Syncope is defined as a loss of consciousness that results from insufficient blood flow to the brain. Syncope accounts for more than 700,000 emergency department (ED) visits and 6% of hospital admissions each year in the United States. Though most etiologies are benign, a small portion of patients have a life-threatening cause of their syncope.

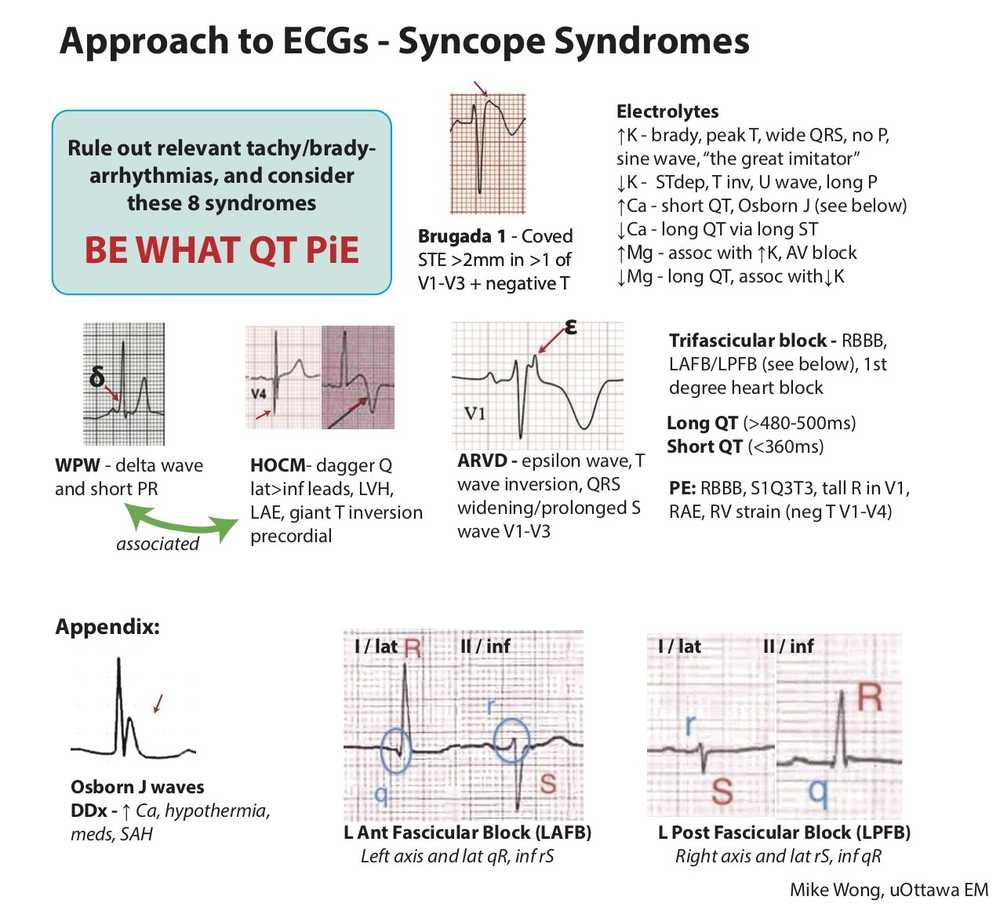

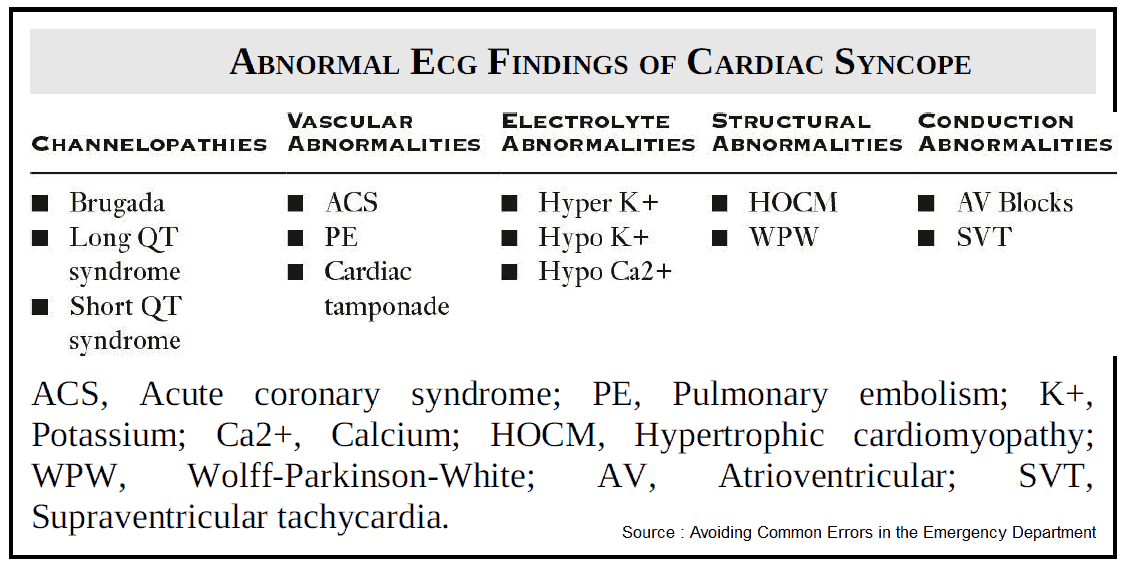

The history of present illness, physical examination, and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) are fundamental to the ED evaluation of a patient with syncope. In fact, it is often the ECG that provides critical clues to the etiology of potentially life-threatening causes of syncope.

In the ED patient with syncope, the ECG should be scrutinized for signs of ischemia, bradydysrhythmias, tachydysrhythmias, and conduction delays.

Additional critical diagnoses to consider that can be detected with the ECG include:

