Table of Contents

Polyuria is the passing of excessive volumes of urine. Urine output depends on fluid intake and body losses, and typically ranges from 1-3.5 L/day.

Polydipsia, the ingestion of excessive volumes of fluid, is usually a consequence of polyuria.

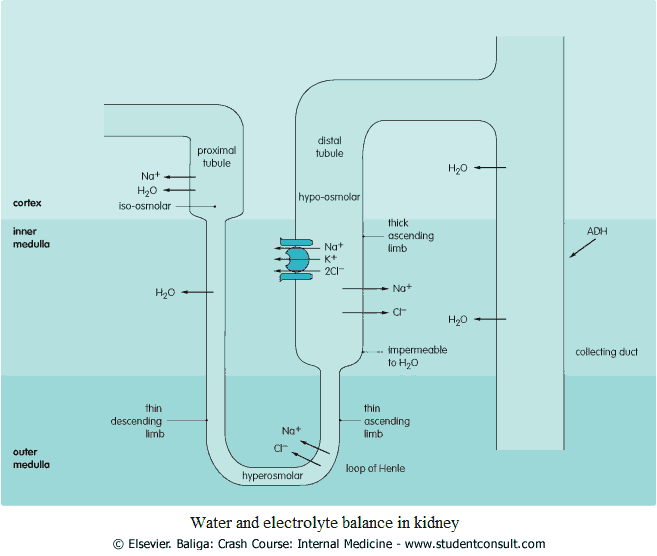

Water is normally reabsorbed from the loop of Henle as it passes through the hyperosmolar renal medulla. Fluid in the collecting ducts enters the hyperosmolar renal medulla, with water reabsorption being controlled by antidiuretic hormone (ADH) (image).

The secretion of this is controlled by the hypothalamus in response to osmolality changes in the blood. A rise in osmolality leads to an increase in ADH secretion, and a fall results in a decrease in ADH secretion.

The renin-aldosterone feedback cycle is also responsible for water retention. Cells in the juxtaglomerular complex are responsive to changes in the blood pressure coming into the afferent arteriole. When blood pressure is low, the cells secrete renin, which is cleaved to form angiotensin I, which in turn is cleaved in the lungs by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) to form angiotensin II.

Angiotensin II is a powerful vasoconstrictor and promotes the absorption of Na and water by acting on the tubules themselves and also through the stimulation of aldosterone secretion.

Differential Diagnosis of Polyuria

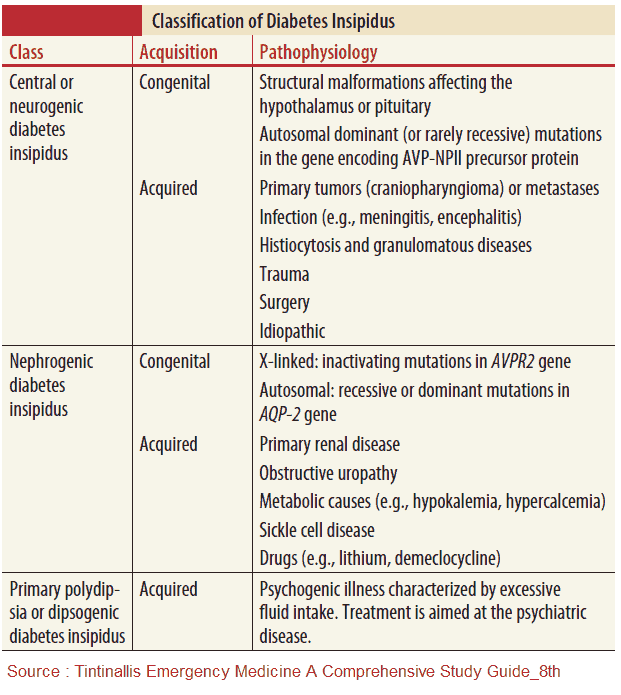

1. Insufficient Secretion of ADH (Central Diabetes Insipidus (DI))

Central diabetes insipidus (DI) may be secondary to lesions of the hypothalamic/pituitary axis and includes the following:

- Idiopathic: often familial and the most common form.

- Surgery or irradiation to the pituitary gland.

- Trauma: especially head injury.

- Malignancy (e.g., craniopharyngioma, pinealoma, glioma, and secondary deposits).

- Anorexia nervosa.

- Ischemia.

- Infections (e.g., meningitis and pneumonia).

- Infiltrations (e.g., sarcoid and histiocytosis X).

2. Inhibition of ADH release

This leads to increased thirst and thus polydipsia. Examples include psychogenic DI and lesions affecting the thirst center.

