Table of Contents

Sensory neurologic deficits / abnormalities include:

- Hyperesthesias (increased pain, touch, or vibration)

- Hypalgesia (decreased sensitivity to painful stimuli)

- Paresthesia (abnormal sensation of the skin like tingling, pricking, chilling, burning, numbness)

- Anesthesia (complete loss of pain, temperature, touch, and vibration sense)

Muscle weakness or abnormal sensation can result from disease occurring anywhere along the pathway from the skin or muscle to the brain and back. Such pathologic processes are outlined below.

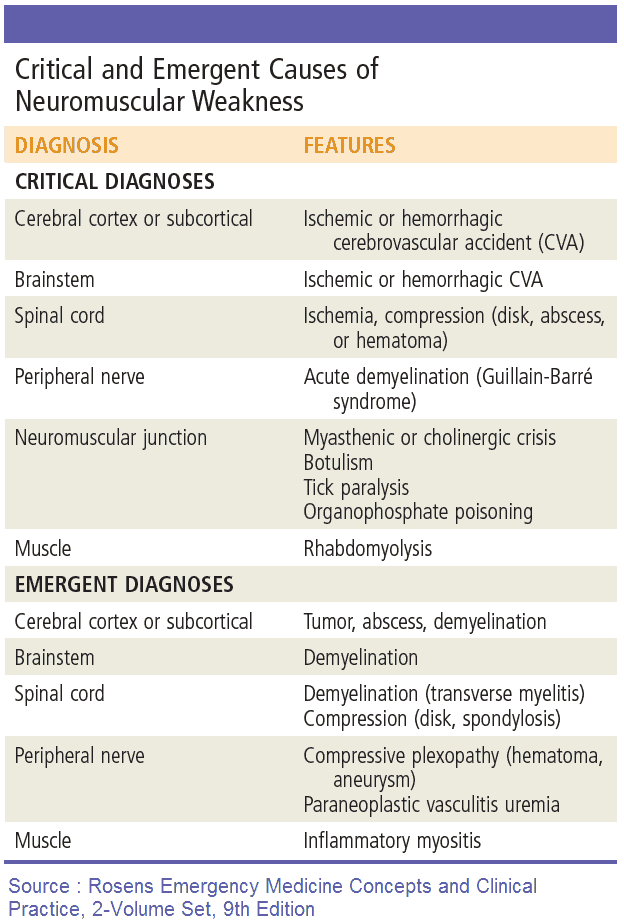

Causes and Differential Diagnosis of Sensory and/or Motor Neurologic Deficits

Muscle

Muscle diseases that can cause sensory and/or motor neurologic deficits include:

- Drugs: steroids, penicillamine, and procainamide.

- Dystrophy: Duchenne, Becker’s, limb girdle, and facioscapulohumeral.

- Endocrine: Cushing’s syndrome, thyrotoxicosis, myxedema, and hyperparathyroidism.

- Infection: bacterial (Clostridium welchii), viral (influenza), and parasitic (trichinosis).

- Inflammation: polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and sarcoidosis.

- Metabolic: periodic paralyses, McArdle’s disease, and mitochondrial myopathy.

- Myotonia: myotonia dystrophica and myotonia congenita (Thomsen’s disease).

- Toxin: alcohol.

- Tumor: sarcoma and paraneoplastic syndrome.

Neuromuscular junction

Neuromuscular junction diseases that can cause sensory and/or motor neurologic deficits include:

