Table of Contents

Hematuria and proteinuria are common presentations of renal disease, although both may also be due to systemic conditions.

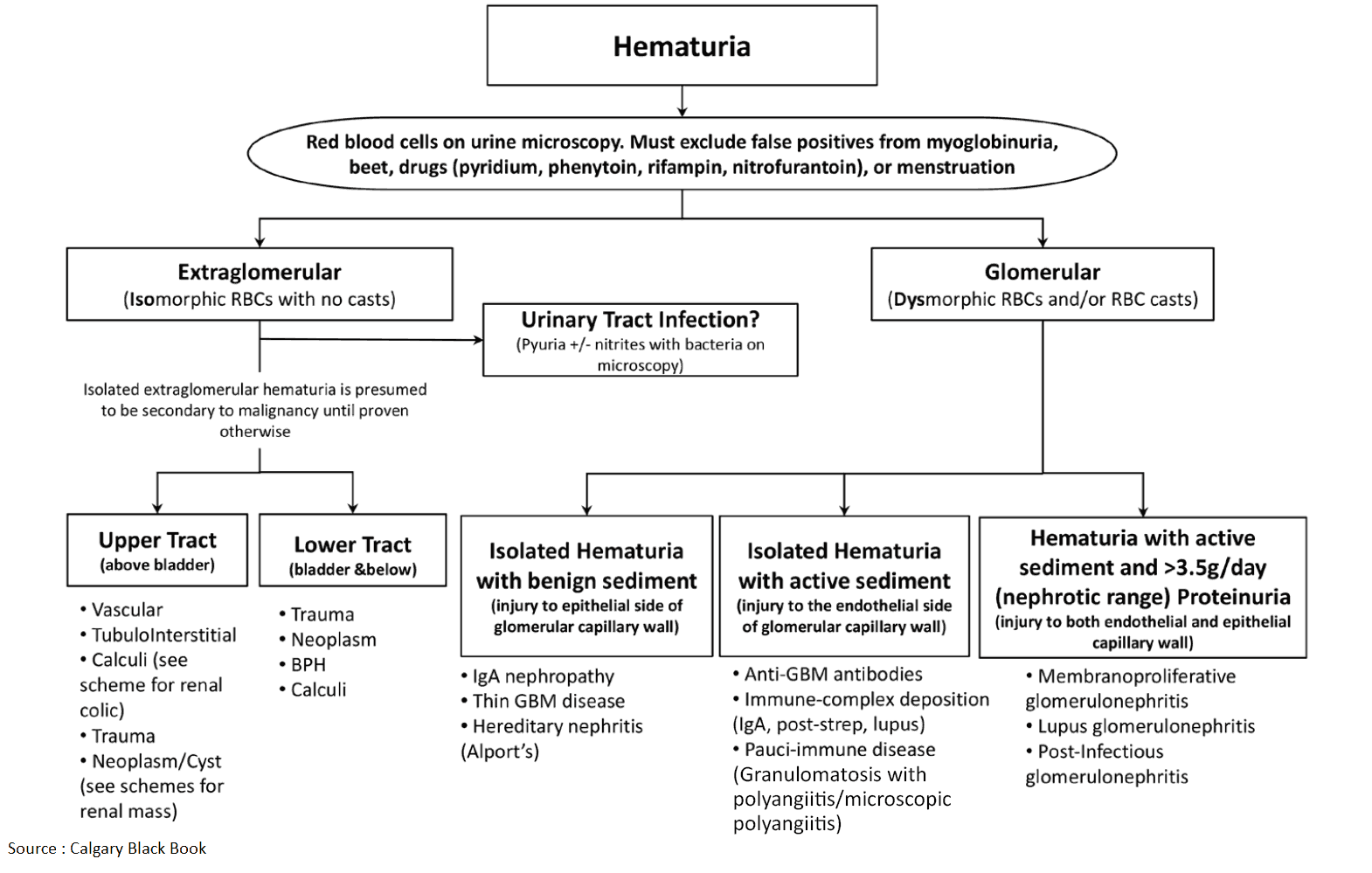

Hematuria is abnormal if there are more than 2 red blood cells per high-power field; proteinuria is defined as more than 150 mg of protein per 24-hour collection of urine. Red-colored urine may also be due to hemoglobinuria (hemolysis), porphyria, drugs (e.g., rifampicin), or even the ingestion of beets.

Patients need to be stratified by the quantity of hematuria, age, symptoms, past medical history, and family history in addition to whether proteinuria is also present. It is important to rule out life-threatening causes since urologic cancers are the cause of 5% of cases of microscopic hematuria.

