Table of Contents

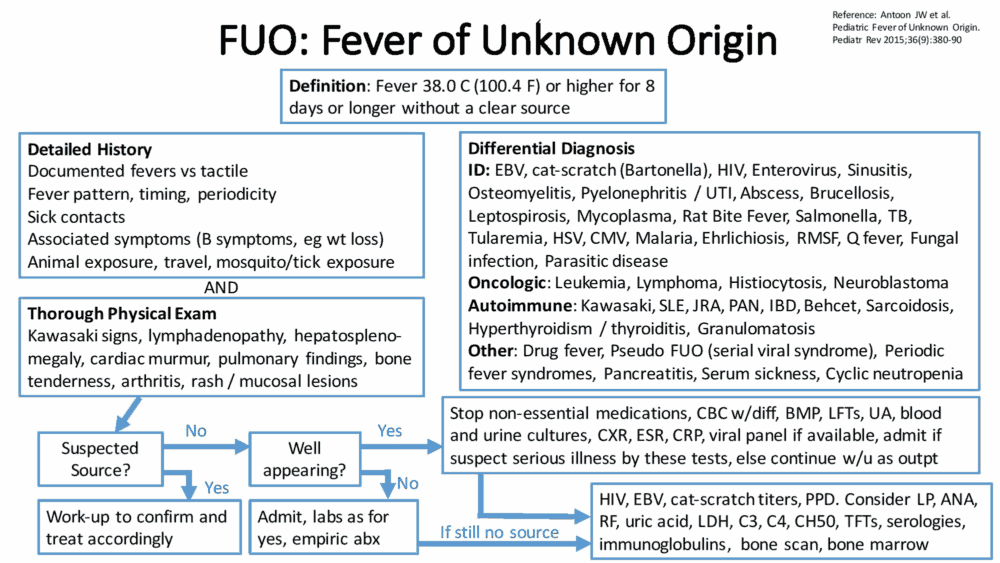

Definition of Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO)

Most fevers are due to viral illnesses and are self-limiting. Fever of unknown origin (FUO) is a persistent and unexplained fever that lasts more than 3 weeks.