- Myasthenia gravis

- Lambert-Eaton syndrome

- Clostridium botulinum infection

Peripheral nerves

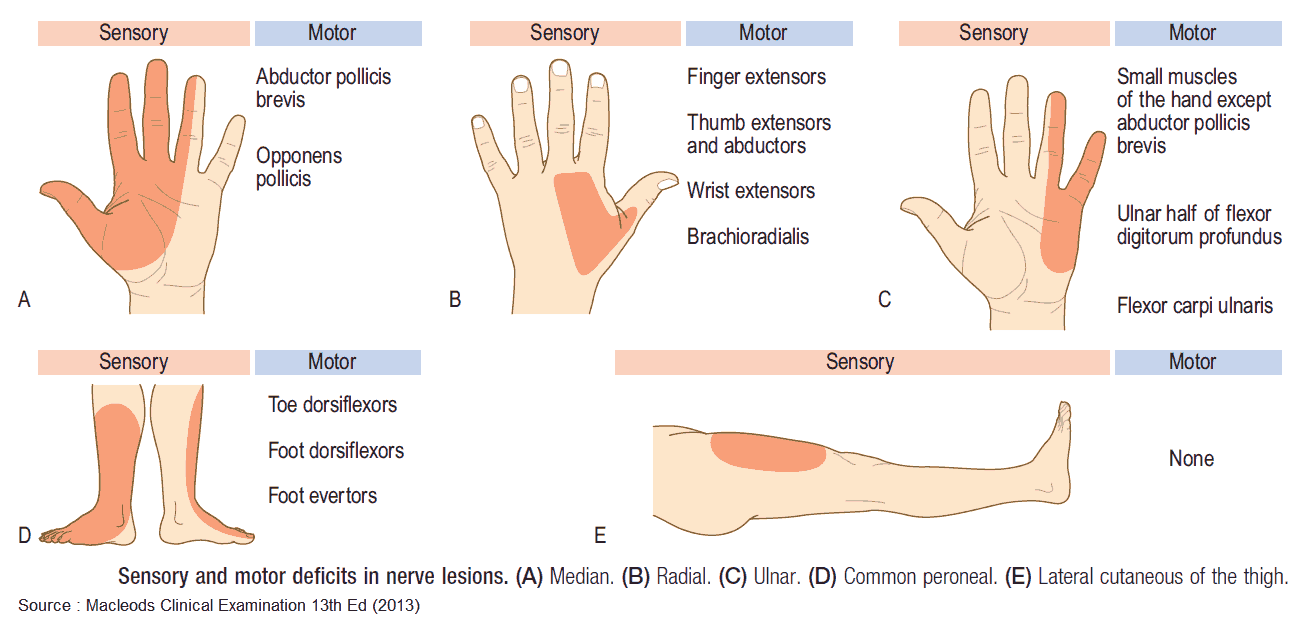

Peripheral nerve diseases that can cause sensory and/or motor neurologic deficits are grouped by the number of nerves affected.

Mononeuropathy

In mononeuropathy, only one peripheral nerve is involved. Consider:

- Trauma.

- Entrapment: carpal tunnel syndrome and meralgia paraesthetica.

- Stretching: ulnar nerve lesion if there is an increased carrying angle at the elbow.

- Tumor: neurofibromatosis.

Mononeuritis multiplex

In mononeuritis multiplex, two or more individual nerves are affected. The differential diagnosis includes the following:

- Connective tissue disease: polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

- Infection: leprosy, herpes zoster, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- Inflammation: sarcoid.

- Metabolic: diabetes mellitus (DM) and amyloid.

- Tumor: infiltration, paraneoplastic syndrome, and neurofibromatosis.

Peripheral neuropathy (polyneuropathy)

Peripheral neuropathy is polyneuropathy causing a symmetrical deficit that is most marked distally. The differential diagnosis includes the following:

- Connective tissue disease: PAN, SLE, and RA.

- Drugs: nitrofurantoin, metronidazole, and vincristine.

- Infection: leprosy, HIV, syphilis, and diphtheria.

- Inflammation: Guillain-Barré syndrome.

- Inherited: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and Refsum’s disease.

- Metabolic: diabetes, renal failure, porphyria, and amyloid.

- Toxins: alcohol and lead.

- Tumor: paraneoplastic syndrome and paraproteinemias.

- Vitamin deficiency: thiamine (B1), niacin (B3), and vitamin B12.

Brachial or lumbar plexus

Brachial or lumbar plexus disorders that can cause sensory and/or motor neurologic deficits include:

- Compression: cervical rib.

- Idiopathic: neuralgic amyotrophy.

- Metabolic: DM.

- Trauma: birth injury (Erb’s and Klumpke’s palsies) and motorbike accidents.

- Tumor: malignant infiltration.

Spinal nerve root

Spinal nerve roots disorders can cause sensory and/or motor neurologic deficits. Spinal nerve roots may be disrupted by the following:

- Infection (e.g., pyogenic meningitis and syphilis).

- Prolapsed intervertebral disc.

- Spinal stenosis.

- Spondylosis.

- Tumor.

- Vertebral fracture dislocation.

Anterior horn cell

The anterior horn cell may be damaged by the following:

- Motor neuron disease-amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

- Poliomyelitis.

Spinal cord

Spinal cord disorders that can cause sensory and/or motor neurologic deficits include:

- Degeneration: osteoarthritis.

- Infection: abscess, HIV, tuberculosis (Pott’s disease), syphilis.

- Inflammation: multiple sclerosis (MS), sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis (atlantoaxial subluxation).

- Metabolic: Paget’s disease.

- Trauma: including radiotherapy and prolapsed intervertebral disc.

- Tumor: metastases, neurofibroma, meningioma, glioma, and ependymoma.

