Table of Contents

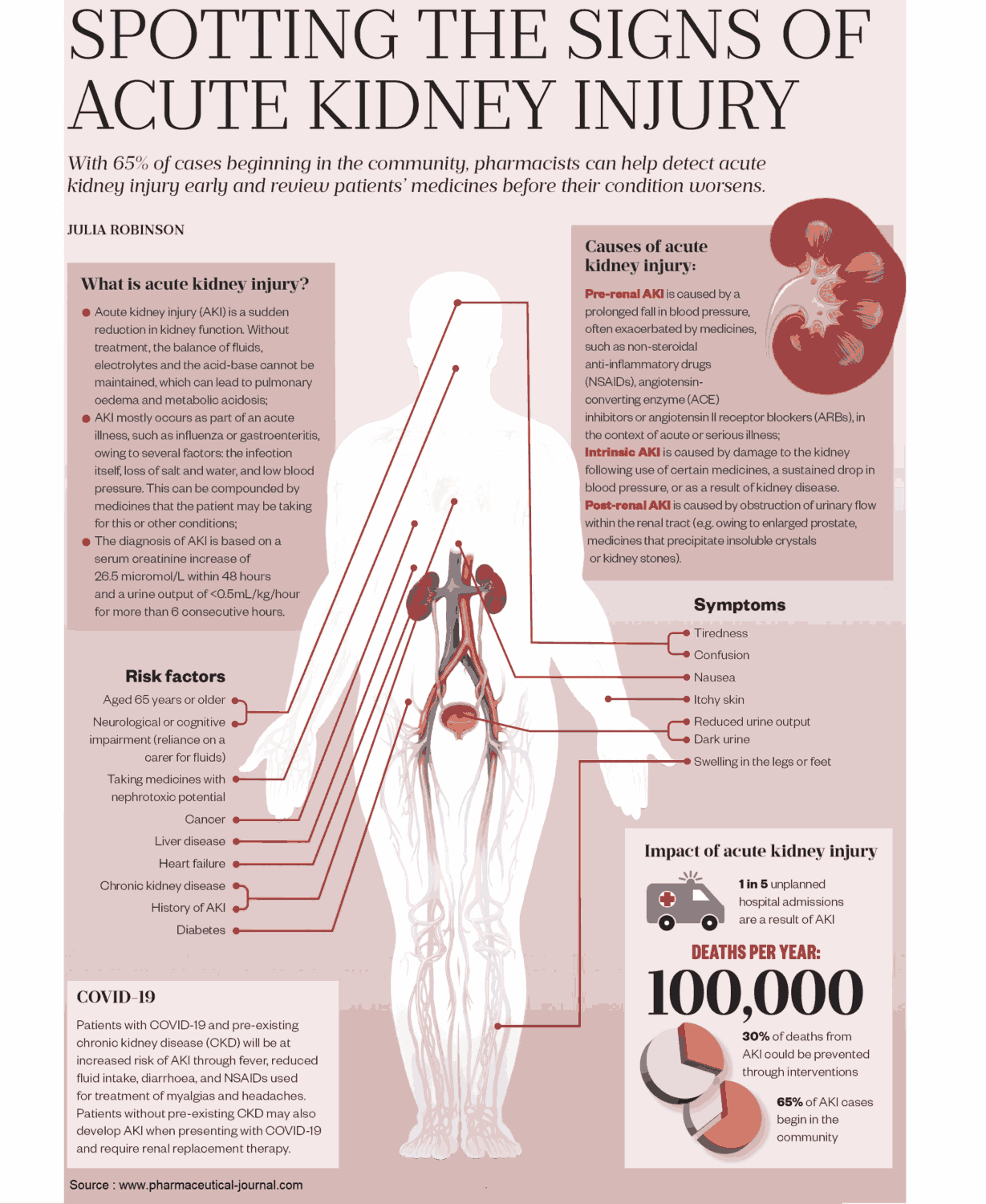

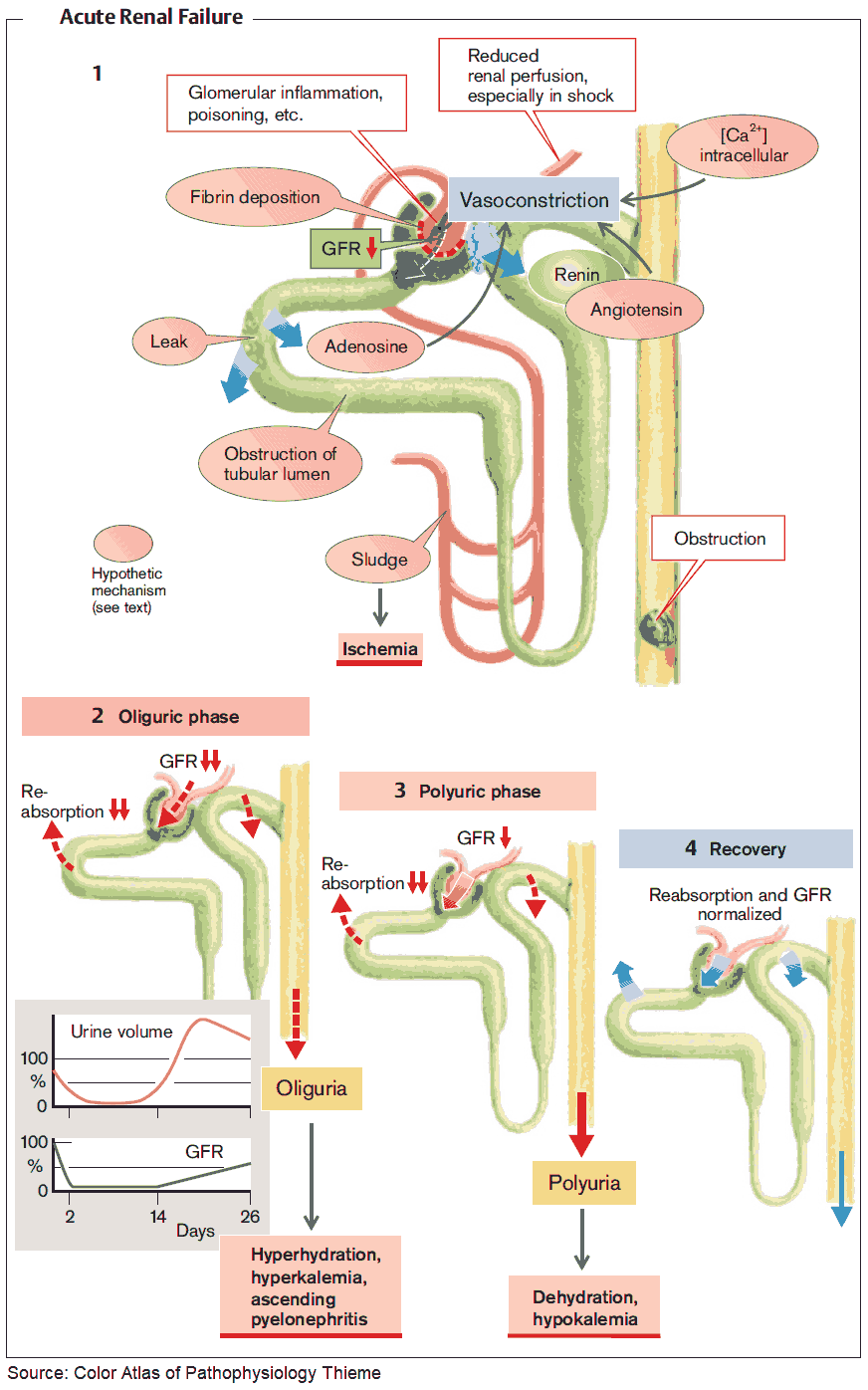

Acute kidney failure is a rapid decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) sufficient to cause uremia. Oliguria (below 15 mL per hour) is often a feature, although nonoliguric kidney failure can also occur, particularly in patients with severe burns, nephrotoxic damage, or oliguric kidney failure that has been converted to nonoliguric kidney failure by aggressive management with fluids, diuretics, and other agents.

Remember that a doubling of the creatinine is the result of loss of 50% of renal function. Therefore, if a patient who has a baseline creatinine of 0.4 mg/dL comes to the hospital with a creatinine of 1.0 mg/dL (still within normal limits), the patient is in renal failure. This situation arises in the elderly, who, because of loss of muscle mass have very low creatinine at baseline. Always check old lab values to determine baseline when they are available.

