Table of Contents

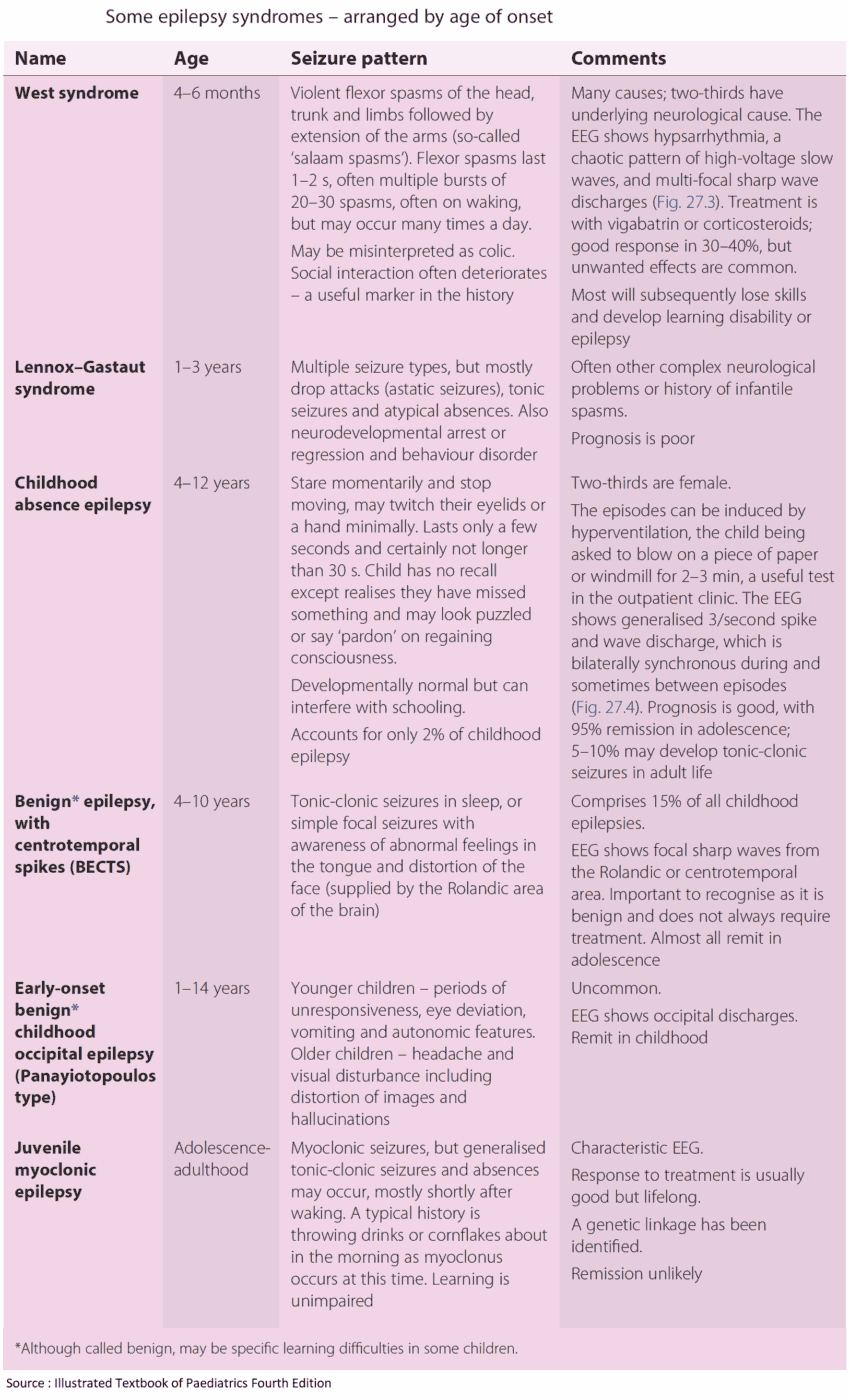

Epilepsy refers to a group of conditions in which paroxysms of abnormal electrical activity of cerebral neurones results in seizures. As many as 1 in 20 of the general population have a fit at some time in their lives, and between 0.5% and 1.0% of the U.S. population has epilepsy.