- Vascular: anterior spinal artery occlusion, dissecting aortic aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, and vasculitis (PAN).

- Vitamin deficiency: subacute combined degeneration of the cord (vitamin B12).

- Others: syringomyelia, spina bifida, and motor neuron disease.

Cerebellum

Cerebellum disorders that can cause sensory and/or motor neurologic deficits include:

- Endocrine: hypothyroidism.

- Hereditary: Friedreich’s ataxia and ataxia telangiectasia.

- Infection: abscess and postencephalitis miliary TB.

- Inflammation: multiple sclerosis.

- Toxic: alcohol, lead, and phenytoin.

- Trauma: “punch-drunk” syndrome.

- Tumor: metastases, acoustic neuroma, hemangioblastoma (von Hippel-Lindau disease), and paraneoplastic degeneration.

- Vascular: infarction, hematoma, and arteriovenous malformation (AVM).

Cerebral hemispheres

Cerebral hemispheres disorders that can cause sensory and/or motor neurologic deficits include:

- Degenerative disease.

- Hydrocephalus: primary or secondary.

- Infection: abscess, meningitis, encephalitis, HIV, malaria, rabies, tuberculosis, and syphilis.

- Inflammation: sarcoid, SLE, and MS.

- Metabolic: phenylketonuria and Wilson’s disease (basal ganglia).

- Toxic: alcohol, cocaine.

- Trauma.

- Tumor: primary or secondary.

- Vascular: infarction, hemorrhage or hematoma, AVM, and aneurysm.

- Vitamin deficiency: thiamine, niacin, and B12.

- Other disorders causing cerebral disturbance, such as carbon dioxide narcosis and hepatic encephalopathy.