3. Inability of the kidney to respond to ADH (Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus (DI))

This is nephrogenic DI and may be congenital or acquired.

The familial form is due to a primary renal tubular defect.

The secondary defect may be due to an inability to maintain renal medullary hyperosmolality and includes:

- electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and hypokalemia,

- lithium toxicity

- longstanding pyelonephritis

- longstanding hypdronephrosis

- renal papillary necrosis (analgesic nephropathy)

4. Chronic Renal Failure

Chronic renal failure may occur as a result of the depressed ability of the kidneys to concentrate urine. The volume of urine may therefore increase to excrete the same osmotic load.

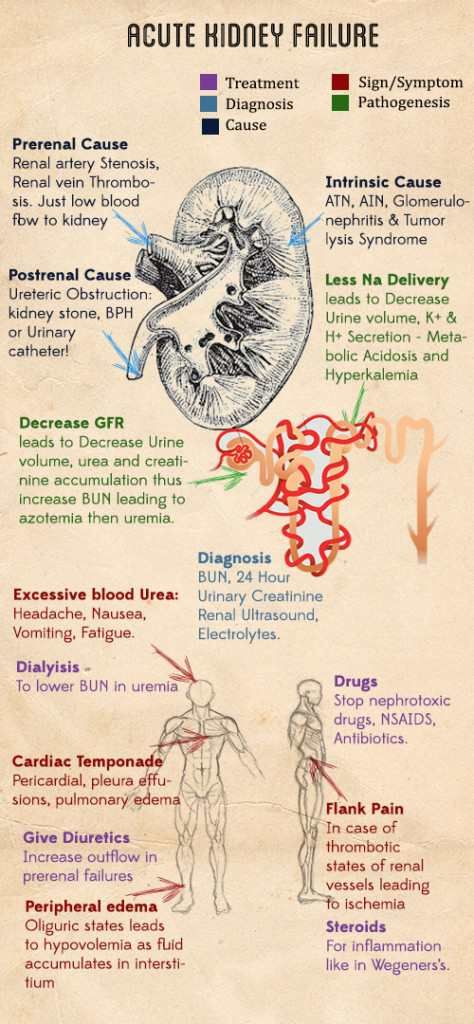

5. Acute Renal Failure

Polyuria occurs in the diuretic phase of acute renal failure and in postobstructive uropathy.

6. Osmotic Diuresis

Incomplete reabsorption in the tubules of substances in the glomerular filtrate leads to osmotic diuresis, i.e., increased solute per nephron. This occurs with:

- glucose in diabetes mellitus (DM)

- hypercalcemia in chronic renal failure

- intravenous infusion with hypertonic solutions (mannitol)

7. Other Causes

- Drugs (e.g., lithium carbonate, diuretics, amphoterecin B)

- Psychogenic polydipsia (e.g., schizophrenia)