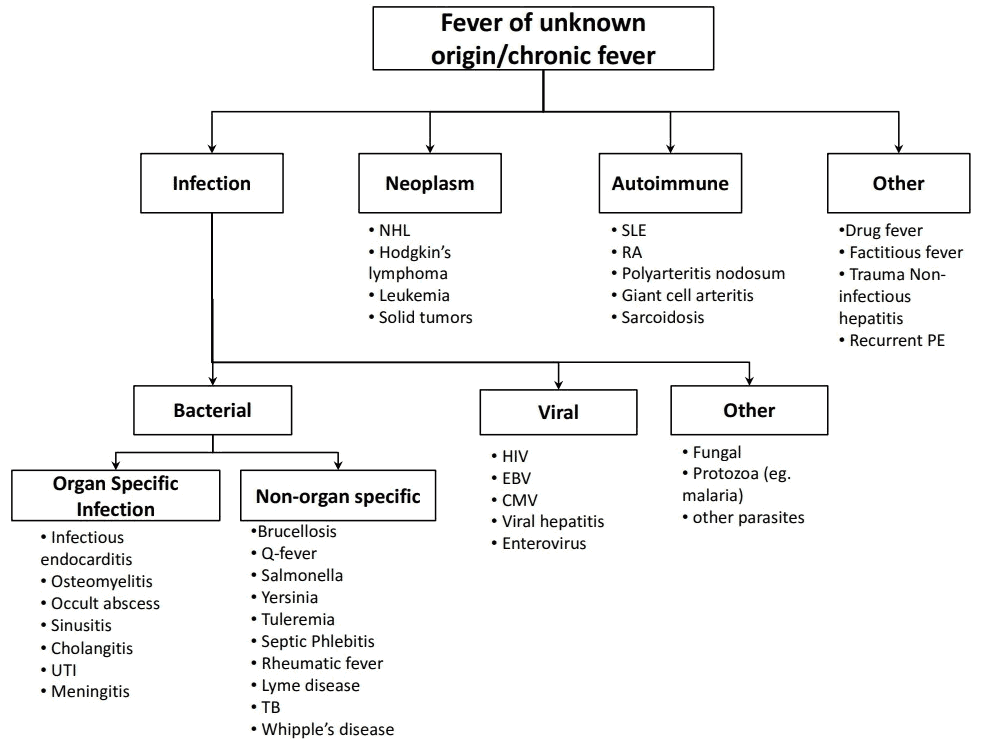

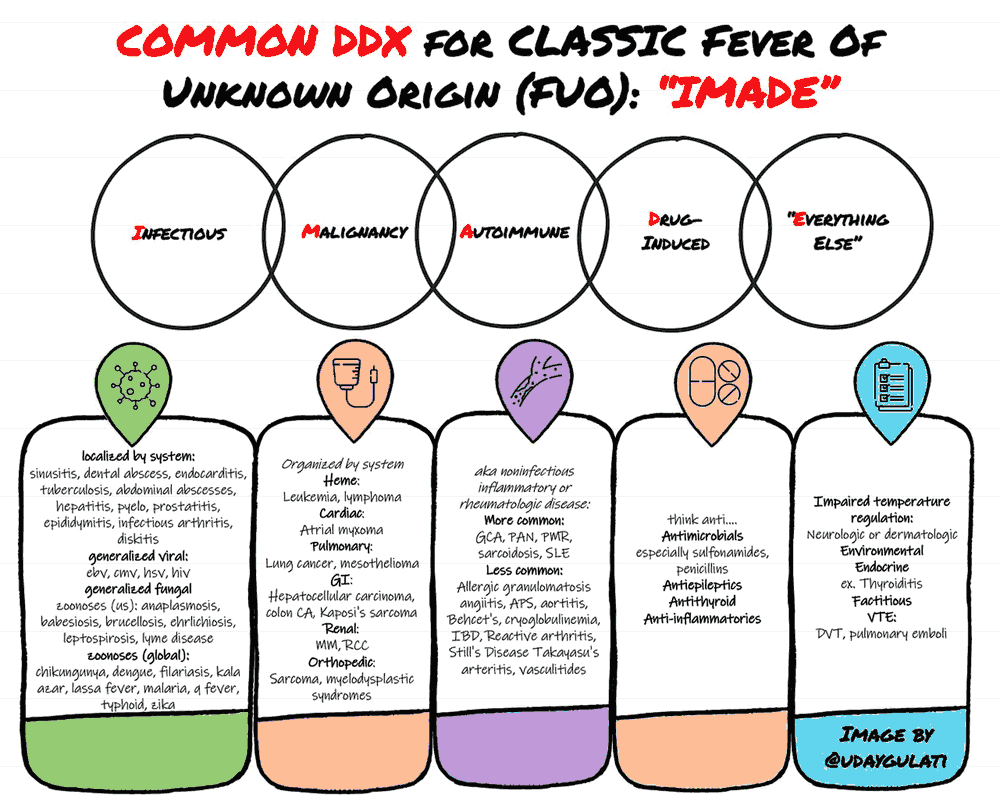

Causes (Etiology) of Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO)

The causes of Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO) depend largely on the patient population and previous medical history. For instance, an HIV-positive patient has a much larger differential diagnosis that starts with infections and lymphomas as a possible cause for fever.

In general, Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO) may be caused by the following:

- Infections: 20-40%.

- Connective tissue disorders: 20%.

- Malignancy: 10-20%.

- Undiagnosed: 20%. Drugs (e.g., phenytoin): rare.

History in the Patient with Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO)

This should be thorough. Note especially:

- Foreign travel: the incubation period of many tropical diseases may mean that the fever starts some time after arrival back home.