- Ventricular preexcitation syndromes

- Brugada syndrome

- Long or short QT syndromes

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia

- Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

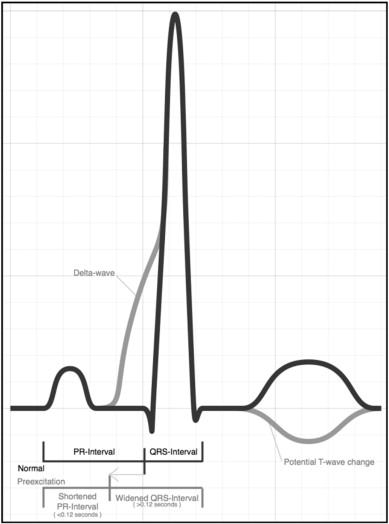

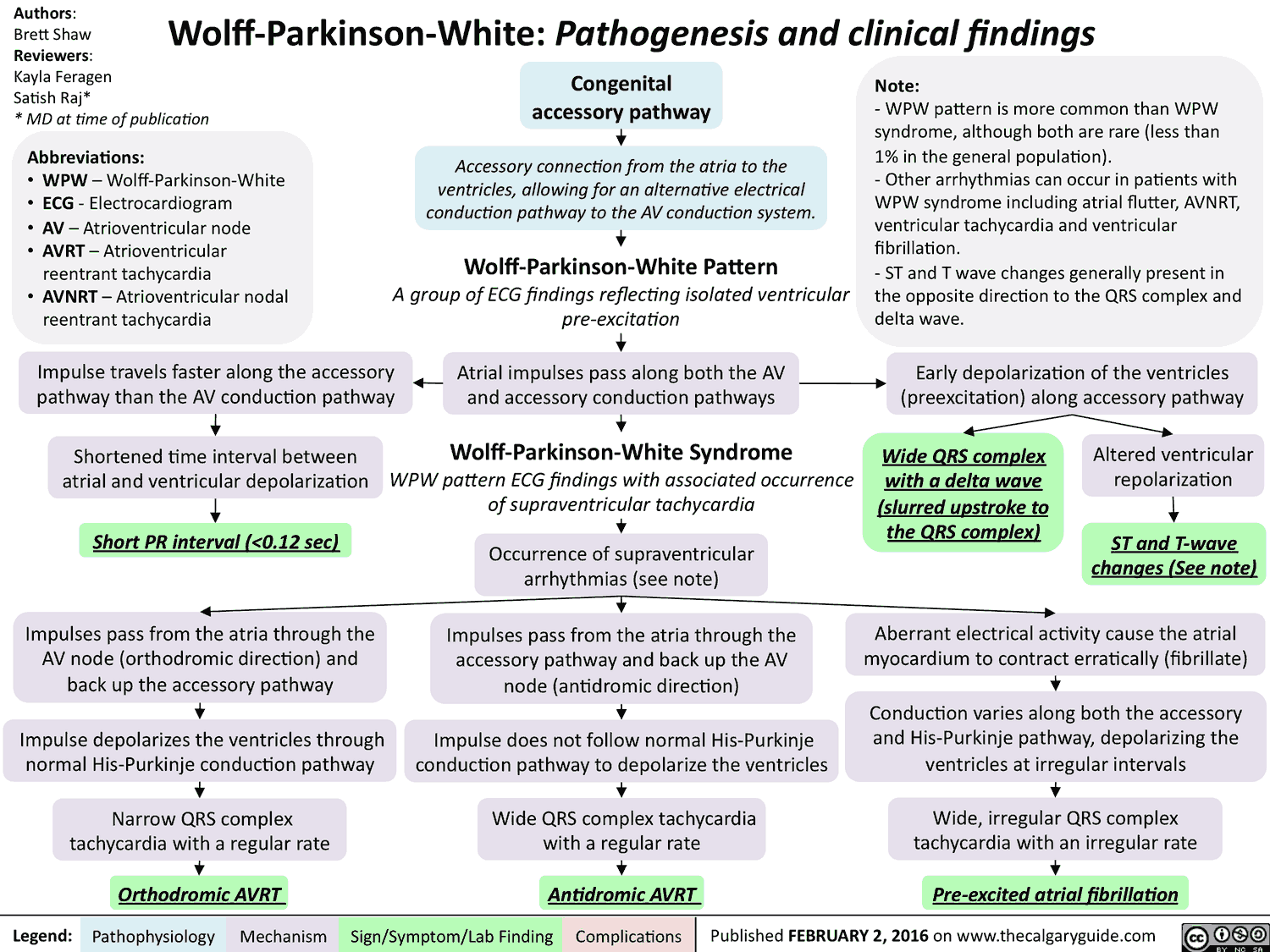

Ventricular Preexcitation (Wolff Parkinson White (WPW) Syndrome)

- PR segment < 120 ms

- QRS complex > 110 ms

- Slurred upstroke of the initial part of the R wave (delta wave)

- Type A: left-sided accessory pathway—delta wave in all precordial leads, R > S in lead V1