- Excessive hypertonic fluid intake

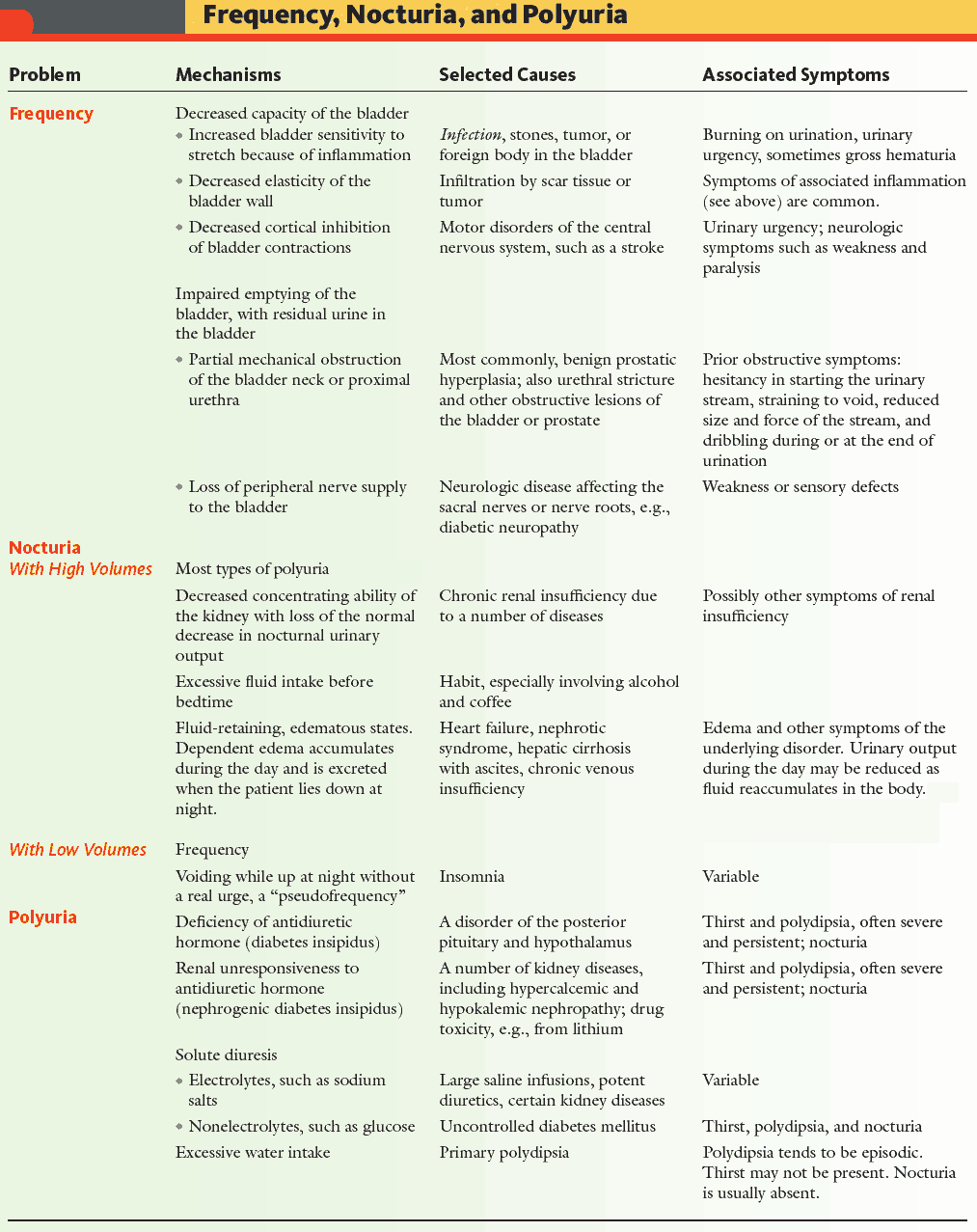

History in the Patient with Polyuria or Polydipsia

After asking general questions, focus on suspected causes. The following should be ascertained:

- Differentiate between polyuria (an increase in urine production) and frequency (the frequent passage of small amounts of urine).

- Weight loss: think of diabetes; malignancies (especially of the brain-does the patient have headaches?); myeloma leading to renal failure; ectopic production of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH); and bony metastases. Look for signs of anorexia nervosa (<15% of ideal body weight).

- General features of infection: a history of recurrent infection should suggest diabetes.

- Psychiatric symptoms: especially if thirst appears to dominate the picture, patients may resent investigations, especially a water deprivation test, and may drink surreptitiously. There may be an inconsistency or variation in the severity of the symptoms, and an absence of nocturnal symptoms. There may also be other neurotic symptoms.

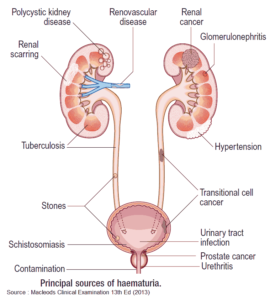

- Symptoms of renal failure: such as hematuria, nausea and vomiting; likely precipitating factors.

- If renal failure is suspected, consider associated systemic conditions, such as collagenoses (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus and polyarteritis nodosa), gout, subacute bacterial endocarditis, amyloid, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and Goodpasture’s syndrome.

- Hypercalcemia: produces symptoms of nausea, vomiting, constipation, abdominal pain, and, if severe, confusion and coma.

- Hypokalemia: leads to muscle weakness and paralysis.

- Drug history: analgesic abuse may cause renal papillary necrosis; lithium may cause nephrogenic DI; vitamin D or milk-alkali syndrome may lead to hypercalcemia; steroids and nephrotoxic drugs.

- History of head injury or childhood meningitis?

- History of hypertension? If so, suspect hypertensive renal disease.

- Family history (e.g., in DI, DM, and nephrogenic DI).