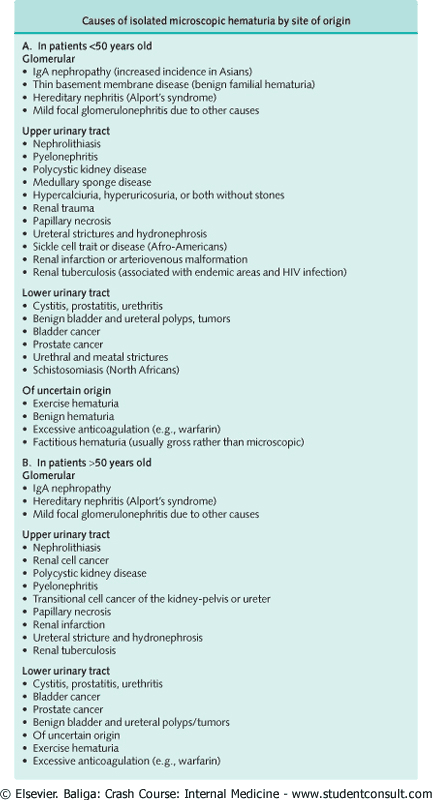

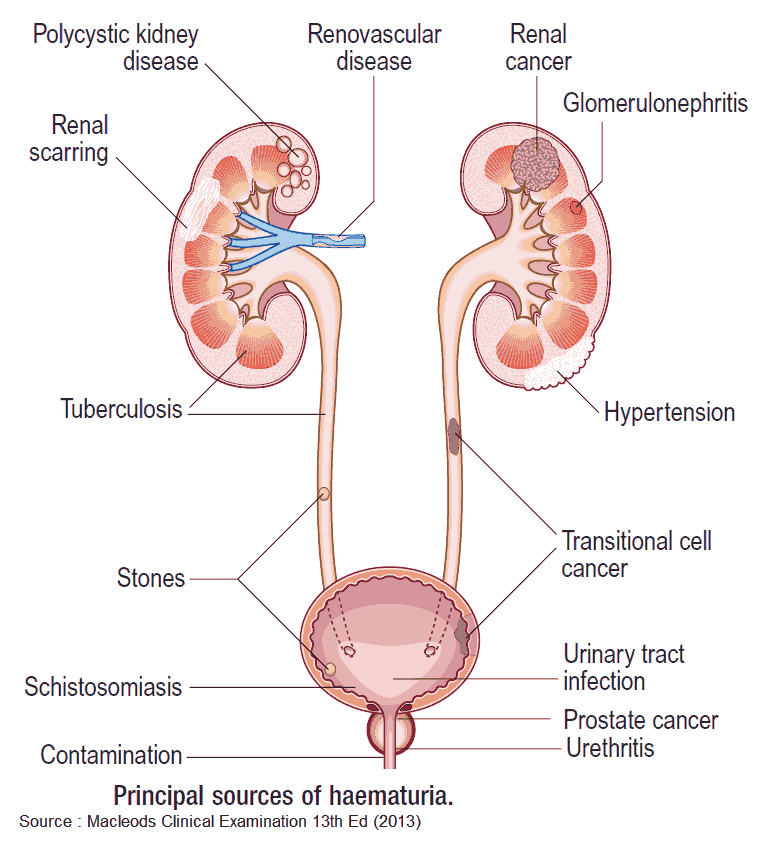

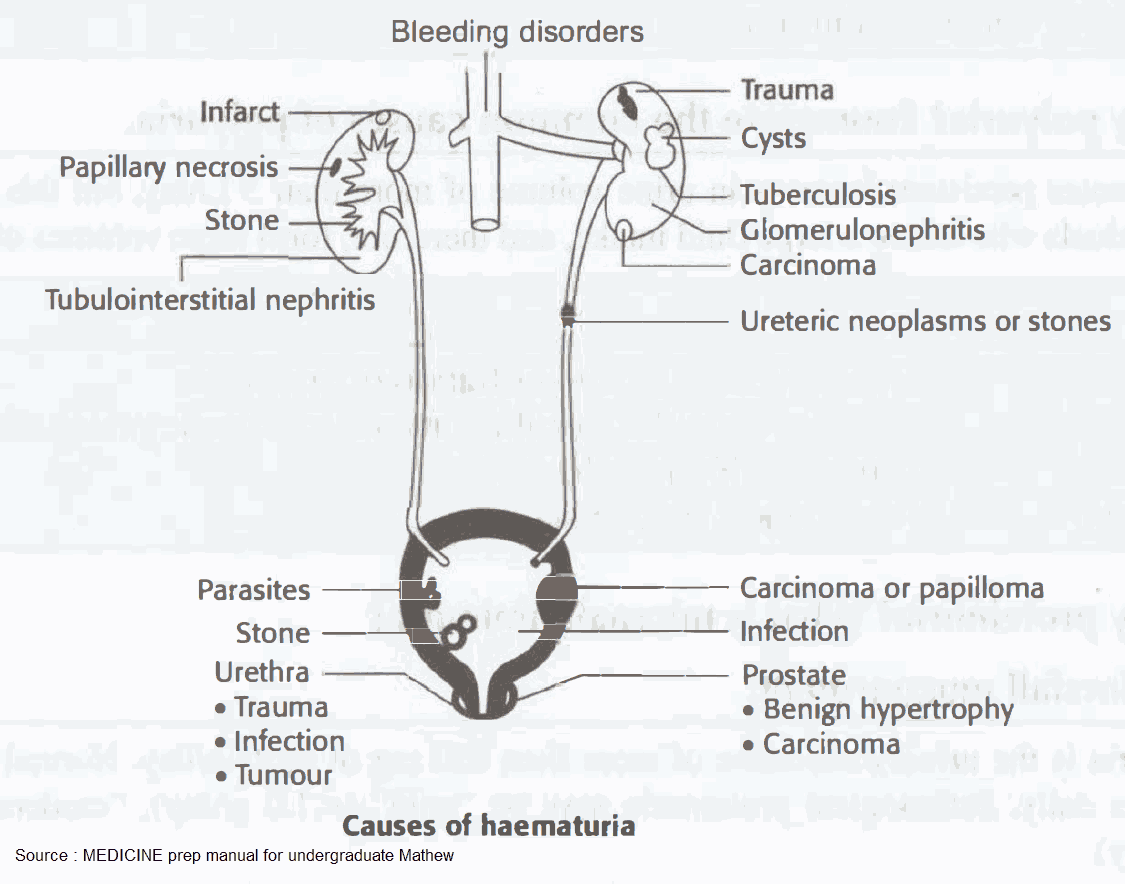

Differential Diagnosis of Hematuria

This is best classfied by the site of pathology.

Systemic conditions

- Clotting disorders and anticoagulants

- Thrombocytopenia

- Sickle cell disease

- Endocarditis

- Exercise-related

- Vasculitides

Kidneys/ureters

- Glomerulonephritis and its associated conditions (e.g., Hodgkin’s disease, subacute bacterial endocarditis, systematic lupus erythematosus, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Goodpasture’s syndrome). Infections (e.g., pyelonephritis, tuberculosis).

- IgA nephropathy.

- Alport’s syndrome.

- Benign familial hematuria.

- Tumors: carcinoma, nephroblastoma, angioma, adenoma, papilloma.

- Cystic disease: polycystic kidney disease, medullary sponge kidney.

- Sudden release of retained urine (e.g., after catheterization for urinary retention).

- Drugs (e.g., sulfonamides, warfarin).

- Hydronephrosis.

- Papillary necrosis.

- Hydatid disease.

Bladder/urethra

- Cystitis: infection, chemical-induced cystitis, postradiation cystitis

- Tumors: carcinoma, papilloma, hemangioma, sarcoma

- Trauma

- Calculi

- Infections: tuberculosis

- Foreign bodies (e.g., urinary catheters)

- Schistosomiasis

Prostate

- Prostatic carcinoma

- Tuberculosis

Other Sites

Hematuria may result from lesions in adjacent organs (by fistula formation or inflammation) such as:

- Colonic diverticulitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Acute appendicitis in a pelvic appendix

- Acute salpingitis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Carcinoma of the colon or genital tract