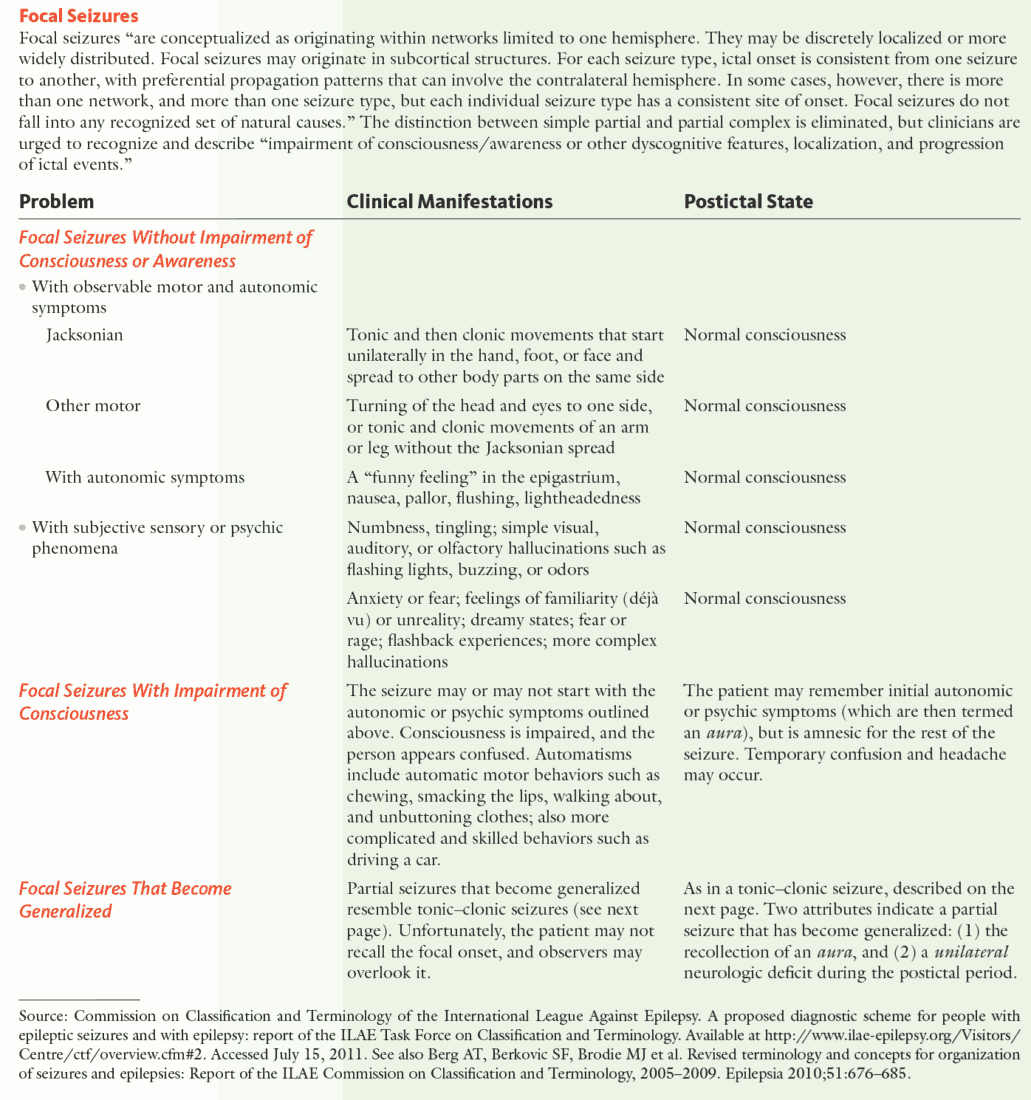

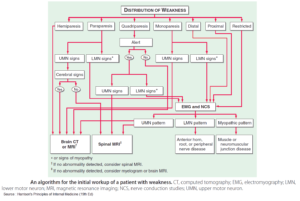

Classification of Epilepsy and Seizures

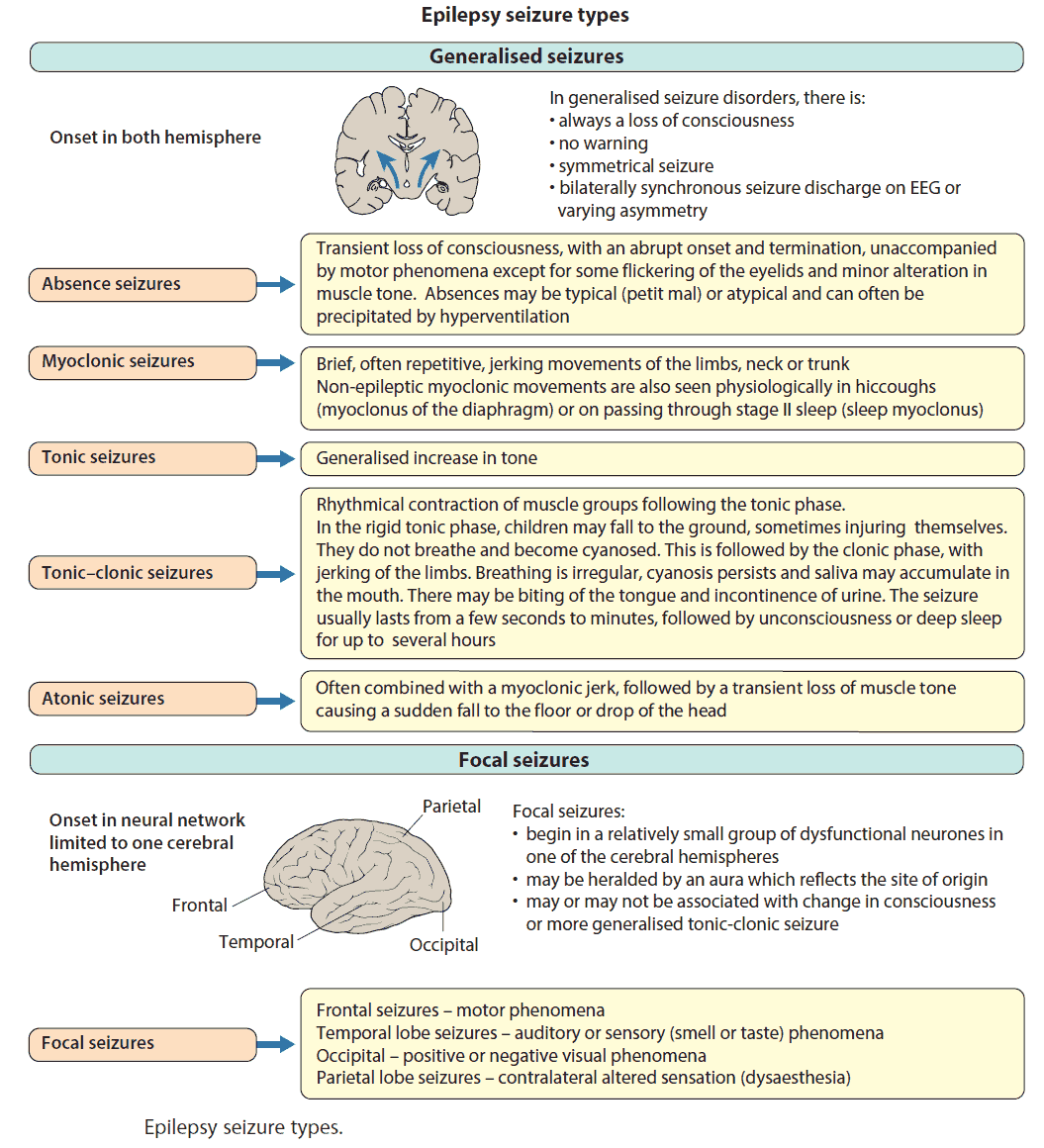

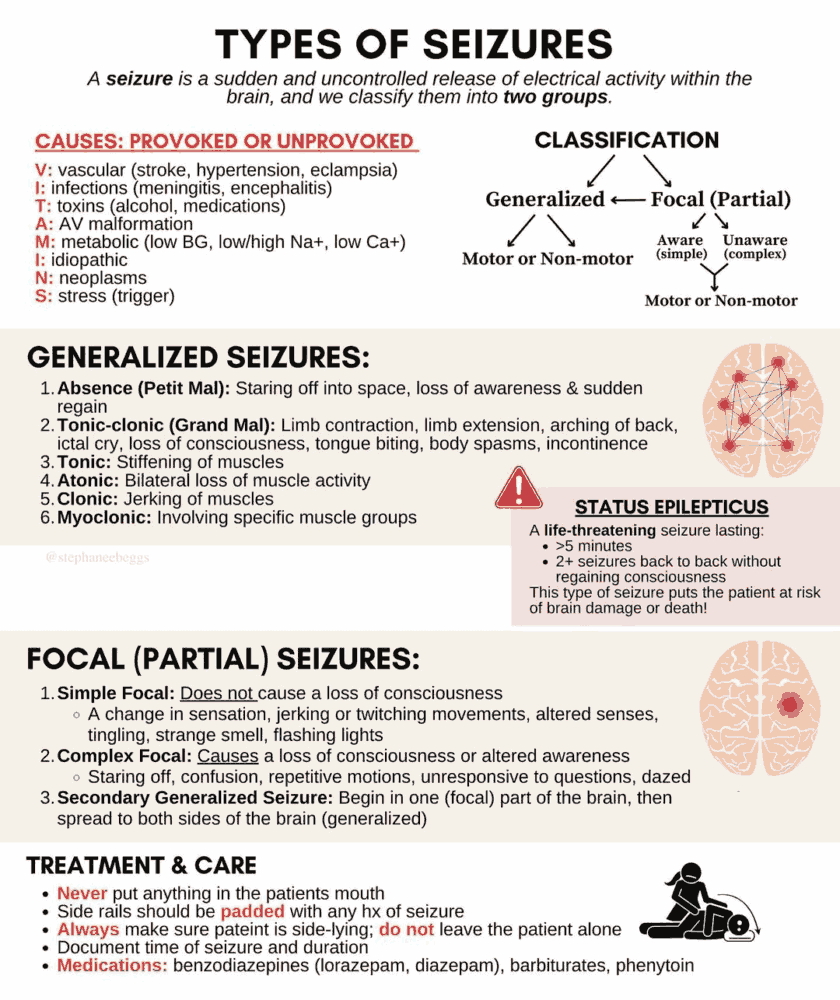

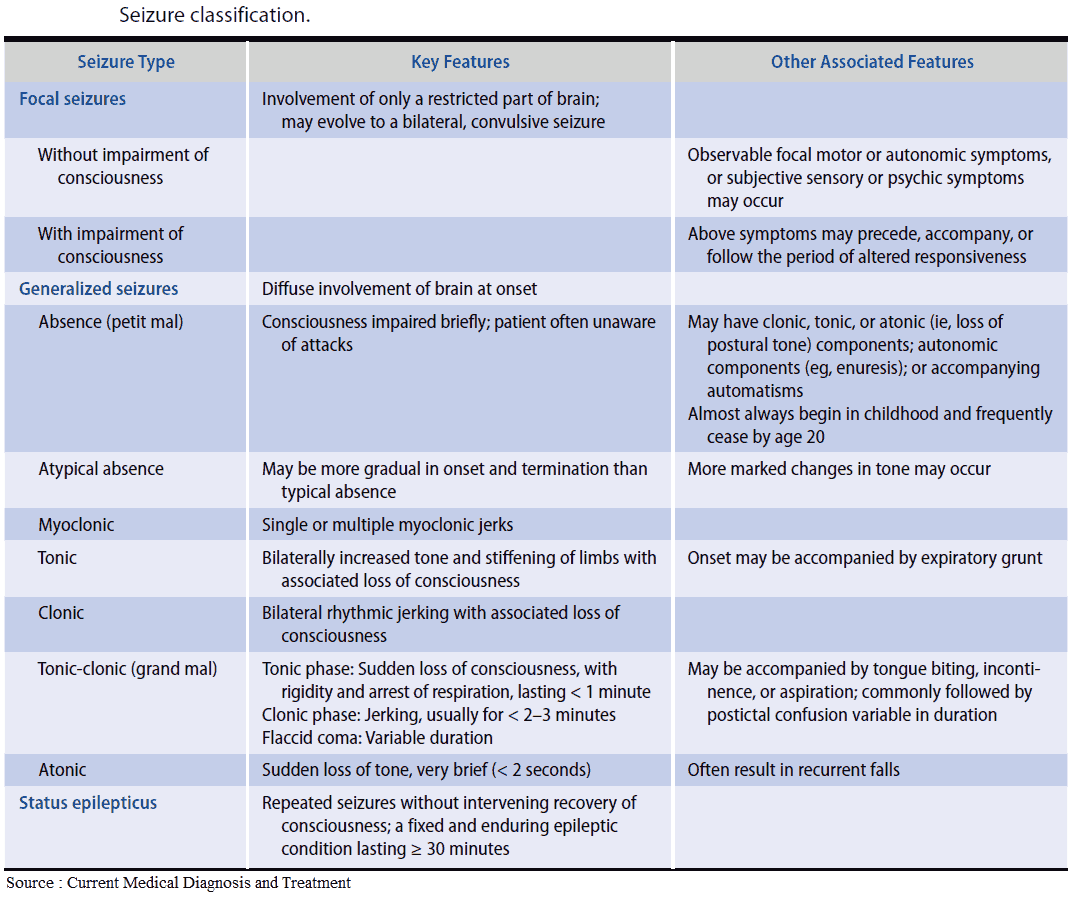

Seizure disorders can be divided into two main groups:

- Idiopathic generalized onset seizures

- Focal onset (localization-related, partial) seizures

1. Idiopathic generalized onset seizures

These are mostly genetic in origin and are often associated with a characteristic spike and wave on electroencephalogram (EEG).

