Table of Contents

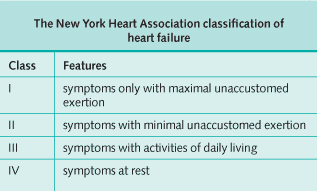

Heart failure occurs when the heart is unable to maintain sufficient cardiac output to meet the demands of the body, despite the presence of normal filling pressures. The incidence rises with age and is present in over 1% of the over-65s. It is classified by its severity (see table below). The mortality in severe heart failure is about 50% at 1 year.

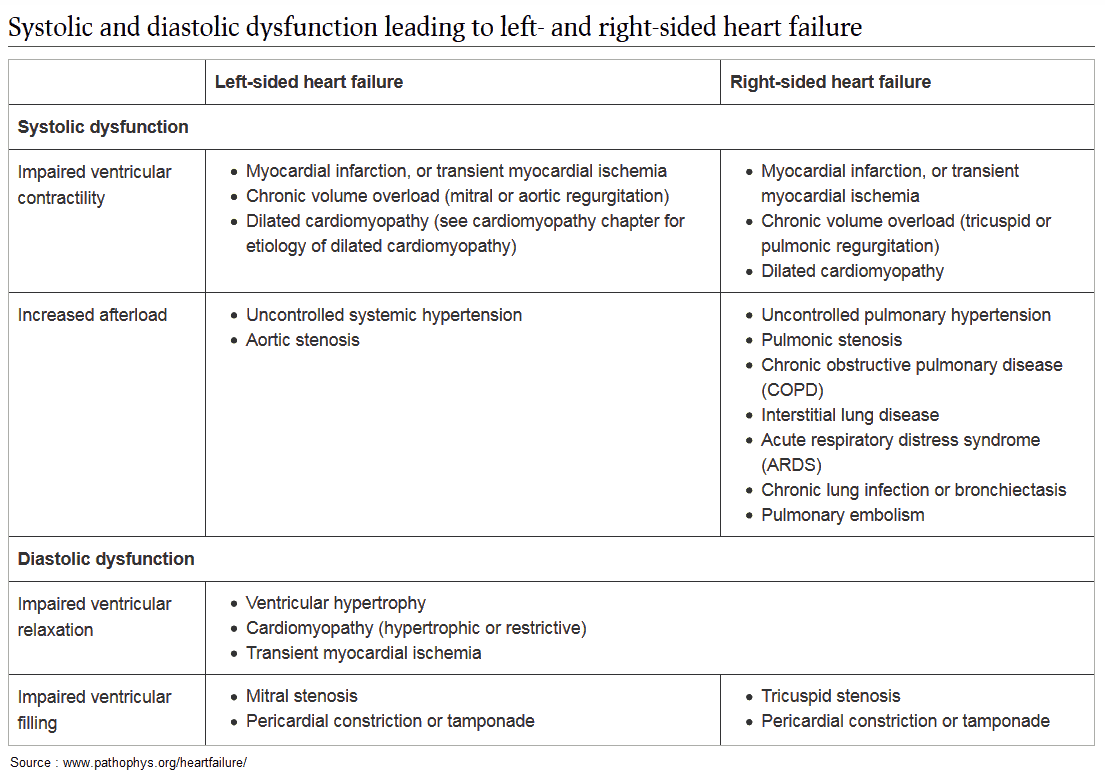

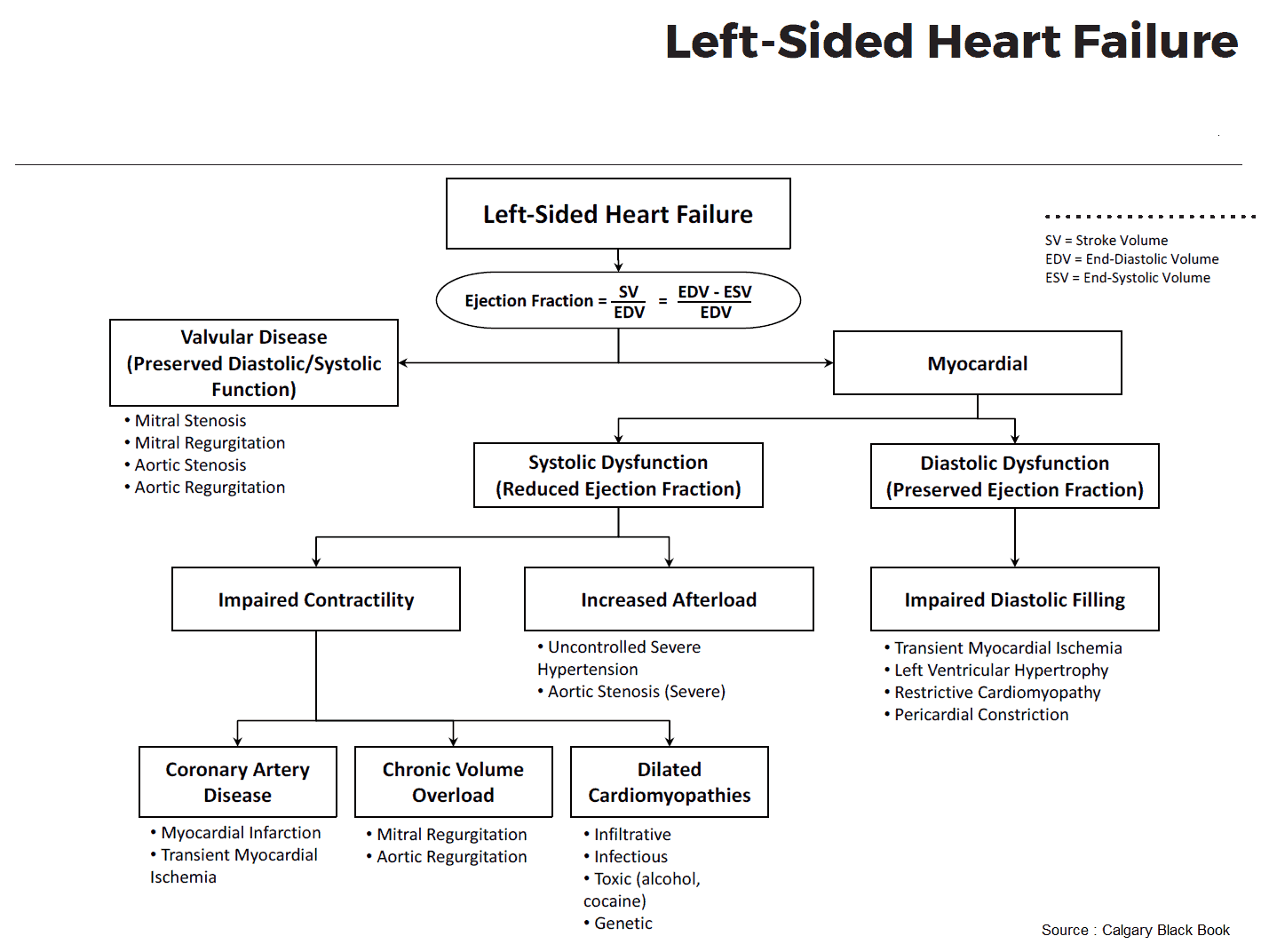

Causes of Heart Failure

1. High output failure

The heart maintains a normal or increased cardiac output in the face of grossly elevated requirements. It is then unable to meet these requirements. Conditions causing this include:

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Nephritis

- Anemia

- AV shunts

- Beriberi

- Fever

- Paget’s disease

- Pregnancy

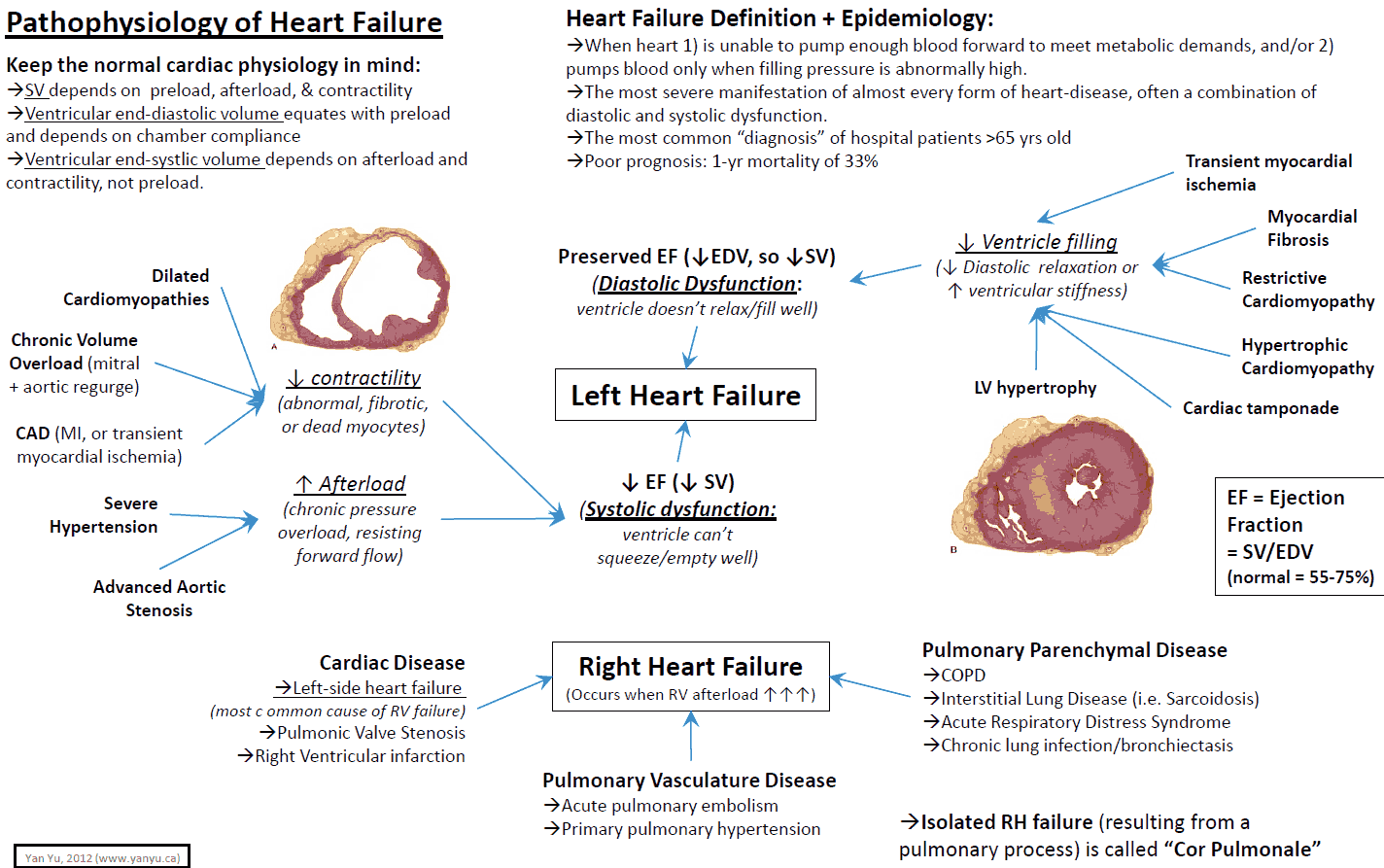

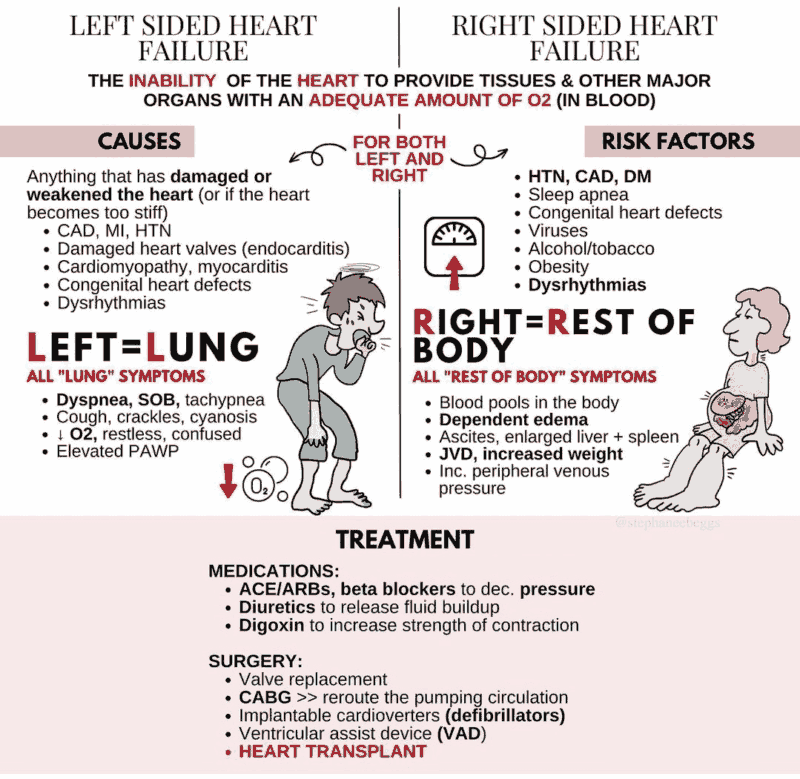

2. True Heart Failure

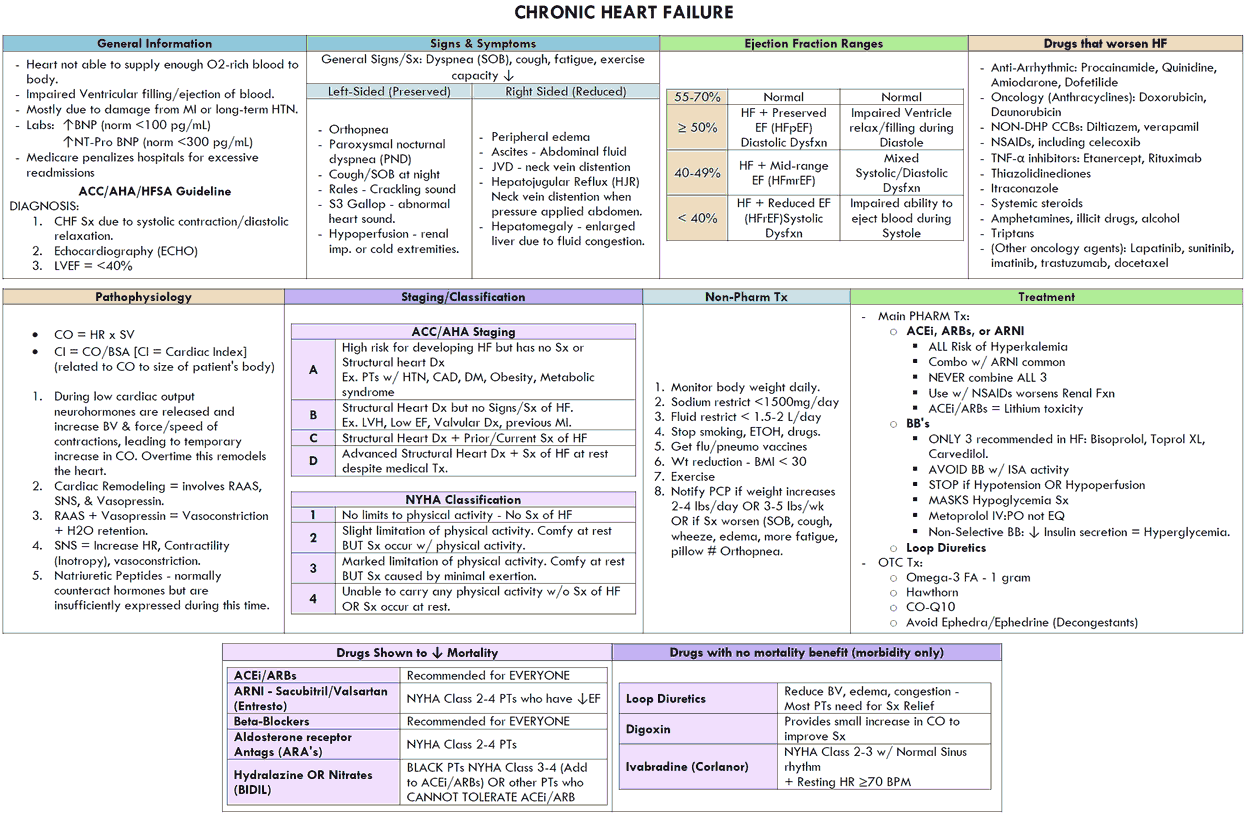

True heart failure is due primarily to an abnormality of the heart, when the cardiac output at rest is low or normal, but low on exercise. Causes include the following:

- Myocardial disease: ischemia and infarction; structure (e.g., hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, hypertension); fibrosis (e.g., infections, immunologic reactions, small vessel disease); others (e.g., thyroid disease, beriberi, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, heavy metals, alcohol)

- Drugs (e.g., antiarrhythmics, calcium antagonists, β-blockers)

- Arrhythmias (e.g., atrial fibrillation)

- Volume overload (e.g., aortic and mitral regurgitation)

- Outflow obstruction (e.g., aortic stenosis)

- Restricted filling (e.g., constrictive pericarditis or tamponade, restrictive cardiomyopathy)

