Table of Contents

Introduction and Clinical Terms

“Too infrequent, too little, too hard” are words with which patients that seek medical attention for constipation describe their bowel habit. In everyday clinical practice constipation can be defined as less than two bowel actions per week, usually passing hard stool, and associated with straining. However, when applying this definition it must be kept in mind that two to three bowel actions per week and small stool volumes may be physiological, depending on the volume and type of food ingested.

Classification

In the clinic it is important to distinguish

- acute constipation

- chronic constipation (duration more than three months)

Every lasting change of bowel habit with sudden onset should be classified as acute constipation and requires urgent investigation. This includes “paradoxical” or “overflow” diarrhea that follows fecal impaction in the distal colon and anorectum with secondary dissolution and passage of liquid stool.

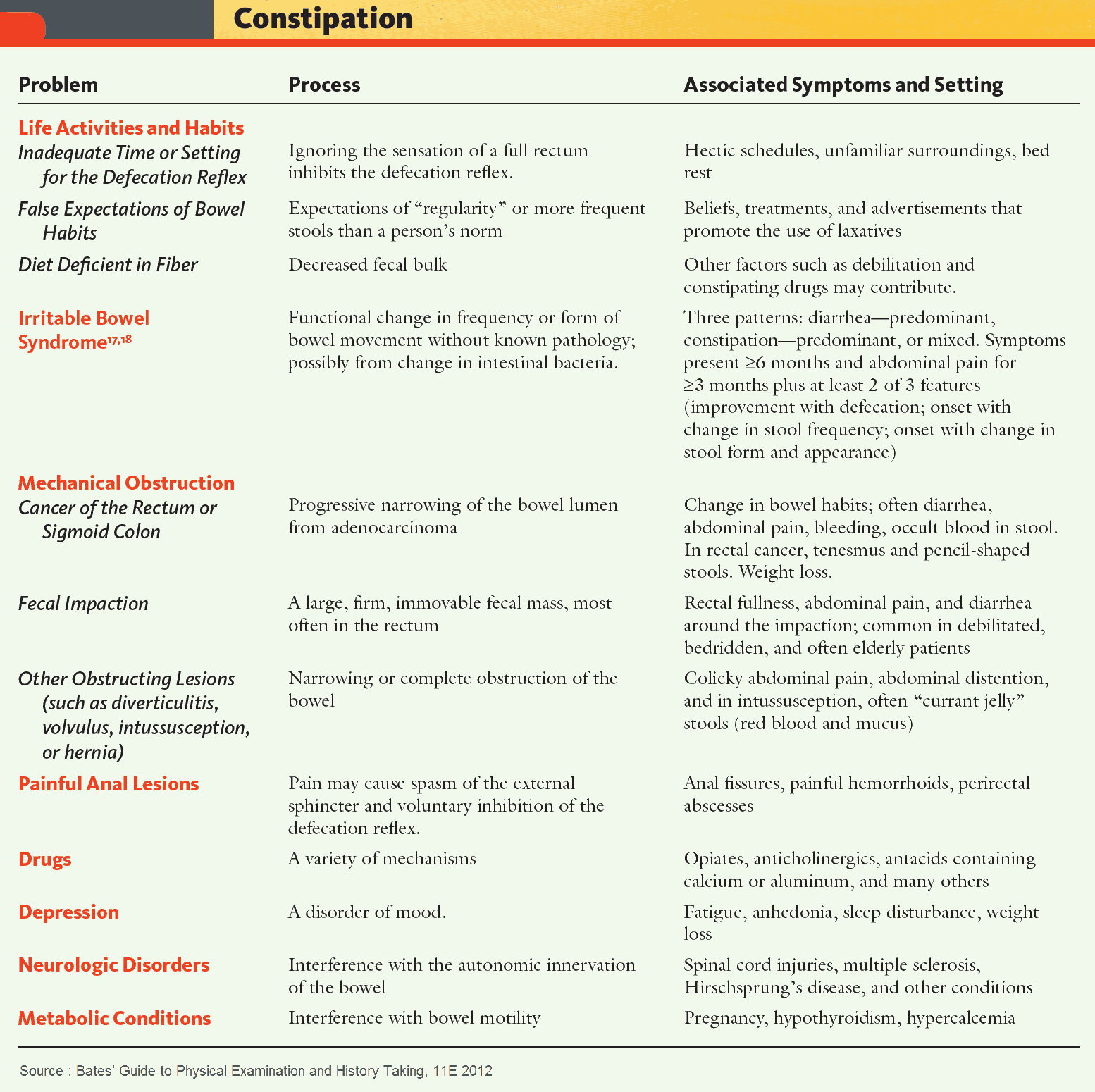

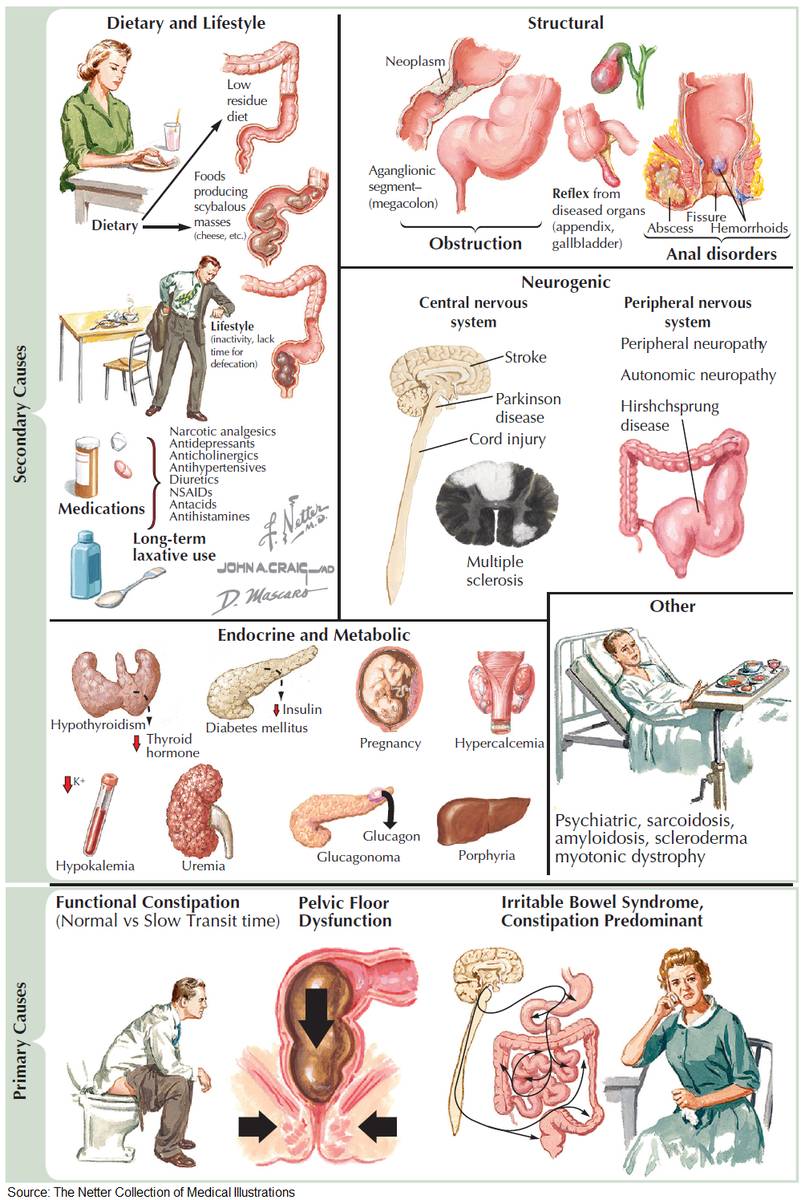

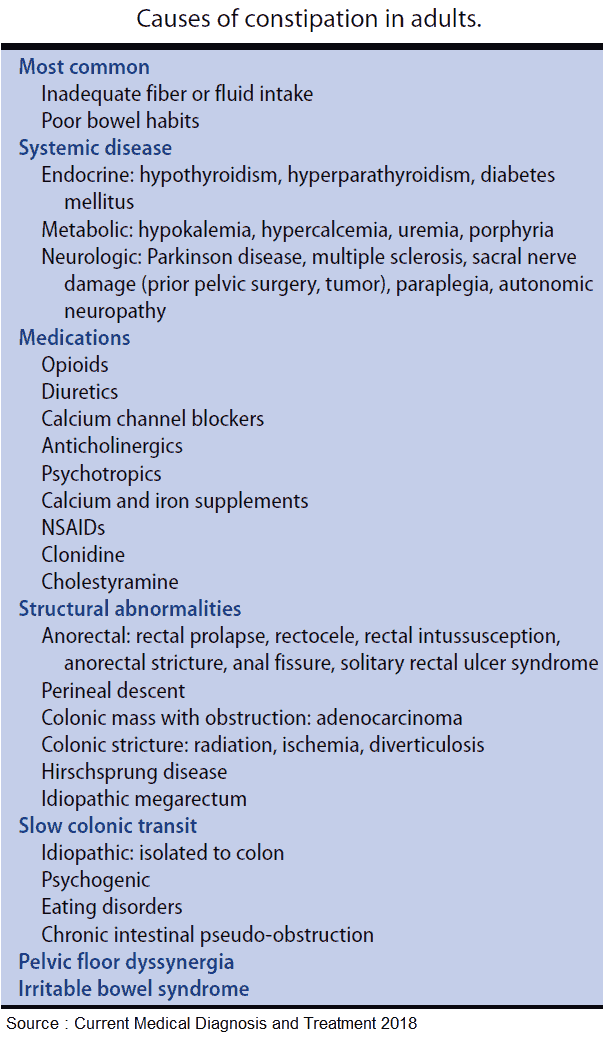

Pathophysiology of constipation:

- mechanical obstruction, e. g., colorectal carcinoma, anal carcinoma, diverticular disease

- disturbed colorectal motor function, e. g., slow transit, pregnancy, hypothyroidism, porphyria, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, medication (opiate, tricyclics), toxin (lead)