Examining the Patient with Polyuria or Polydipsia

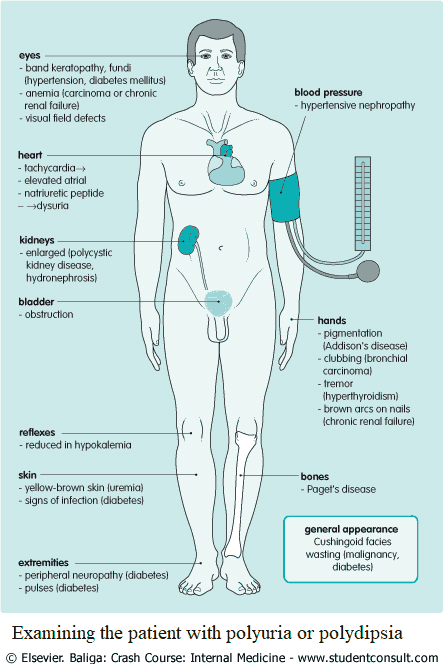

The general appearance of the patient should be noted:

- Yellow-brown skin: renal failure, liver failure.

- Skin manifestations: DM (e.g., necrobiosis lipidica diabeticorum, granuloma annulare, infections).

- Wasting: malignancy or diabetes.

- Anemia: malignancy or chronic renal failure.

- Clubbing: bronchogenic carcinoma leading to excess ACTH or parathyroid hormone (PTH) production.

- Brown arcs on nails: chronic renal failure.

- Optic signs: band keratopathy or subconjunctival calcification in hypercalcemia; visual defects in tumors of the hypothalamus or pituitary; fundal changes of hypertension or diabetes.

Cardiovascular system

Check for tachycardias (producing atrial natriuretic peptide) and peripheral vascular disease in DM. Also, check the blood pressure for hypertensive nephropathy.

Abdominal examination

Palpate the kidneys as they may be palpable in polycystic kidney disease or hydronephrosis. A large bladder may indicate urinary tract obstruction.

Neurologic examination

The neurologic examination should assess the following:

- Other signs of drug toxicity (e.g., diplopia, dizziness, nausea)

- Diabetic peripheral neuropathy.

- Hypotonia and areflexia with hypokalemia.

- Wasting in malignancy.

- Paraneoplastic syndromes.