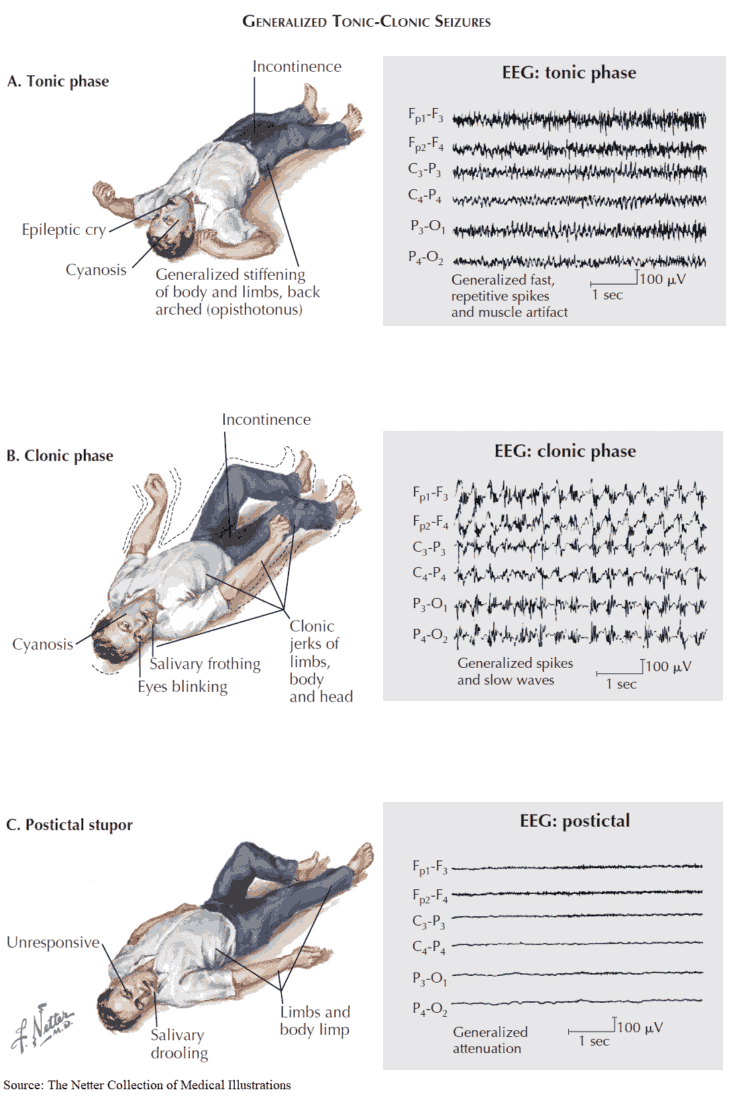

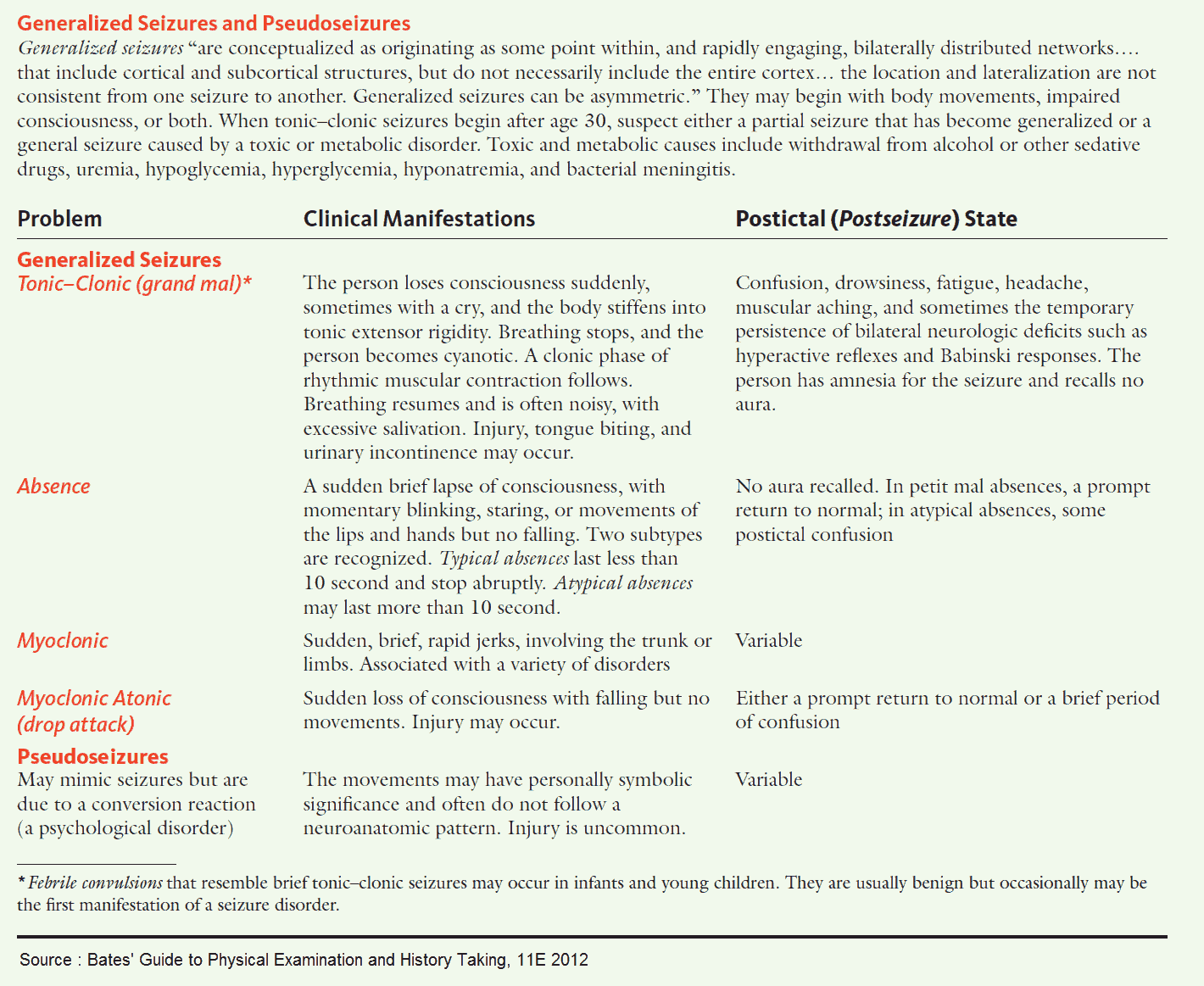

Tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizures

Before the seizure the patient may be irritable and experience minor disturbances such as myoclonic jerks. There may be a strange feeling (aura) before the seizure, which has a sudden onset. The tonic phase involves powerful muscular contractions. The patient is struck unconscious and falls rigidly to the ground. Teeth are clenched; cyanosis may occur.

After about a minute, the clonic phase starts, consisting of violent convulsive movements. There may be tongue biting and urinary or fecal incontinence. The patient then becomes drowsy or will sleep for several hours. The reflexes are depressed, with a positive Babinski sign. The patient may be confused on waking (postictal confusion).

Absence attacks (petit mal)

These start in childhood and are accompanied by a characteristic EEG pattern of three spike-and-wave discharges per second. It is due to a congenital neuronal instability. There are brief interruptions of consciousness, sometimes accompanied by rhythmical blinking of the eyelids.

To an observer, the child may appear to be dazed or daydreaming. Recovery is immediate, and there are no sequelae. Children can have hundreds of these episodes per day. In evaluating a child with suspected petit mal seizures, ask about such indicators as school performance; these seizures can be detrimental to school work.

Myoclonic seizures and epilepsy

This is a form of idiopathic epilepsy developing in early childhood. Various types of generalized seizures occur, including sudden jerking movements of the limbs (myoclonus).

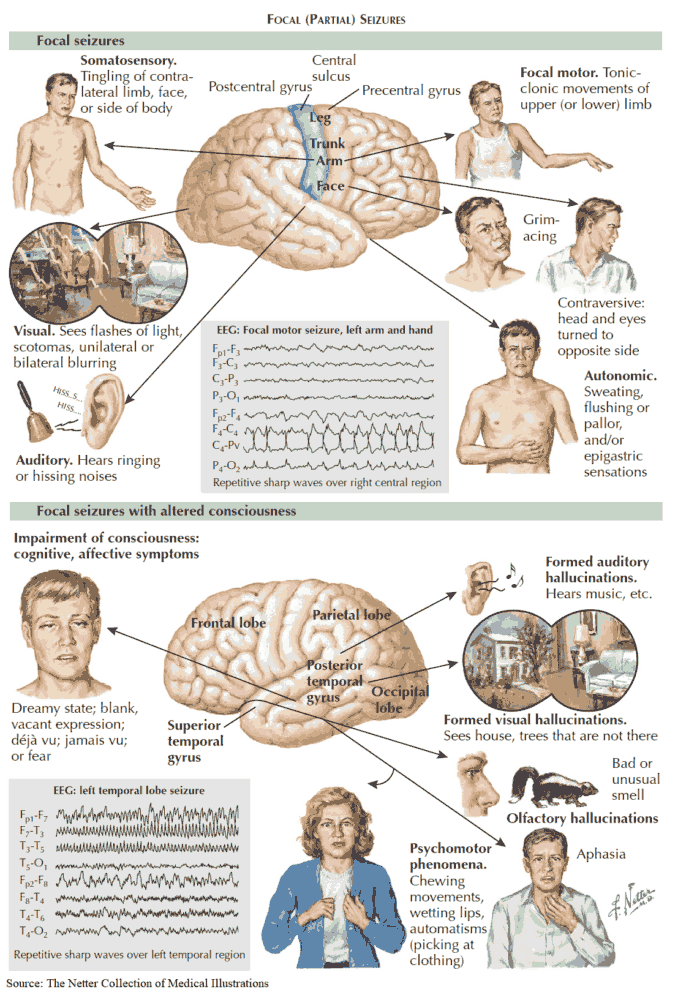

2. Focal onset (localization-related, partial) seizures

These have a focus of activity (e.g., a tumor or scar tissue caused by trauma or stroke), from which epileptic activity begins and then spreads. They may lead to generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The nature of the attack varies according to the primary site of the lesion. Examples include focal motor attacks, focal sensory attacks, and temporal lobe epilepsy.

Focal motor attacks

These arise in the precentral motor cortex and consist of clonic movements in localized groups of muscles such as the hand or face. They may continue for hours, in which case it is called epilepsia partialis continuans.

The discharge may spread along the precentral gyrus causing a march of clonic movements throughout the body (Jacksonian seizure). After the seizure there may be a short-lived weakness of the affected parts of the body (Todd’s paresis).

Focal sensory attacks

These start in the postcentral sensory cortex, and either localized or spreading paresthesias occur.

Temporal lobe epilepsy

This may consist of hallucinations of any of the five senses and of memory. Gustatory and olfactory hallucinations are usually unpleasant. Jamais vu is a sudden feeling of unfamiliarity while the patient is in his or her own environment and déjà vu is a vivid sense of familiarity with the current situation.

In automatism, the patient remains conscious but “dreamy” and may continue with normal activities. The patient cannot remember these events after the attack.