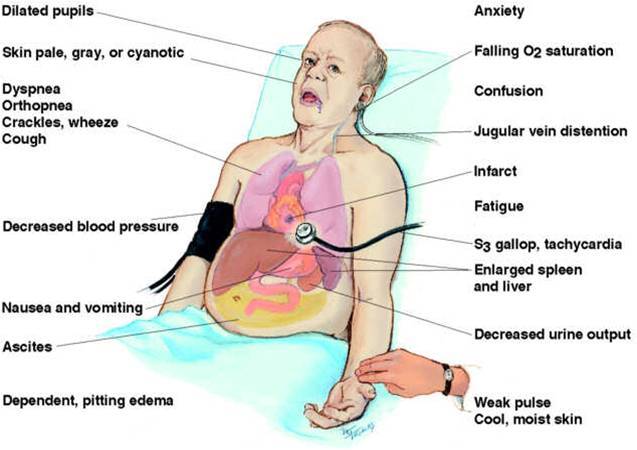

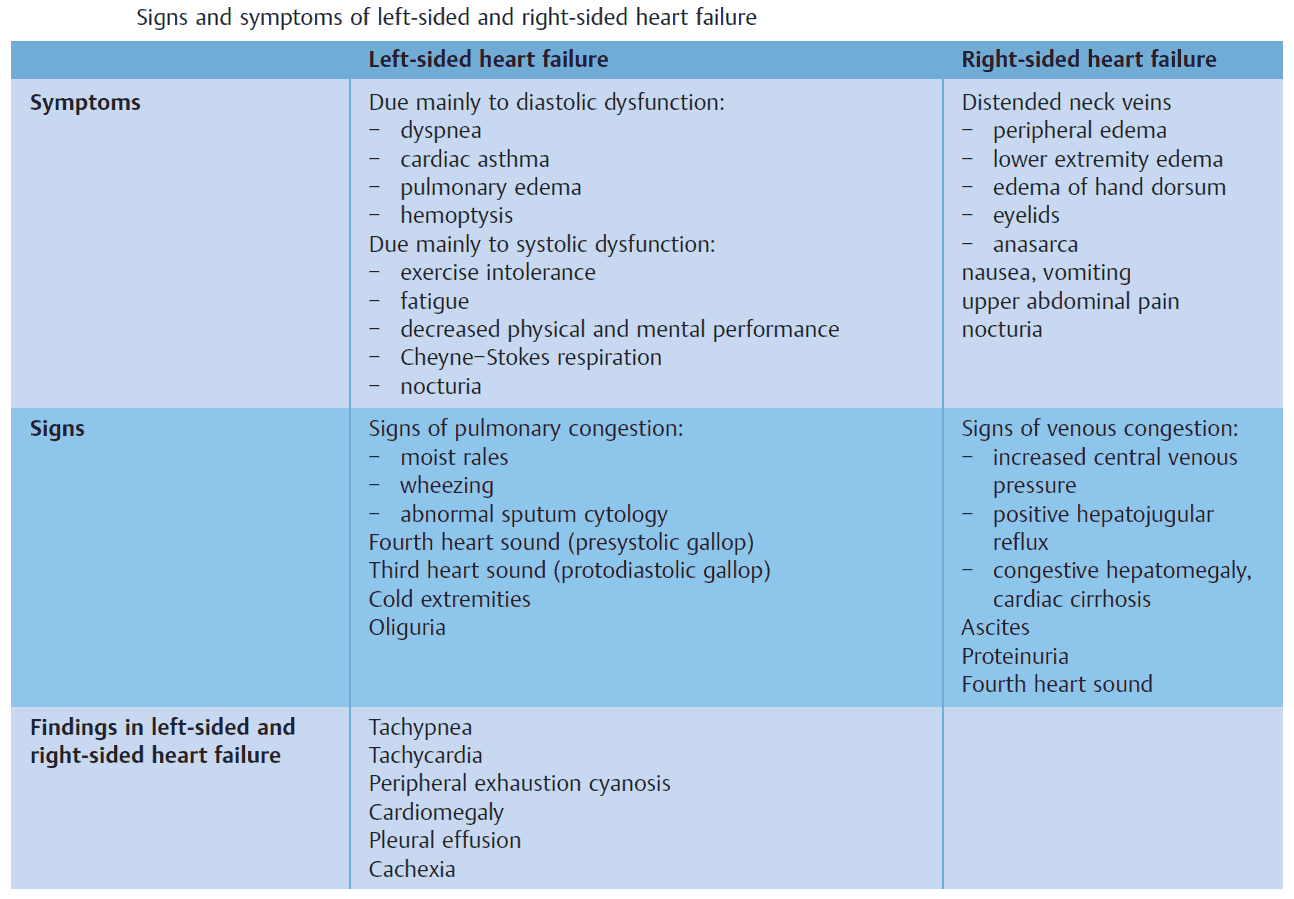

Clinical Features of Heart Failure

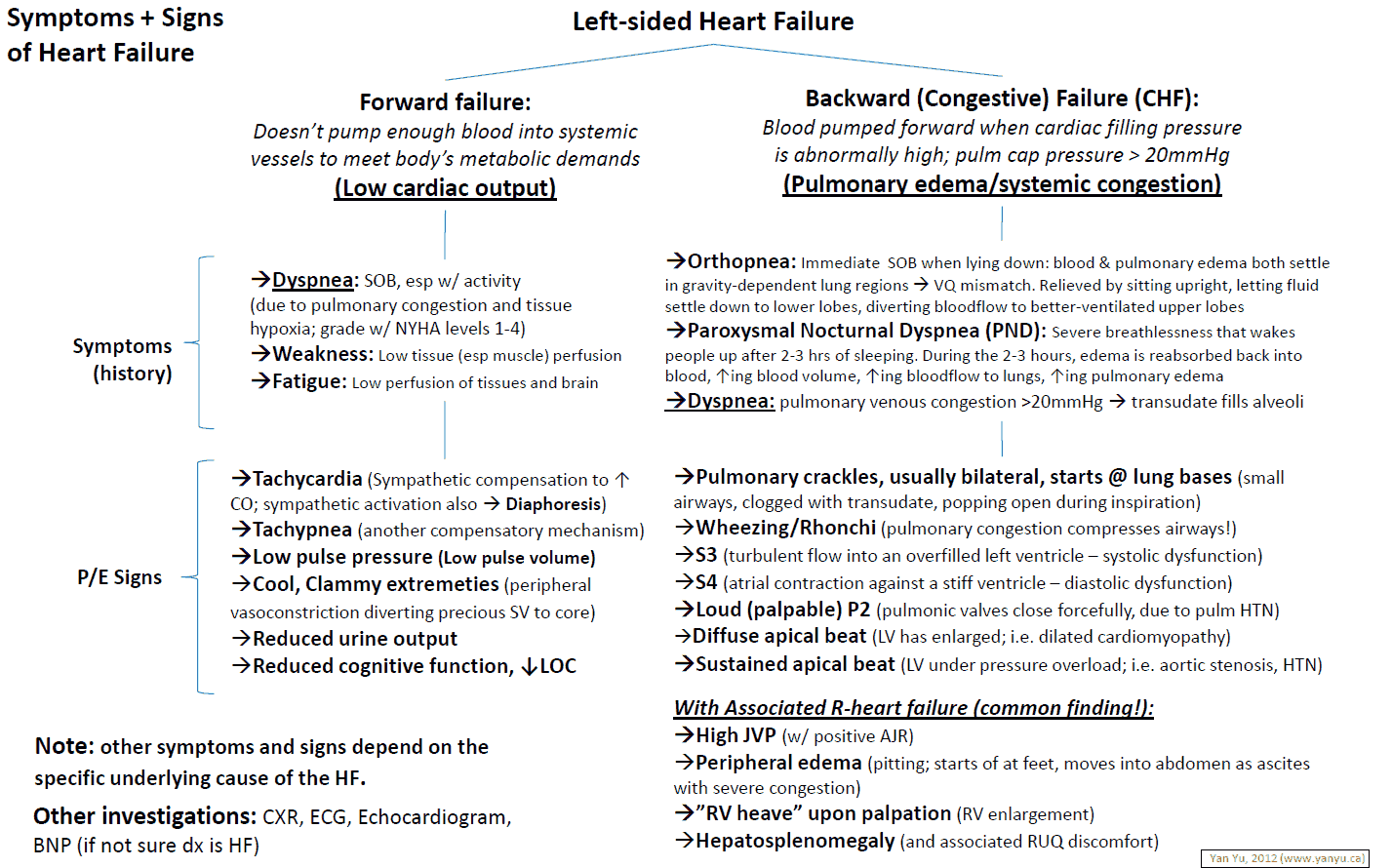

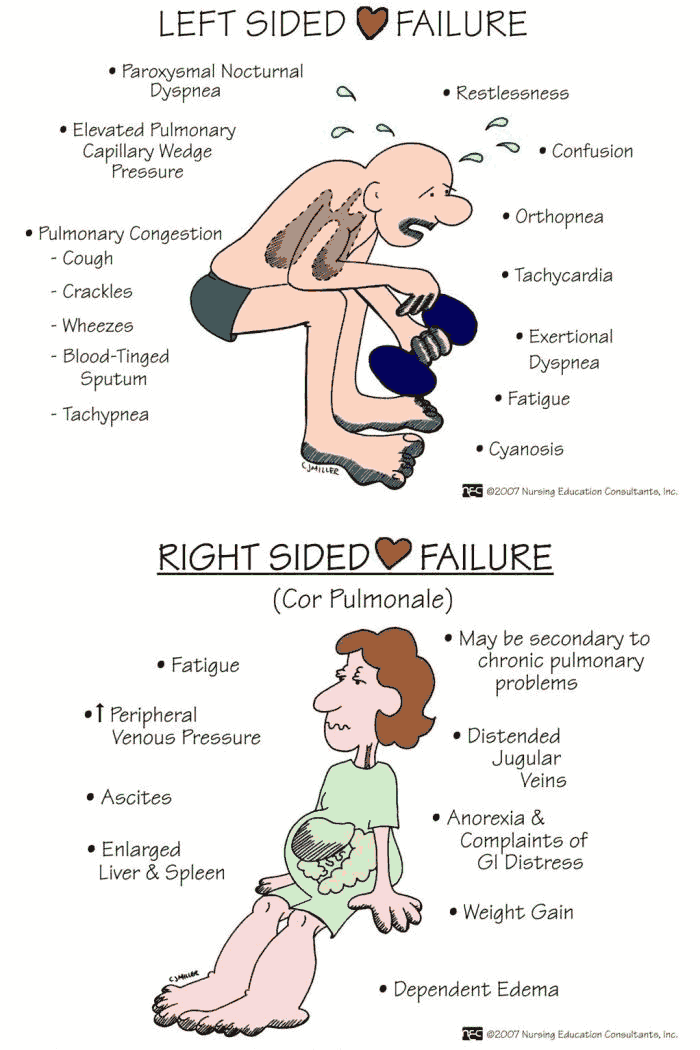

Clinical Features of Left heart failure

Symptoms include:

- Exertional dyspnea

- Orthopnea

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- Fatigue

- Wheeze

- Cough

- Hemoptysis

Signs include:

- Tachypnea

- Tachycardia

- Pulsus alternans (alternating large and small pulse pressures)

- Peripheral cyanosis

- Cardiomegaly

- A third heart sound

- Functional mitral regurgitation secondary to dilatation of the mitral annulus

- Basal crepitations

- Pleural effusions

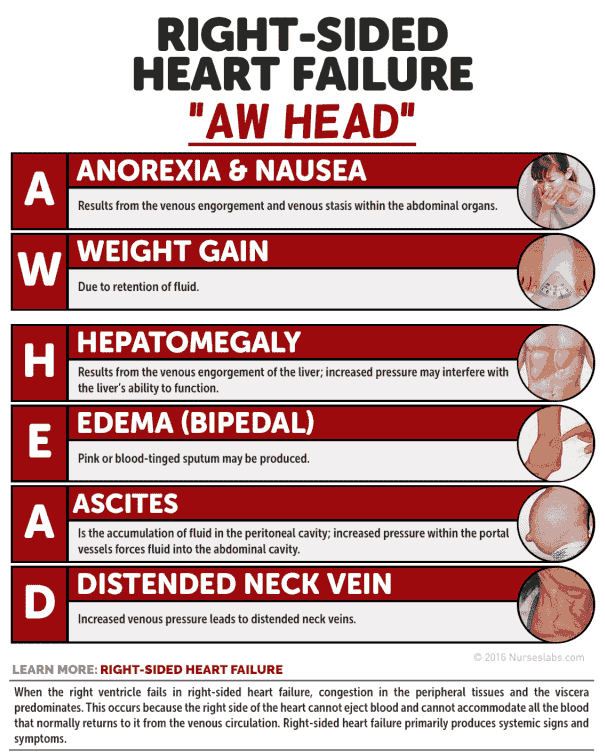

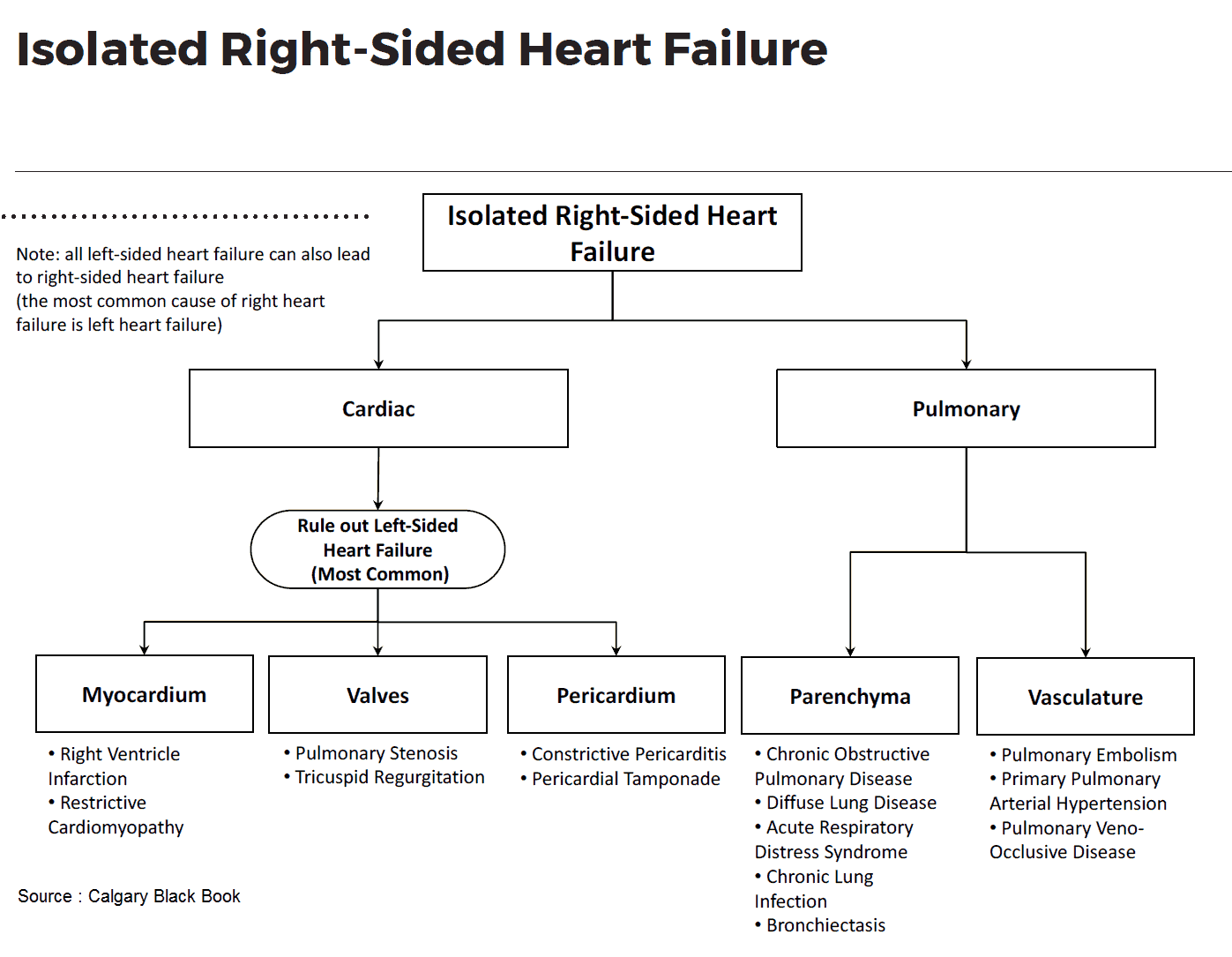

Clinical Features of Right heart failure

This may occur secondary to chronic lung disease, multiple pulmonary emboli, pulmonary hypertension, right-sided valve disease, left-to-right shunts, or isolated right ventricular cardiomyopathy. It is most commonly secondary to LVF, in which case the term congestive heart failure is used.