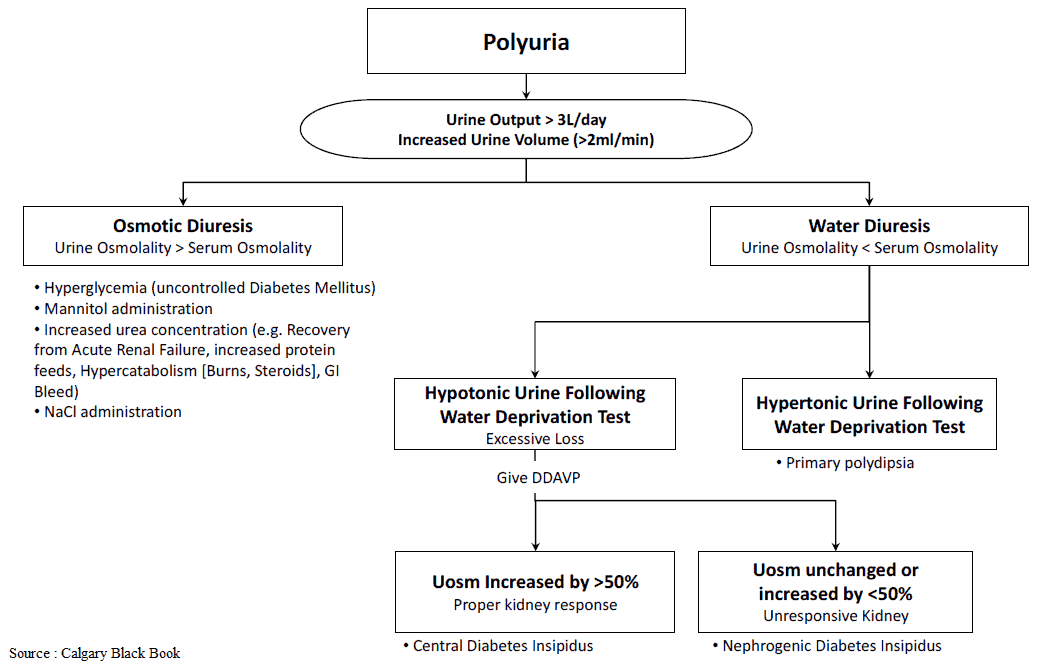

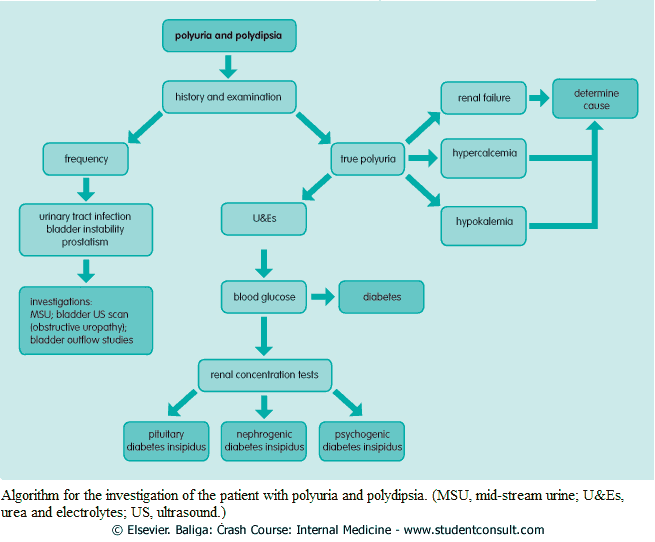

Investigating the Patient with Polyuria and Polydipsia

- Collect 24-hour urine and confirm polyuria if any doubt exists.

- Urinalysis: specific gravity with or without osmolality.

- Urea and electrolytes: renal failure and hypokalemia. If renal impairment is found, further investigations may include creatinine clearance, tests for systemic diseases associated with renal failure, and an ultrasound scan of the kidneys. (If hypokalemia is found, go through the differential diagnosis. Remember simple things like drugs-is the patient on diuretics?).

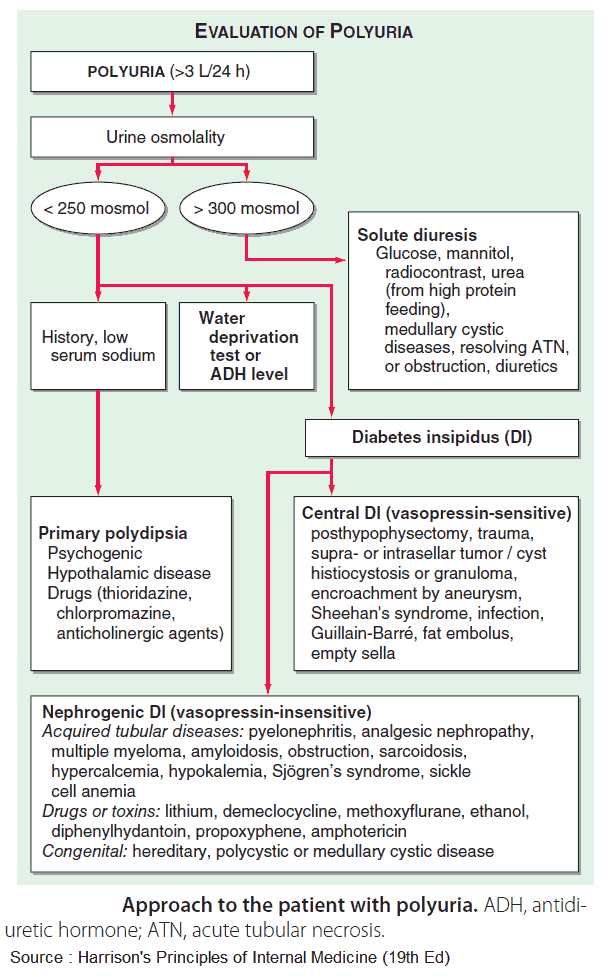

- Dehydration test – does the patient appropriately concentrate urine?

- Blood glucose: DM.

- Administer vasopressin. If the patient responds to exogenous ADH, central diabetes insipidus is confirmed. If the patient is still unable to respond, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is confirmed.

- Complete blood count: anemia with chronic renal failure, or malignancy (e.g., leukemia), and reticuloses.

- Serum calcium corrected for plasma proteins: if raised, further tests to elucidate the cause will be required, such as PTH assay, tests of pituitary function, bone scan, myeloma screen, alkaline phosphatase, and bone x-rays for Paget’s disease, thyroid function tests, and serum angiotensin-converting enzyme for sarcoidosis, and synacthen test to exclude adrenal insufficiency.

- Chest x-ray (CXR): bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy with sarcoidosis, and bronchial neoplasm with ectopic PTH secretion. If there are any abnormalities on the CXR it may be necessary to proceed to bronchoscopy with or without biopsy.

- Skull x-ray: brain tumor (e.g., craniopharyngioma or secondary deposits).

If either a hypothalamic or pituitary cause or renal tubular dysfunction is suspected, it may be appropriate to proceed with renal concentration tests. It is mandatory to exclude other potential causes for polyuria, as renal concentration tests may be dangerous.

The patient is told to drink nothing from 4 pm the day before attending the outpatient department. If the urine osmolality the next morning is not above 800 mmol/kg, inpatient tests are required.