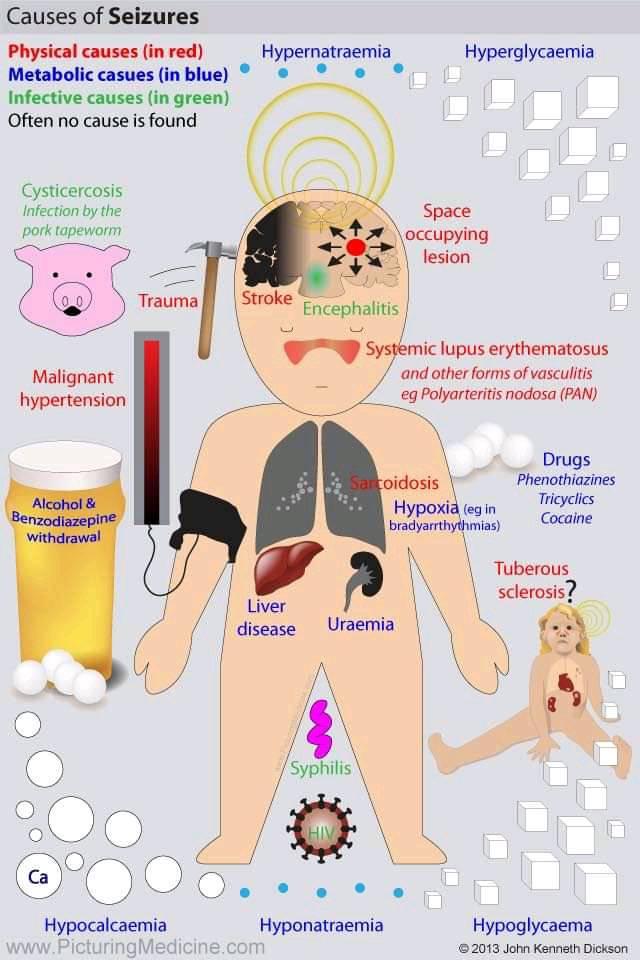

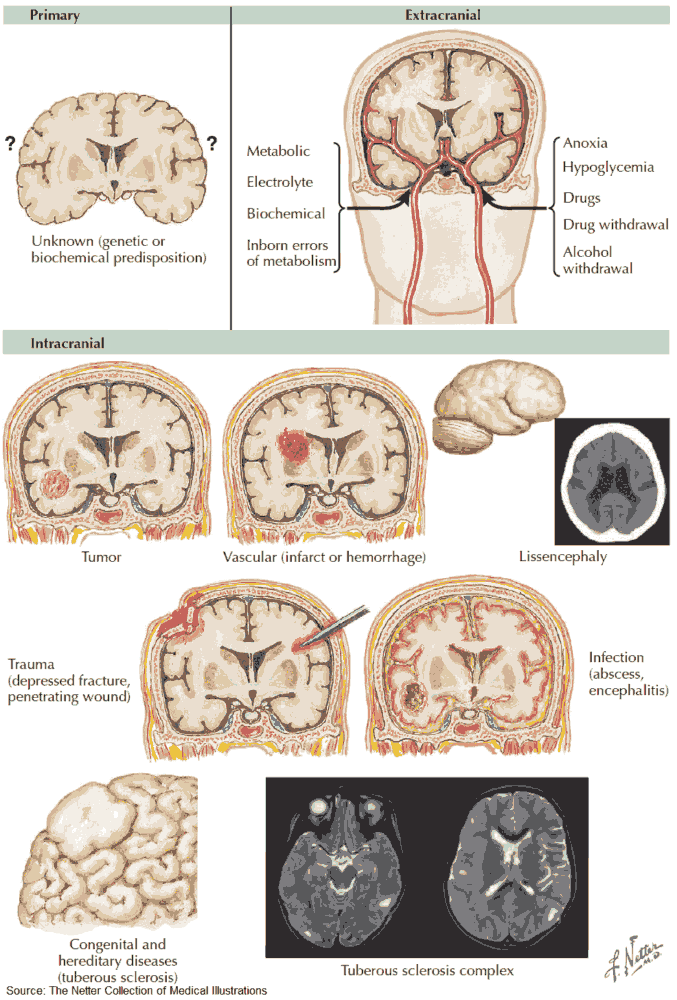

Etiology of Epilepsy and Seizures

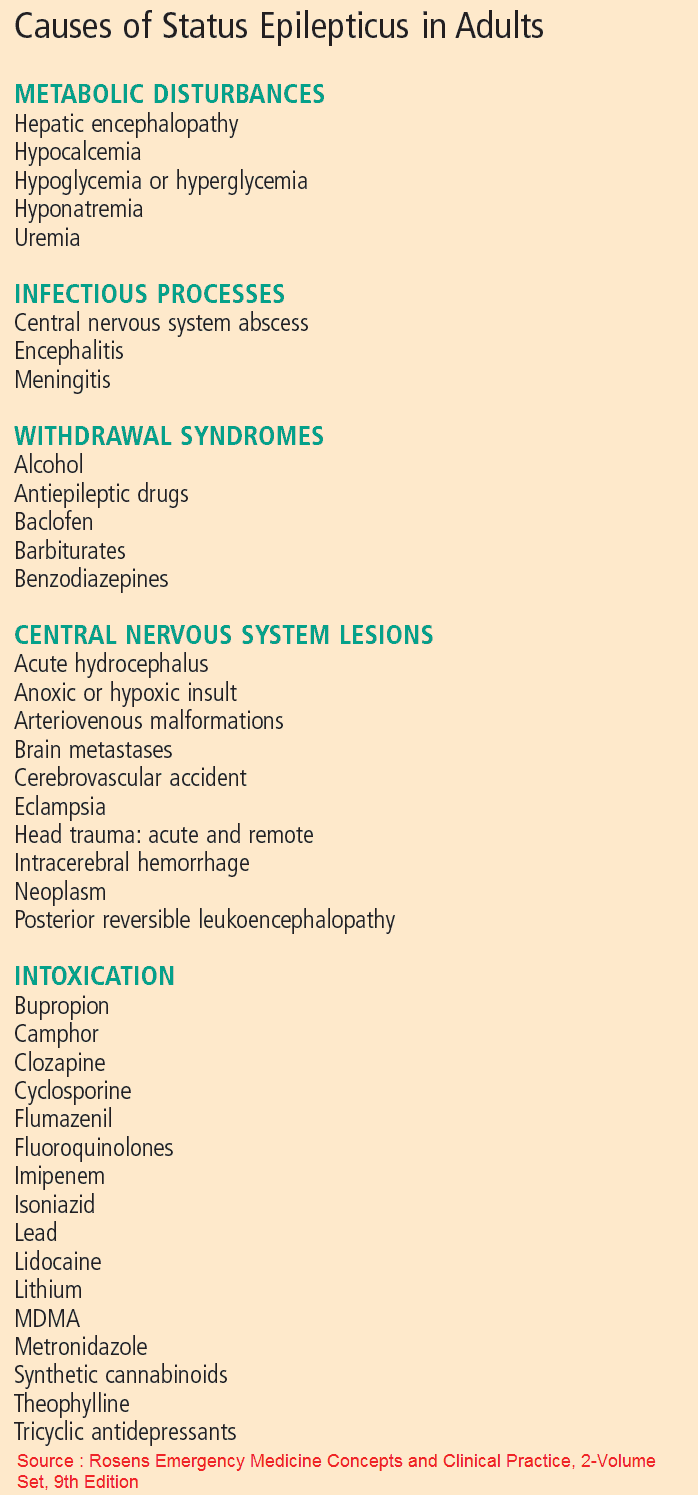

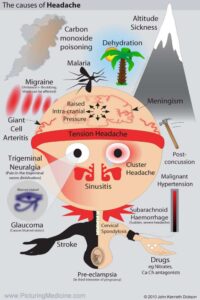

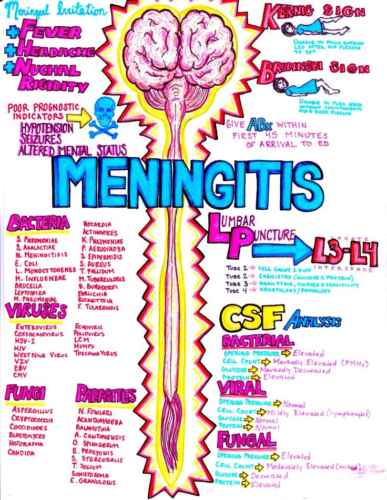

Although most seizures are idiopathic, a cause for the epilepsy and precipitating factors should be looked into. These include the following:

- Metabolic causes: hypoxia, hyper- or hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, uremia, alcoholism, hypo- and hypernatremia, liver failure, pyridoxine deficiency.

- Drugs and toxins: alcohol, lead, and drugs (e.g., phenothiazines, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, amphetamines, lidocaine, nalidixic acid [a quinolone antibiotic]).

- Trauma and surgery (e.g., perinatal trauma or head injury).

- Space-occupying lesions.

- Cerebral infarction.

- Other organic brain diseases: SLE, PAN, sarcoidosis, vascular malformations.

- Infections: encephalitis, syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus.

- Degenerative brain disorders: Alzheimer’s disease, Creutzfeld-Jacob disease.

Precipitants of epilepsy and seizures

Seizures may be precipitated by:

- flashing lights

- fever

- irregular meals

- menstruation

- hyperventilation leading to alkalosis

- lack of sleep

- emotional disturbances

- pregnancy

Differential Diagnosis

In taking a history it is important to keep in mind a differential diagnosis of conditions causing transient loss of consciousness. These include the following:

- Syncope: this is due to cerebral ischemia. The onset is gradual, and the patient slips to the floor. Recovery occurs after 1-2 minutes and is gradual. The patient is back to normal within a few minutes.

- Drop attacks: these involve a sudden weakness of the legs, making the patient fall. They are most commonly due to vertebrobasilar artery insufficiency.