Symptoms include:

- Fatigue

- Nausea

- Wasting

- Swollen ankles

- Abdominal discomfort

- Anorexia

- Breathlessness

The signs include:

- A raised jugulovenous pressure (JVP)

- Smooth hepatomegaly

- Liver tenderness

- Pitting edema

- Ascites

- Functional tricuspid regurgitation

- Tachycardia

- Right ventricular third heart sound

Investigations in Heart Failure

The cause for the heart failure must always be sought as heart failure itself is an inadequate diagnosis. After the history and examination, investigations include the following:

- CBC: anemia.

- Metabolic panel (e.g., for hypokalemia with diuretics).

- LFTs: liver congestion.

- Echocardiography: left ventricular function and valves.

- TFTs.

- Cardiac enzymes: if acute onset, to exclude MI.

- ECG: CAD, arrhythmias, and left ventricular hypertrophy.

- CXR: cardiomegaly, alveolar edema, bat’s wings shadowing, prominent upper lobe vessels, Kerley B lines, pleural effusions.

Other investigations to consider are:

- Exercise testing: functional severity and prognosis.

- Cardiac catheterization.

- Nuclear techniques: ejection fraction, cardiac function, prognosis.

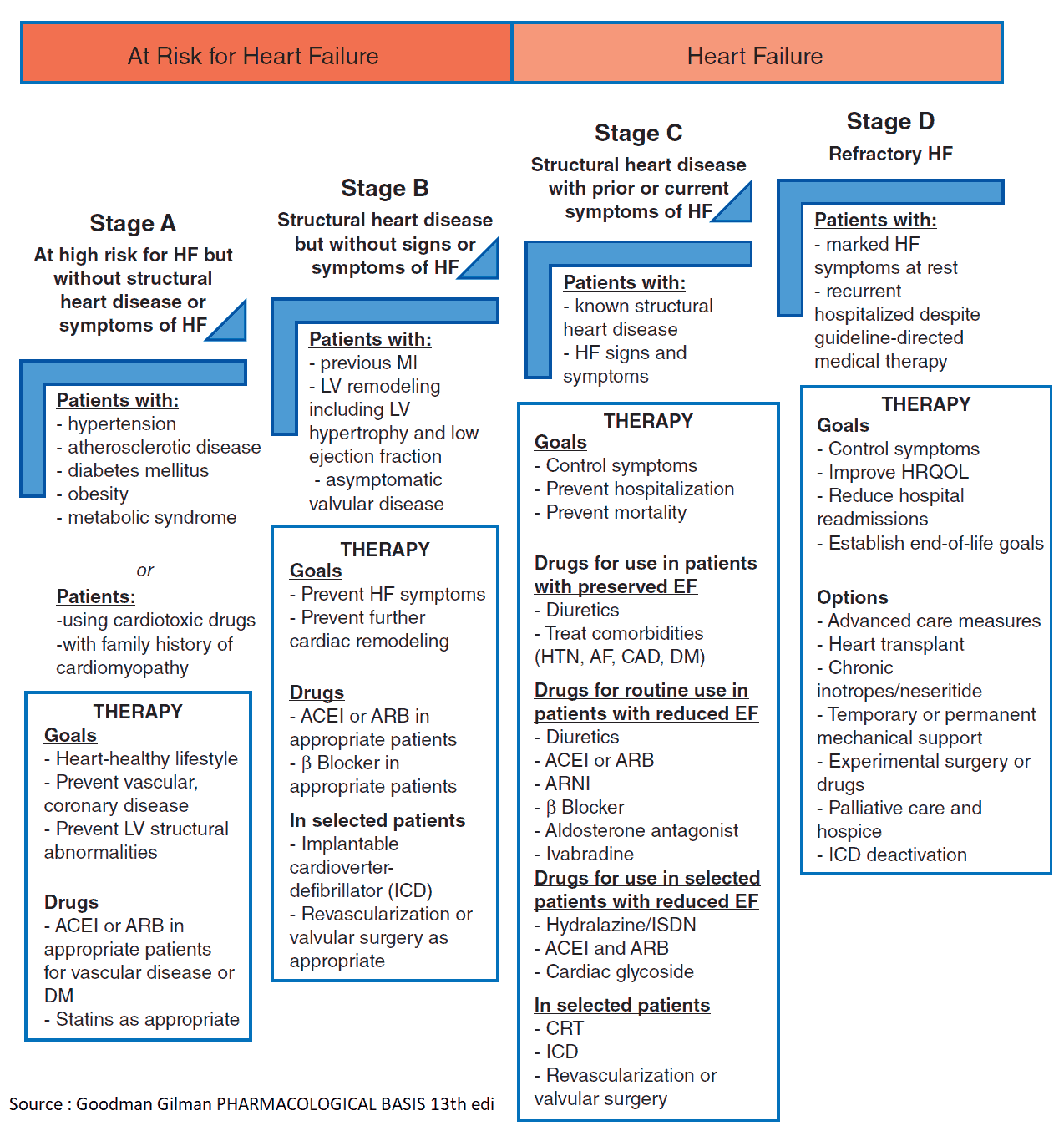

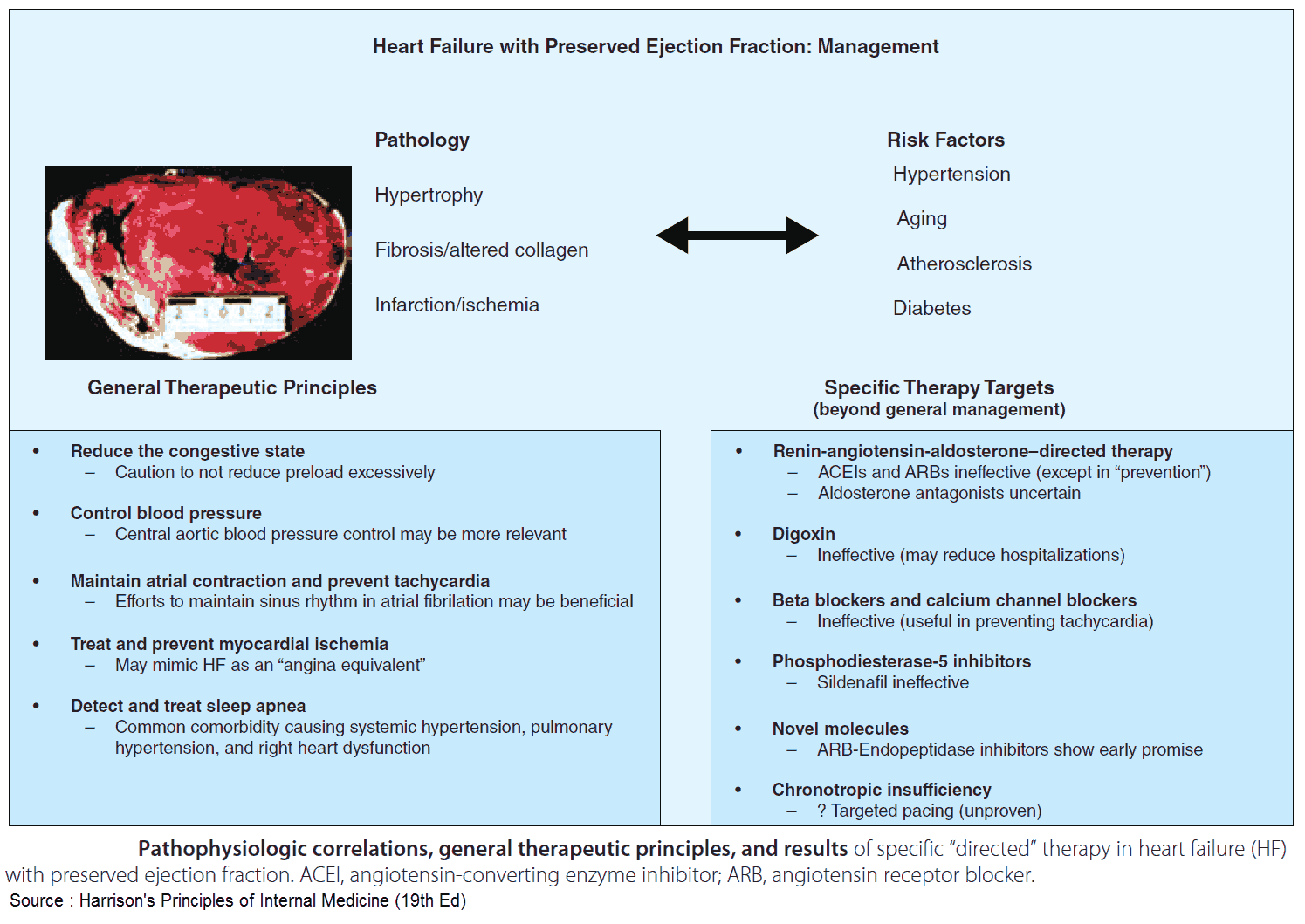

Management of Heart Failure

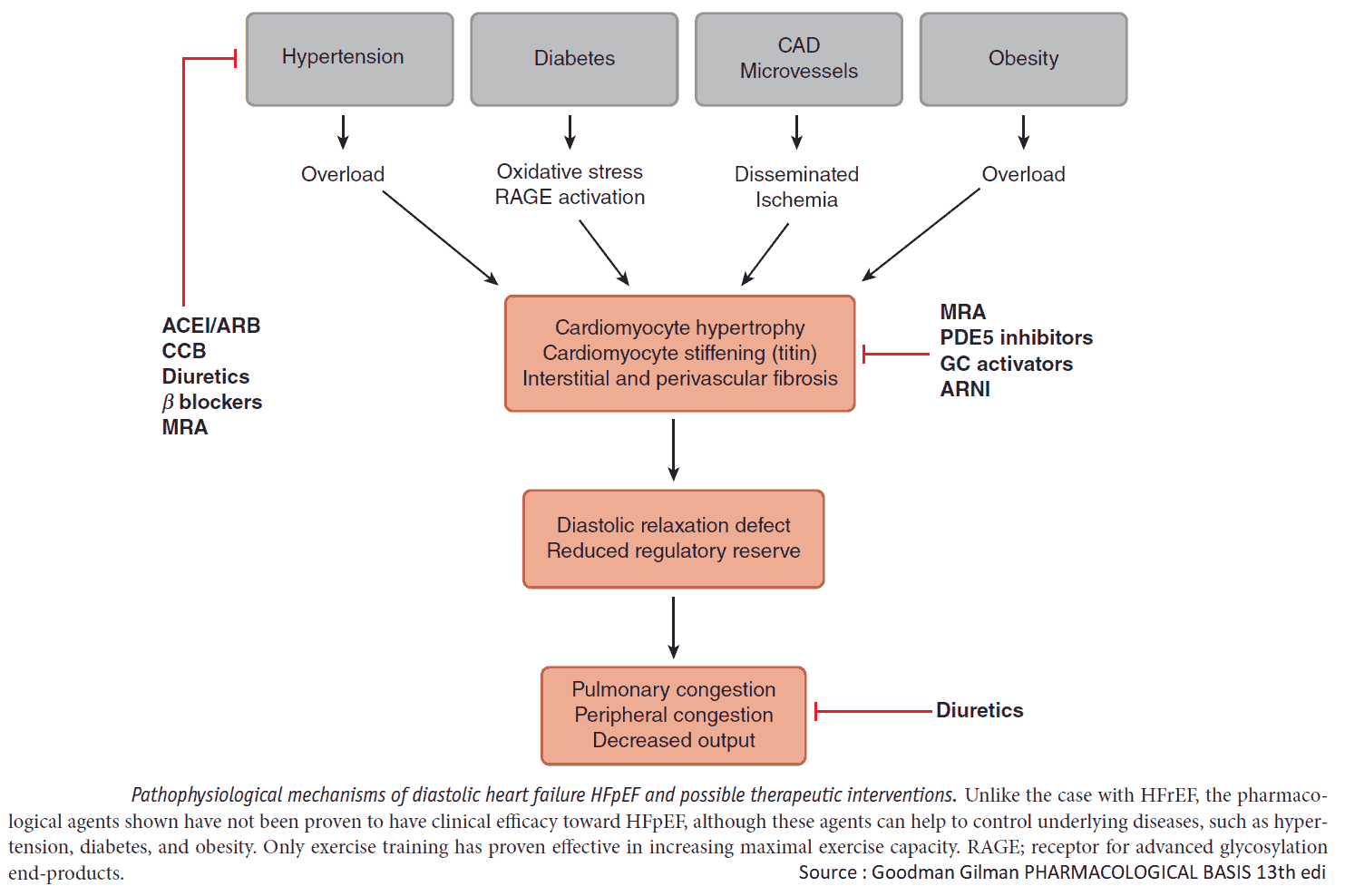

The aims of management are to relieve symptoms and to improve the prognosis. The cause of the heart failure should be sought and treated appropriately (e.g., valve lesions). Exacerbating factors such as anemia and hypertension should be treated. Check the patient’s drugs as some may cause fluid retention (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]). Patients should be advised to maintain an optimal weight, avoid excessive salt intake and large amounts of alcohol, and stop smoking.