- disturbed neurological function (peripheral or central), e. g., Hirschsprung disease, major psychiatric disease (depression, psychosis), irritable bowel syndrome

- disturbed toileting behavior, e. g., anismus, painful defecation (anal fissure, thrombosed hemorrhoid), change of routine (work, travel), hospitalization

- miscellaneous, e. g., dietary factors (poor fluid intake, low-fiber), anorexia nervosa, underlying systemic disease.

Alarm symptoms must be sought in all patients presenting with constipation, especially those with a change in bowel habit over age 45, with rectal bleeding, weight loss, or a family history of bowel cancer. These features increase the risk that the patient has an underlying colorectal cancer or colitis.

Causes of Constipation

Acute Constipation

Patients presenting with constipation of sudden onset, especially in older age, must be investigated to exclude a colonic stenosis such as carcinoma or diverticular disease (muscle wall thickening and/or inflammation). Abdominal pain and increasing bloating are further indications of a mechanical bowel obstruction.

Polyps can cause similar symptoms, either due to obstruction or by acting as a focus for intussusception. Intraintestinal problems such as inflammatory strictures (e. g., Crohn disease) or ingested foreign bodies may cause acute constipation, as may extraintestinal disease (especially urogenital tumors).

Further causes of acute constipation can be identified by detailed questioning. These include anal disease (e. g., anal fissure), drugs (e. g., opiate, tricyclics, anticholinergics, calcium antacids), sudden changes in lifestyle (e. g., travel), diet (e. g., low fiber) or activity (e. g., hospitalization).

Chronic Constipation

Chronic constipation is very common and may be the result of a number of pathophysiological mechanisms, including colonic motor and neurological dysfunction, abnormal toileting behavior and dietary problems; several of which may be present in any one patient.

Constipation is often associated with “slow transit” of the stool through the colon. Colonic transit time can be assessed, and the severity of any disturbance quantified by the passage of radio-opaque markers through the gastrointestinal tract. Chronic constipation may also be caused by disorders of anorectal function (e. g., functional outlet obstruction).

Pathogenesis

The passage of stool through the bowel proceeds in a stepwise fashion by phasic contraction of the colonic musculature and mass movement of luminal contents, which occur at discrete intervals during the day. The transit time from cecum to anus is normally 12−24 hours.

Mass movements are often initiated by visceral events, such as the gastrocolic reflex after eating. Contraction of the distal colon and the passage of stool into the rectum trigger the urge to defecate. Should this important signal be suppressed on a regular basis, the sensation of urgency can be lost and this may lead to fecal loading and slow colonic transit.