- Hypoglycemia: the onset is prolonged, and the patient is confused, sweating, and light-headed. A time relationship to meals may be established.

- Narcolepsy: irresistible diurnal attacks of sleepiness. The patient may experience visual or auditory hallucinations when falling asleep (hypnogogic hallucinations). The patient wakes within a few minutes, feeling well.

- Cataplexy: a sudden loss of muscle tone so that the patient crumples to the ground.

- Micturition, defecation, and cough syncope: fainting after the respective acts.

- Carotid sinus syncope: this is due to supersensitivity of the carotid sinus to external pressure.

- Postural hypotension: either autonomic or secondary to drugs.

- TIAs, especially in the posterior cerebral circulation.

- Cardiac arrhythmias: due to impaired cardiac output; the loss of consciousness is sudden and the patient goes pale; there may be flushing on regaining consciousness.

- Psychogenic (hysterical seizures): there is usually some apparent gain for the patient, although he or she is seldom aware of the motivation. The seizures usually only occur in front of an audience. There is often active opposition on attempting to examine the patient. There may be strange cries and flailing limbs in an attempt to mimic true epilepsy.

Investigations in Epilepsy and Seizures

After a careful history and examination to consider differential diagnoses, blood tests include CBC, metabolic panel, serum calcium, liver function tests, and glucose. A CXR and ECG should be performed.

The diagnosis should not be based solely on the EEG because 10-15% of the general population may have an “abnormal” EEG, and approximately 15% of people with epilepsy never have specific epileptiform discharges.

CT scanning as the sole basis of diagnosis is also unreliable. The frequency of abnormalities found in CT scans in people with epilepsy varies greatly. A CT scan is indicated in a patient with late-onset epilepsy who has focal seizures, because it may detect a tumor.

