This article is an answer to the Case – Patient with Pleuritic Chest Pain and Shortness of Breath

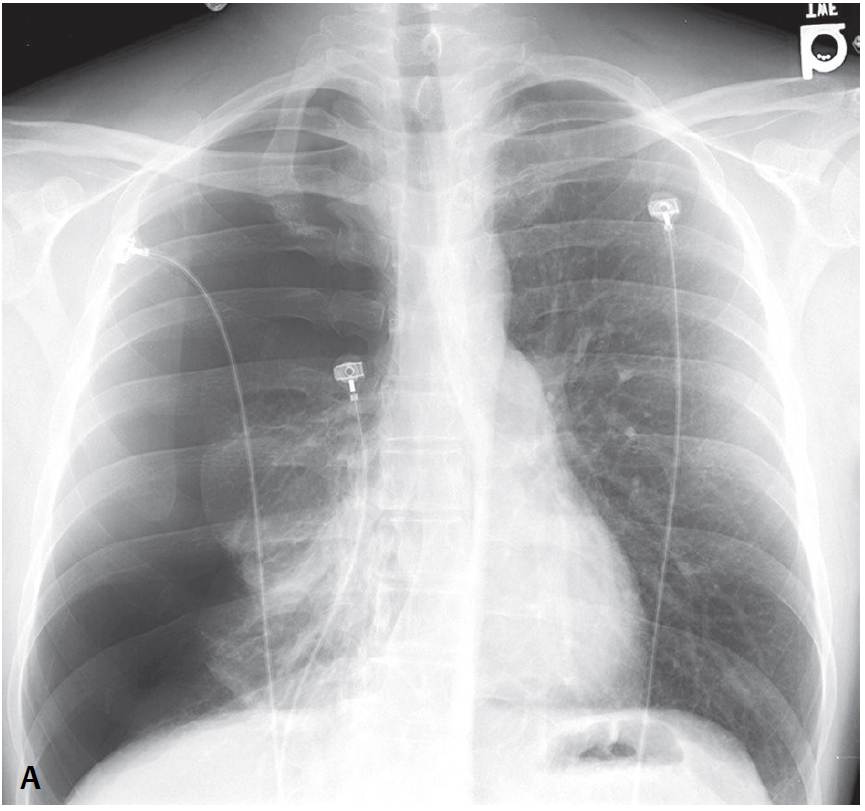

Radiologic Findings

Chest X-rays show a right-sided primary spontaneous pneumothorax with near total collapse of the right lung and contralateral mediastinal displacement.

Diagnosis

Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Differential Diagnosis

- Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

- Traumatic Pneumothorax

Etiology

Pneumothorax may be classified into one of three major categories:

- traumatic, which can be either iatrogenic (following unsuccessful central venous line or pacemaker-ICD placement, CT-guided or transbronchial biopsy, etc.) or non-iatrogenic (e.g., following blunt or penetrating chest injuries;

- primary spontaneous, caused by rupture of an air-containing space within (bleb) or immediately deep to the pleura (bulla); or

- secondary spontaneous, related to underlying lung disease (e.g., emphysema, chronic interstitial fibrosis or cystic lung disease).

