Table of Contents

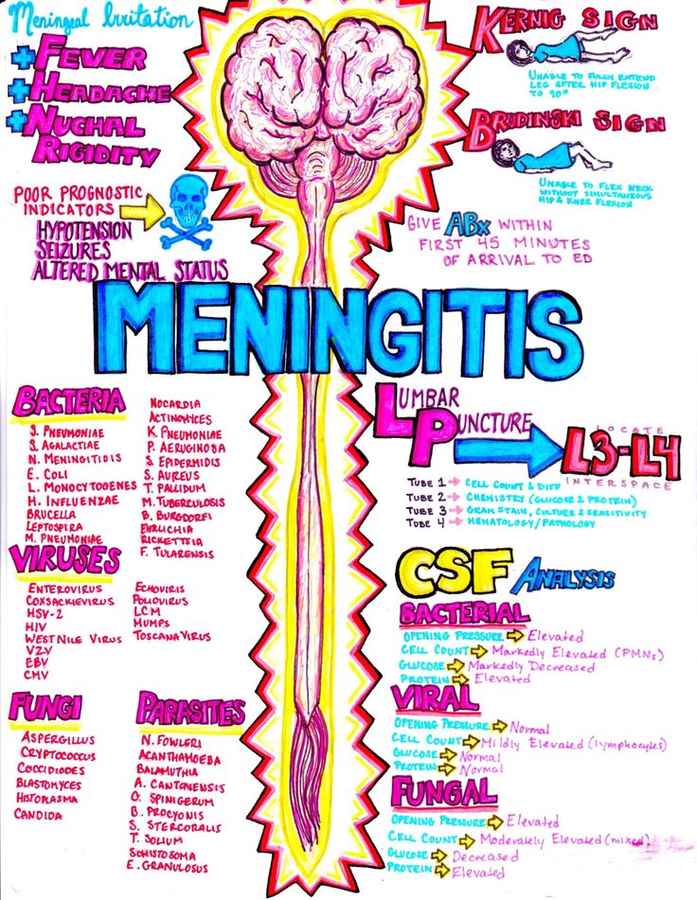

Meningitis can be caused by infectious or noninfectious etiologies. Noninfectious etiologies of meningitis include:

- malignancy

- autoimmune conditions

- medications

- trauma

- iatrogenic procedures.

Infectious meningitis can be caused by a variety of bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic organisms. Bacterial and viral organisms account for the most common types of infectious meningitis. In general, viral meningitis is a self-limited disease that resolves with supportive care. In contrast, bacterial meningitis is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. This chapter will focus on pearls and pitfalls in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with bacterial meningitis.