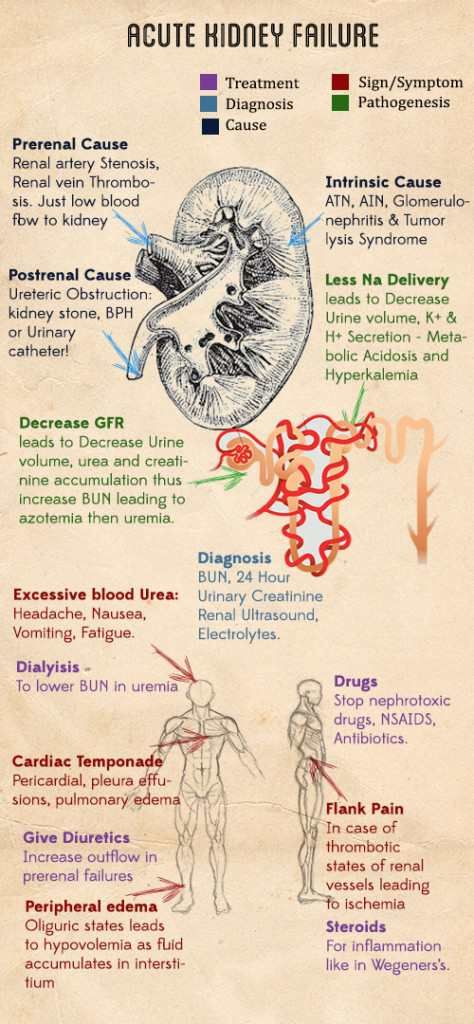

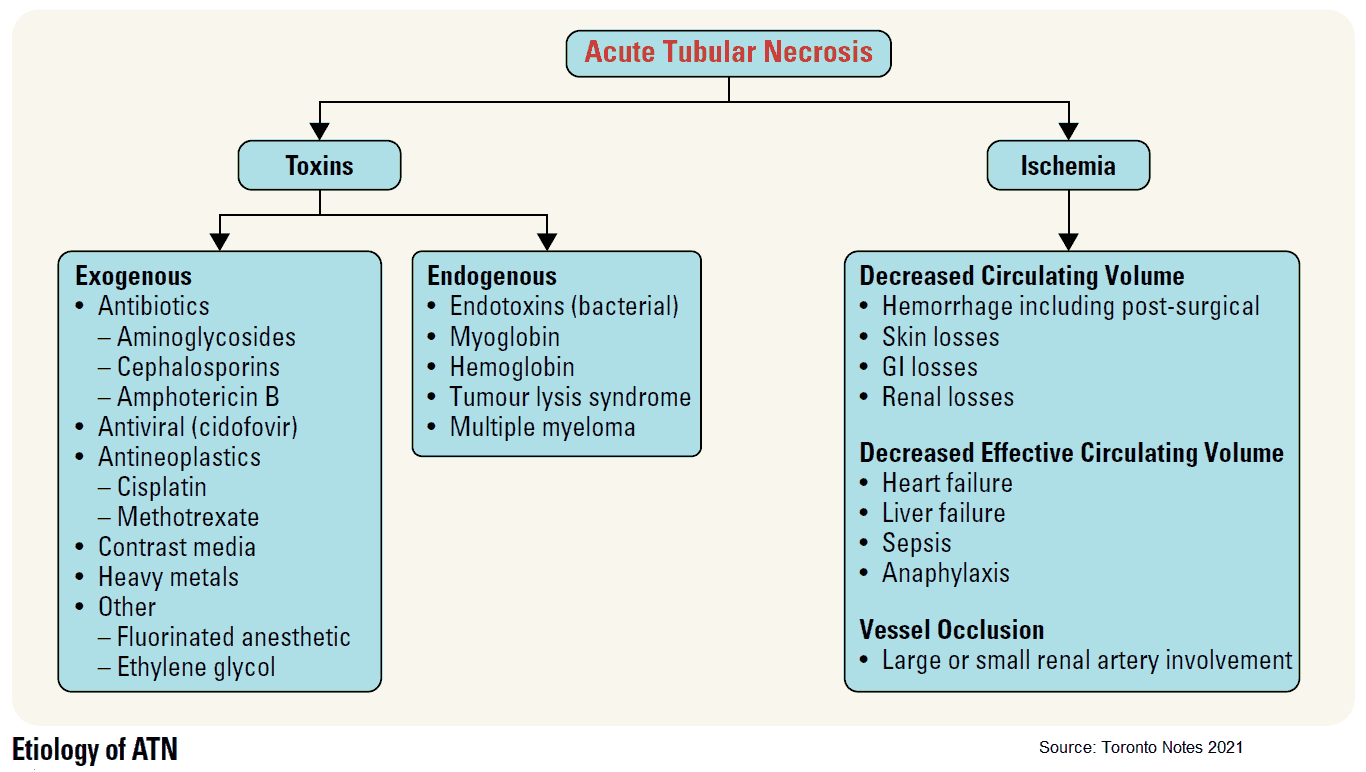

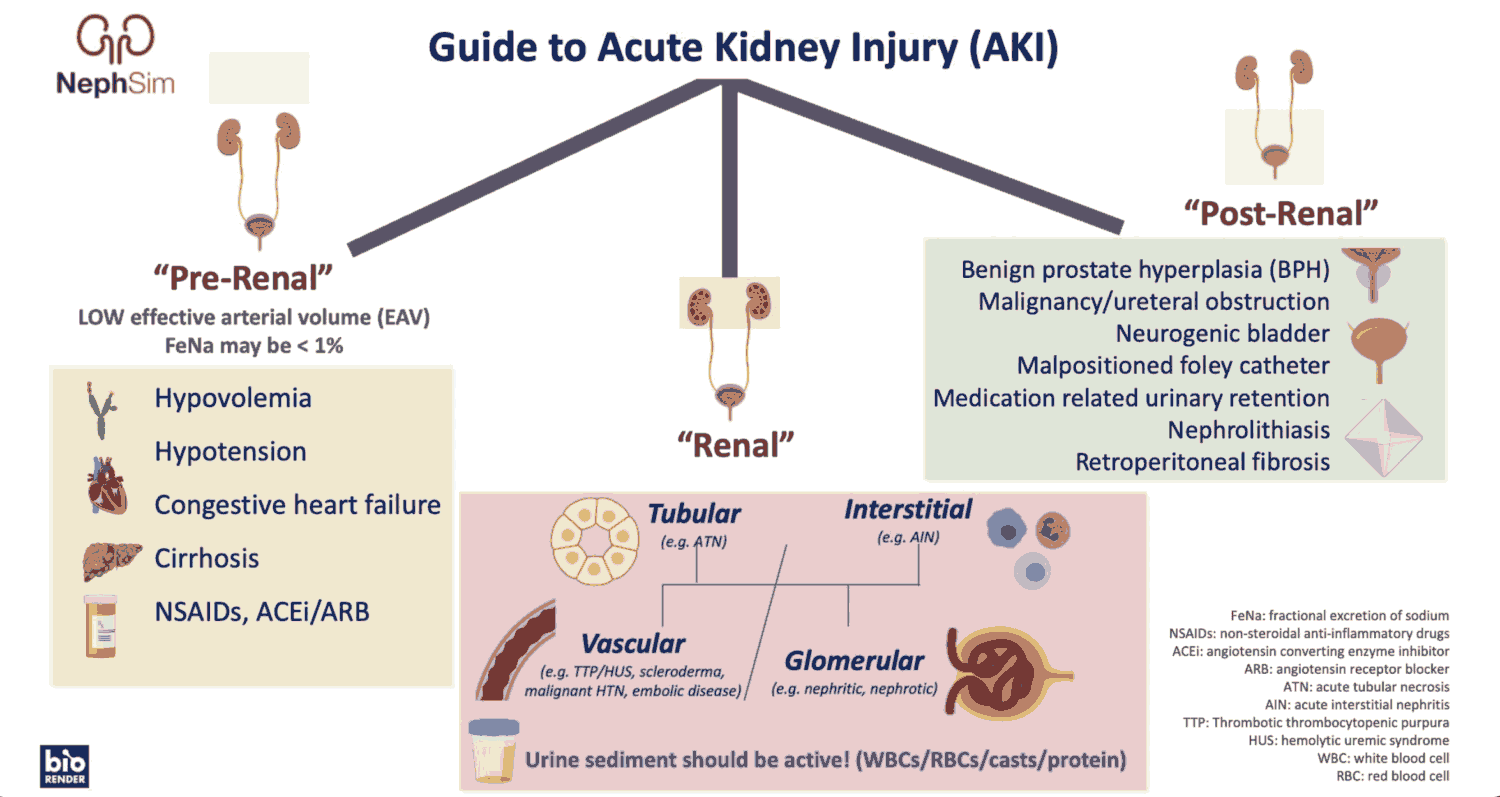

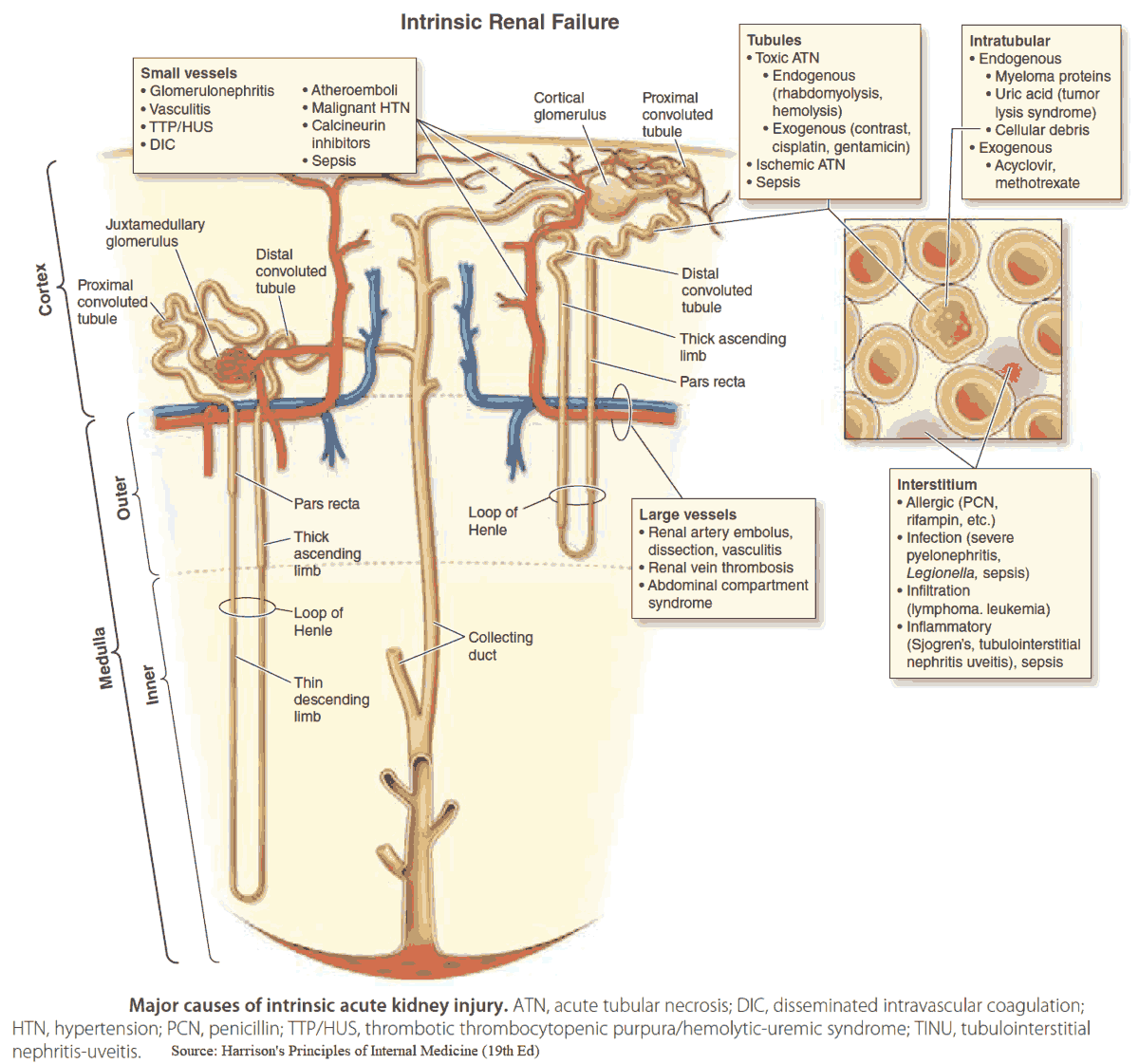

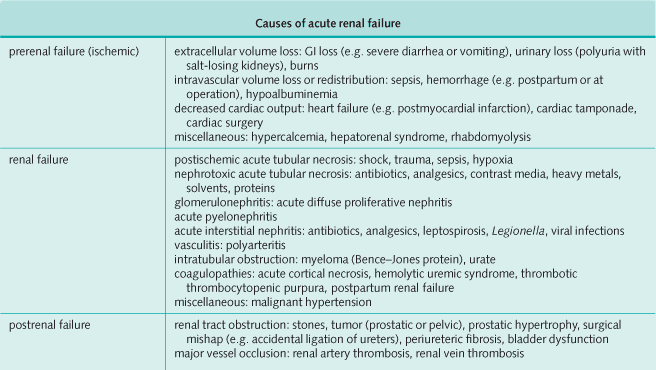

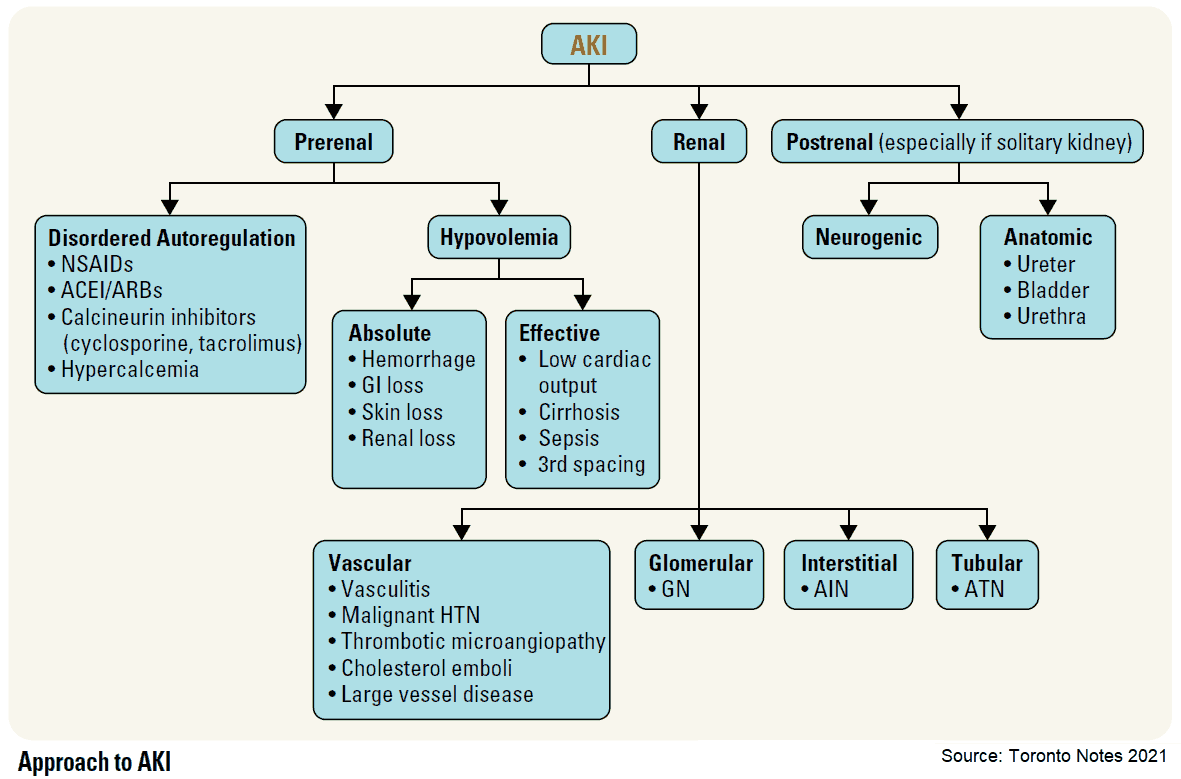

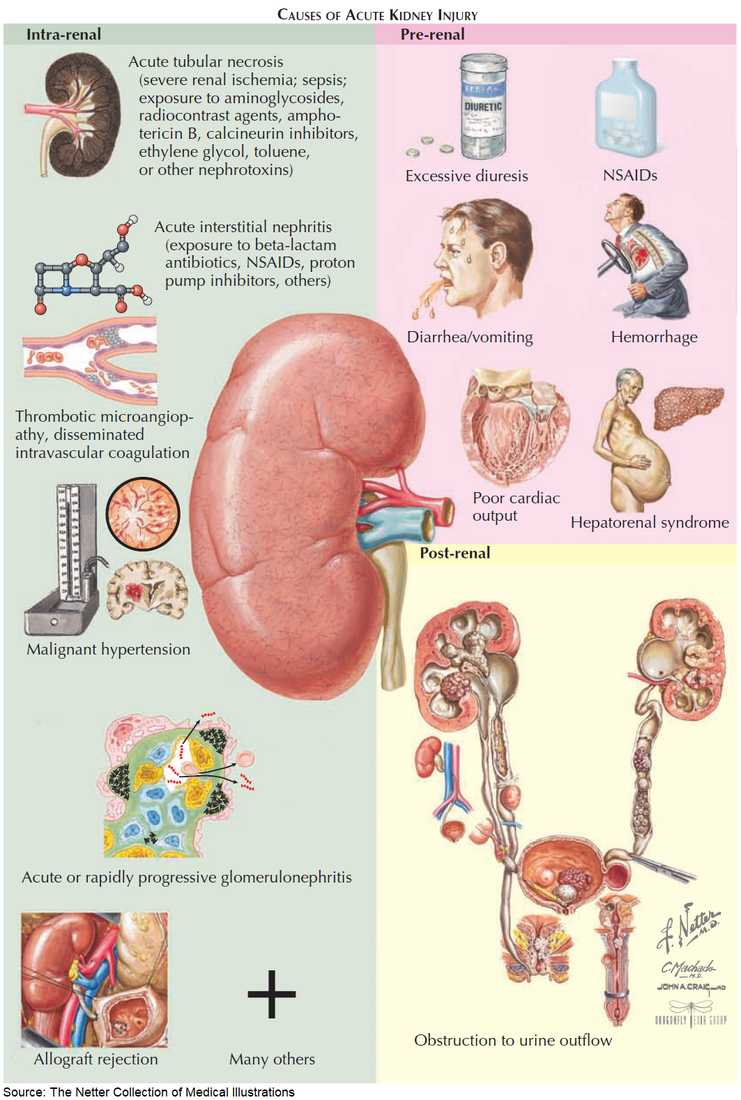

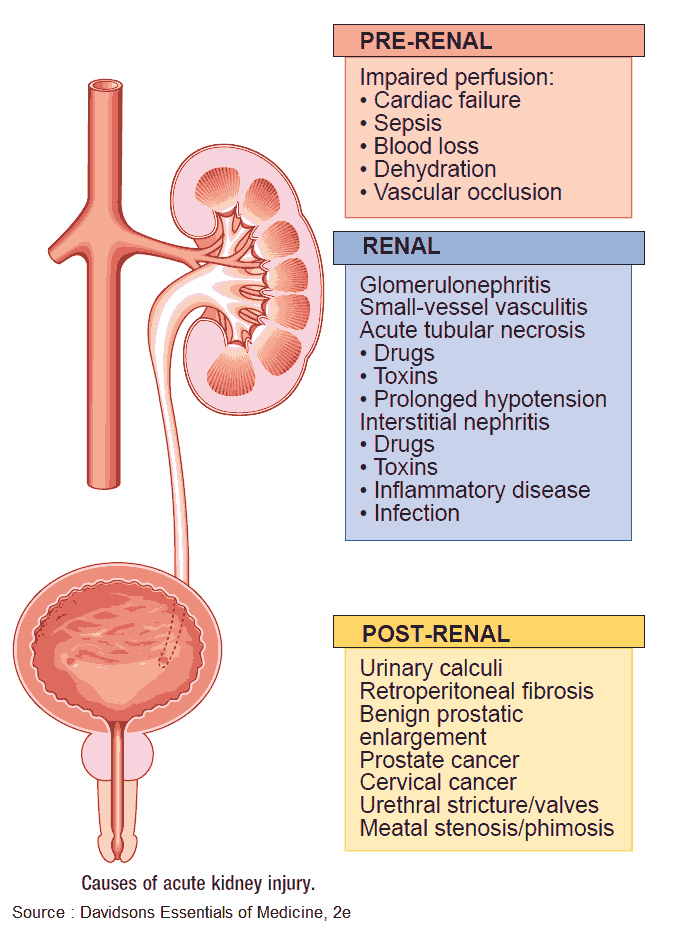

Etiology of Acute Kidney Failure

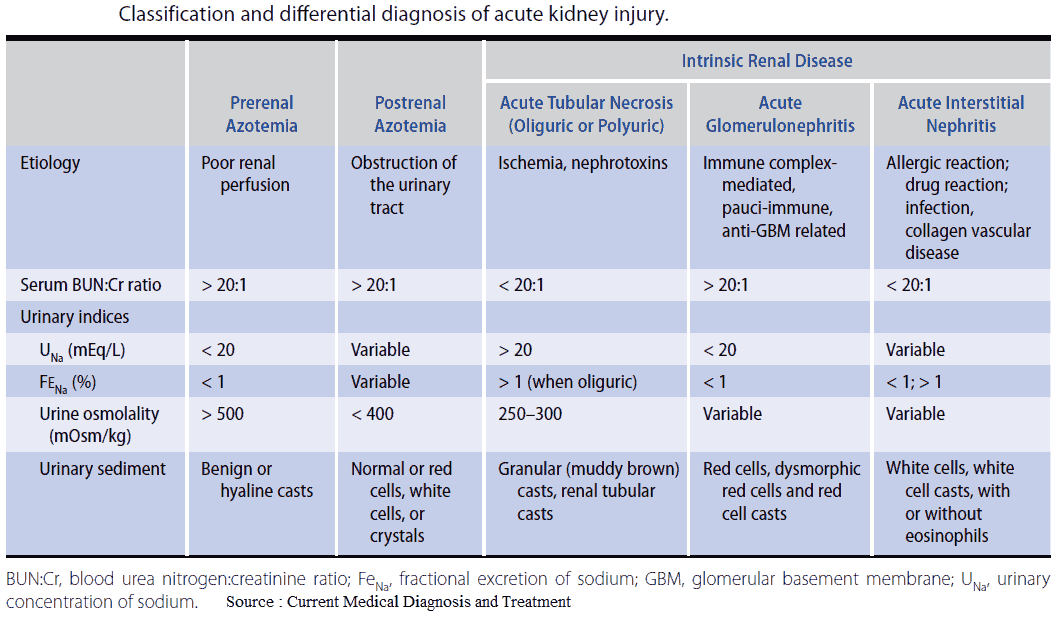

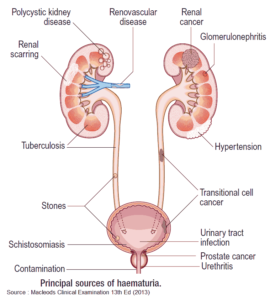

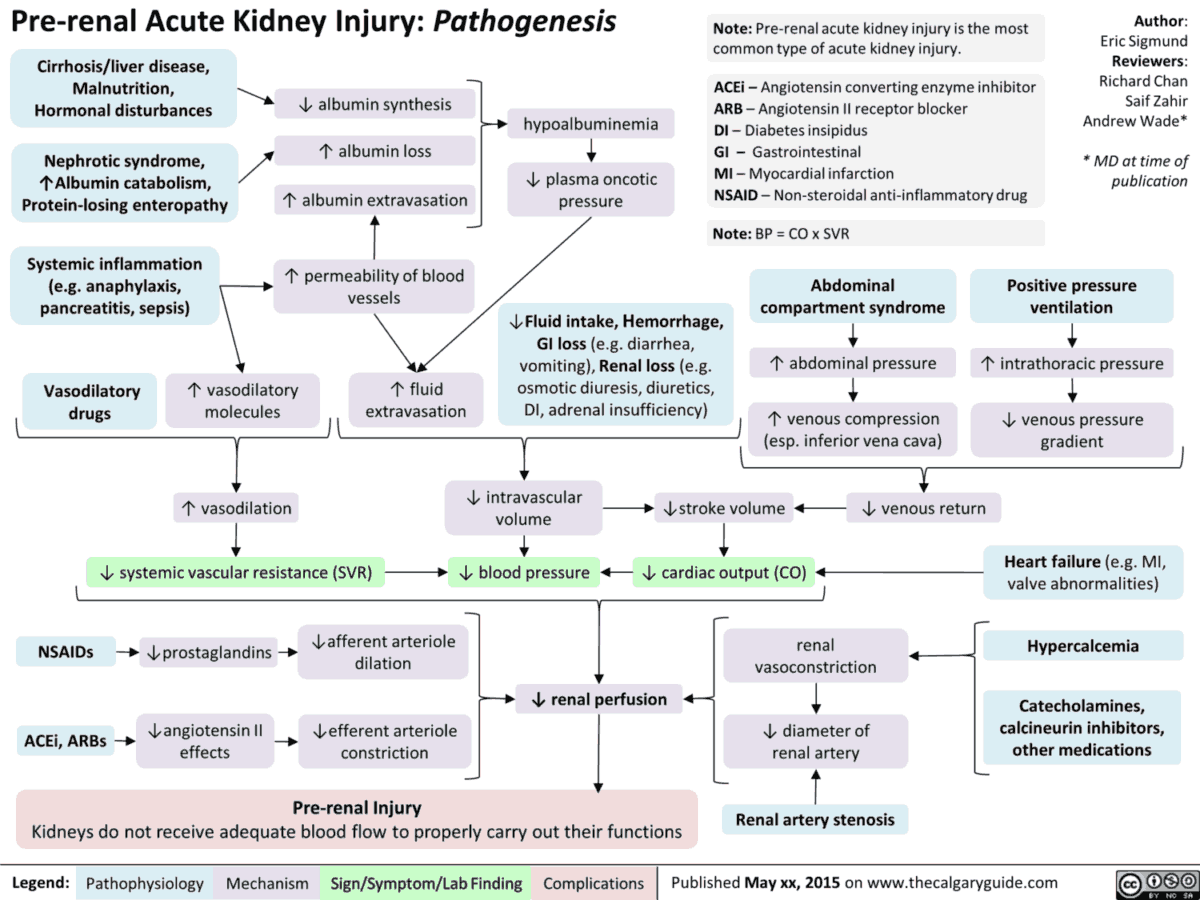

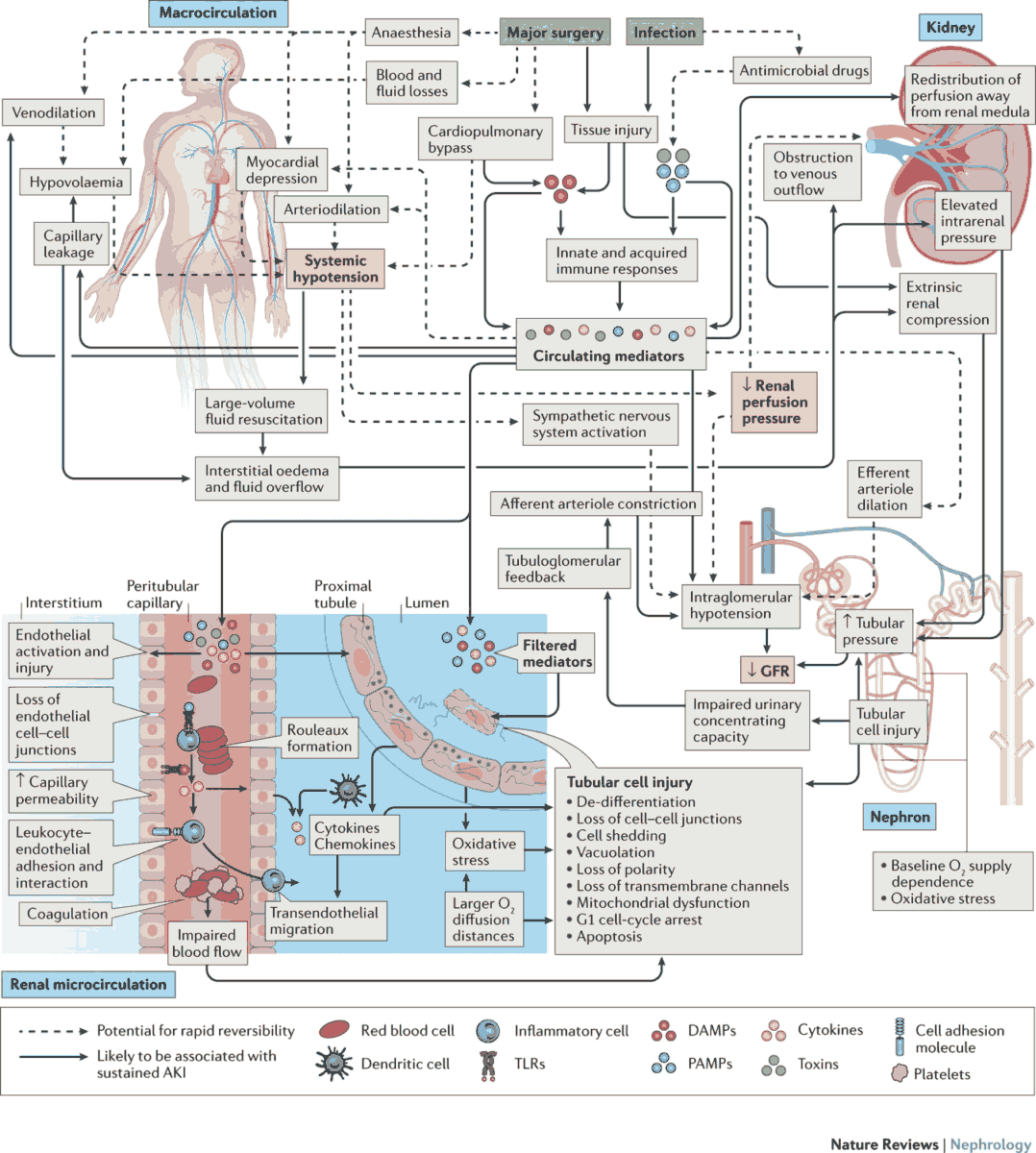

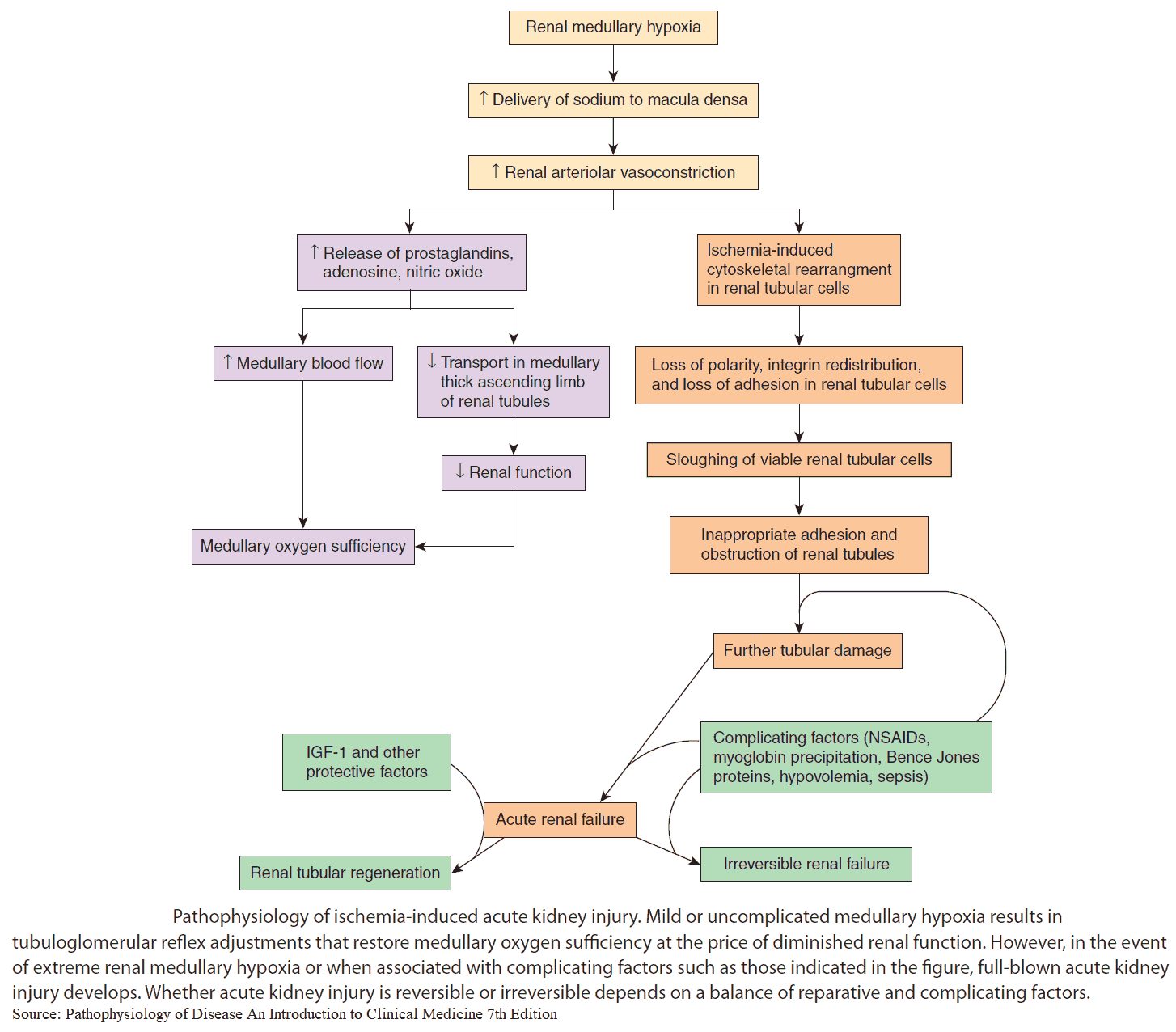

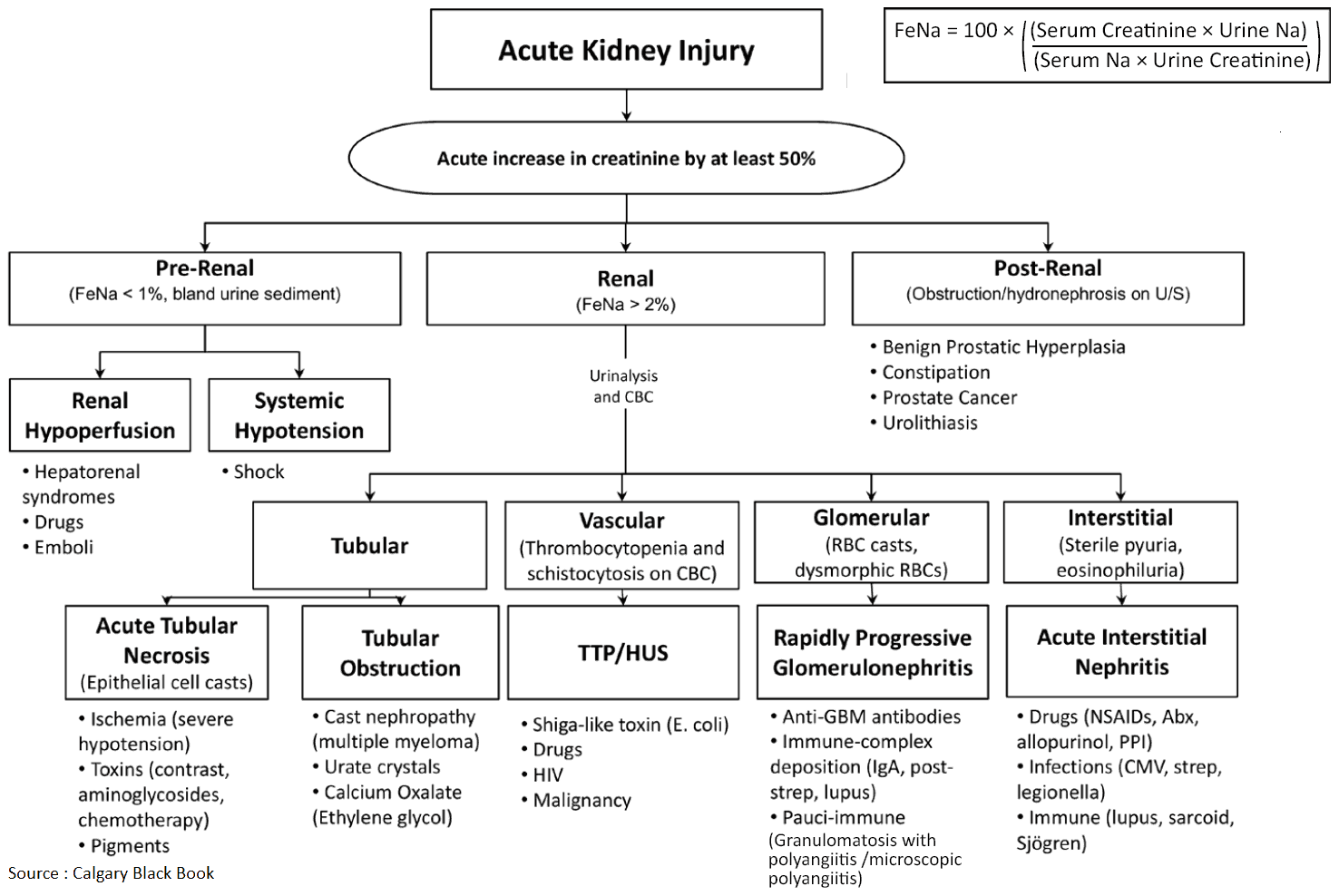

