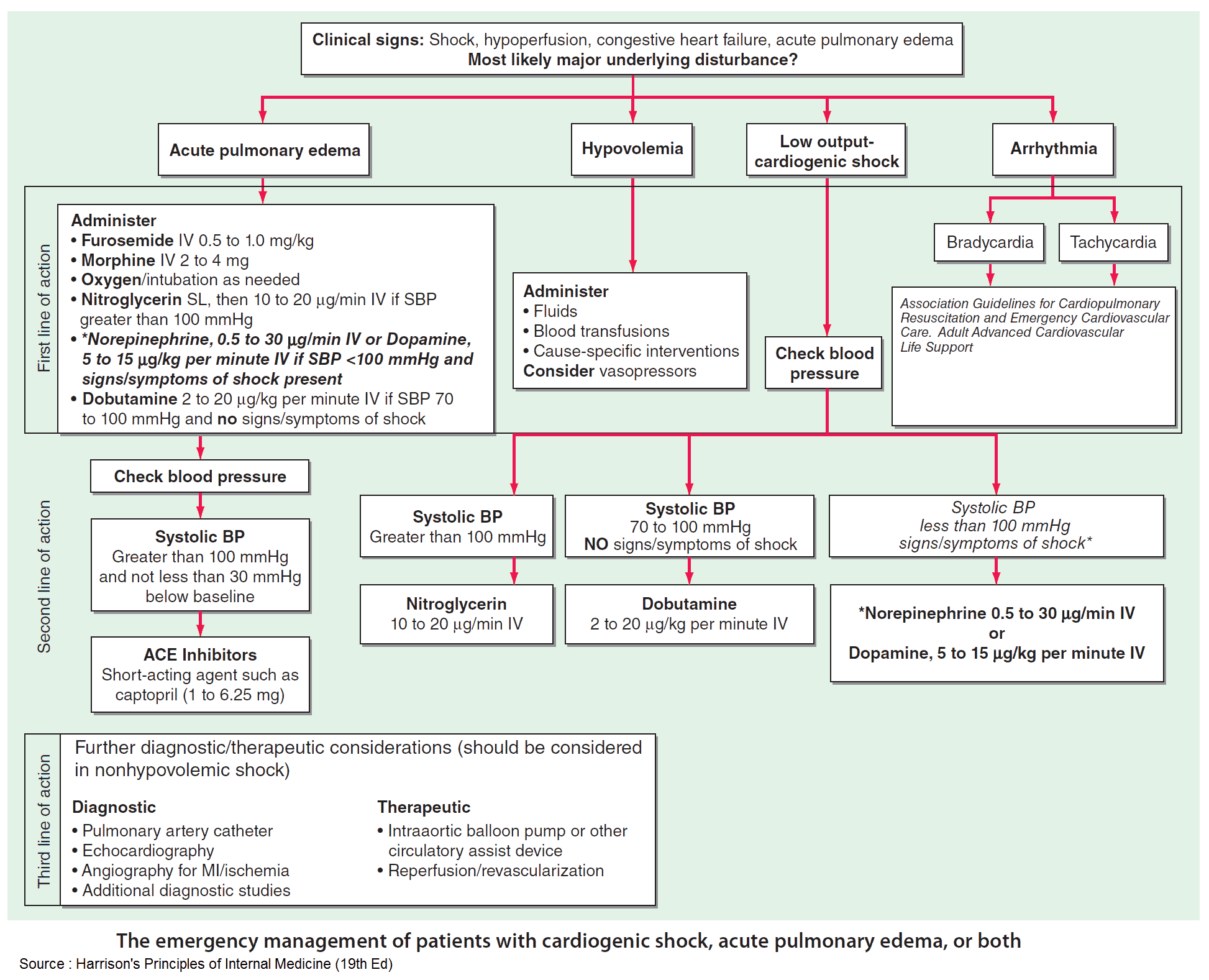

Diuretics have traditionally been a mainstay of therapy for cardiogenic pulmonary edema. They may not be the preferred initial therapy, however, for those patients with vascular failure, who are often euvolemic, or those with cardiogenic shock, who are often hypovolemic.

In these patients, the emergency provider should first optimize preload and afterload reduction with the use of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV), nitrates, or inotropes as indicated.

NPPV in Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema

NPPV is an important adjunct in the treatment of patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema. NPPV decreases preload and afterload by increasing intrathoracic pressure. This decreases venous return (preload) and decreases left ventricular transmural pressure (afterload).