Treatment of Epilepsy

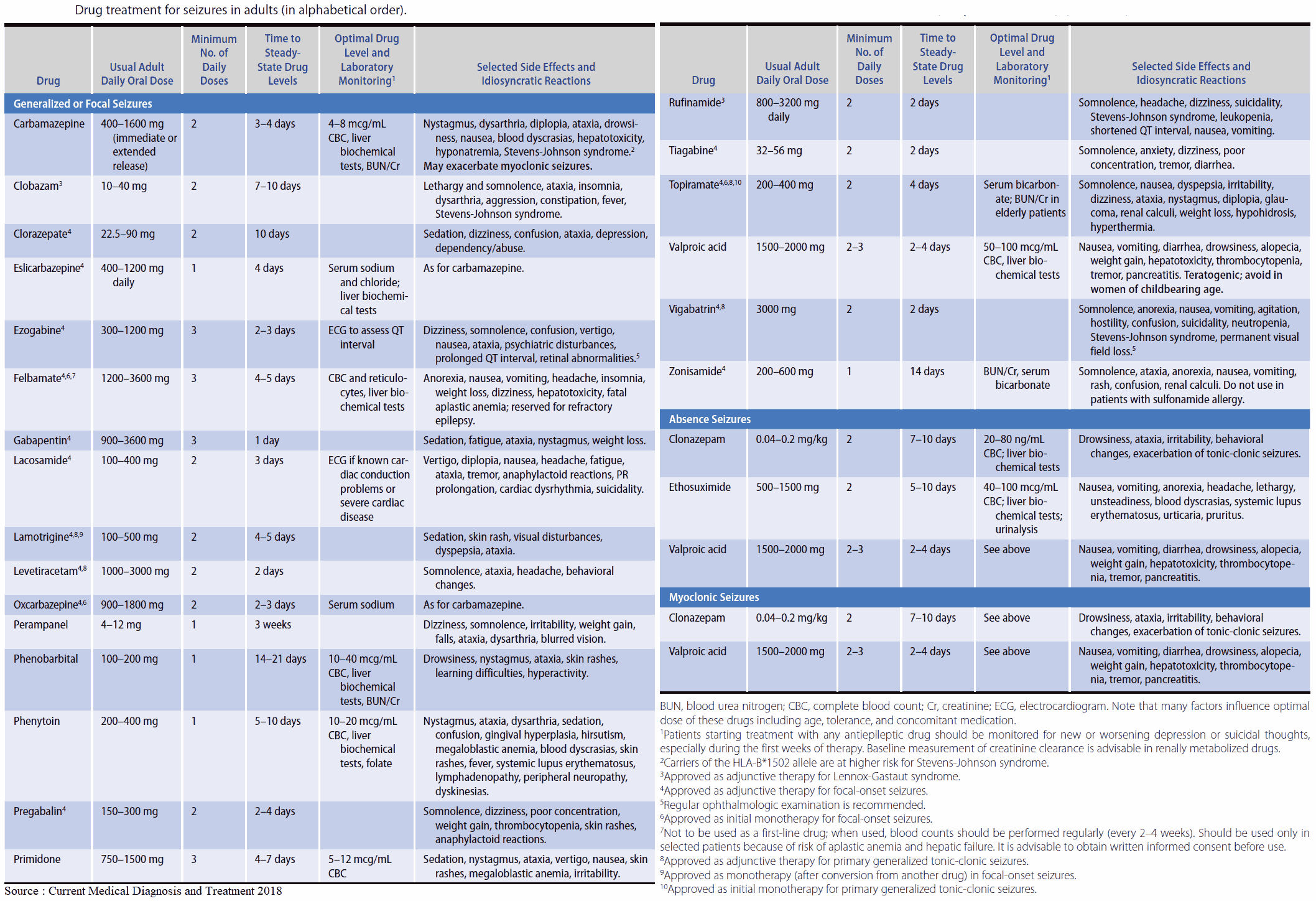

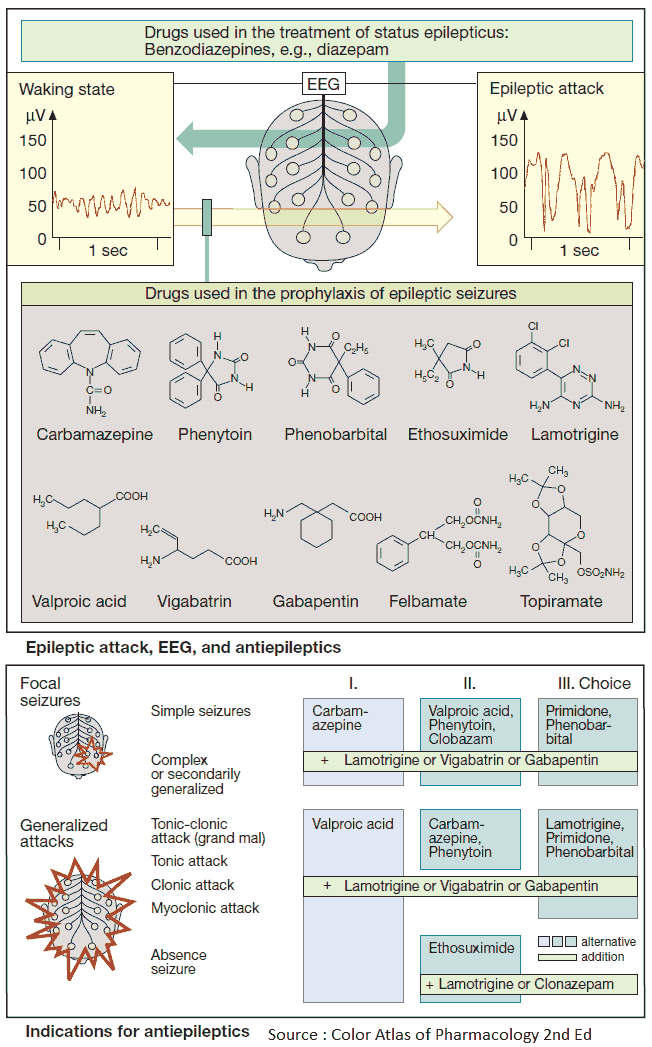

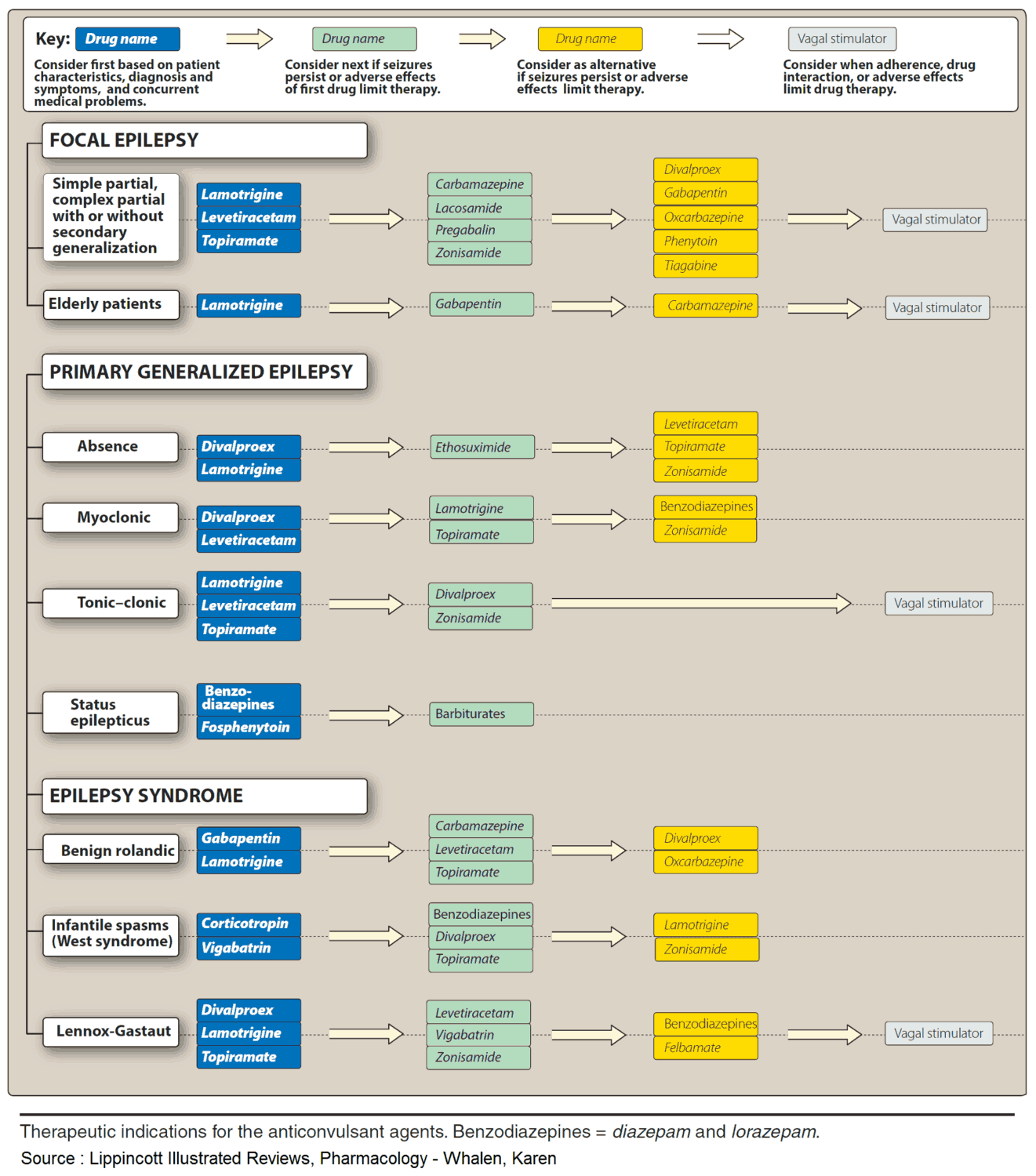

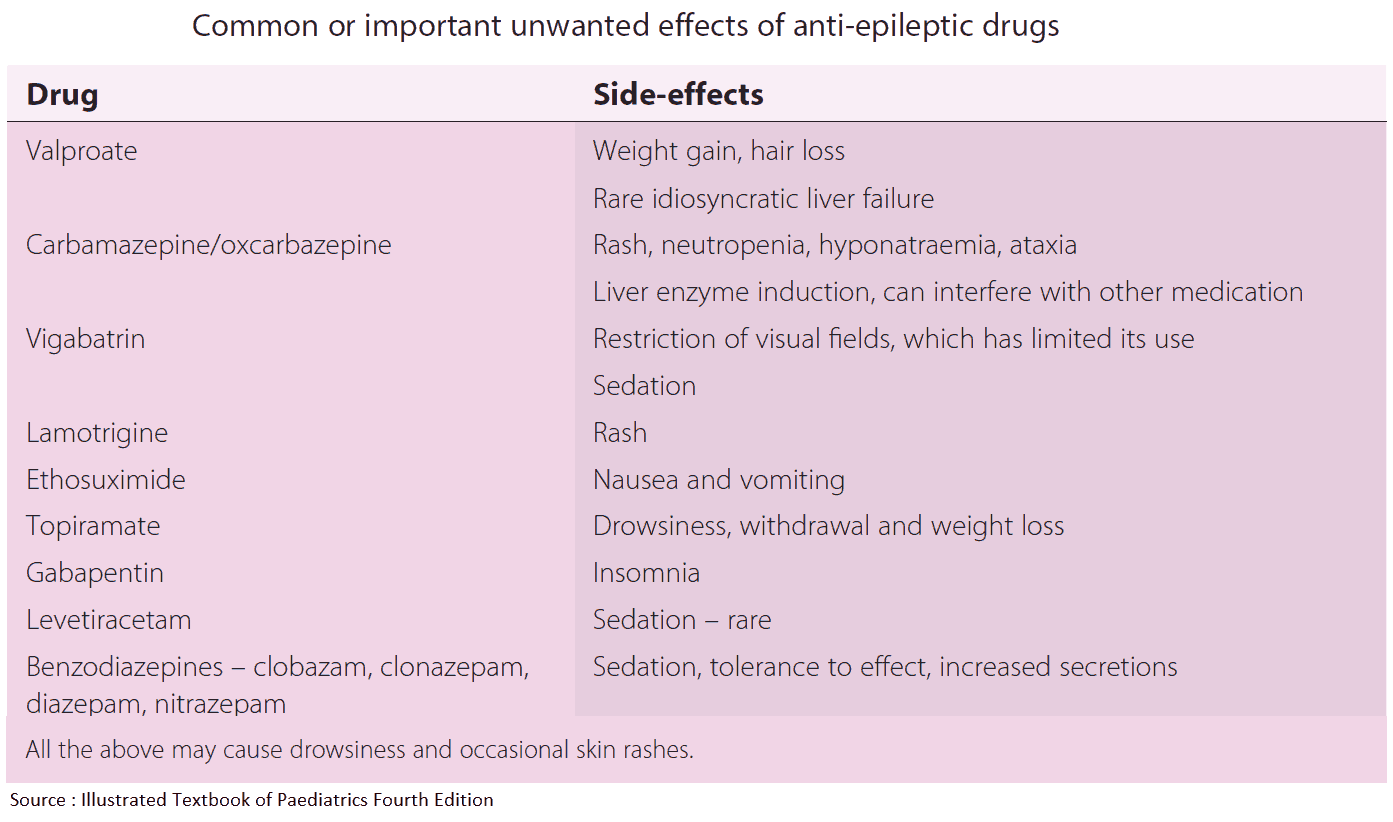

The aims of drug treatment are to prevent seizures while keeping the patient free of side effects. Antiepileptic drugs should be prescribed singly, using the lowest dose to obtain complete seizure control with minimum side effects. A single drug will suffice in approximately 80% of patients; the remainder need a second drug to achieve acceptable control. Localization-related epilepsy is more likely to be refractory.

Carbamazepine, phenytoin, and barbiturates all induce hepatic enzymes and therefore speed up the metabolism of estrogens and progestogens, making the oral contraceptive pill unreliable. Valproate does not affect oral contraceptive efficacy.

Treatment should be based on the type of seizure. For instance, certain medications are more effective in treating partial seizures than others (see below). Patients who have had an isolated seizure related to a metabolic or infectious cause can usually be spared treatment with anticonvulsant medications.

Risk factors for recurrent seizures include:

- A mass lesion shown on CT or MRI (e.g., stroke, neoplasm).

- A focal neurologic deficit.

- Past brain injury or cognitive impairment.

- Abnormal EEG.

Epileptics should be encouraged not to drink alcohol, since more than 3 drinks can increase the risk of seizure. By law in many states, physicians are required to report seizures, and driving limitations may be imposed. Epilepsy can have profound social consequences, including discrimination and exclusion from certain jobs (e.g., the armed forces). Personal implications include feelings of insecurity.

Patients who have had a seizure-free period of 2 years should be given a trial period off the medication. About 60% will have to return to taking medication. Patients who have refractory disease, especially those with a specific brain lesion, should be considered for surgery. Although studies are lacking, reported cases in the hands of a specialty center are generally encouraging.

First-line drugs

Idiopathic generalized oneset epilepsy

Phenytoin is often recommended as the treatment of choice because carbamazepine is ineffective for the treatment of absence or myoclonic seizures. Phenytoin, valproate, and carabmazepine are equally as effective for idiopathic generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Common unwanted effects of valproate include weight gain, hair thinning, and tremor. Hepatotoxicity, thrombocytopenia, and pancreatitis may occur. Note that loading a patient with phenytoin after a seizure (usually 20 mg/kg) can lead to hypotension. Use of fosphenytoin can prevent this side effect. Ethosuximide and valproate are useful alternatives in children with absence seizures only.

Focal onset (localization-related, partial) epilepsies

Carbamazepine, sodium valproate, phenytoin, and phenobarbitol are equally effective. However, they differ in their side-effect profiles and ease of use, and because of this carbamazepine and valproate have become the drugs of first choice.

Carbamazepine may cause CNS side effects (e.g., dizziness, nausea, headaches, and drowsiness), which may be avoided by slowly increasing the dose. It induces hepatic microsomal enzymes and so increases the metabolism of phenobarbitol, valproate, lamotrigine, corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, theophylline, and warfarin. It also inhibits the metabolism of phenytoin. Idiosyncratic reactions include the Stevens-Johnson syndrome, exfoliative dermatitis, and hepatitis.

Second-line drugs

Phenytoin is useful but often difficult to use because of its unpredictable pharmacokinetics, and so the best dose is difficult to determine. Phenobarbitol affects cognition and behavior and is no longer considered a first-line drug. Primidone is partly metabolized in the liver to phenobarbitone and is no longer recommended.

Add-on drugs

Vigabatrin, lamotrigine, and gabapentin are used as add-on therapies for partial or secondarily generalized seizures. They are equally effective.

Vigabatrin may cause drowsiness, fatigue, irritability, weight gain, and psychosis.

Lamotrigine can precipitate carbamazepine toxicity, so if unwanted effects such as diplopia occur, the dose of carbamazepine should be reduced. It causes a mild maculopapular rash in 5% of patients, the incidence of which can be reduced by starting at a low dose.

Gabapentin is renally excreted so the dose should be reduced in patients with renal impairment. The most common side effects are somnolescence, dizziness, and ataxia.

The benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam, may also be used. Clobazem can be used as an add-on for people with refractory epilepsy. Taken continuously it can cause dependence. Clonazepam is useful in children with myoclonic or tonic-clonic seizures. Sedation and tachyphylaxis are common, and withdrawal seizures may occur. It should be used only rarely.