Physical Examination

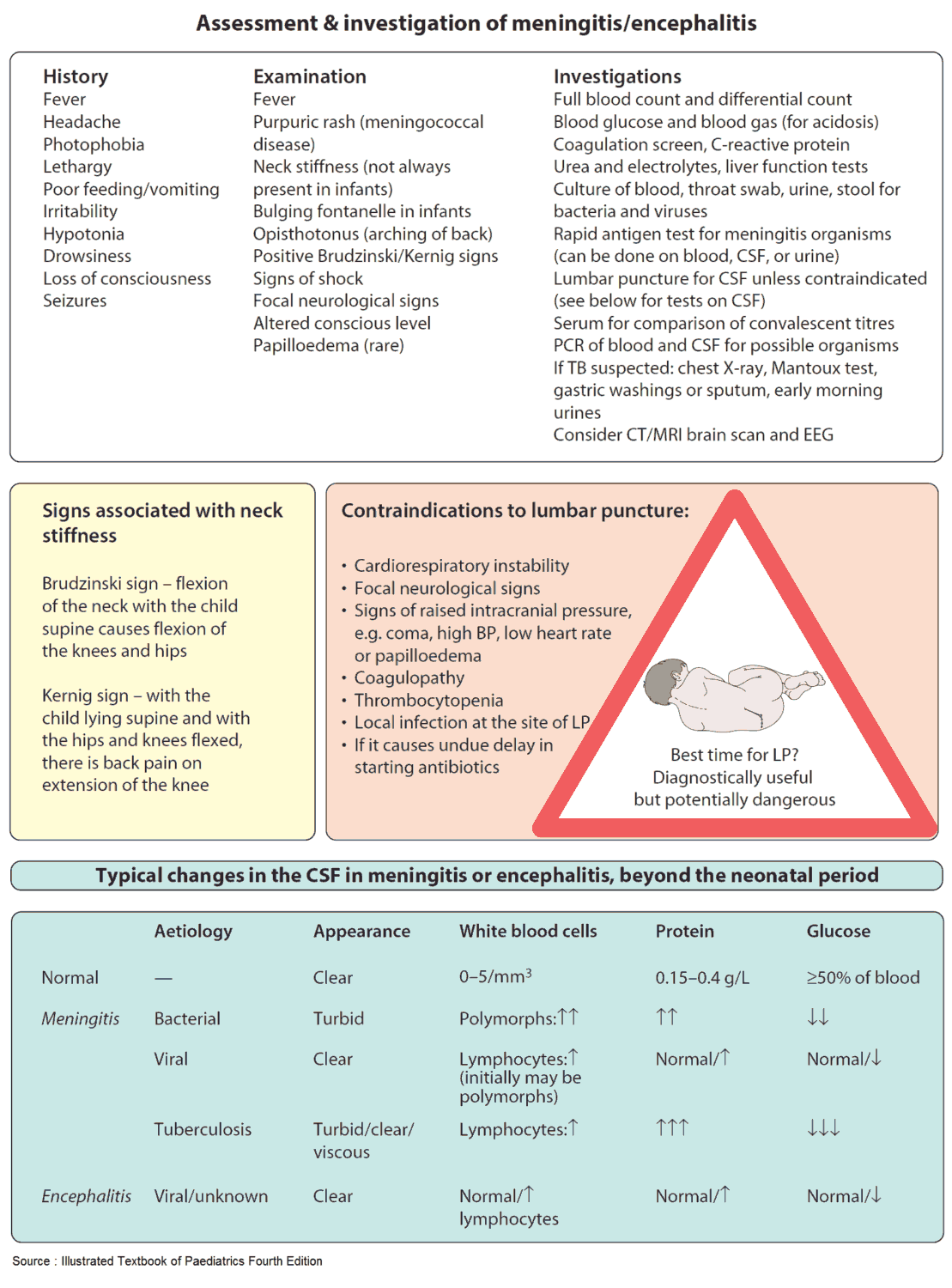

It is commonly taught that patients with bacterial meningitis will exhibit nuchal rigidity, Kernig sign, or Brudzinski sign.

Unfortunately, these classic physical examination findings are of limited value in the evaluation of patients with suspected meningitis. In fact, the sensitivity of Kernig’s, Brudzinski’s, and nuchal rigidity for meningitis is very low; these signs are present in <33% of patients with meningitis. Furthermore, large studies have reported that the classic triad of fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status is present in just 44% to 66% of patients with meningitis.

A comprehensive review evaluated the utility of the physical examination in the diagnosis of patients with confirmed meningitis and found that no individual clinical finding had significant sensitivity or specificity to exclude meningitis. In this study, the highest pooled sensitivities were for headache (0.50, CI: 0.32 to 0.68) and nausea with vomiting (0.30, CI, 0.22 to 0.38).

In contrast to nuchal rigidity, Kernig sign, and Brudzinski sign, jolt accentuation (headache with horizontal rotation of the head at 2 rotations per second) has been shown to increase the probability of meningitis in patients with a fever and headache. In fact, the sensitivity of jolt accentuation in the diagnosis of meningitis has been found to be 100%, with a specificity of 54%.

