Table of Contents

Introduction

Current diagnosis and treatment for abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) is driven by expert panel consensus guidelines. The most widely recognized source is the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (WSACS), which released its updated guideline in 2013.

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome occurs when elevated intra-abdominal pressure (IAP), or, intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH), leads to new organ dysfunction. The incidence of abdominal compartment syndrome in the ED has not been reported, but in studies of trauma patients, the incidence is between 1% and 14%.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Clinical signs of ACS can be broken down by organ system.

- In the brain, IAH impairs venous return, which increases intracerebral pressure and decreases cerebral perfusion pressure.

- In the heart, IAH increases intrathoracic pressure, which decreases venous return and cardiac output.

- In the lungs, IAH pushes up on the diaphragm, which decreases vital capacity and lung compliance leading to hypoxemia and hypercarbia.

- In the Gastrointestinal tract, IAH decreases abdominal perfusion pressure (APP), which is the mean arterial pressure minus IAP. Lower APP leads to mesentery hypoperfusion and poor lactate clearance.

- In the kidneys, IAH decreases renal blood flow, which manifests as acute kidney injury and oliguria.

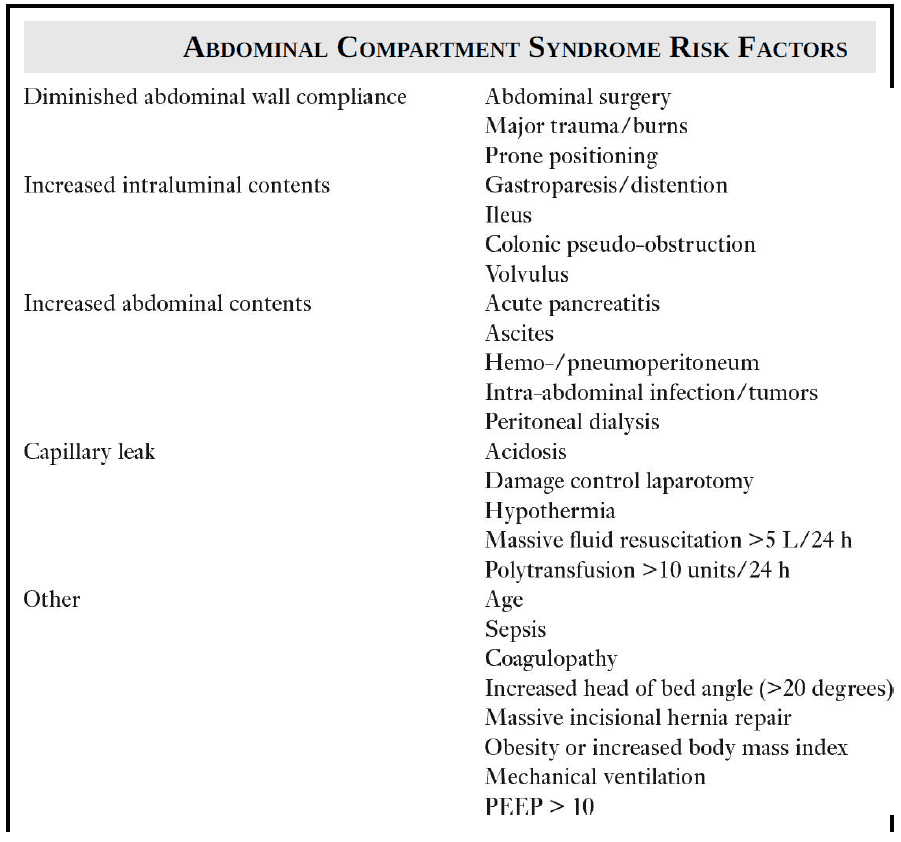

Causes and Risk Factors for Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Risk factors for Abdominal Compartment Syndrome can be grouped by mechanism.

Etiology of Abdominal Compartment Syndrome is divided into primary and secondary causes.

Primary causes include:

- bowel obstruction

- ascites

- pancreatitis

- trauma

- recent major abdominal surgery

- ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm.

These conditions often require early surgical or interventional radiology therapies.

Secondary causes of ACS are from nonabdomen/pelvis pathology and include:

Diagnosis of Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Physical exam, clinical signs, and imaging are not reliable in identifying Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Upon evaluation in an emergency setting, if a patient’s history contains any of the risk factors in Image, it is reasonable to consider ACS in the differential diagnosis.