- Contact with animals (zoonoses), such as leptospirosis, Q fever, salmonellosis, cat-scratch fever, psittacoses and ornathoses, toxoplasmosis, hydatid disease, toxocariasis, meningitis, anthrax.

- Contact with infected people (e.g., tuberculosis).

- Sexual history.

- Alcohol intake.

- Previous illnesses.

- Previous surgery or accidents.

- Recent hospitalization or recent dental, GI, GU, or respiratory work.

- Previous known valvular disease or prosthetic material

- Rashes.

- Diarrhea.

- Ask about illicit drug use, especially any IV use, because this greatly increases the risk for bacterial endocarditis.

- A full history of medication, including over-the-counter drugs.

- Immunization history.

- Symptoms such as sweats, weight loss, and itching (these suggest a hematologic malignancy).

- Immunosuppression (transplant patient, previous autoimmune disease, HIV).

- Lumps.

- Familial disorders (e.g., familial Mediterranean fever).

Every symptom should be explored in detail. The diagnosis should be made by going over the history repeatedly to look for additional or missed clues.

The temperature and pulse should be recorded at least 4-hourly when a patient is admitted with Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO).

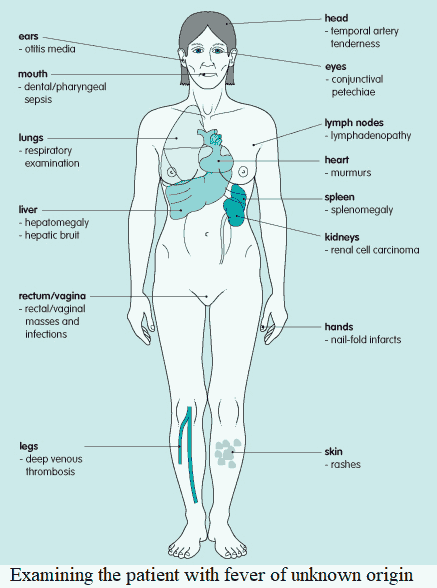

Examining the Patient with Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO)

The examination of a patient with Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO) should be especially thorough and may need to be repeated several times. Particular attention should be given to:

- Teeth and throat.

- Temporal artery tenderness (if this is suspected, ask about jaw claudication or any visual changes that the patient has experienced).

- Eye signs (e.g., conjunctival petechiae).

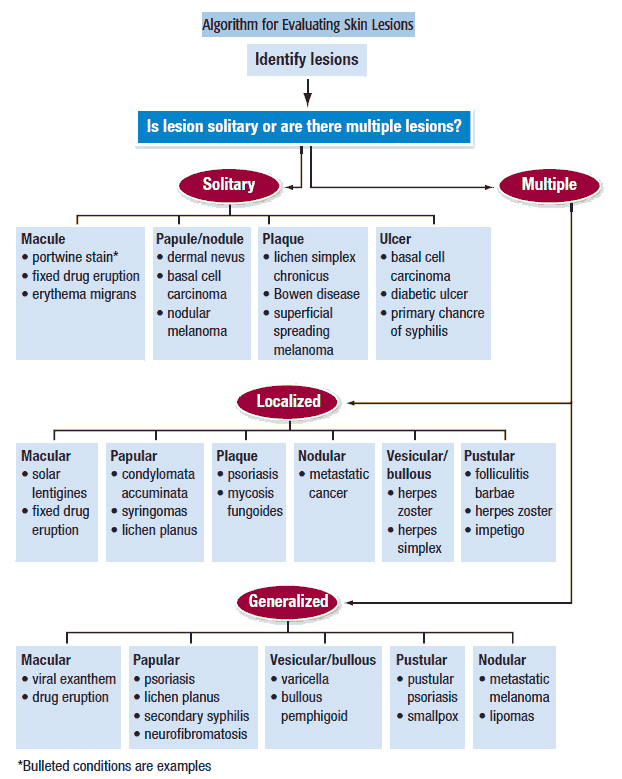

- Skin lesions (e.g., rashes, petechiae, and infarctions).