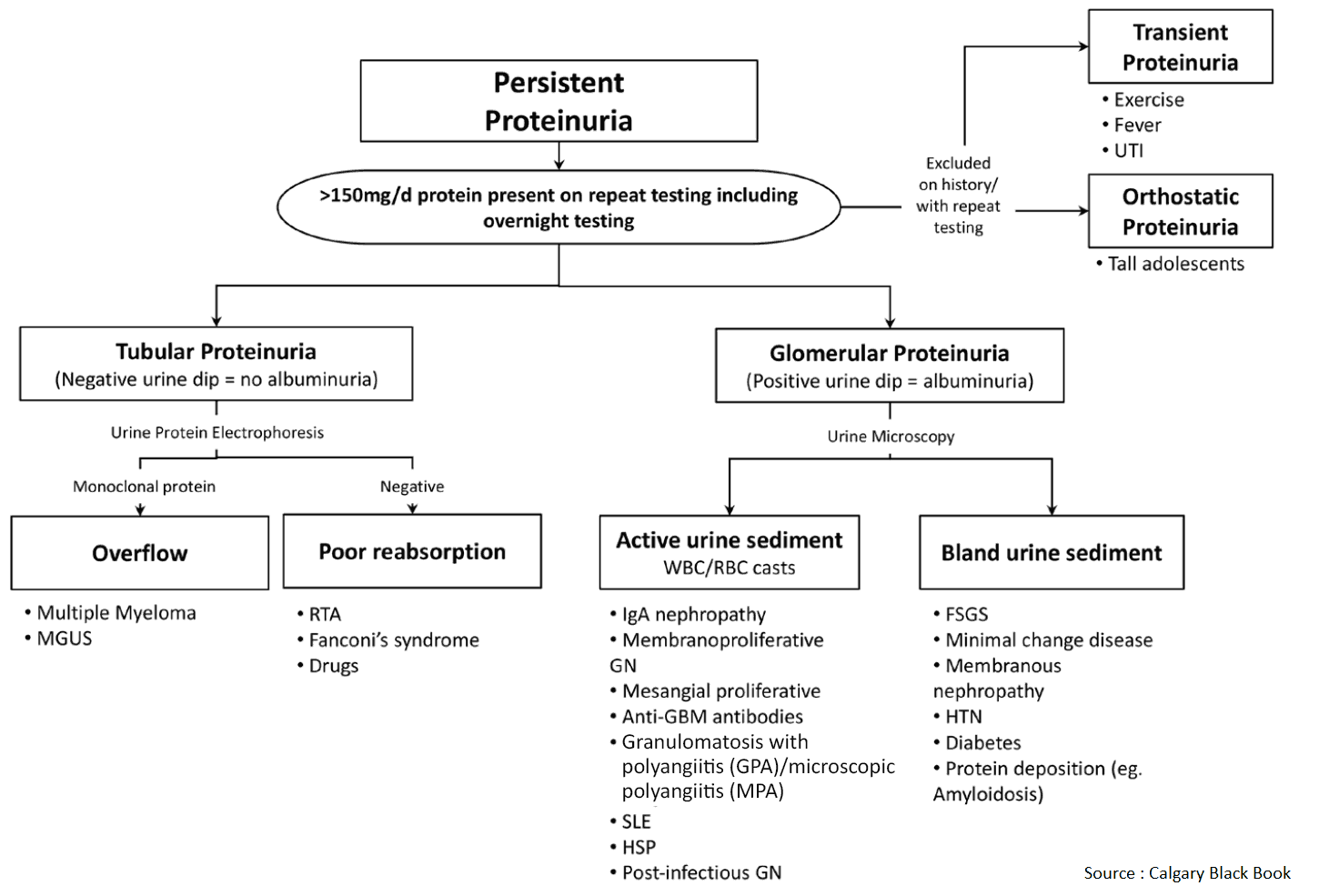

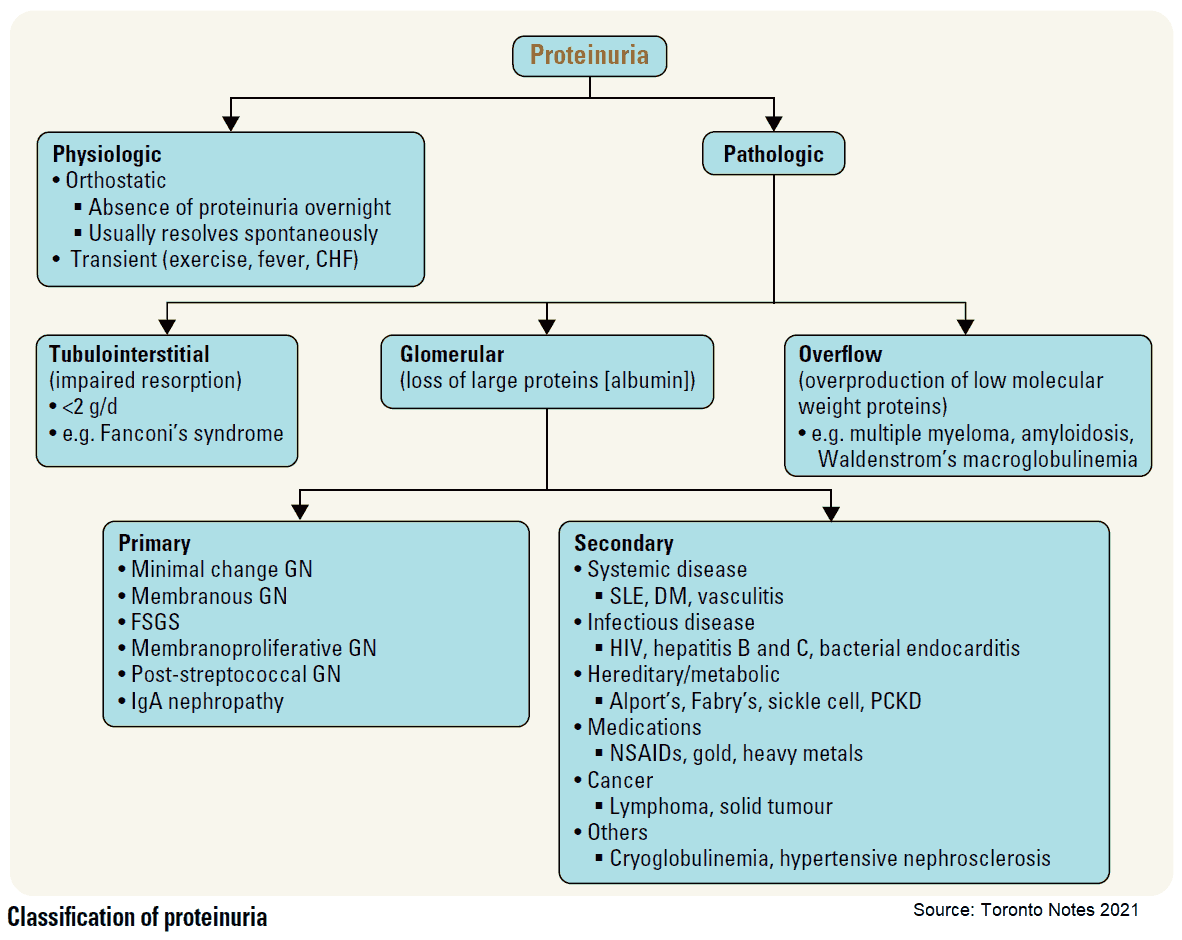

Differential Diagnosis of Proteinuria

Benign proteinuria may result from the following:

- Functional proteinuria: fever, strenuous exercise, congestive heart failure, acute medical illnesses, pregnancy.

- Idiopathic transient proteinuria: intermittent.

- Orthostatic proteinuria: common in patients under 30 years of age; significant proteinuria when upright but normal when supine.

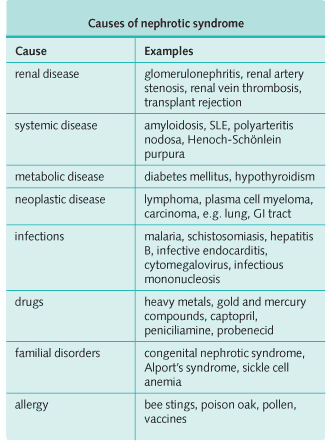

Other differential diagnoses of proteinuria include:

- Urinary tract infections.

- Vaginal mucus.

- Diabetes mellitus.

- Glomerulonephritis.

- Causes of nephrotic syndrome.

- Myeloma: Bence Jones protein in urine (light chain dimers).

- Obstructive nephropathy.

- Analgesic abuse.

Tubular proteinuria, due to tubular or interstitial damage, may occur. Proteinuria results from failure of the tubules to reabsorb some of the plasma proteins that have been filtered by the normal glomerulus. The loss of protein is usually mild and may result from the following:

- Congenital disorders: Fanconi’s syndrome (a proximal tubular defect), cystinosis, renal tubular acidosis.

- Heavy metal poisoning: lead, cadmium, Wilson’s disease.

- Recovery phase of acute tubular necrosis.

- Chronic nephritis and pyelonephritis.

- Renal transplantation.

Overflow proteinuria may occur. This is when abnormal amounts of low molecular mass proteins (filtered at the glomerulus) are neither reabsorbed nor catabolized completely by the renal tubular cells (e.g., as in acute pancreatitis [amylase]). The following may be responsible:

- Multiple myeloma: Bence Jones protein.

- Hemolytic anemia and march hemoglobinuria: hemoglobin. March hemoglobinuria is due to repeated trauma and was first reported in soldiers after a long march.

- Myelomonocytic leukemia: lysozyme.