Key exam and lab findings may include:

- abdominal distention

- progressive oliguria

- hypercarbia

- refractory hypoxemia

- lactic acidosis

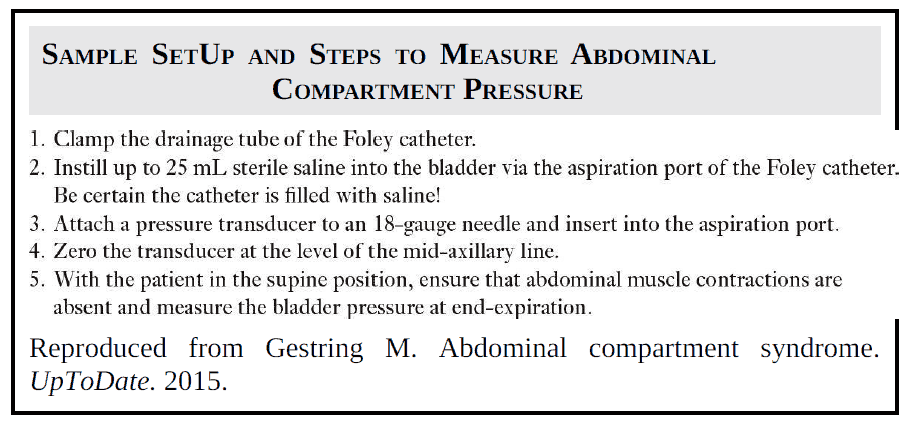

Ultimately, to objectively evaluate for IAH/ACS, it is necessary to measure IAP (intra-abdominal pressure) using transduced intravesicular pressures.

Peritoneal adhesions, pelvic hematomas/fractures, abdominal packing, or a neurogenic bladder may affect the accuracy of IAP measurement.

Patients with morbid obesity, pregnancy, or long-standing ascites could have chronically elevated IAP. Per WSACS definitions, IAP is the steady-state pressure within the abdominal cavity expressed in mm Hg and measured at end-expiration in the supine position.

Elevated IAP is considered to be IAH when it is ≥12 mm Hg. Normal IAP for healthy adults is 0 to 5 mm Hg. Normal IAP for critically ill adults is 5 to 7 mm Hg. For adults, ACS occurs when IAP is maintained above 20 mm Hg (for pediatrics, the threshold is 10 mm Hg) with new organ dysfunction. The diagnosis of ACS is not dependent upon APP values.

Treatment of Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Early recognition of ACS is crucial given the reported association with ~40% to 100% mortality. Several temporizing medical therapies can be implemented based on the suspected underlying mechanism for ACS.

- For abdominal wall compliance, appropriate pain and sedation meds should be used; trials of neuromuscular blockade to reduce muscle tone can be attempted and, if the patient’s cardiovascular and respiratory status allow for it, supine positioning.

- For increased intraluminal contents, nasogastric and rectal decompression may help lower IAP.

- For increased intra-abdominal contents such as ascites, hematoma, or abscess, ultrasound-guided paracentesis in the ED or percutaneous drainage by interventional radiology should be considered, respectively.

- At this time, WSACS has no recommendations regarding diuretics or albumin usage.

In an emergency setting, if there is concern for ACS, first obtain an IAP. If it is above 12, begin appropriate medical therapies to lower IAP, obtain an early surgical consult, and measure IAP every 4 hours.

If the IAP does not drop or organ dysfunction progresses, medical management is considered unsuccessful and surgical intervention is recommended.

Decompression laparotomy is considered the definitive treatment for Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. The threshold for decompression is not well established. Some surgeons use an IAP of 25 mm Hg, others use between 15 and 25 mm Hg, and still others use an APP under 50 mm Hg. After decompression, the abdomen is left open with temporary abdominal wall closure via dressings that bridge the fascia. The disposition for ACS patients is to a surgical ICU.

Key Points

- Common ED cases to suspect ACS: bowel obstruction, ascites, pancreatitis, trauma, recent major abdominal surgery, massive resuscitation / transfusion, shock, and severe burns.

- Key findings that may indicate ACS: abdominal distention, progressive oliguria, hypercarbia, refractory hypoxemia, and lactic acidosis.

- Use transduced bladder pressures to measure IAP: ≥12 mm Hg is IAH; >20 mm Hg with new organ dysfunction is ACS.

- In the ED, utilize temporizing medical therapies as indicated.

- Obtain early surgical consultation for possible decompression laparotomy.