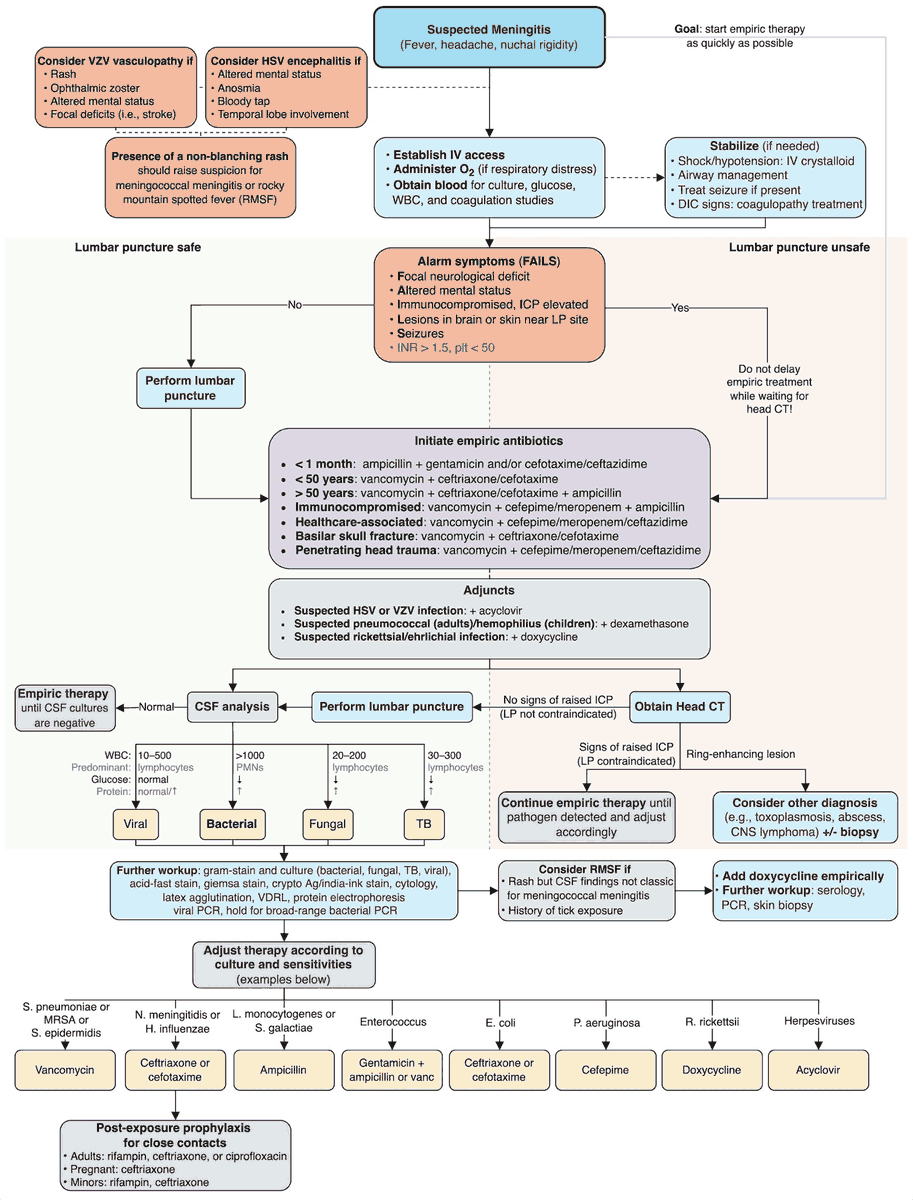

Lumbar Puncture (LP)

Given the limitations of the physical examination, a lumbar puncture (LP) should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of meningitis. If possible, the LP should be performed as soon as possible in order to maximize the diagnostic yield of culture of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The CSF can be sterilized within hours of initiating antibiotic therapy. Importantly, antibiotic administration should not be delayed to perform the LP.