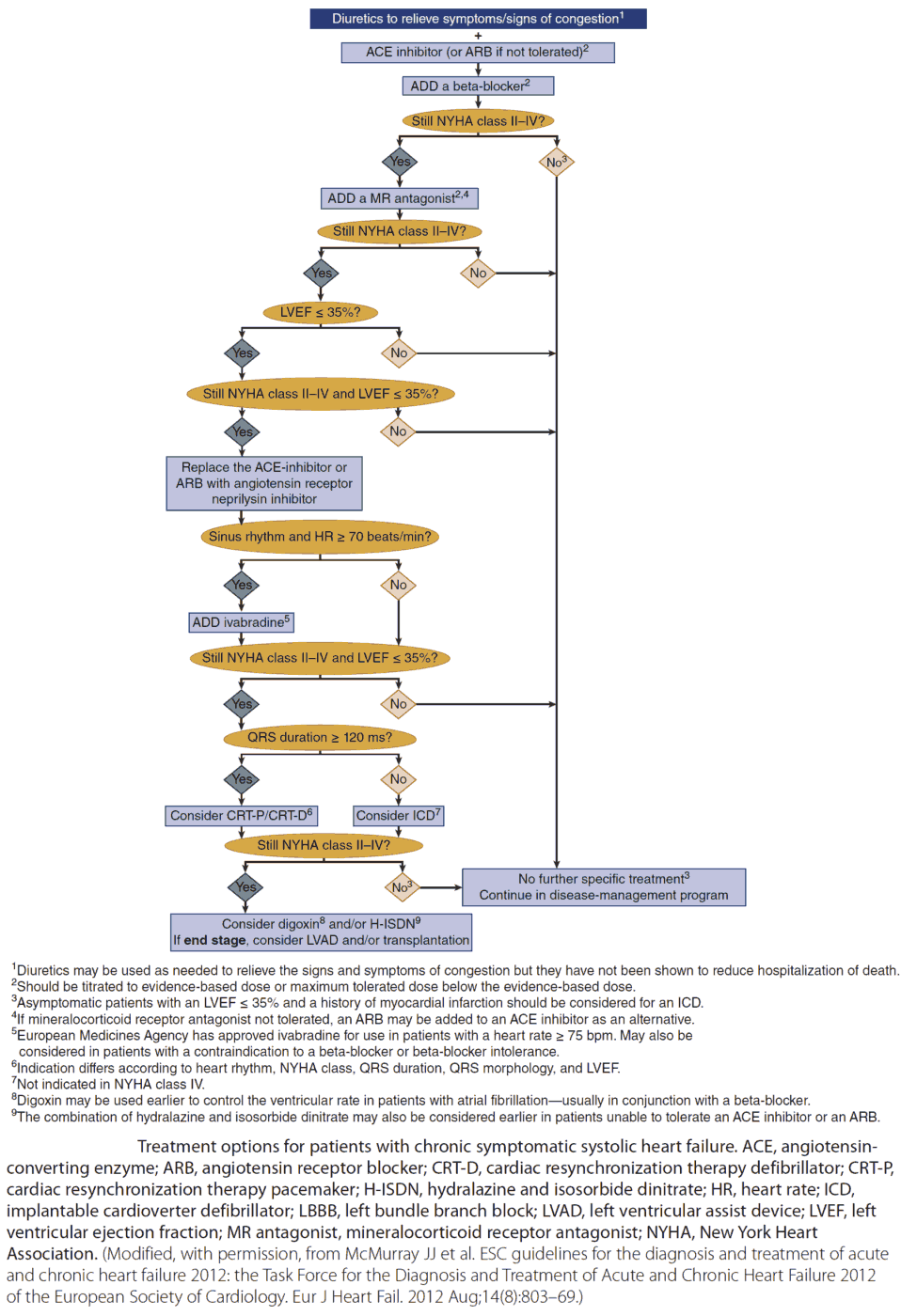

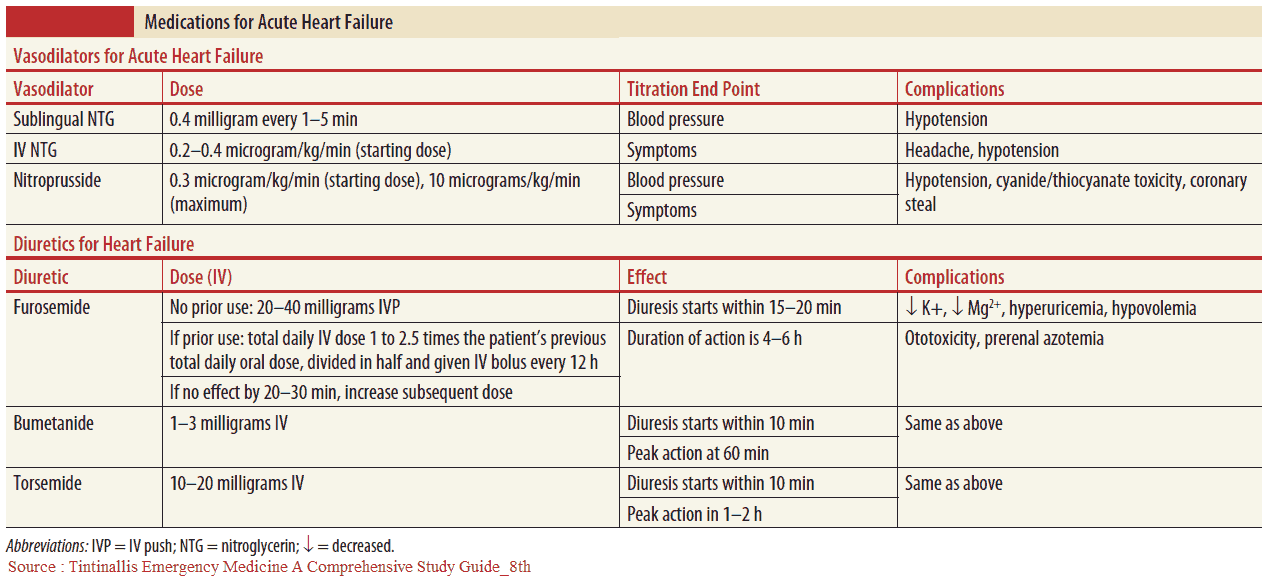

Drug Treatment

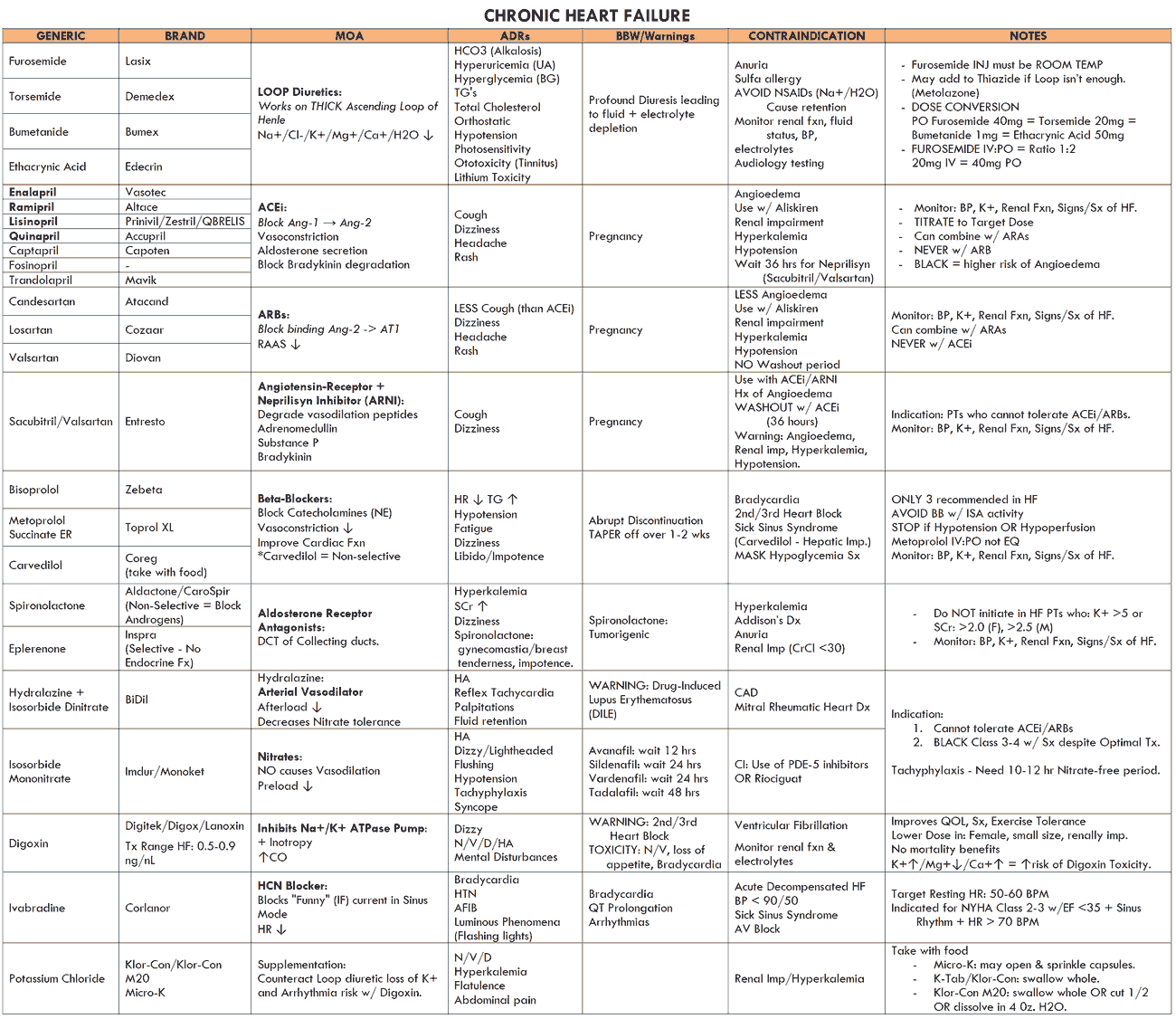

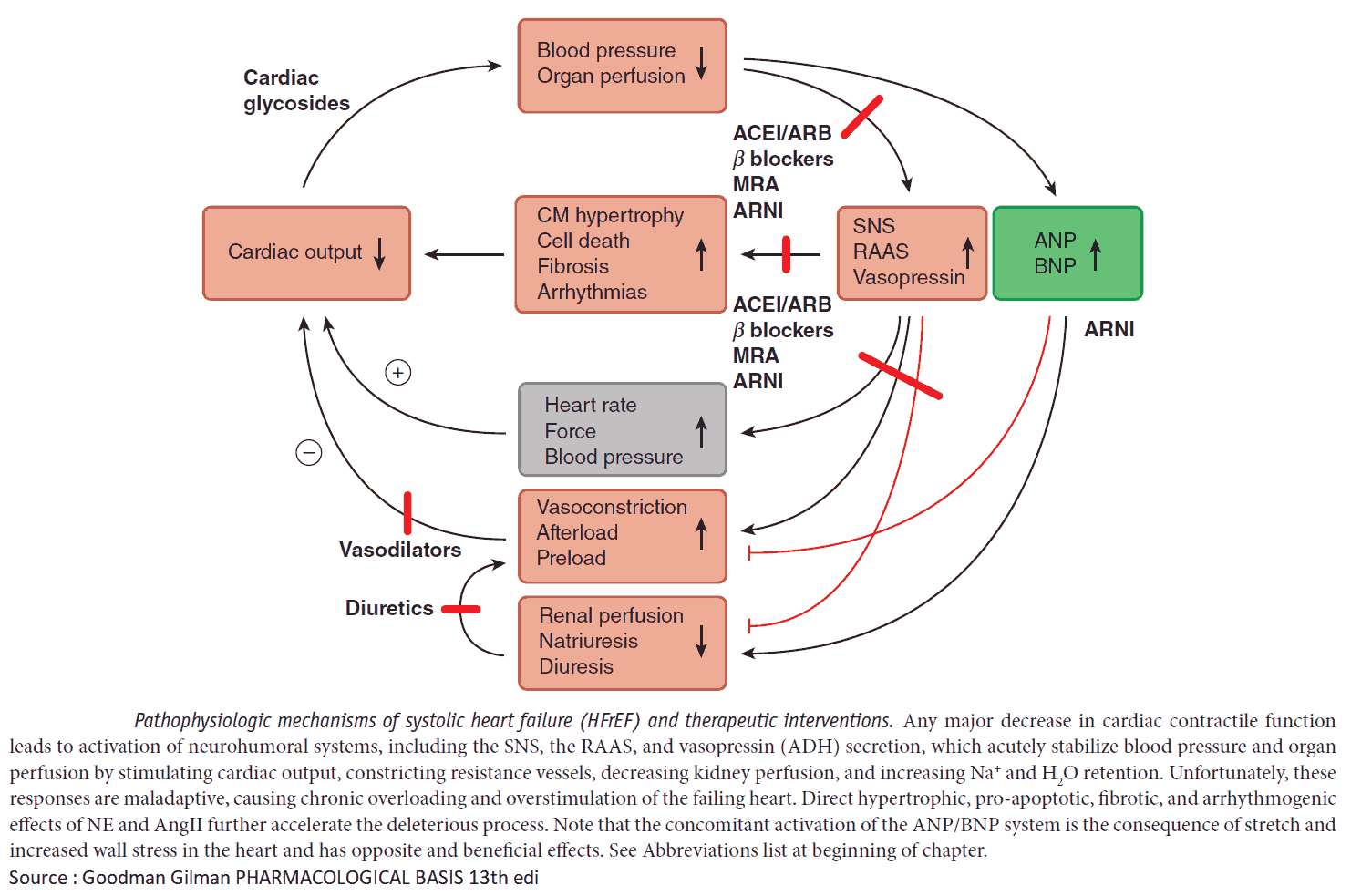

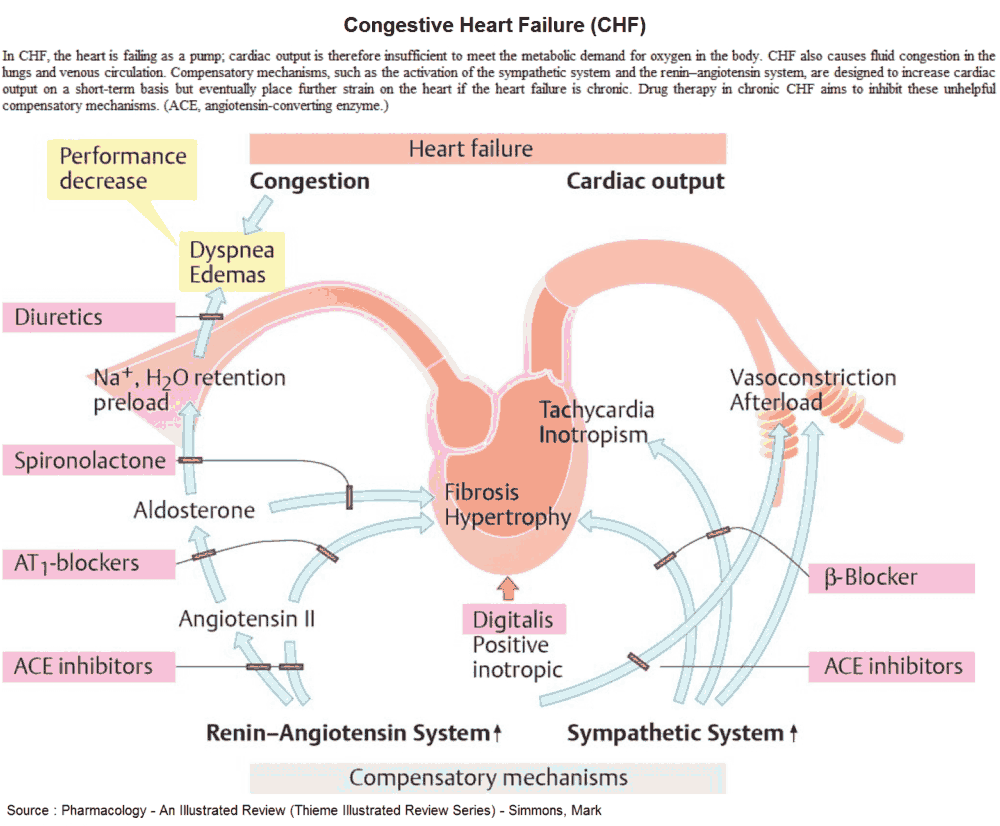

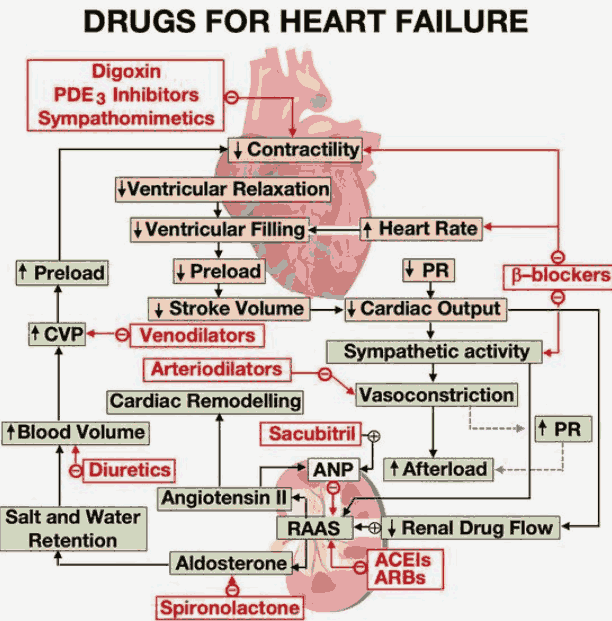

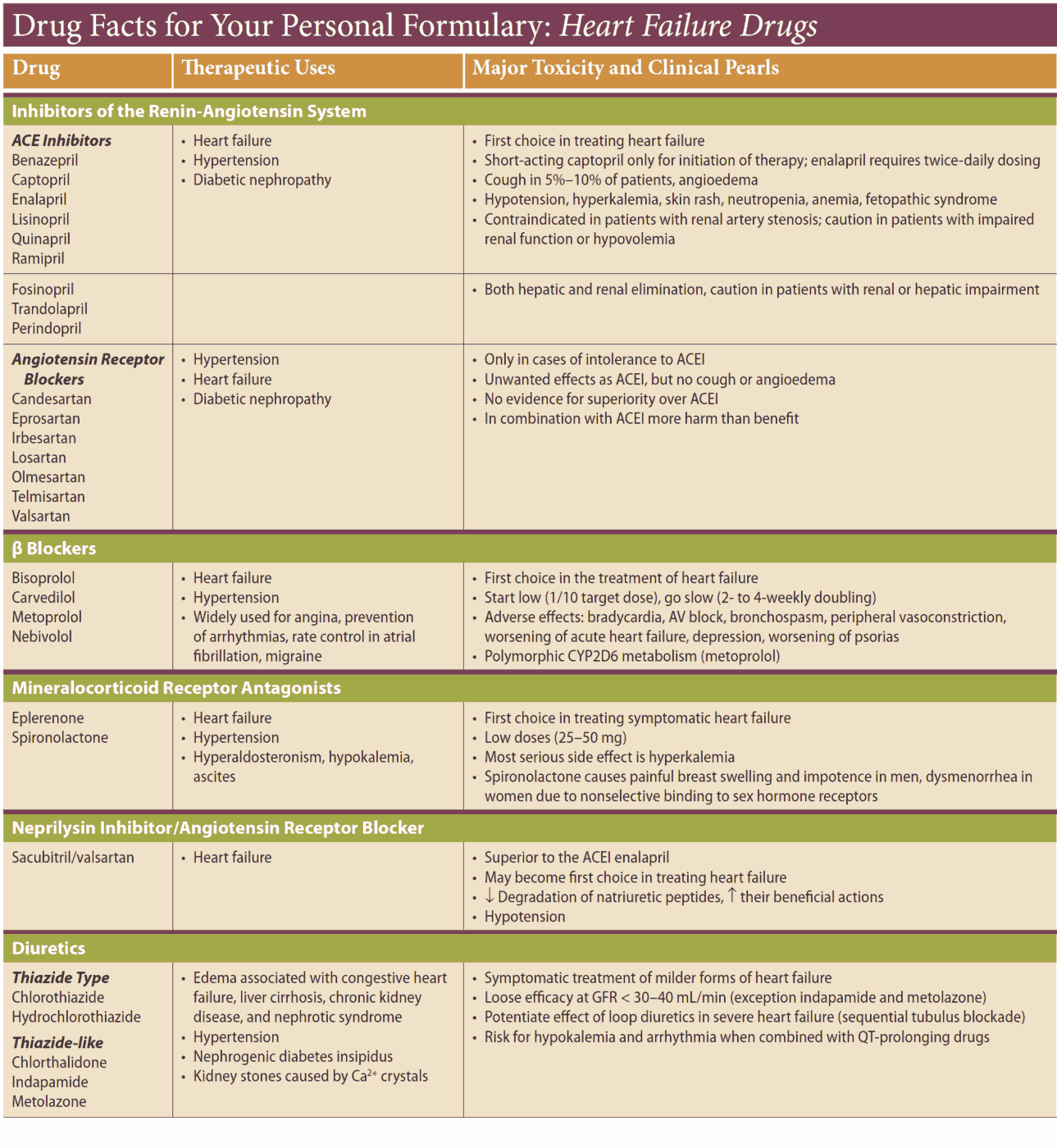

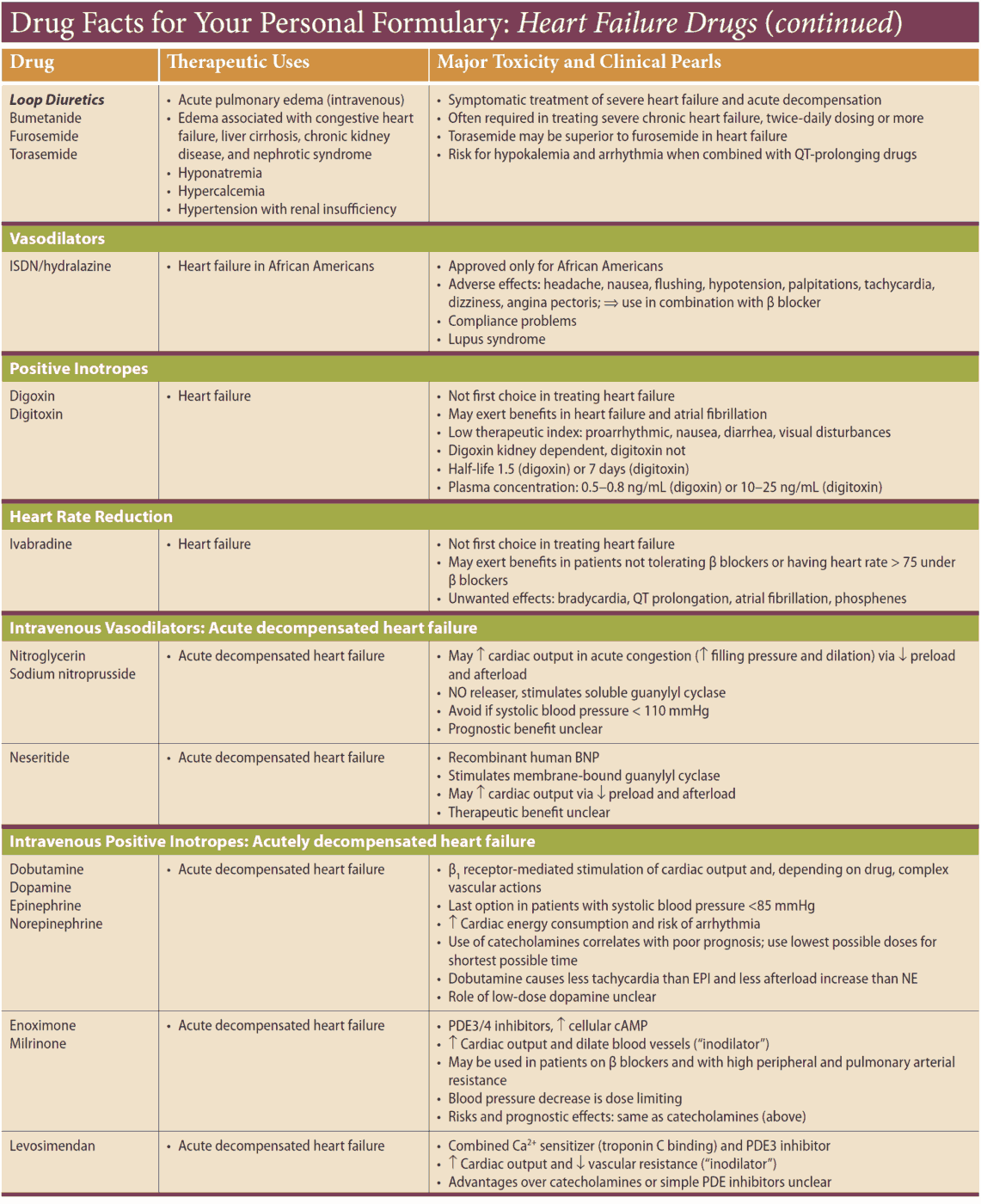

Diuretics relieve the symptoms of heart failure, and ACE inhibitors improve symptoms and prognosis. They reduce the risk of MI and increase survival. Treatment is best planned as a stepped care plan.

Step 1

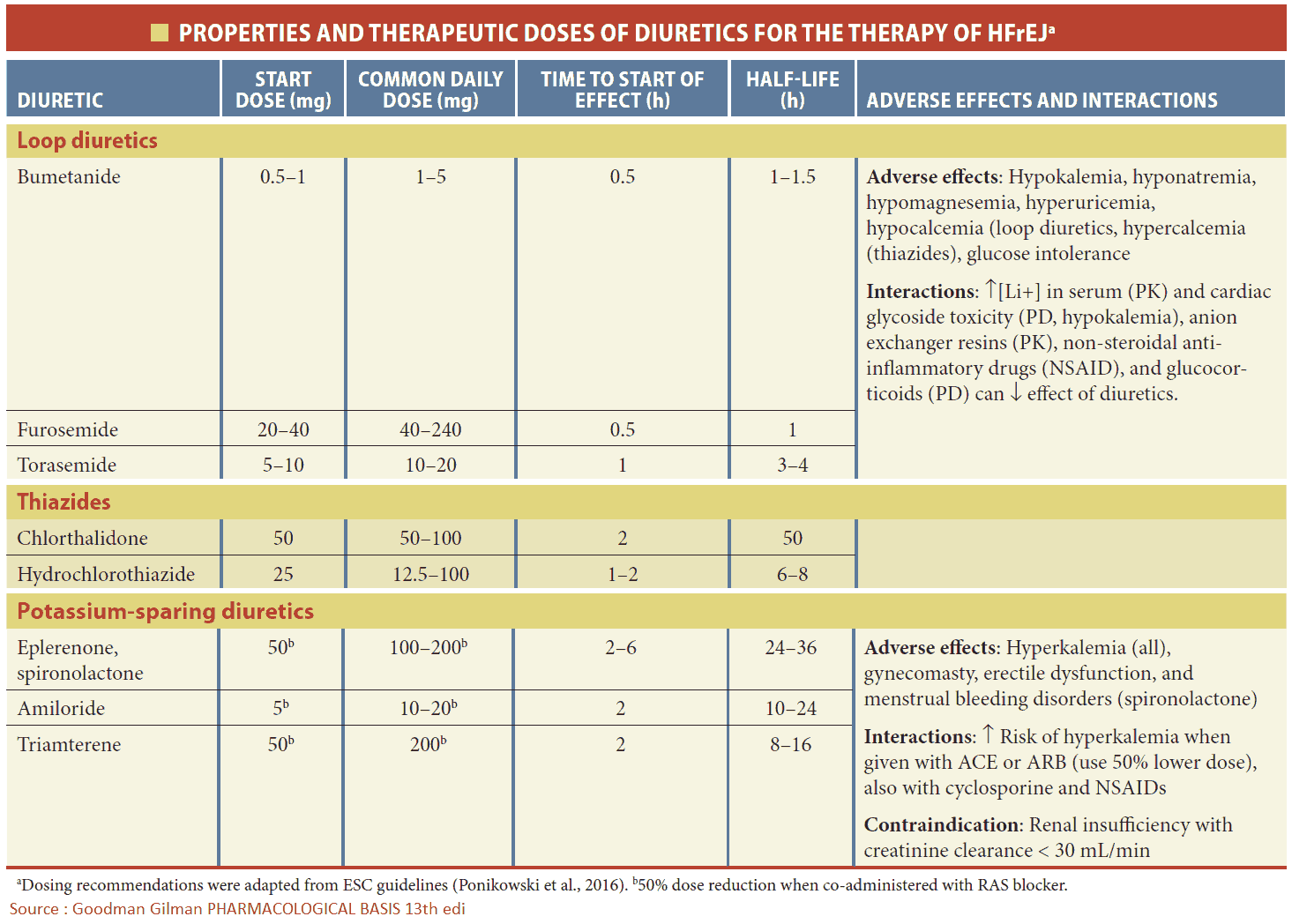

If the heart failure is mild, start a thiazide diuretic (e.g., HCTZ 2.5 mg q.d.). Many patients are started on a loop diuretic from the outset (e.g., furuosemide 20-40 mg daily). Diuretics increase the excretion of sodium and water, and, by reducing the circulatory volume, they decrease the preload and edema.

Loop diuretics have a thiazide-like action on the early distal tubule but more importantly they inhibit sodium and chloride reabsorption in the thick ascending loop of Henle. This