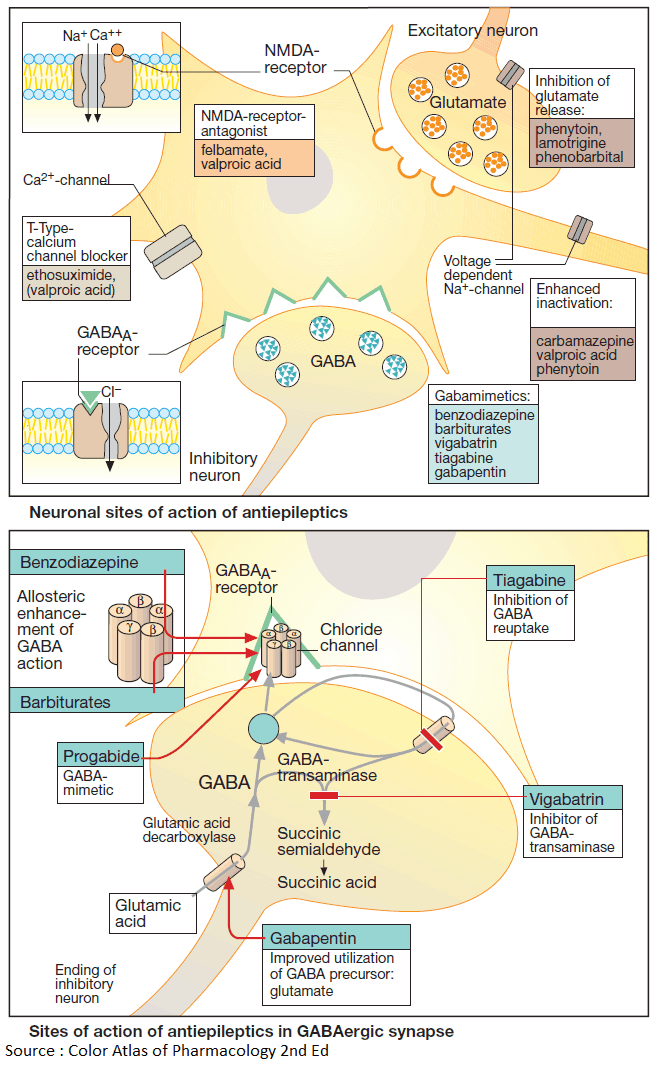

READ MORE about Antiepileptics – Summary

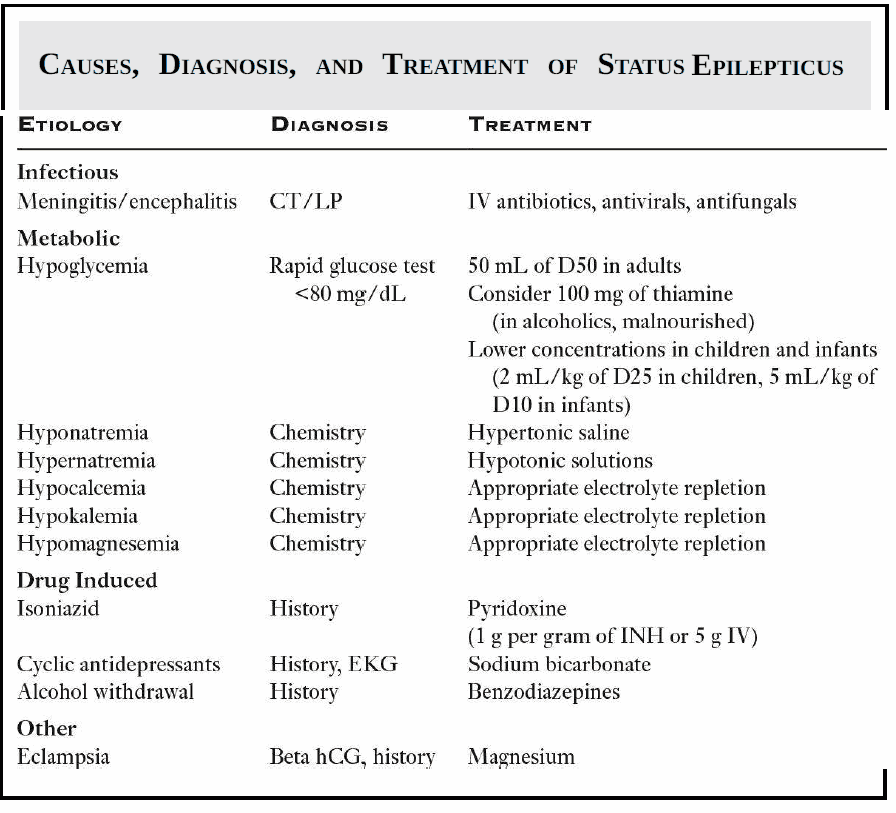

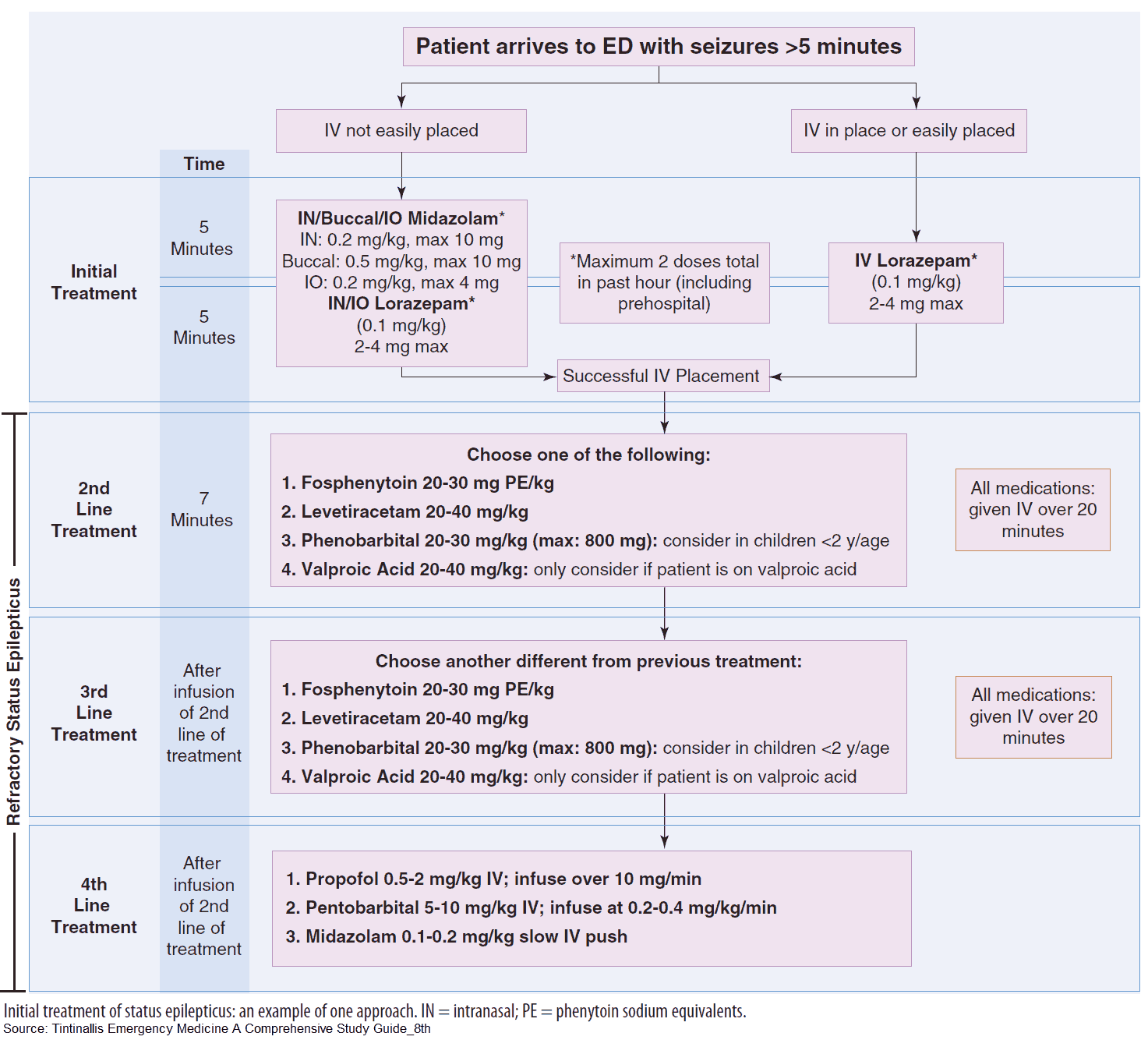

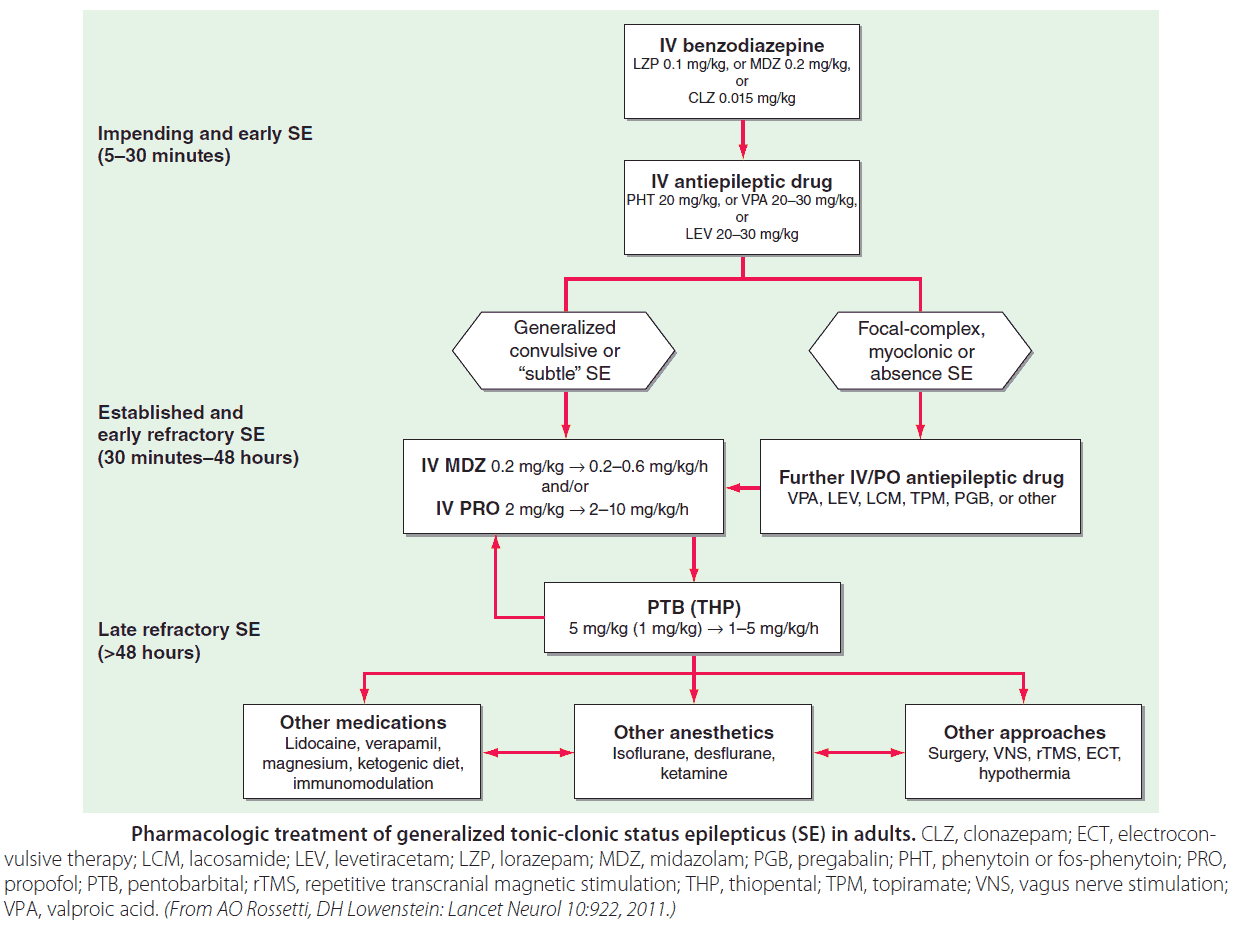

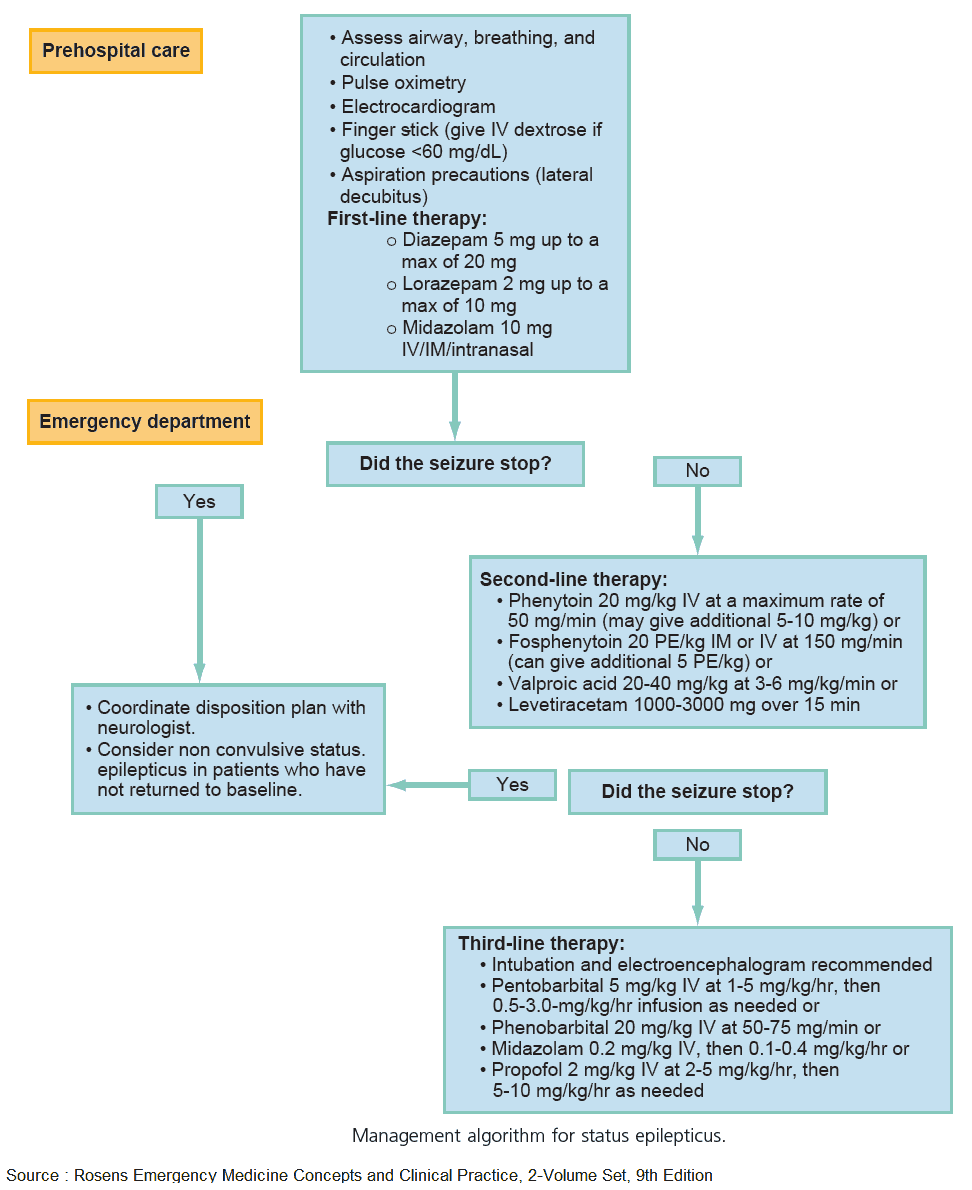

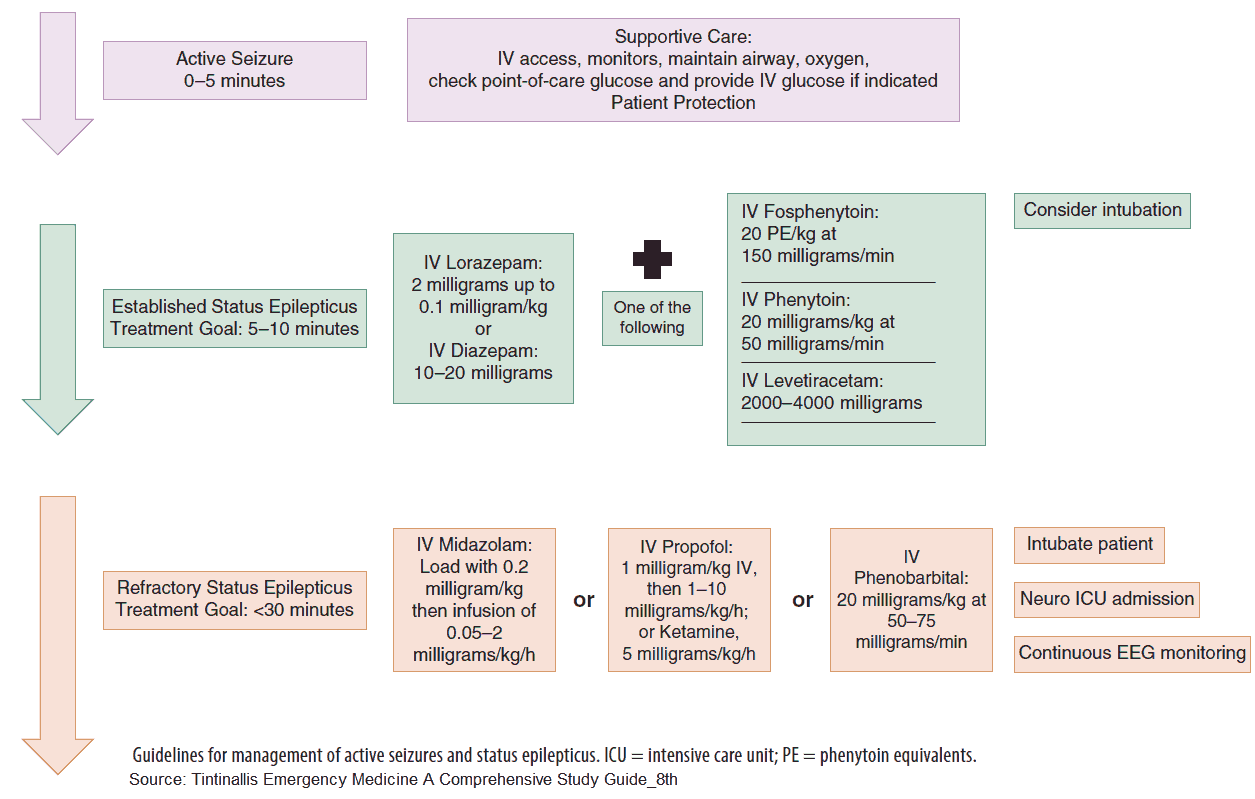

Treatment of status epilepticus

Status, as it is known, is defined as continuous seizure activity for over 5 minutes (some still define status as seizure activity lasting over 30 minutes). It can lead to rhabdomyolysis, lactic acidosis, aspiration pneumonitis, and respiratory failure. Neuronal death can occur after 30 to 60 minutes of continuous seizure activity. Treatment should start with 0.2 mg/kg of diazepam, followed by 20 mg/dk of phenytoin.