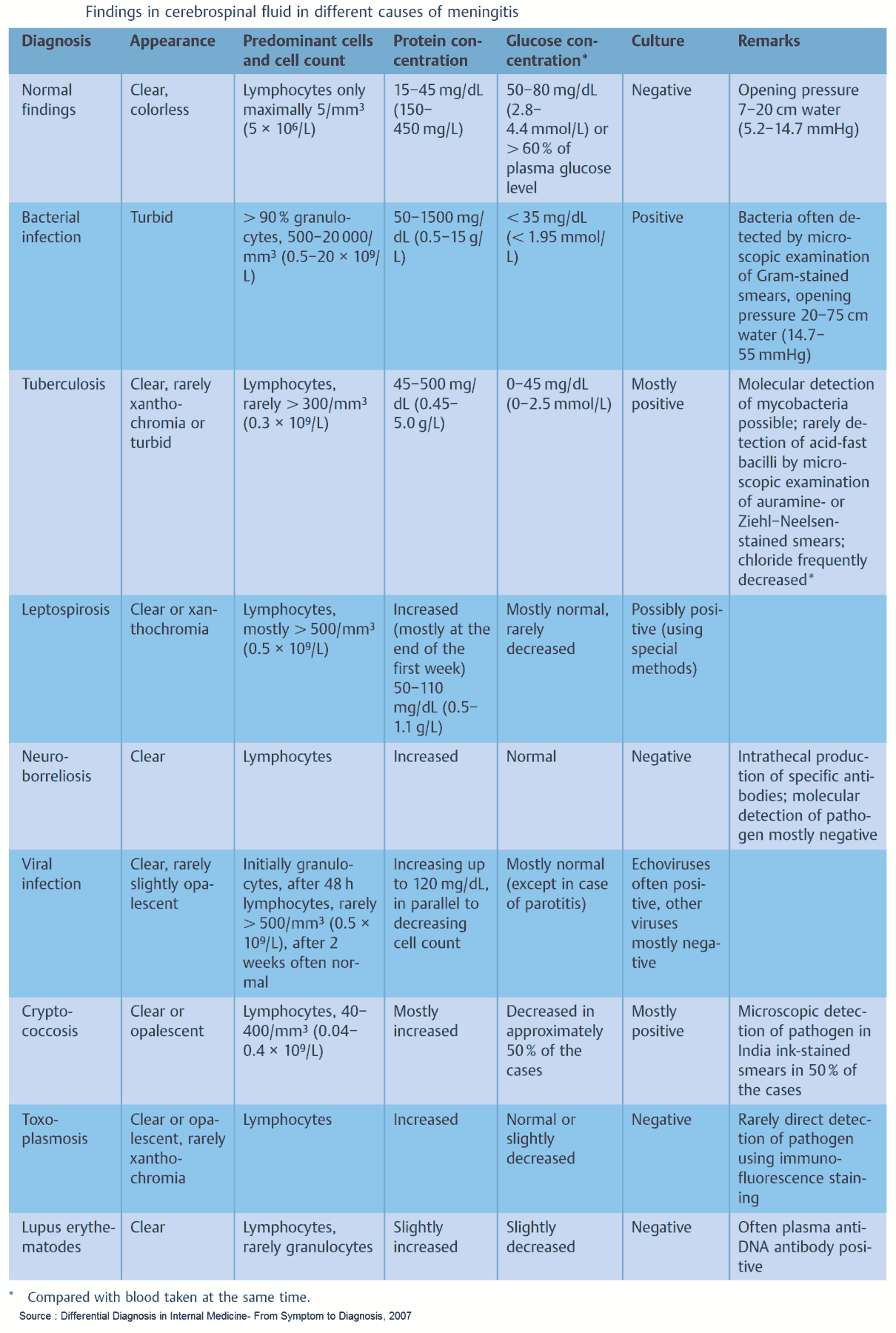

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis

The diagnosis of bacterial meningitis is supported by the following CSF findings:

- An elevated opening pressure

- Cloudy CSF color

- CSF pleocytosis (i.e., elevated white blood cell count)

- Elevated CSF protein

- Low CSF glucose

- CSF glucose-to-blood-glucose ratio of <0.4

These CSF studies should be considered as methods to confirm the diagnosis of meningitis (positive likelihood ratios >10) rather than methods to exclude the diagnosis (negative likelihood ratios <0.1).