segment has a high capacity for absorbing sodium and chloride, and so drugs which act on this site produce a diuresis that is much greater than that of other diuretics. Side effects include hyperglycemia, hyperuricemia, hypotension, and hypokalemia.

Step 2

An ACE inhibitor should be commenced at the same time if there are no contraindications. The dose should be increased to the maximum tolerated dose (see table below).

As the name suggests, ACE inhibitors inhibit the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II. To avoid dangerous hyperkalemia, any potassium-sparing diuretic should be omitted from the diuretic regimen before introducing an ACE inhibitor, changing to the loop diuretic alone. Potassium supplements should be discontinued.

Profound first-dose hypotension may occur when ACE inhibitors are introduced to patients with heart failure who are already on a high dose of a loop diuretic (e.g., furosemide 80 mg q.d. or higher). Temporary withdrawal of the loop diuretic reduces the risk but may cause severe rebound pulmonary edema. The ACE inhibitor should therefore be started at a very low dosage with the patient recumbent and under close medical supervision, and with facilities to treat profound hypotension.

Alternative step 2

The contributions of venodilators such as long-acting nitroglycerine, which will reduce preload, and arterial dilators such as hydralazine, which will reduce afterload, have been shown to be of prognostic benefit in people with heart failure but are inferior to ACE inhibitors in this respect. They may be prescribed to patients in whom ACE inhibitors are contraindicated. The combination of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate has been found to be beneficial in black patients.

Aldosterone receptor blockade with spironolactone (25 mg orally once daily) has been shown to improve mortality rates in class III-IV CHF. Renal function and serum potassium should be monitored carefully after initiating treatment with spironolactone.

Step 3

This next stage is to increase the dose of loop diuretic. For patients with intractable heart failure, very high doses of furosemide may be needed-up to 1 g per day.