- Type B: right-sided accessory pathway—negative delta waves in leads V1 and V2

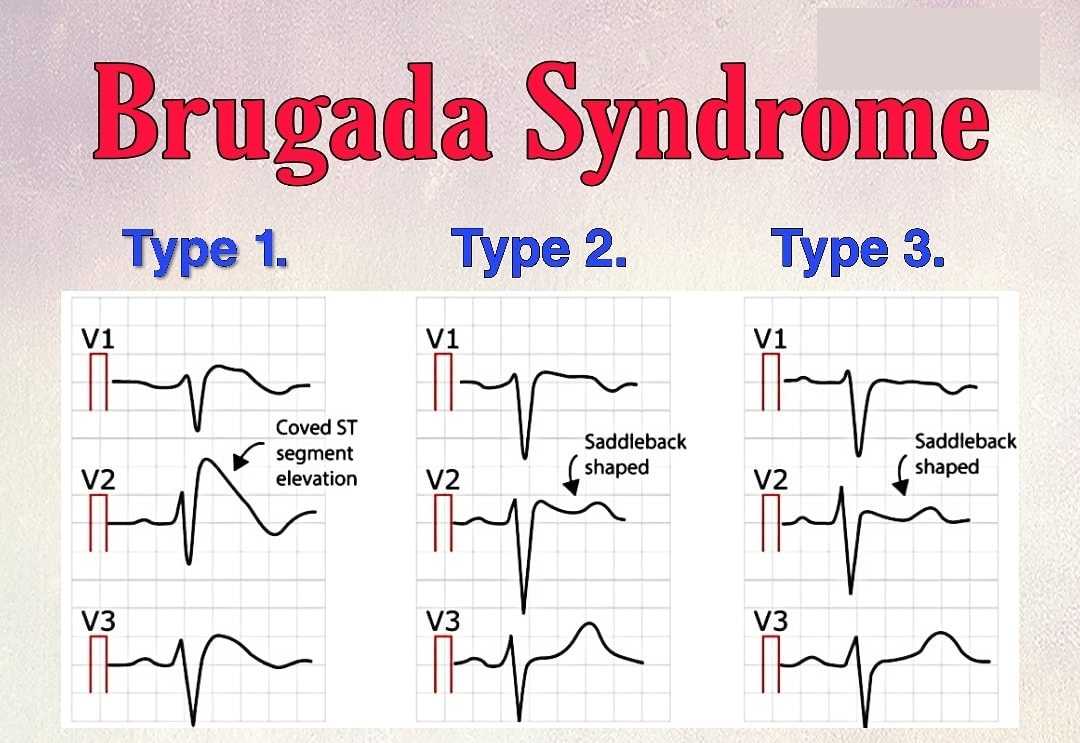

Brugada Syndrome

- Type 1

- Coved ST-segment elevation

- >2 mm of ST-segment elevation in 2 or more precordial leads (V1 to V3) followed by negative T wave

- Type 2

- Saddle back ST-segment elevation

- >2 mm of ST-segment elevation in 2 or more precordial leads (V1 to V3)

- Type 3

- Either type 1 or 2 with <2 mm ST-segment elevation

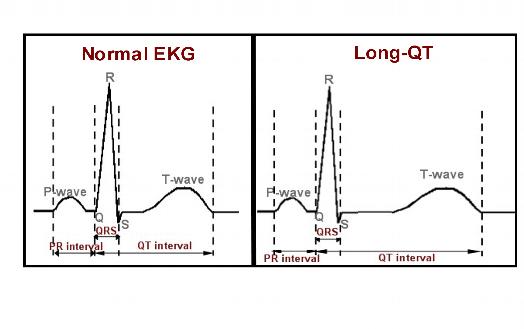

Long QT Syndrome

- QTc = QT/√R-R interval

- Prolonged if QTc > 440 ms in men or >460 ms in females

- Increased risk of dysrhythmias when the QTc > 500 ms

- Potential for a “R on T” phenomenon, where a premature ventricular contraction at the end of T wave can induce polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or torsades de Pointes.

- Etiologies to consider include electrolyte deficiencies (potassium, magnesium, calcium), hypothermia, cardiac ischemia, increased intracranial pressure, and toxins.

Short QT Syndrome

- Shortened if QTc < 330 ms in males or <340 ms in females

- Short, or absent, ST-segment with peaked appearance of the T wave

- Etiologies to consider include congenital shortening, digoxin toxicity, and hypercalcemia.