Other factors that lead to chronic constipation by reducing fecal volume or inhibiting normal colonic function include reduced fluid intake, low-fiber diet, reduced physical activity, and the effects of a stressful (but sedentary), modern lifestyle. It is often difficult to identify a single cause of chronic, functional constipation in an individual.

Constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome is distinguished from functional constipation by the presence of abdominal pain relieved by defecation. Abdominal wind and bloating, as well as occasional episodes of loose stool and diarrhea (irritable bowel syndrome with alternating constipation/diarrhea), may also be prominent in this condition.

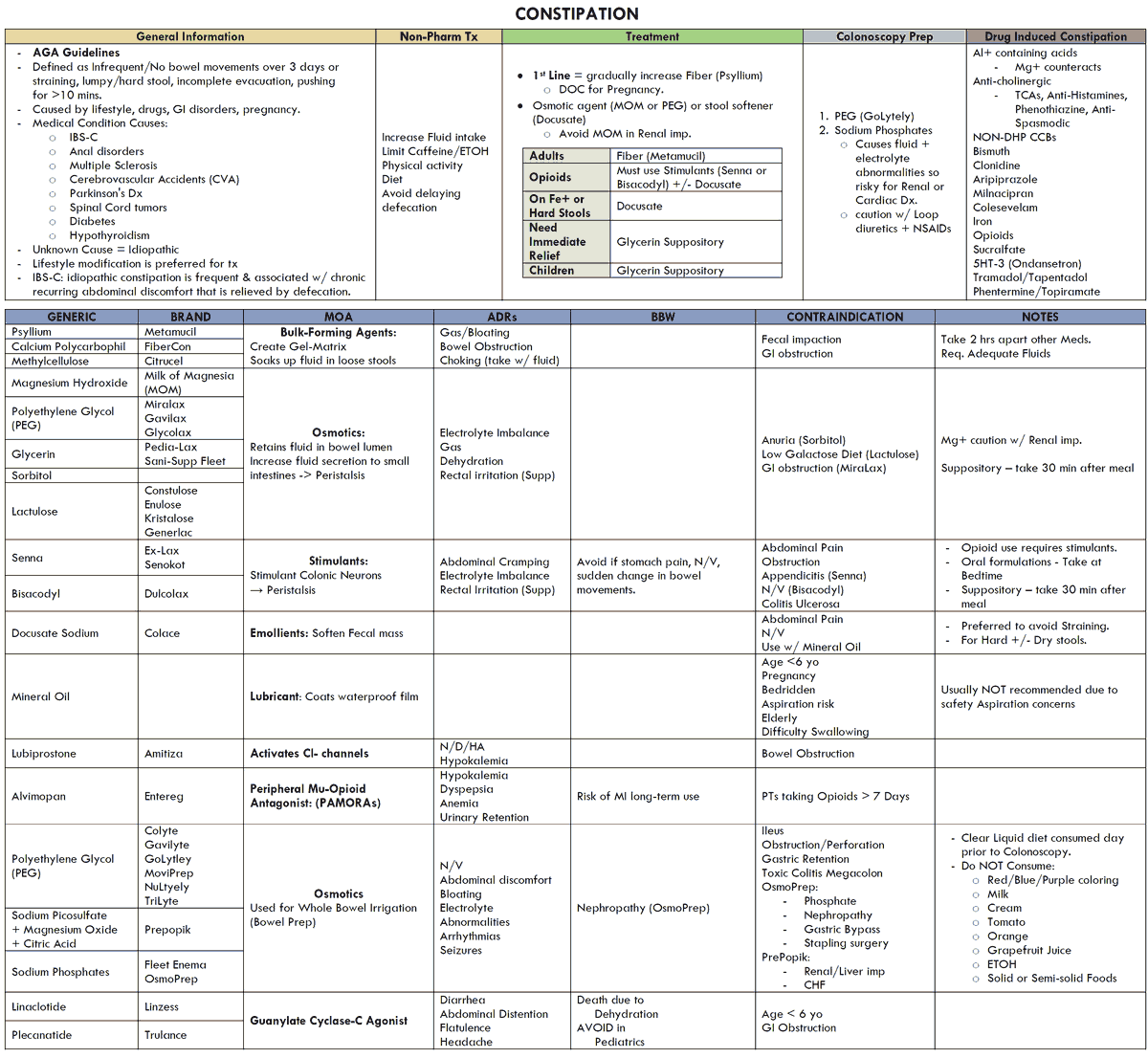

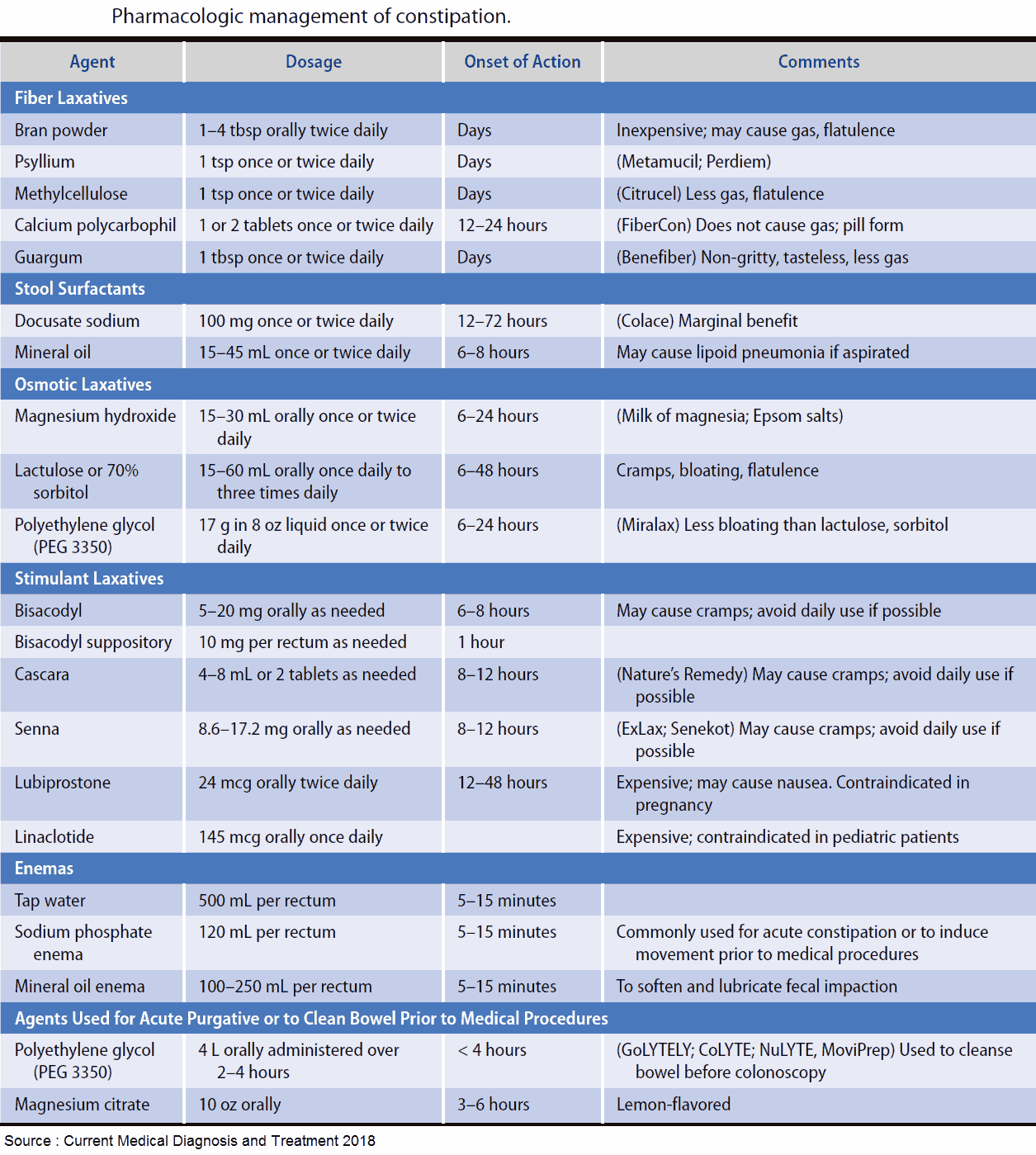

Therapy

For best effect, the treatment of constipation often needs to address several factors simultaneously: management of abnormal toileting behavior, improvement of stool volume and consistency by increasing fluid and fiber (also bulking agents and laxatives), and encouragement of physical activity.