Step 4

The addition of digoxin for its inotropic effect has been shown to reduce hospital admissions and symptoms, although not mortality. It is of particular benefit in patients with atrial fibrillation. It should be used with caution in the elderly, who are particularly susceptible to digoxin toxicity.

Common toxic effects are anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. Digoxin may also cause almost any supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmia and heart block. These unwanted effects depend both on the plasma digoxin concentration and on the sensitivity of the conducting system or myocardium, which is often increased in heart disease.

Hypokalemia predisposes to toxicity, and serum potassium should be monitored. Renal function is the most important determinant of digoxin dosage. Typical maintenance doses are 125-250 mg daily although lower doses may be needed if there is renal impairment. Toxicity can often be managed by discontinuing therapy and correcting hypokalemia if appropriate. Digoxin-specific antibody fragments are available for the reversal of life-threatening overdosage.

Step 5

Traditionally, beta blockers are contraindicated in patients with heart failure because of their negative inotropic effect. However, carvedilol, which is a beta blocker with additional arteriolar vasodilating action, may be of benefit if heart failure is severe.

Step 6

If heart failure is intractable, the addition of metolazone, a powerful thiazide diuretic, produces a profound diuresis, acting synergistically with loop diuretics.

Angiotensin II antagonists are being increasingly used in patients with heart failure. They should be considered if there are contraindications to ACE inhibitors.

Other drug options

Other drug options to consider are phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as enoximone and milrinone, which increase myocardial contraction and are vasodilators. Sustained hemodynamic benefit has been shown after administration but as yet there is no conclusive evidence of any beneficial effect on survival.

Bed rest may promote diuresis. Prophylaxis for DVT should be given with subcutaneous heparin. It may sometimes help giving furosemide intravenously, either as a slow bolus or continuous intravenous infusion.

As a last resort, β-adrenergic agonists, dopamine and dobutamine produce a positive inotropic effect but must be given intravenously. They may be useful for acute exacerbations of heart failure but may induce inotrope dependence, making it difficult to wean the patient off them.

For patients with severe heart failure, heart transplantation should be considered. This can dramatically improve the quality of life; 5-year survival is over 70%.

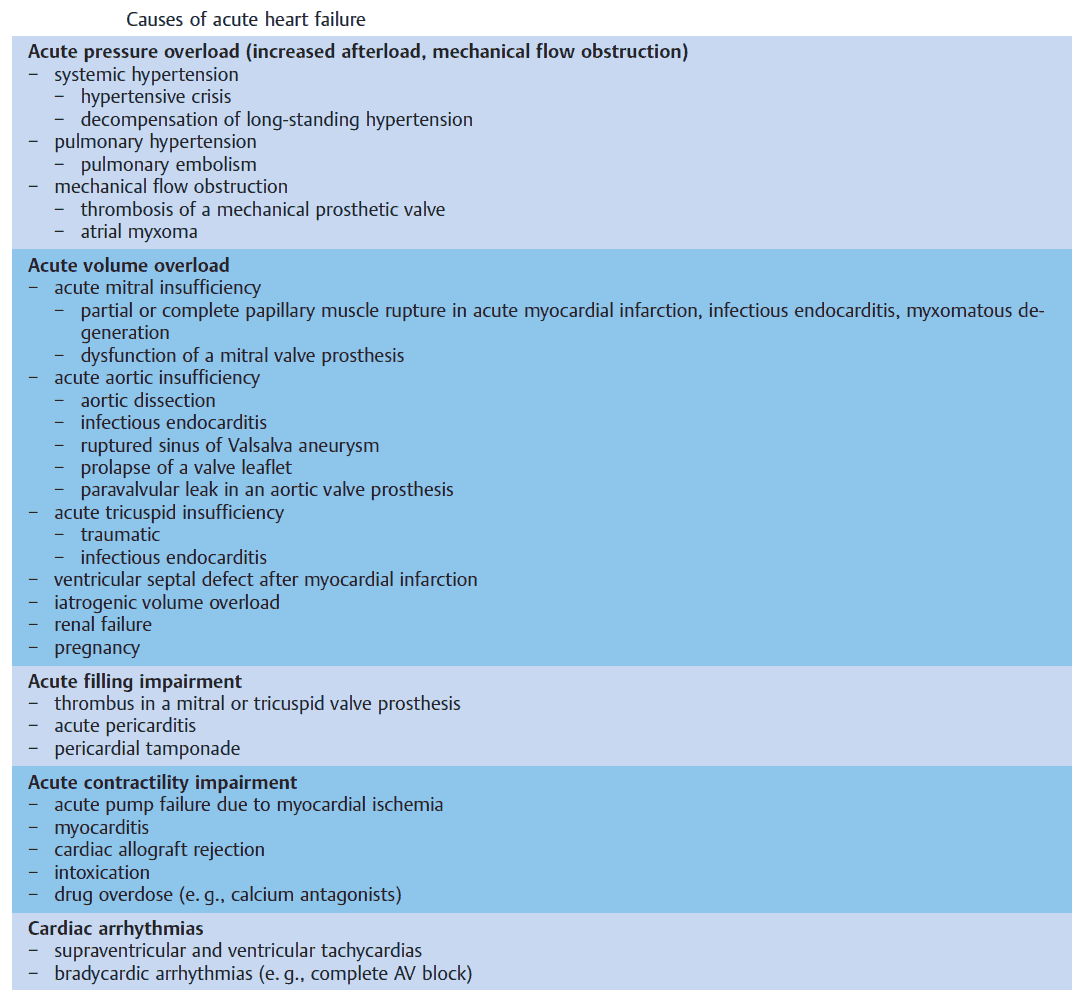

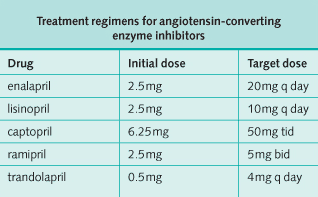

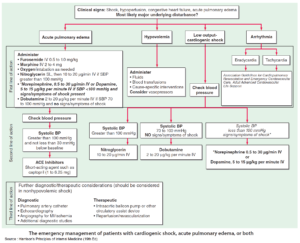

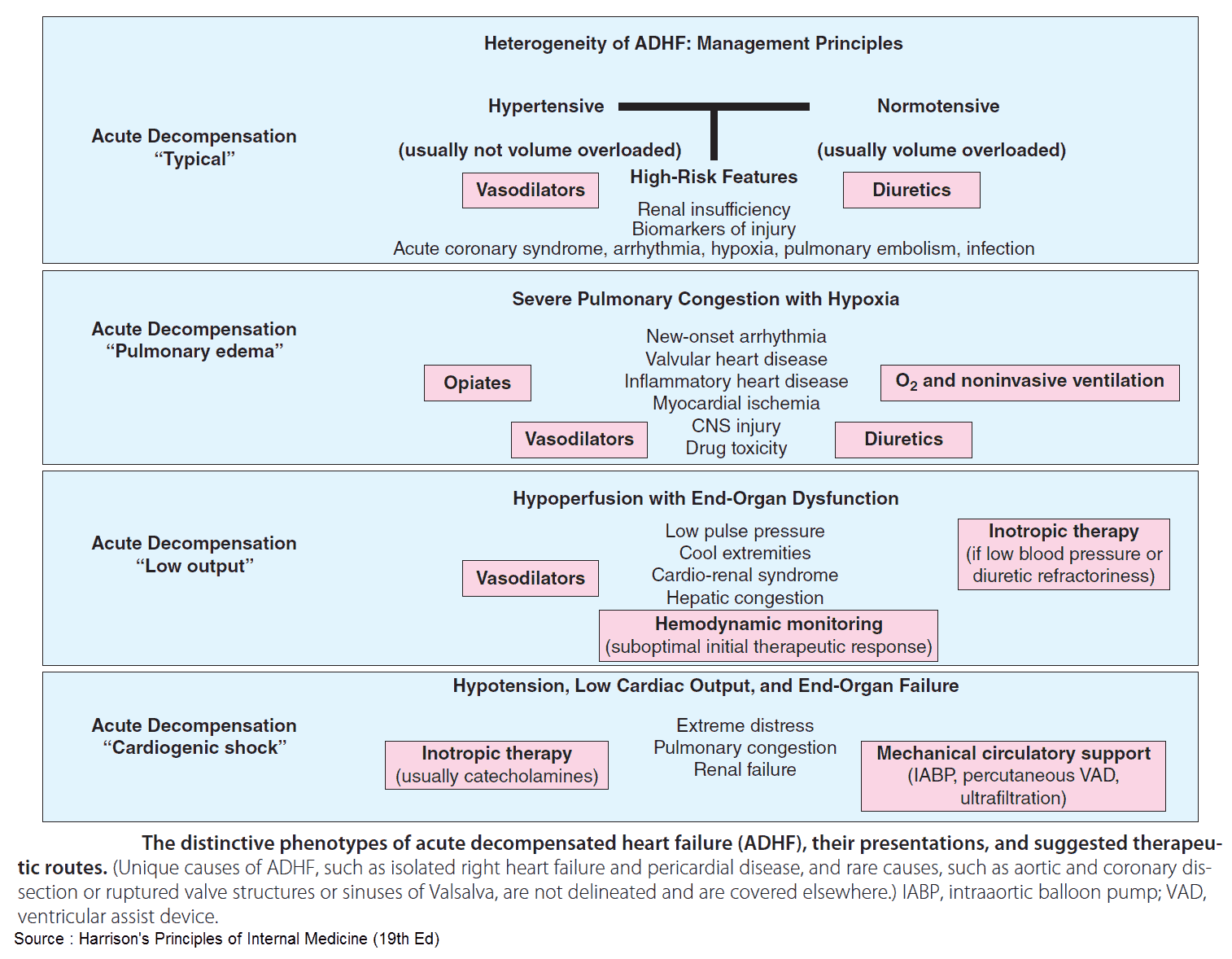

Acute heart failure

This is an emergency characterized by acute breathlessness, wheezing, anxiety, and sweating. There may be pink frothy sputum, as well as signs of pulmonary edema. If severe, the management (listed below) should begin before investigations are performed:

- Sit the patient upright.

- Give high-concentration oxygen unless there is coexisting chronic hypercapnia due to long-standing respiratory failure. It may even be necessary to ventilate the patient.

- Give intravenous furosemide or bumetanide. These cause an immediate vasodilatation, as well as their more delayed diuresis.

- Give 5 mg intravenous morphine slowly unless there is liver failure of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This causes sedation, relieves dyspnea, and causes vasodilatation. It should be given with an antiemetic.

- Give intravenous venodilators (e.g., nitrates, nitroglycerine) if systolic blood pressure is greater than 100 mmHg. This will reduce preload.

- Load the patient with digoxin, orally or intravenously, to slow the heart rate if the patient is in fast atrial fibrillation. Other arrhythmias should be treated appropriately. This can be done with an esmolol or diltiazem IV drip.

- Consider giving intravenous aminophylline 5 mg/kg intravenously over 10 minutes. This is positively inotropic and causes vasodilatation and bronchodilation. It is usually reserved only for those patients with bronchospasm.

- Intravenous inotropic agents may be of value if there is hypotension. If signs of renal hypoperfusion are present, dopamine is recommended intravenously at 2.5-5μg/kg/min. If pulmonary congestion is dominant, dobutamine is preferred at 2.5μg/kg/min, increasing gradually to 10μg/kg/min if needed.