- Myoglobinuria and crush injuries: myoglobin.

History in the Patient with Hematuria and Proteinuria

- Ask about associated urinary symptoms, such as frequency (urinary tract infection, bladder calculus, prostatism), hesitancy, strangury (the desire to pass something that will not pass, e.g., a calculus), and dysuria (painful micturition reflecting urethral or bladder inflammation).

- Has the patient recently had an upper respiratory infection? A positive answer may suggest IgA nephropathy or post-streptococcal GN.

- Does the patient have a history of hypercalcemia, taking calcium, or parathyroid disorders?

- Is the hematuria worse with exercise? This suggests tumor or calculus.

- Ask about groin pain. This suggests pyelonephritis or renal calculi.

- Ask about colicky pain (especially flank pain). This suggests a ureteric calculus.

- Has there been a history of fever (e.g., with pyelonephritis)?

- Are there generalized features of carcinoma (e.g., anorexia and weight loss)?

- Ask about drugs, such as analgesics (nephropathy) or sulphonamides.

- Is there a history of trauma?

- Is there a past history of radiotherapy?

- Does the urine contain crystals or stones?

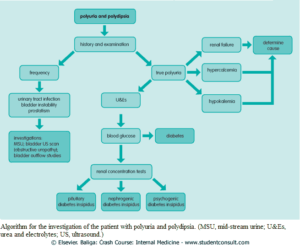

- Are there any signs of systemic or chronic illness, such as recurrent infections and polyuria with diabetes mellitus?

- Has there been recent foreign travel (e.g., schistosomiasis or tuberculosis)?

- Is there a positive family history? African Americans should be asked about a family history of sickle cell trait or disease.

- Are there clotting disorders-does the patient bruise easily?

- Is there a history of renal problems (e.g., polycystic kidney disease)?

- If hematuria is present in a woman, ensure that she is not menstruating.

- Ask about the appearance of the urine:

- If the urine is blood stained at the start of micturition and clear later on, the site of pathology is likely to be the urethra or prostate.

- If the urine is more blood stained toward the end of micturition, the site of pathology is likely to be the bladder.

- If the urine is evenly blood stained throughout micturition, the site of pathology is likely to be the kidney or ureter.

The following factors should be assessed, particularly if proteinuria is suspected:

- Ask about the appearance of the urine. Heavy proteinuria turns the urine dark and frothy. However, the urine may appear normal, and proteinuria may only be picked up on formal testing.

- Are there symptoms of urinary tract infection (e.g., frequency, dysuria, urgency, or incontinence)?

- Does the patient have a vaginal or penile discharge?

- Are there signs of systemic disease (e.g., diabetes mellitus)?

- Does the patient have a temperature or other signs of acute illness?

- Are there symptoms of congestive heart failure (e.g., shortness of breath, orthopnea, ankle swelling)?

- Ask about heavy metal exposure and other drugs (e.g., analgesic abuse).

- Is the proteinuria only present after vigorous exercise?

- Is the proteinuria absent in early morning specimens (orthostatic proteinuria)?

- Ensure that the patient is not pregnant.

- Do not forget to keep the causes of nephrotic syndrome in mind.