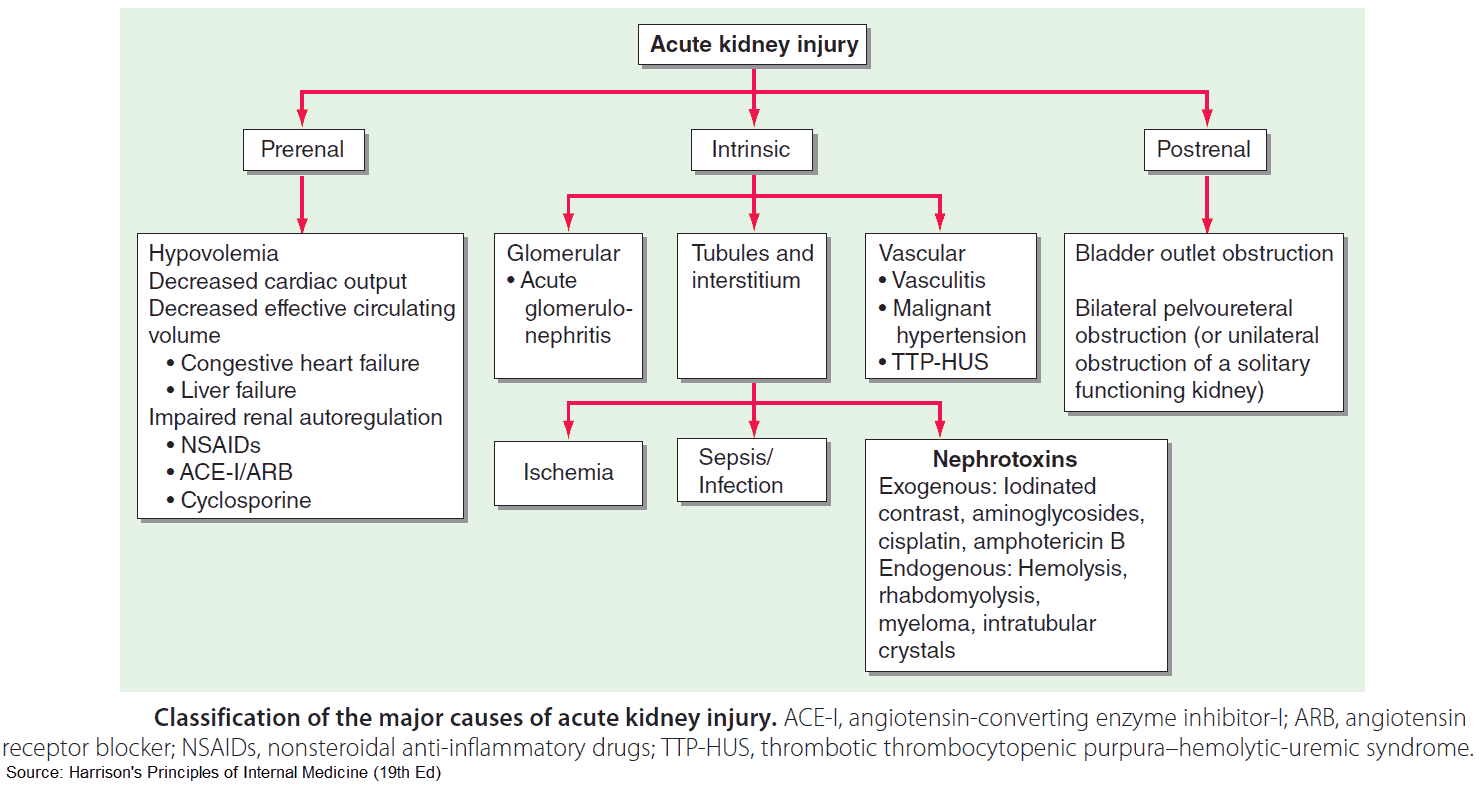

It is useful to classify ARF into prerenal, renal, and postrenal causes (see pictures below). However, the etiology is often multifactorial. For example, in postsurgical ARF, fluid depletion, systemic infection, and nephrotoxic drugs may all play a role. ARF may also complicate chronic renal failure.

Clinical Features of Acute Kidney Failure

The clinical features depend on whether there is pre-existing chronic renal impairment and whether the cause is pre-, renal-, or post-renal failure. A full history should be taken, focusing on previous renal disease, a history of