- Look for Janeway lesions and Osler’s nodes (which are painful).

- Lymphadenopathy and organomegaly.

- Cardiac murmurs.

- Rectal and vaginal examinations.

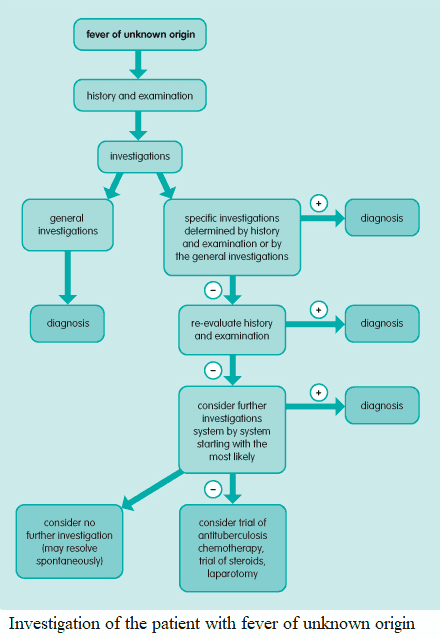

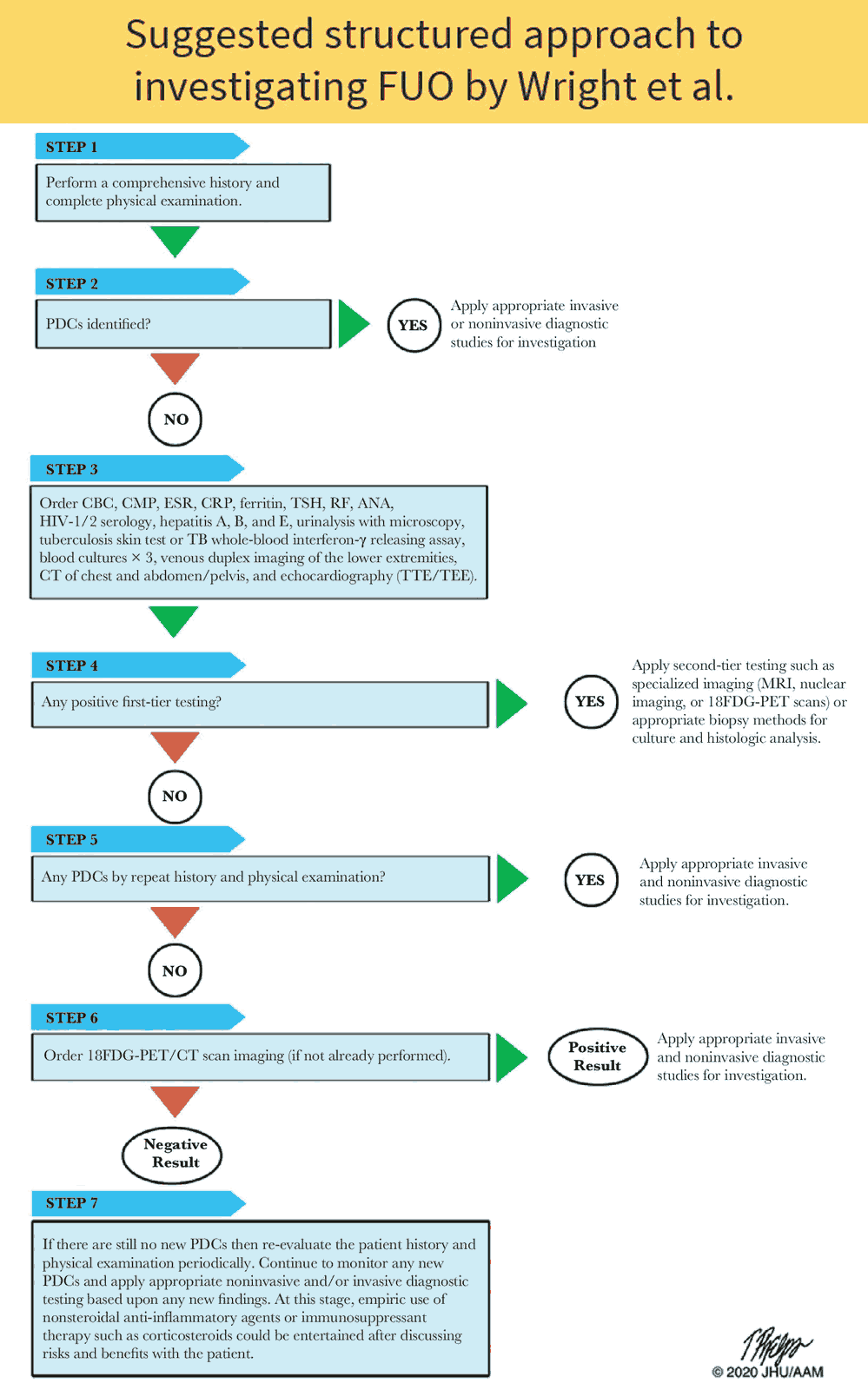

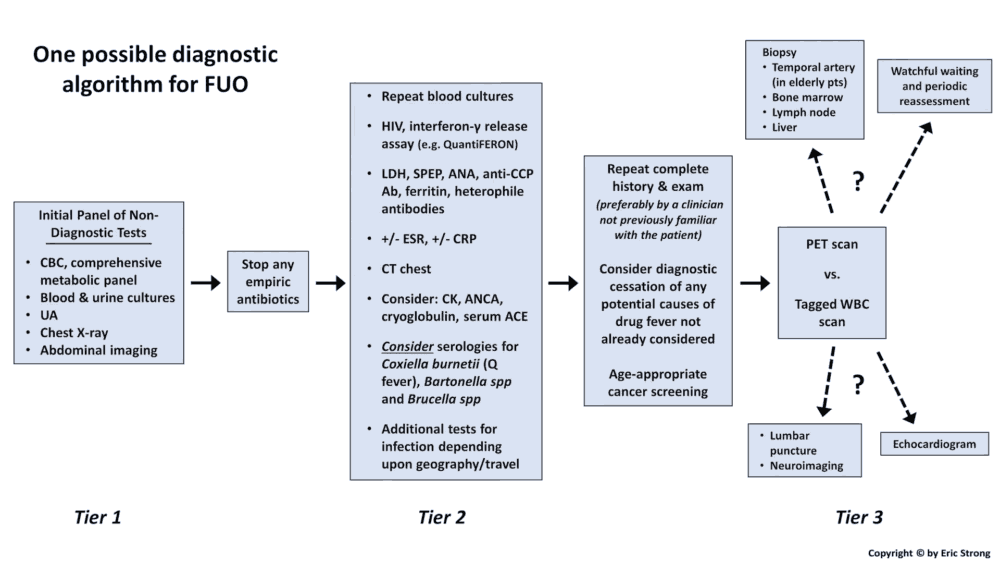

Investigating the Patient with Fever of Unknown Origin (FUO)

Investigations are best directed from the history and examination. For example, if the patient has just returned from a part of the world where malaria is endemic, thick and thin blood films should be requested.

Often there will be no clue, and the best way to proceed is to ask for general nonspecific screening tests, which may then suggest an area to focus on.

Complete blood count and differential white cell count

Complete blood count and differential white cell count may yield information on the following:

- Neutrophil leukocytosis: bacterial infections, myeloproliferative disease, malignancy (e.g., hepatic metastases), collagen vascular diseases.

- Leukopenia: viral infections, lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus, brucellosis, disseminated tuberculosis, drugs.