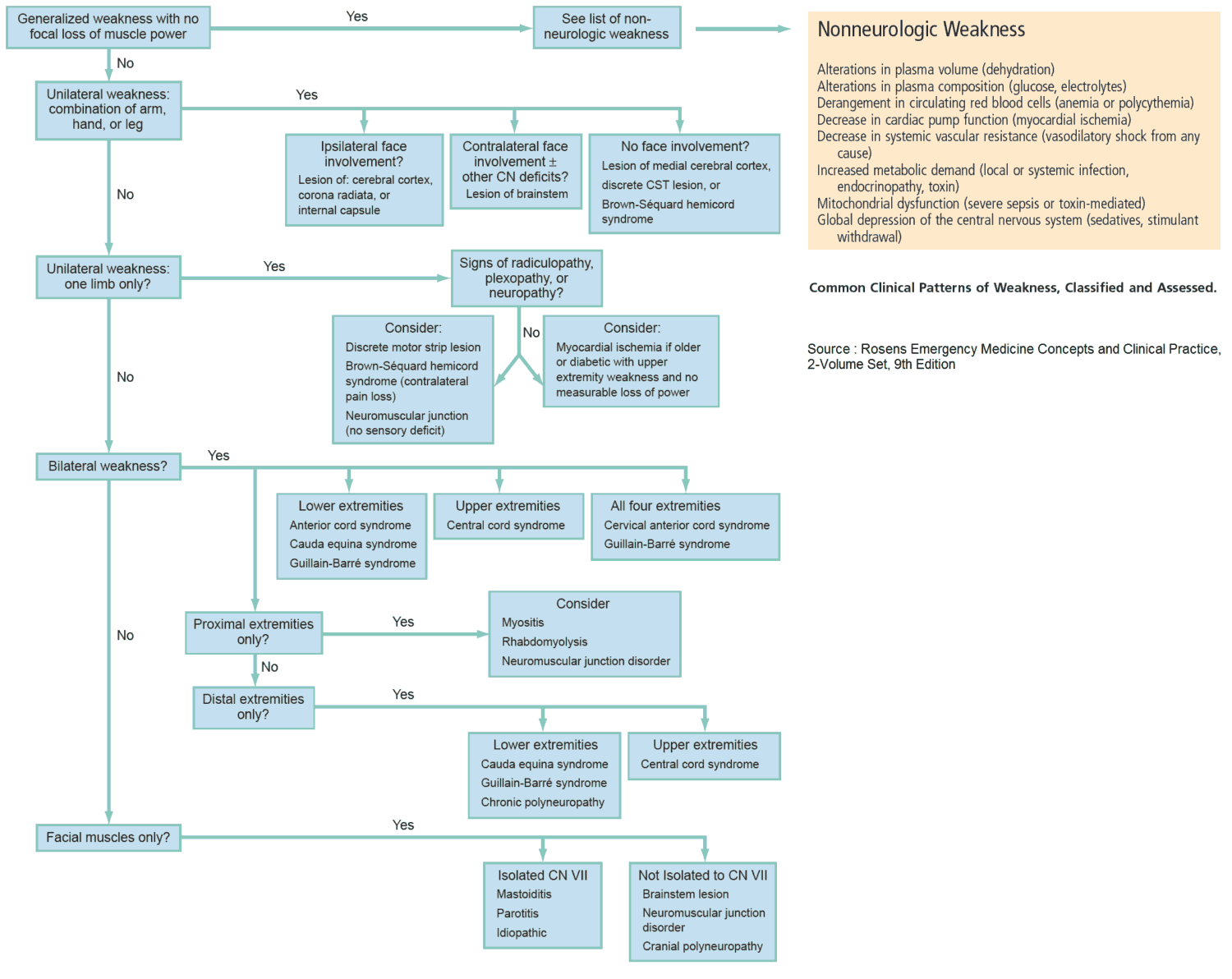

Symptoms and History in the Patient with Sensory and/or Motor Neurologic Deficits

It is often a daunting prospect to be faced with a patient with neurologic symptoms or signs. However, despite the vast number of potential underlying pathologies, a lesion at a particular point in the pathway between brain and muscle or skin will always produce the same clinical signs regardless of the cause. There are five important aspects to consider in the history.

1. Onset of Sensory and/or Motor Neurologic Deficit

Sudden onset usually indicates a vascular problem such as infarction, hemorrhage, or hematoma. Lesions due to trauma, MS, abscess, acute prolapsed disc, and myelitis can also develop rapidly.

An insidious onset is more typical of cervical spondylosis, motor neuron disease, neoplasm, myopathy, and syringomyelia.

2. Precipitants of Sensory and/or Motor Neurologic Deficit

- Trauma may result in muscular and neurologic deficits.

- Intercurrent illness (particularly infection), or Drugs (aminoglycosides or penicillamine) can precipitate acute myasthenia.

- MS may relapse during the puerperium and symptoms may be exacerbated by exertion, hot weather, or after a hot bath.

3. Development of Sensory and/or Motor Neurologic Deficit

Many lesions cause gradually progressive, unremitting disease/deficit, including tumor, motor neuron disease, hereditary ataxias, and degenerative brain diseases.

Intermittent deficits can be due to transient ischemic attacks, epilepsy, migraine, and myasthenia gravis.

MS is characterized by the development of different lesions which are dissociated in time and site.

Symptoms and signs due to trauma or vascular events may slowly improve with time or remain static following the initial event.