Temporary Constipation

Chronic functional constipation can last for years. However, temporary problems with constipation can develop as a direct or indirect effect of underlying medical conditions:

- Hormonal factors are responsible for constipation associated with pregnancy and hypothyroidism and hyperparathyroidism.

- Visceral pain and inflammation associated with gallstones, renal colic, peptic ulceration, pancreatitis, and intra-abdominal infection may cause severe, resistant constipation.

- Major psychiatric conditions (especially depression), Parkinson disease, cerebrovascular disease, brain and spinal lesions are often associated with constipation.

- Constipation is prominent in patients affected by administration of exogenous (e. g., opiate abuse, lead poisoning) or the accumulation of endogenous (e. g., porphyria) toxins.

- Various drugs cause constipation (e. g., opiate analgesia, sedatives, anticholinergics, calcium-containing antacids, iron preparations, or ganglion blockers).

Intestinal Pseudo-Obstuction Syndrome

Pseudoobstruction is a syndrome that presents with symptoms and signs of colonic obstruction in the absence of an objective, mechanical lesion. It presents either acutely or as a chronic relapsing condition. The etiology may be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to a number of underlying diseases (neuromuscular disorders, scleroderma, endocrine conditions [e. g., hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism], retroperitoneal malignancy, severe psychiatric conditions, or drugs).

Anorectal Dysfunction

Functional obstruction of defecation can be the result of anismus or pelvic floor dysfunction. These problems can be identified only by investigation of anorectal function (proctoscopy at rest and on straining, anal manometry, defecography).

In patients with anismus, the muscle of the anal sphincter contracts rather than relaxes during attempted defecation. In patients with weak pelvic musculature (most common in women with multiple vaginal deliveries), the normal descent of the pelvic floor on straining is exaggerated. The lack of effective support results in inefficient expulsion of stool on attempted defecation. Moreover, the normal anatomic relationship between rectum and anal canal is altered, such that the direction of forces on straining are no longer directed through the anal canal, resulting in a functional outlet obstruction.

Megacolon and Megarectum

Constipation is the most important symptom in megarectum. Congenital aganglionosis of the myenteric plexus (Hirschsprung disease) is to be differentiated from acquired megarectum in which the myenteric plexus is preserved. However, in both forms a massively dilated colon is seen on radiography.

Congenital Megacolon

Hirschsprung disease usually presents shortly after birth or in early childhood with abdominal distension, severe constipation, and signs of partial intestinal obstruction.

The cause of this functional obstruction is the absence of ganglion cells in themyenteric plexus in the rectum and a variable length of distal colon. This pathology results in tonic contraction (spasticity) of the muscle wall and failure of the affected segment to accommodate and transmit stool. “Short-segment” Hirschsprung disease, affecting only the distal rectum, occasionally presents in adulthood.

The diagnosis is established by the absence of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex on manometry and full thickness biopsy of the affected bowel.

Acquired Megacolon

Acquired megacolon or megarectum is characterized by gross chronic dilation of the rectum and colon without severe inflammation (toxic megacolon), and without a spastic, aganglionic segment of distal colon or rectum. In adults, megarectum and megacolon can be observed in association with various underlying diseases including degenerative neuromuscular conditions, scleroderma, Parkinson disease, amyloidosis, hypothyroidism, porphyria, and Chagas disease. However, the etiology of many cases remains uncertain.

Every presentation of megarectum is suspicious of mechanical obstruction in the distal bowel and should be investigated by endoscopy to exclude an inflammatory or neoplastic stenosis.

Far more common than megacolon, many patients with chronic constipation have a long (undilated), tortuous colon. This so called “redundant colon” does not have clear pathological importance except when complicated by sigmoid or cecal (rare) volvulus.

Treatment and Management of Constipation

References

- Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:1360–8.

- Lennard-Jones JE. Constipation. In: Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology/Diagnosis/ Management editors Mark Feldmann, Scharschmidt J, Sleisenger MH. 7th ed. 2002; 1181.

- Rao SS. Constipation: evaluation and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2003; 32:659–83.

- Rao SS. Dyssynergic defecation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2001; 30:97–114.

- Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine AJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999; 45: (Suppl 2) II–43–47.