NPPV has been shown to reduce the rate of intubation and in-hospital mortality in patients with acute heart failure. Therefore, early use of NPPV in patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema is warranted in addition to nitrate therapy.

Importantly, no studies have demonstrated a difference in patient-centered outcomes between continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP).

An initial setting of 5 to 10 cm H2O continuous pressure is recommended for CPAP, while an inspiratory pressure of 10 cm H2O and expiratory pressure of 5 cm H2O are recommended as initial BiPAP settings.

Nitrates in in Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema

Nitrates (i.e., nitroglycerin) effectively improve cardiac output for patients presenting with cardiogenic pulmonary edema and hypertension.

- At low doses, nitrates dilate the venous system and reduce preload.

- At higher doses, nitrates produce arterial dilation with resultant afterload reduction.

This combination decreases myocardial oxygen demand, decreases cardiac work, and ultimately increases cardiac output.

Nitroglycerin can be administered first by the sublingual route (with each spray or tablet delivering 400 mcg every 5 minutes) until intravenous access is established and a continuous infusion started. Infusion rates typically begin around 20 mcg per minute, but must be rapidly titrated to clinical effect. In general, the dose can be increased by 40 mcg per minute every 5 minutes to a maximum of 200 mcg per minute.

Sodium nitroprusside is an alternative that may be useful in patient’s refractory to nitroglycerin therapy. Intravenous doses start at 0.1 mg/kg/min and can be increased by 0.1 mg/kg/min every 5 minutes. Unfortunately, its use is limited by the potential for cyanide toxicity, particularly at high doses and in patients with renal dysfunction.

Read More: Aggresive Nitroglycerin Usage in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (ADHF)

Vasopressor in Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema

Though most patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema present with hypertension, some patients may present with hypotension and cardiogenic shock as the etiology of their edema.

Dobutamine is generally the agent of choice in this setting, and an intravenous infusion can be started at 2.5 mcg/kg/min; it can be increased by 2.5 mcg/kg/min to a maximum of 20 mcg/kg/min. It is important to recall that tachydysrhythmias may occur, along with vasodilation and exacerbation of hypotension at higher rates of dobutamine.

In this setting, consider starting a vasopressor medication, such as epinephrine or norepinephrine, to augment systemic vascular resistance. Epinephrine, with its increased effect on beta-1 receptors, may be preferred initially over norepinephrine.

Morphine in Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema

Lastly, it is important to avoid the routine use of morphine for patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Though classically recommended for its theoretical ability to reduce afterload, recent retrospective analyses have demonstrated an association between morphine use and increased rates of intubation and in-hospital mortality. Though no large, prospective trials exist, the routine use of morphine in patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema should be avoided.

As with most patients presenting to the emergency department, diagnosis and management must occur simultaneously. It is helpful to consider two categories of cardiogenic pulmonary edema: decompensated cardiac failure and vascular failure.

If true volume overload is suspected, diuretics and ACE inhibitors can then be added after the administration of nitrate therapy and NPPV.

Key Points

- Early use of NPPV significantly reduces rates of intubation and inhospital mortality.

- Nitrates should be administered early and rapidly to maximize preload and afterload reduction.

- For patients presenting with pulmonary edema secondary to cardiogenic shock, an inotrope such as dobutamine should be initiated to improve cardiac output.

- Recent data suggest worse outcomes with the use of morphine for patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

- Diuretic administration should follow the use of more rapidly acting preload- and afterload-reducing therapies, particularly if there is little suspicion of volume afterload.

Suggested Readings

- Cotter G, Felker GM, Adams KF, et al. The pathophysiology of acute heart failure —is it all about fluid accumulation? Am Heart J. 2008;155(1):9–18.

- Marik PE, Flemmer M. Narrative review: The management of acute decompensated heart failure. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27(6):343–345.

- Mebazaa A, Gheorghiade M, Piña IL, et al. Practical recommendations for prehospital and early in-hospital management of patients presenting with acute heart failure syndromes. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(1 Suppl):S129–S139.

- Peacock WF, Hollander JE, Diercks DB, et al. Morphine and outcomes in acute decompensated heart failure: An ADHERE analysis. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(4):205–209.

- Vital FM, Ladeira MT, Atallah AN. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (CPAP or bilevel NPPV) for cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD005351.