hypertension or analgesic abuse, symptoms of prostatism, recent diarrhea, vomiting or blood loss, and recent operations.

Symptoms of renal failure include:

- Thirst

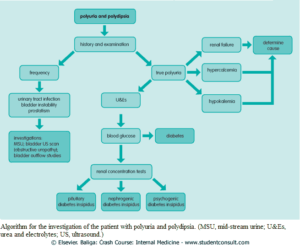

- Polyuria

- Nocturia

- Anorexia

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fatigue

- Itching

- Confusion

- Oliguria

- Dehydration

- Signs of volume overload (e.g., pulmonary edema and ankle or sacral edema) with nephrotic syndrome

- Signs of volume depletion (e.g., postural hypotension, a rapid small volume pulse, reduced tissue turgor)

The examination should focus on both the cause and consequences of the renal failure.

- The patient may have a yellow-brown pallor of uremia, and brown lines at the ends of the finger nails.

- If acidotic, there is deep sighing (Kussmaul’s) respiration.

- There may be palpable kidneys with polycystic kidney disease or hydronephrosis.

- There will be a palpable bladder with outflow obstruction.

- Pericarditis occurs in advanced uremia, and twitching, hiccoughs, and uremic frost also occur late.

- Check the blood pressure (are there other signs of malignant hypertension, and/or is there a postural drop suggesting volume depletion?) and look for bruising.