- Monocytosis: subacute bacterial endocarditis, inflammatory bowel disease, Hodgkin’s disease, brucellosis, tuberculosis.

- Abnormal mononuclear cells: glandular fever, cytomegalovirus infection, toxoplasmosis.

- Eosinophilia: parasitic infections such as trichiasis, hydatid disease (infection with the echinococcus tapeworm), malignancy (especially Hodgkin’s disease), pulmonary eosinophilia

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

A very high erythrocyte sedimentation rate suggests the following:

- Multiple myeloma.

- Rheumatic fever.

- Lymphoma.

- Subacute bacterial endocarditis.

- Autoimmune diseases, most of which have an elevated ESR (e.g., SLE, temporal arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (Still’s disease))

Basic metabolic panel

Assessment of urea and electrolytes may reveal renal impairment or hyponatremia due to pneumonia.

Liver function tests

Abnormal results may lead to more detailed investigations of the liver. Note, however, that alkaline phosphatase may also be raised in metabolic bone disease, Hodgkin’s disease, Still’s disease, and in patients with bony metastases.

Bacteriology and serology

Microscopy and culture from every site possible:

- Urine: bacteria (infections), hematuria (may suggest subacute bacterial endocarditis or hypernephroma).

- Blood cultures: several samples are needed from different veins at different times of the day.

- Feces microscopy for ova, cysts, and parasites.

- Vaginal and cervical swabs.

- Urethral swabs in men.

- Sputum microscopy and culture.

- Throat swab cultures.

- Amylase/lipase: will show pancreatitis.

- Liver function tests: will show hepatitis.

With regard to serology, many specific tests are available (e.g., glandular fever, psittacosis, brucellosis). A second sample must be taken 2-3 weeks later to show a rising antibody titer or IgM titers may signal acute infection.

Chest x-ray

Chest x-ray should be performed to show, for example, tuberculosis, subphrenic abscess, and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (sarcoidosis).

Further investigations

Further investigations should be directed by the results of previous investigations. For example, if a renal problem is suspected, further tests might include an intravenous pyelogram and renal ultrasound. If a pulmonary problem is suspected, a ventilation/perfusion scan or pulmonary angiography may be useful to exclude multiple pulmonary emboli as the cause of FUO.

If there are no clues from previous investigations, the following further investigations should be considered:

- Echocardiography: to rule out endocarditis (needs to be transesophageal echocardiography).

- Immunoglobulins: raised immunoglobulin (IgG) suggests SLE or chronic hepatitis; raised IgM suggests viral hepatitis; raised IgA suggests Crohn’s disease.

- Rheumatoid factor.

- Intradermal PPD test for tuberculosis.

- Bone marrow aspiration.

- Lumbar puncture.

All nonessential drugs should be stopped on admission. It may be necessary to withhold other drugs at this stage, one at a time for 48 hours each.

If there is still no clue as to the cause of the fever, the system most likely to be responsible should be investigated. Thus, to investigate the abdominal system, the following investigations should be considered:

- Abdominal ultrasound (e.g., subphrenic or pelvic abscess).

- Abdominal computed tomography scan (e.g., retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, lymphoma).

- Barium studies (e.g., malignancy or abscess).

- Liver biopsy (e.g., granulomatous diseases or brucellosis).

Very rare causes should be considered if not already investigated. These include hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma, and familial Mediterranean fever.

Factitious fever is caused by the deliberate manipulation of the thermometer. This is classically said to occur in young women. The diagnosis should be suspected if other causes have been excluded; if there is no evidence of a chronic illness and no increase in pulse rate during fever; or if the patient looks inappropriately well despite fever.

If all else fails, it may be necessary to carry out an exploratory laporotomy, although the postoperative complication rate is 15-20%. Consideration should also be given to treating tuberculosis with antituberculosis chemotherapy, endocarditis with antibiotics, and vasculitides with steroids.