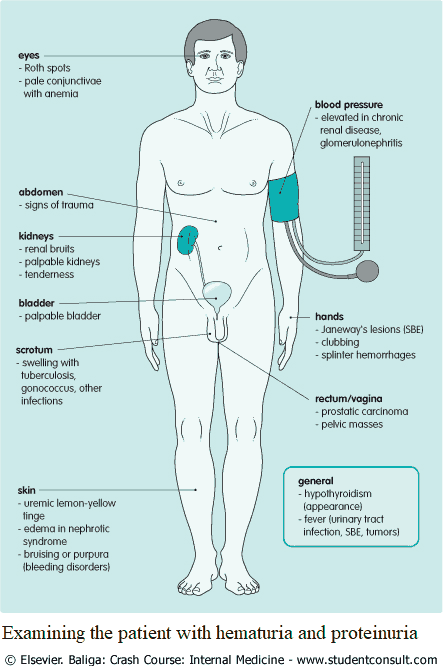

Examining the Patient with Hematuria and Proteinuria

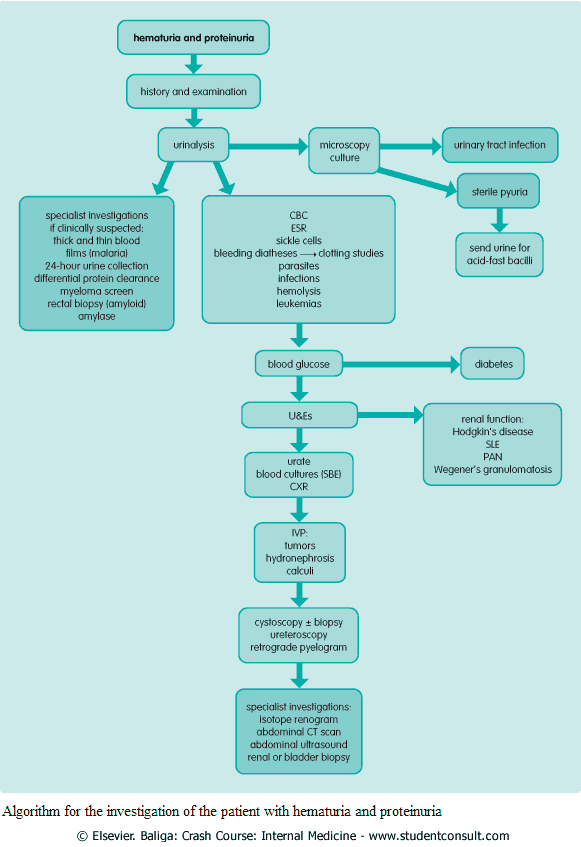

Investigating the Patient with Hematuria and Proteinuria

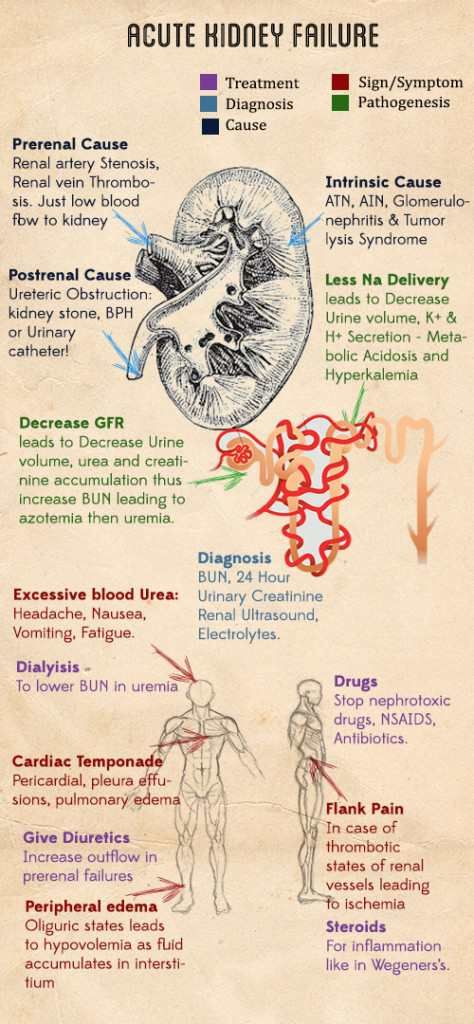

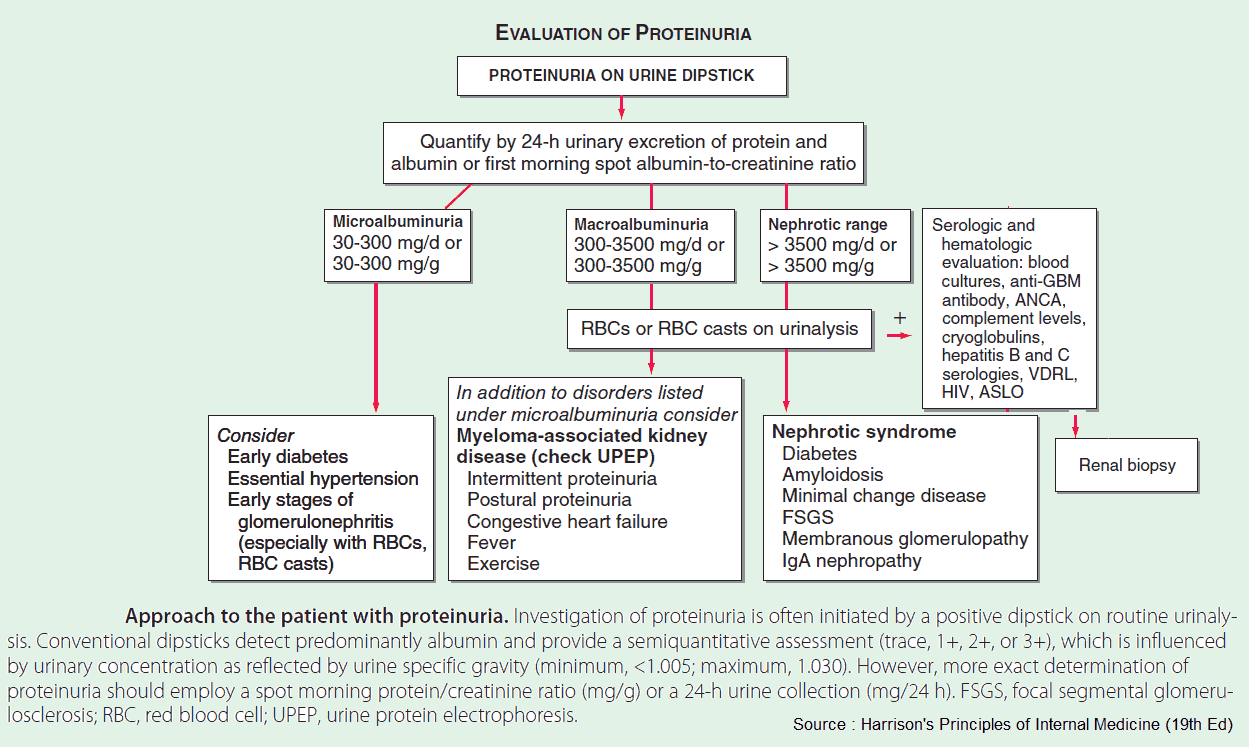

1. Urine Analysis

The following urinary tests should be performed:

- Albumin.

- Glucose.

- Urobilinogen: jaundice.

- Porphyrins: porphyria.

- Microscopy: red blood cells, white blood cells, casts, crystals, protein.

- Culture: infection.

- Causes of a sterile pyuria:

- Tuberculosis.

- Tumors.

- Analgesic nephropathy.

- Causes of a sterile pyuria:

- Early morning urine: acid-fast bacilli, if tuberculosis is suspected.

- Cytology: malignancy.

It is important to note that the urine dipstick detects predominantly albumin, not light chains and other smaller proteins. In addition, it takes >300-500 mg/day before the test becomes positive.

Urine may be tested for protein at different times in the day. Protein is normally absent in orthostatic proteinuria first thing in the morning before getting up. (The patient is asked to void the bladder before sleep). It may also be tested after exercise.

24-hour collection of urine for protein.

24-hour collection of urine for protein is useful for distinguishing mild to moderate proteinuria, in which the loss is not sufficient to cause protein depletion, from severe proteinuria, in which the loss is usually 5-10 g. More benign causes of proteinuria usually result in excretion of less than 1-2 g/day. In patients under the age of 30 years, the urine should be split into “upright” and “supine” specimens to aid in the diagnosis of orthostatic proteinuria.

Differential protein clearance