- Perform a rectal examination for prostatic hypertrophy or carcinoma, and a vaginal examination for pelvic masses.

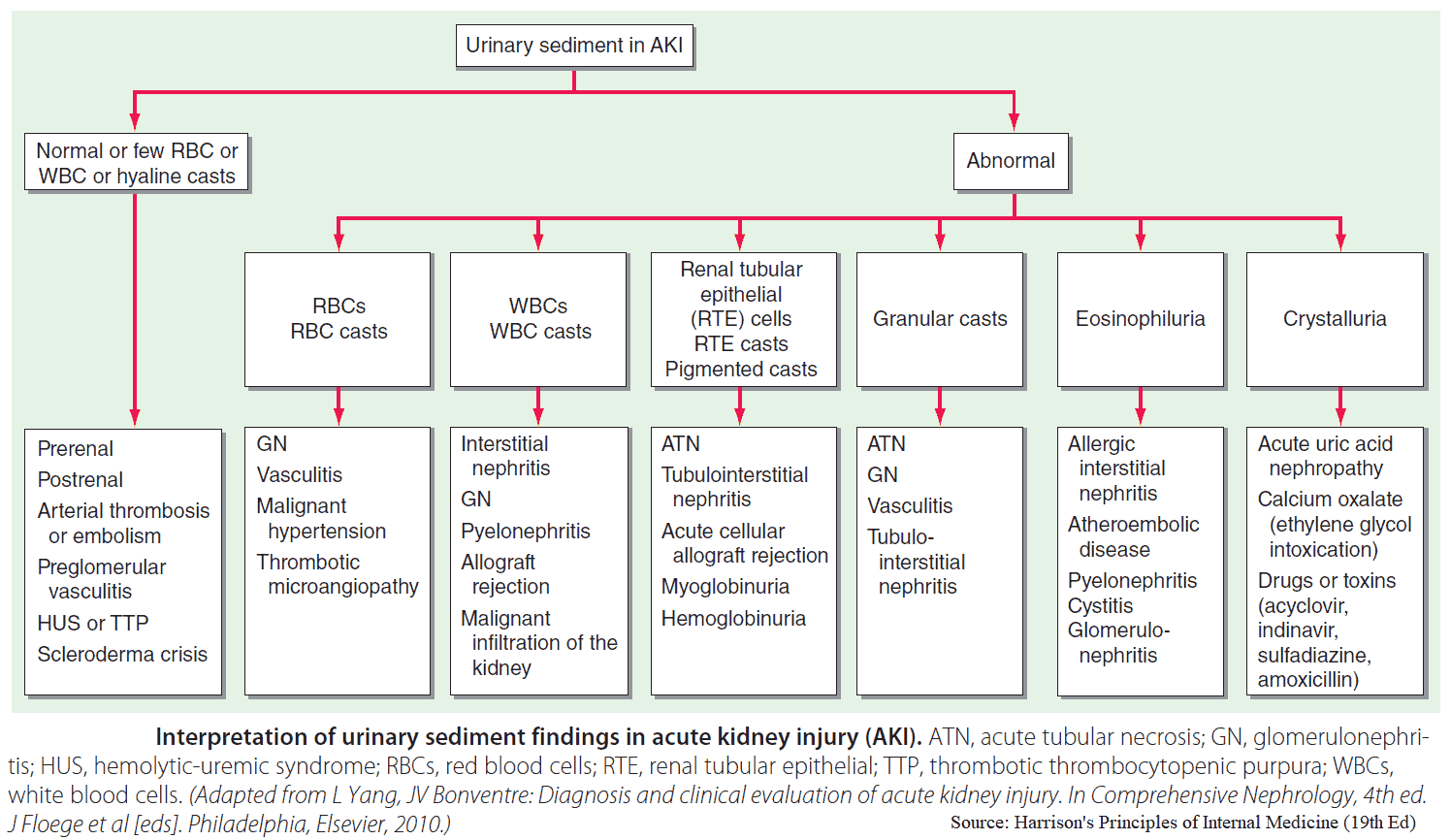

Investigations in Acute Kidney Failure

Urea, creatinine, and electrolytes should be assessed, in addition to strict recording of fluid intake and output. This will confirm renal impairment and serve as a useful baseline for monitoring the patient’s progress. If the patient is acidotic, serum bicarbonate will be low. It is crucial to check the potassium as hyperkalemia can be life-threatening, and immediate measures to lower the potassium need to be taken.