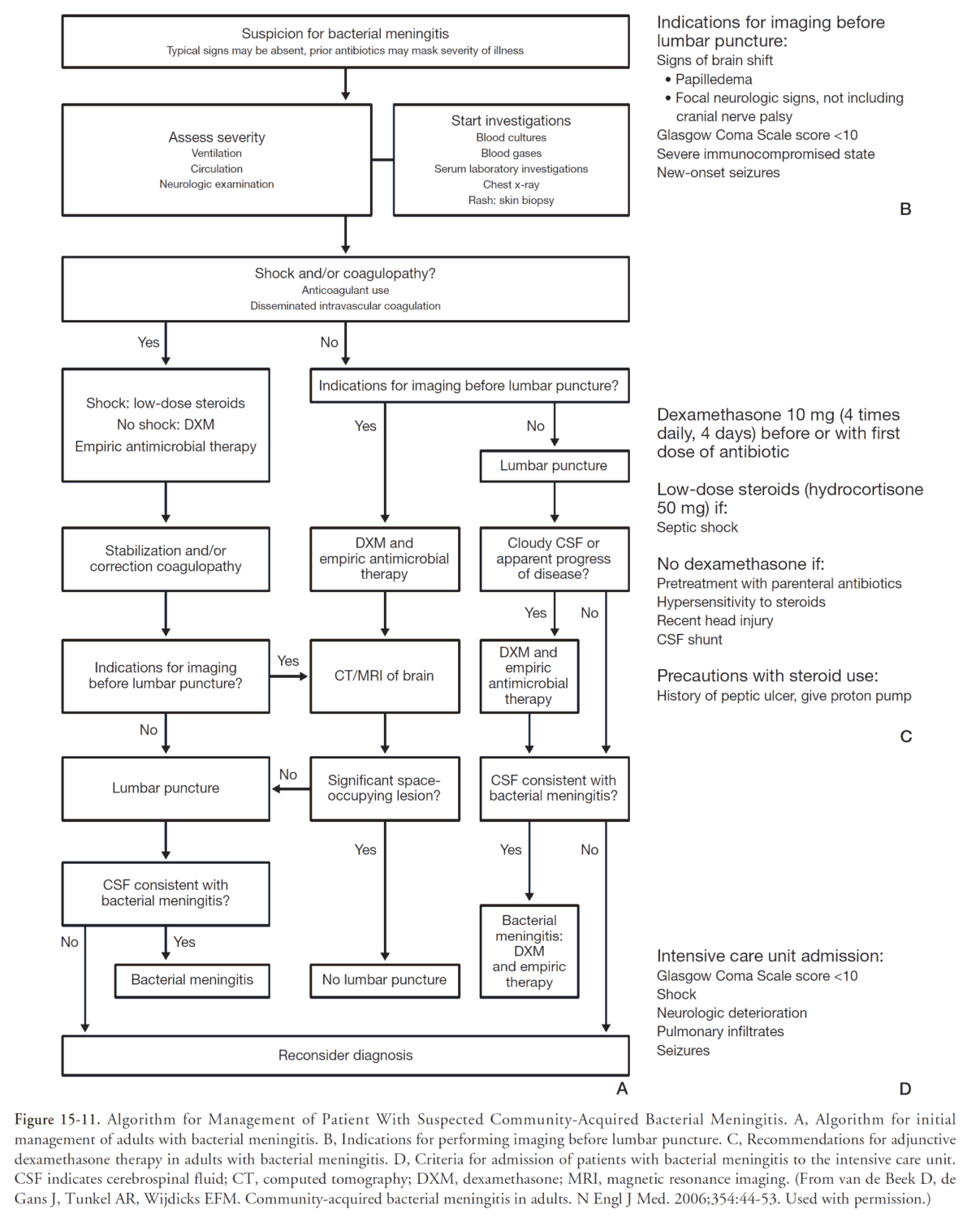

Computed Tomography (CT)

For most patients with meningitis, a computed tomography (CT) of the head is not required prior to the performance of an LP. Concerning patient characteristics and findings that should prompt a CT head prior to LP include:

- Immunosuppression

- History of central nervous system disease (i.e., mass lesion, stroke, focal infection)

- Focal abnormality on the neurologic examination

- New-onset seizure that occurs within 1 week of presentation

Treatment

In most cases, the clinical presentation and results of CSF analysis are sufficient to guide treatment and disposition.

For patients in whom there is clinical ambiguity, it is best to administer antimicrobial therapy while awaiting the results of CSF culture, as any delay in antibiotics in cases of confirmed meningitis is associated with a significant increase in mortality.

Importantly, antibiotic medications are given at higher doses when there is concern for meningitis.

- 2 g of ceftriaxone or 2 g of cefotaxime should be administered to immunocompetent patients under the age of 50 years to treat meningitis due to Streptococcal pneumoniae or Neisseria meningitides.

- Vancomycin should be administered in suspected cases of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcal aureus

- Ampicillin should be administered to patients with meningitis due to suspected Listeria monocytogenes.

In addition to antibiotic therapy, the administration of dexamethasone should be considered in cases of bacterial meningitis. Corticosteroids have been shown to reduce hearing loss and neurologic sequelae in patients with bacterial meningitis. Importantly, corticosteroids have not been shown to reduce patient mortality.

Key Points

- Do not exclude bacterial meningitis based on the absence of nuchal rigidity, Kernig sign, or Brudzinski sign.

- The presence of jolt accentuation increases the likelihood of meningitis in patients with fever and headache.

- Perform an LP to confirm the diagnosis of meningitis.

- Obtain a CT head prior to LP in immunosuppressed patients or those with a history of central nervous system disease, focal neurologic abnormality, or new-onset seizure that occurs within 1 week of presentation.

- Have a low threshold to administer antibiotics in patients with suspected meningitis.