Differential protein clearance (selectivity) is occasionally performed in patients with nephrotic syndrome. Patients with selective proteinuria (small molecular mass proteins are cleared more rapidly than large proteins) are more likely to respond to steroid therapy.

Kidney biopsy

This is performed for patients who have 2-3 g/day of urine protein on a 24-hour collection. The renal biopsy can be helpful in nephritic syndrome to differentiate among causes and to direct treatment.

2. Blood Analysis

- Complete blood count: platelet deficiency in bleeding disorders, sickle cells, parasites, leukocytosis with infections.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

- Clotting studies: bleeding diathesis.

- Blood glucose: diabetes mellitus.

- Urea and electrolytes: renal function.

- Remember: urea and electrolytes may be normal despite significant renal disease.

- Urate: gout.

- Blood cultures: infective endocarditis.

- Specialized investigations according to clinical suspicion: thick and thin films for malaria; serum complement and autoantibodies for glomerulonephritis.

- Myeloma screen: immunoelectrophoresis; urine for Bence Jones protein.

- Hepatitis B, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus serology: potential causes of nephrotic syndrome.

3. Radiology

- Chest x-ray: primary and secondary tumors, tuberculosis, polyarteritis.

- Abdominal x-ray: renal outline and stones. Ninety per cent of renal calculi are opaque; urate, cysteine, and xanthine stones may be radiolucent.

- Intravenous pyelogram: excretory function, stones, shape of the calyces, ureters and bladder.

- Cystoscopy: bladder lesions.

- Ureteroscopy: ureter lesions.

- Retrograde pyelogram: stones or obstructive lesions in the ureters are suspected.

- Abdominal CT scan: to visualize the kidneys, adjacent organs, and other abdominal masses.

Read Also : Urolithiasis Guidelines