Urine should be sent for microscopy, culture, and sensitivity. In patients with acute tubular necrosis there will be casts, whereas these are absent in prerenal failure.

Patients with established acute tubular necrosis cannot concentrate the urine or conserve sodium. Consequently urinary sodium is usually over 20 mEq/L; the urine is dilute (osmolality below 310 mEq/L) with a urine/plasma osmolality ratio below 1.1 : 1; and urinary urea is below 150 mEq/L with a urine/plasma urea ratio below 3 : 1. Conversely, in prerenal failure, urinary sodium is below 20 mEq/L; the urine is concentrated (osmolality over 450 mEq/L) with a urine/plasma osmolality ratio over 1.5 : 1; and urinary urea is over 330 mEq/L with a urine/plasma urea ratio over 8 : 1.

In prerenal failure the serum BUN to creatinine ratio is also increased. During times of intravascular hypovolemia, the kidney preferentially retains urea to increase the osmotic load to which the loop of Henle is exposed. By increasing the urea concentration, more water is pulled out of the loop of Henle as it dips toward the renal medulla. This allows the body to conserve more water and alleviates the hypovolemia. Prerenal states can lead to a BUN/creatinine ratio >30 : 1.

In addition, the following investigations are important in the patient with Acute Renal Failure:

- Complete blood count: a normochromic normocytic anemia suggests pre-existing chronic renal impairment.

- Coagulation panel for coagulopathies.

- Urine for Bence-Jones protein; serum immunoglobulins and electrophoresis.

- Blood cultures to look for infection.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) for the precipitating cause (e.g., myocardial infarction) or complications such as pericarditis or hyperkalemia.

- Abdominal x-ray: look for renal size; normal kidneys are 13 ± 2 cm; small kidneys suggest pre-existing renal disease; the kidneys may be large in polycystic disease; stones in the renal tract may be visible.

- Abdominal ultrasound will demonstrate kidney size, as well as stones and dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system in outflow obstruction.

- Isotope renography will demonstrate kidney function.

- CT scan, especially noncontrast, can be very helpful in evaluating kidney stones, renal cell carcinoma, cysts, and even renal vein thrombosis.

- Renal biopsy should be performed in patients to confirm the diagnosis of glomerulonephritis or vasculitis. The biopsy can help direct treatment.

Management of Acute Kidney Failure

Immediate thoughts should be to correct hypovolemia, exclude obstruction, and assess the presence of previous intrinsic renal disease.

Fluids should be replaced and electrolytes should be corrected quickly. Monitoring with a central venous pressure line is essential for proper assessment of fluid balance.

Appropriate antibiotics should be given for septicemia or other infections. Bilateral nephrostomy tubes will relieve obstruction. Surgery can then be performed later.

If there is established acute tubular acidosis, intravenous fluids may still be needed. Vasoactive agents (e.g., dopamine and dobutamine) may be necessary to achieve a blood pressure which is appropriate for the patient’s age and history. Correction of hypoxia and acidosis may also improve cardiac and renal function.

If oliguria persists after adequate circulation is established, or if the patient has established renal failure and is volume overloaded, intravenous furosemide should be given, either as slow boluses or as an intravenous infusion. Strict fluid balance should be kept with daily weights and regular assessment of fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional requirements. In general, patients should be given 500 ml of fluid per 24 hours as well as the volume of urine output from the previous 24 hours. In patients with fluid retention a weight loss of 0-1 kg per day should be aimed for.

Note, however, that fluid overload may occur in patients without any change in weight, as negative nutritional balance may cause a loss of 1-2 kg per day. Careful examination is necessary to detect fluid accumulation, which should be counteracted by further sodium and water restriction.

Patients should be on a low-protein, high-carbohydrate diet. In many cases, the patient’s appetite is poor and calorie supplements may be required.