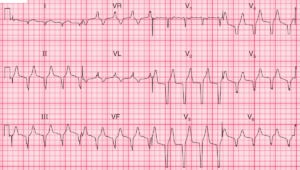

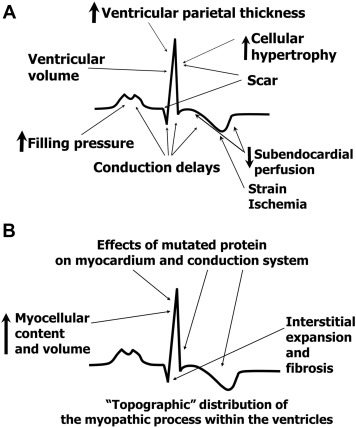

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

- Deep Q waves in the lateral (I, aVL, V5-V6) and inferior (II, III, aVF) leads

- Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)

- Left atrial enlargement

- Apical HCOM variant

- Localized hypertrophy of the LV apex

- LVH

- Giant T-wave inversions in the precordial leads

- Possibly inverted T waves in the inferior and lateral leads

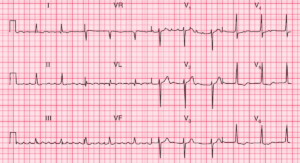

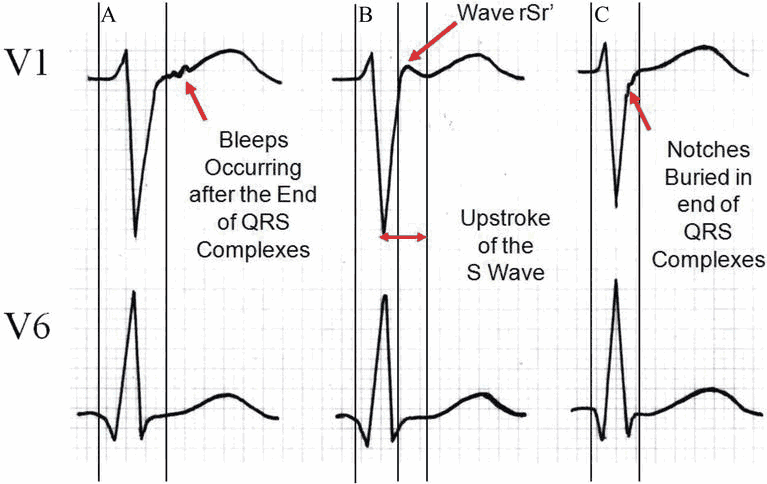

Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia (ARVD)

- Epsilon wave (small positive deflection at end of QRS complex) is the most specific finding and found in ~30% of patients.

- T-wave inversions in leads V1 to V3

- Prolonged QRS in leads V1 to V3 (100 to 120 ms)

- Slurred S-wave upstroke in leads V1 to V3 (50 to 55 ms)

- Consider ARVD in patients with paroxysmal episodes of ventricular tachycardia.

Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia

- ECG is typically normal at rest.

- Exercise classically induces ventricular tachycardia from adrenergic activation.

- Bidirectional tachycardia (alternating 180 degrees QRS axis beat to beat variation)

- Ventricular ectopy is often noted when the heart rate increases above 100 beats per minute.

Key Points

- An ECG should be performed on all ED patients with syncope.

- Scrutinize the ECG for signs of ischemia, conduction delay, tachydysrhythmias, and bradydysrhythmias.

- Be sure to look for signs of ventricular pre-excitation syndromes, Brugada syndrome, prolonged or short QT syndrome, ARVD, HOCM, and CPVT.

- Consider electrolyte abnormalities in the patient with QT interval abnormalities.

- The epsilon wave is the most specific finding for ARVD.

Suggested Readings

- Dovgalyuk J, Holstege C, Mattu A, et al. The electrocardiogram in the patient with syncope. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(6):688–701.

- Johnsrude CL. Current approach to pediatric syncope. Pediatr Cardiol. 2000;21(6): 522–531.

- Quinn J. Syncope and presyncope: Same mechanism, causes, and concern. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(3):277–278.

- Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Stiell IG, Wells GA, et al. Outcomes in presyncope patients: A prospective cohort study. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(3):268–276.e6.