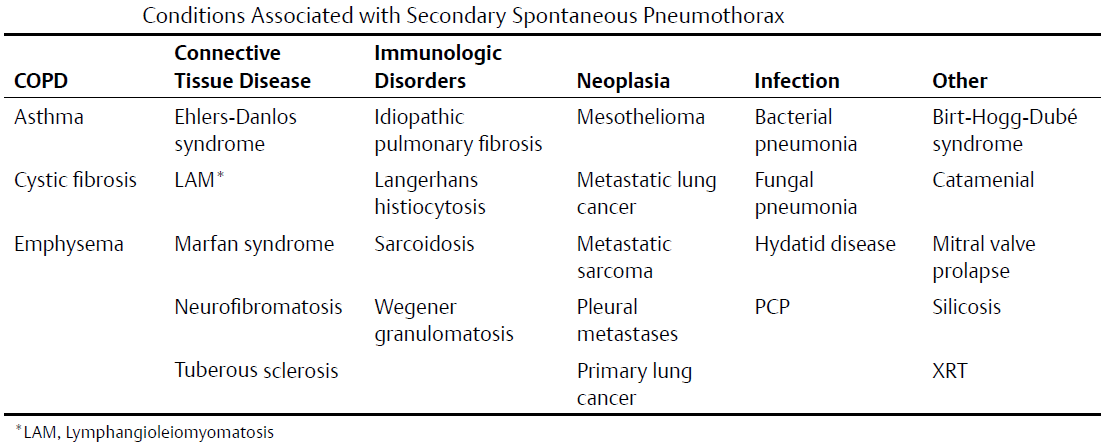

Pneumothorax may also develop from pneumomediastinum as a result of air tracking from the mediastinal pleura. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs most often in men (2–15M: 1F) in the third or fourth decade of life and shows a right-sided predilection and strong association with tobacco abuse. Numerous underlying conditions may be associated with secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (see table below), the most common of which is COPD. In some cases, the secondary spontaneous pneumothorax is the first clinical manifestation of the underlying disease.

Clinical Findings in Pneumothorax

Chest pain and/or dyspnea are the classic clinical symptoms of spontaneous pneumothorax. Breath sounds are decreased or absent on auscultation despite normal or increased resonance on percussion.

Imaging Findings

1. Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Chest Radiography

- Focal areas of apical emphysema or bulla typically not seen

- Visceral pleural reflection

- Vascular markings do not extend beyond lateral border

- Follows contour of the lung

- Radiographic density gradient proceeds from “gray” (aerated lung) to“white” (visceral pleural reflection) to “black” (pleural air)

MDCT

- Focal areas of apical emphysema or bullae identified (>80% of cases)

- Bullae located predominantly in the peripheral upper lobe or apices

- Localized low-attenuation areas ≥3 mm in diameter; ± thin walls

2. Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Chest Radiography

- Visceral-parietal pleural separation

- ± Evidence of underlying condition or predisposing disease (e.g., cystic lung disease, peripheral lung mass, interstitial fibrosis)

MDCT

- Mirrors conventional radiography findings, albeit more sensitive and specific

3. Pseudopneumothorax (skin fold, wrinkle in patient gown or sheet, external dressing)

Chest Radiography

- Typically “black” edge as opposed to “white” visceral pleural reflection, but not always

- May be linear, curvilinear, multiple; does not usually follow lung contour

- Vascular markings may or may not project beyond its lateral border

- Radiographic density gradient proceeds from “gray” (aerated lung) to “black” edge (pseudo-visceral pleural reflection) to “gray” (aerated lung)

Management of Pneumothorax

Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

- Decompression of affected pleural space

- Blebectomy, bullectomy, or pleurodesis

Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

- Decompression of affected pleural space

- Directed toward underlying condition or predisposing disease process

Prognosis

Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

- High recurrence rate in the absence of treatment: 30% ipsilateral; 10% contralateral

Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax

- Dependent on underlying condition

Pearls

- Most air-containing spaces associated with primary spontaneous pneumothorax are bullae.

- Major contributing factor to primary spontaneous pneumothorax is smoking, which increases the likelihood by 22 times in men and by 8 times in women.

- Focal areas of emphysema distend with decrease in atmospheric pressure (e.g., increasing altitude during air flight) and with rapid resurfacing after diving.

- Catamenial pneumothorax occurs at the time of menstruation and may be recurrent with the woman’s menstrual cycle. Postulated mechanisms include endometrial pleural and diaphragmatic implants (20– 60% of patients have pelvic endometriosis) and migration of air from vagina, uterus, and fallopian tubes into peritoneal cavity, across diaphragmatic pores and defects into pleural space.

Suggested Reading

- Alifano M. Catamenial pneumothorax. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2010;16(4):381–386

- Fraser RS, Müller NL, Colman N, Paré PD. Pneumothorax. In: Fraser and Paré’s Diagnosis of Disease of the Chest, 4th ed. New York: WB Saunders Company; 1999:2781–2794

- Noppen M, De Keukeleire T. Pneumothorax. Respiration 2008;76(2):121–127

- Wakai A. Spontaneous pneumothorax. Clin Evidence (online) 2008; Mar 10:1505