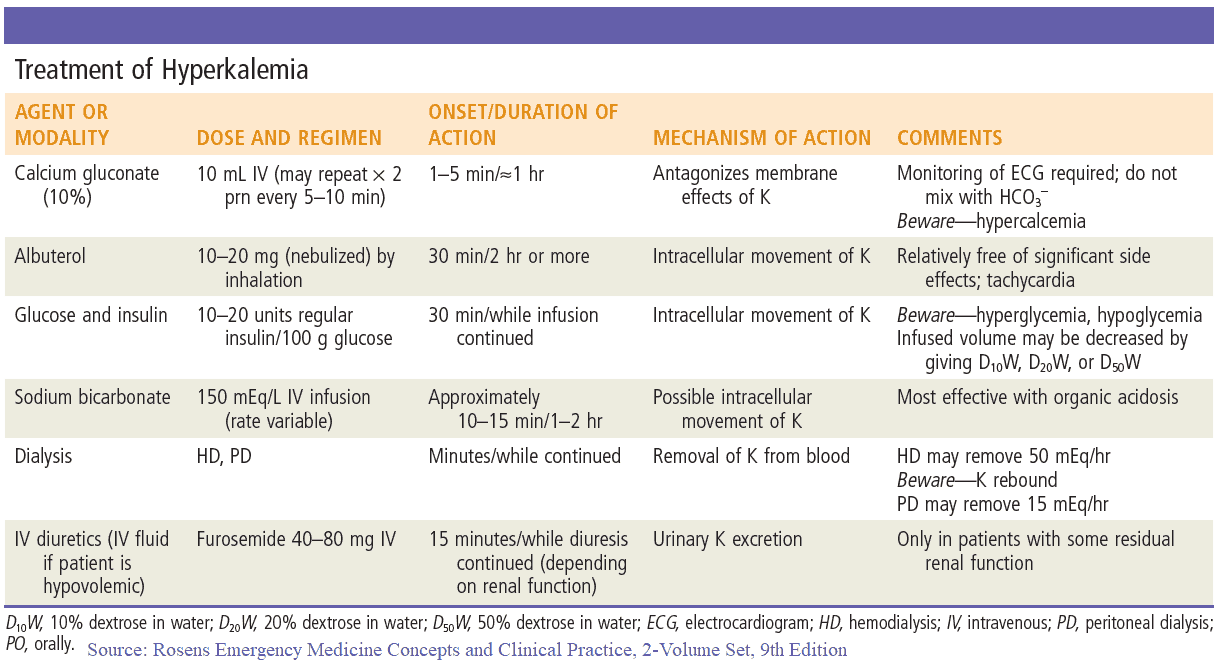

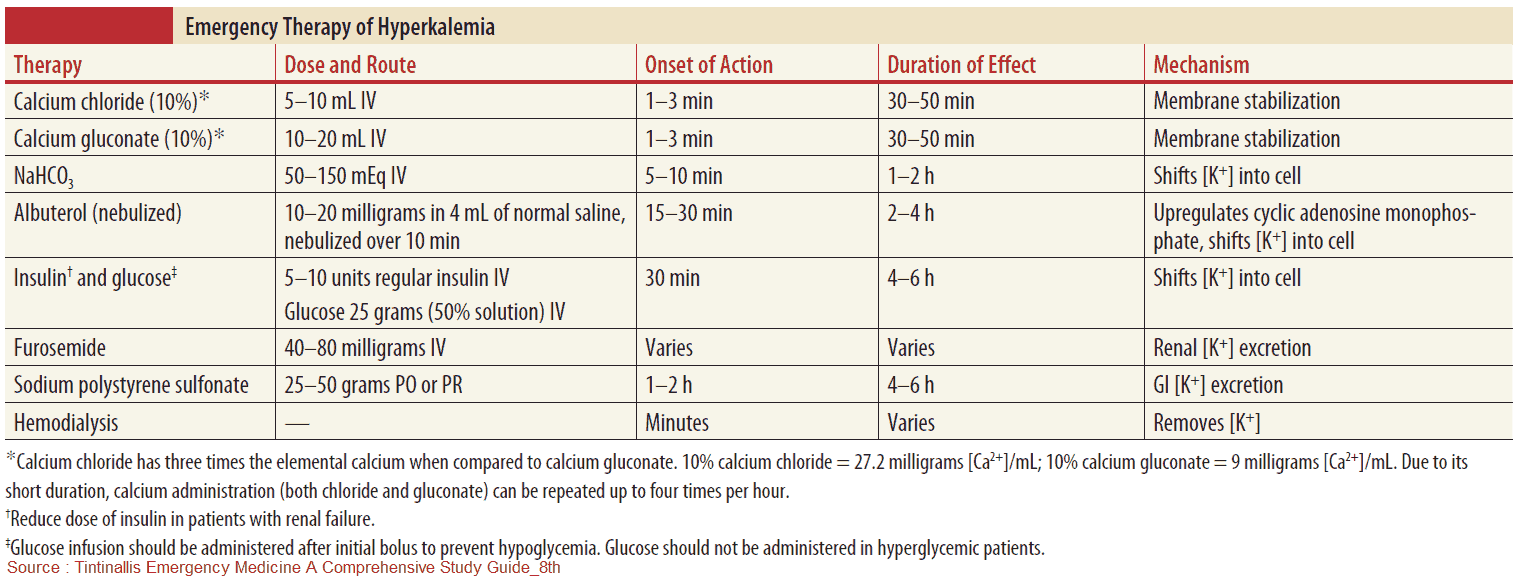

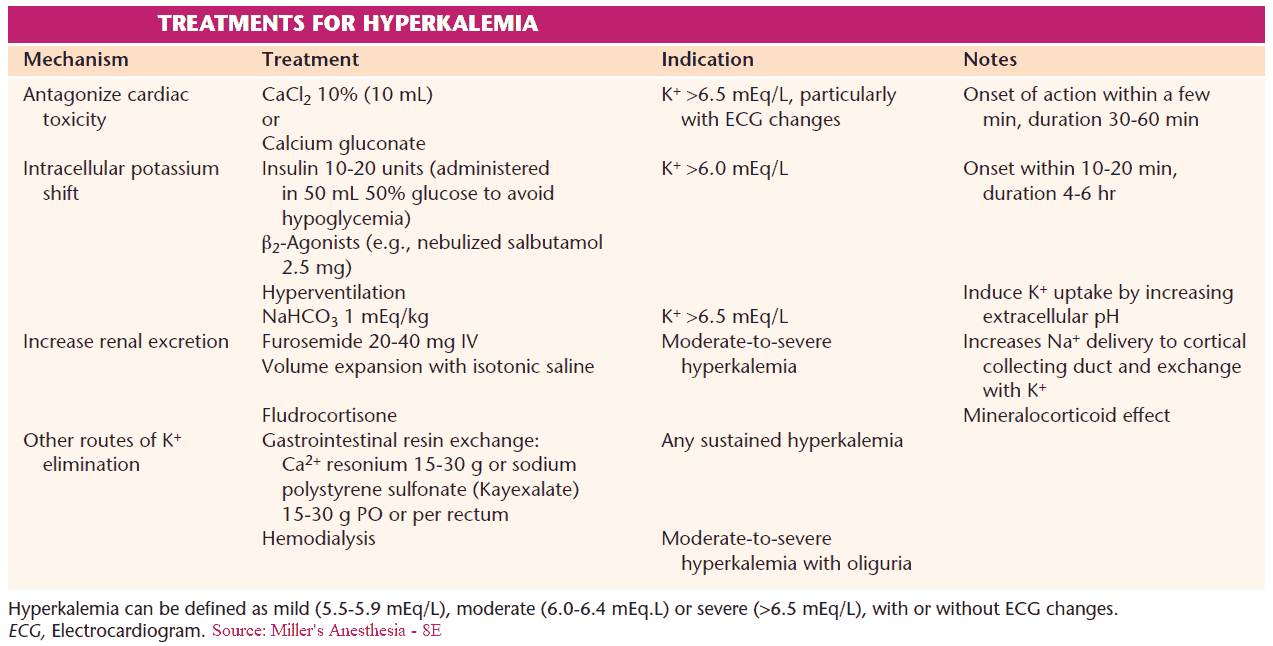

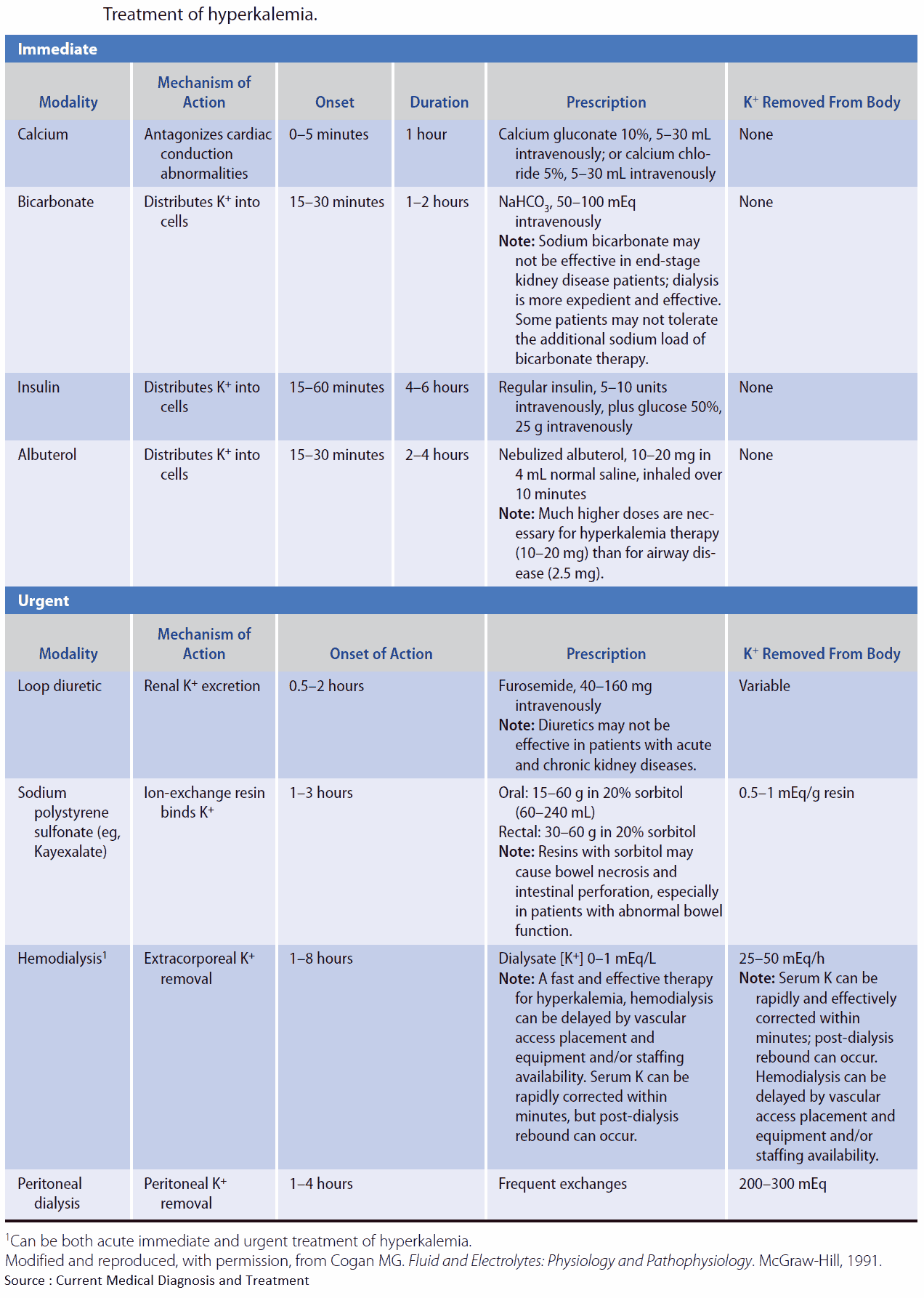

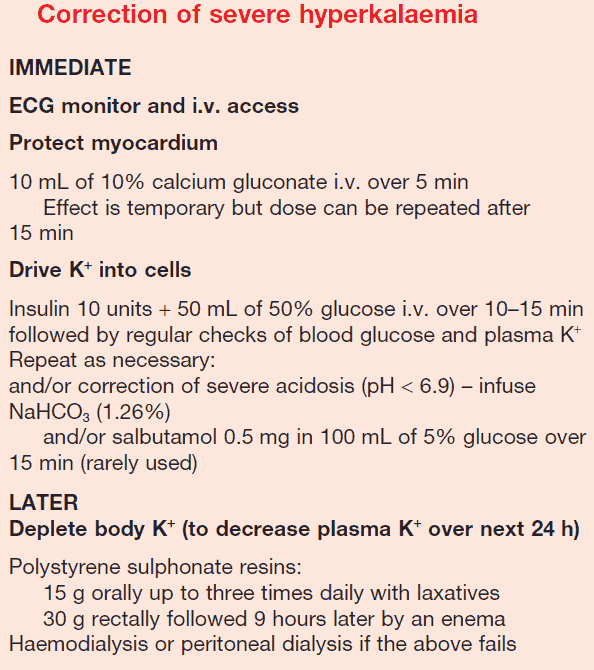

Treatment of Hyperkalemia

Because this may be life-threatening, reduction of potassium should be the top priority if it is above 7 mEq/L, particularly if ECG changes are present. These ECG changes can be reversed temporarily by boluses of 10 ml of 10% calcium gluconate solution. The patient should also be on a cardiac monitor.

Potassium should be redistributed intracellularly by the correction of acidosis with sodium bicarbonate 100-150 mmol/L and the administration of glucose 50-100 mg. Insulin may be necessary to control hyperglycemia. It is usually necessary to give these drugs in small volumes in order to avoid fluid overload. Polystyrene sulphonate resin (Kayexalate), 20 g 6 hourly orally, or as an enema (30 g), will maintain a low potassium.

Do not give calcium chloride IV through the same canula as sodium bicarbonate-it forms chalk!

Indications for dialysis in kidney failure

Indications for dialysis in renal failure are as follows:

- Persistent hyperkalemia (e.g., serum potassium above 6.5 mEq/L)

- Severe acidosis (e.g., bicarbonate below 15 mEq/L)

- Symptomatic uremia (e.g., confusion and hiccoughs)

- Pericarditis

- Pulmonary edema or progressive fluid retention

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with ARF depends on the cause. Patients with nonoliguric ARF have a lower mortality rate. A particularly high mortality rate is found in older patients and those who have severe burns, severe pancreatitis, hepatorenal syndrome, intra-abdominal sepsis, pre-existing cardiovascular disease, or serious complications, such as pulmonary infection. Patients who recover generally return to health and independent living, and this justifies an aggressive approach to treatment.