4. Pattern of Sensory and/or Motor Neurologic deficit

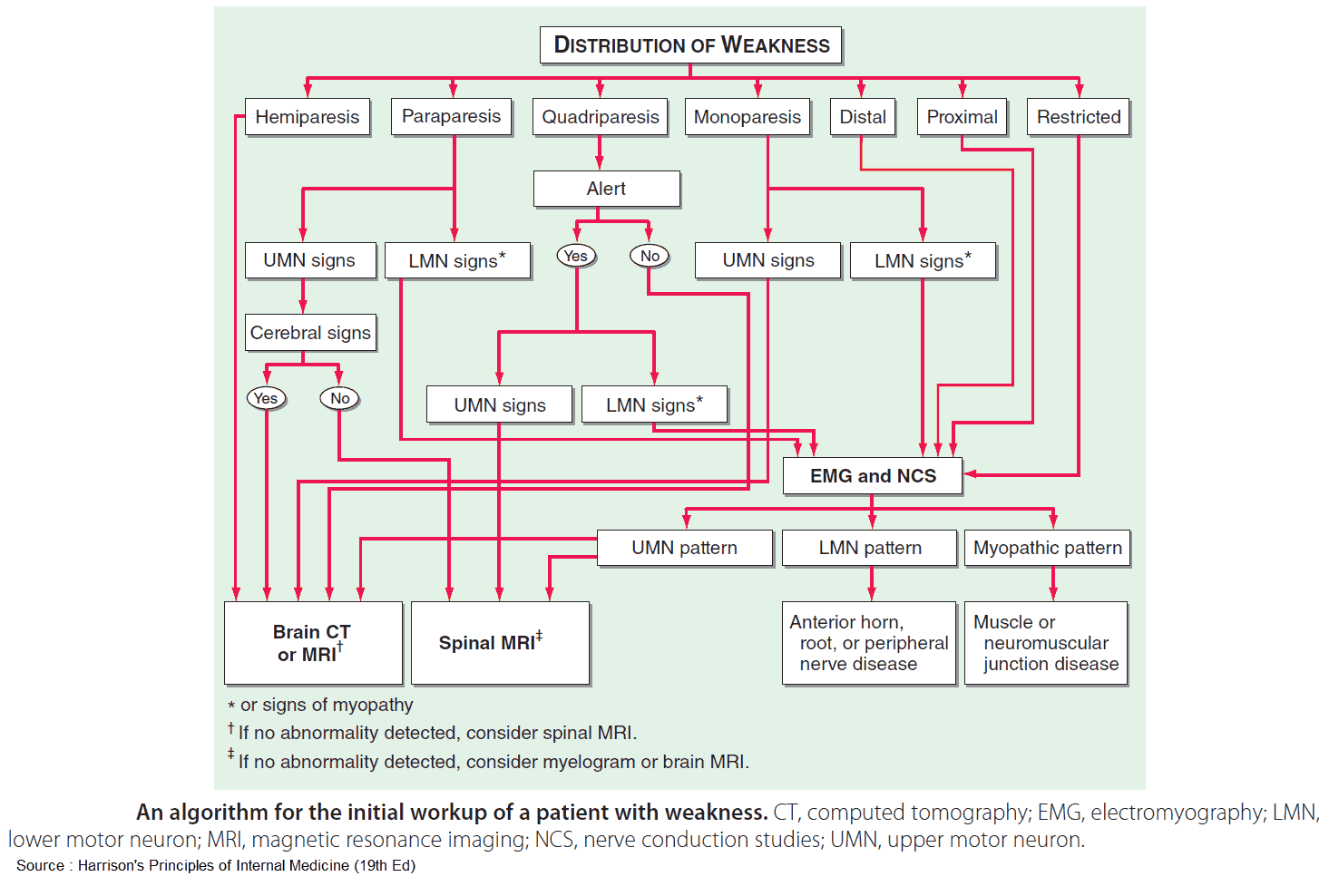

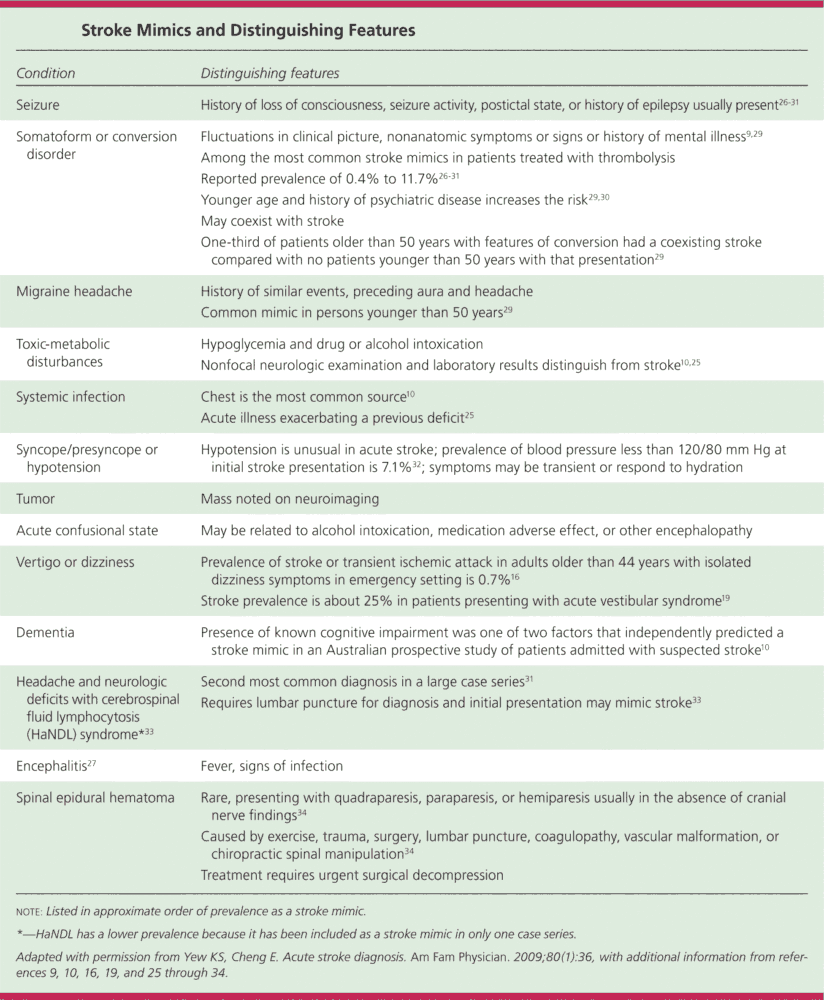

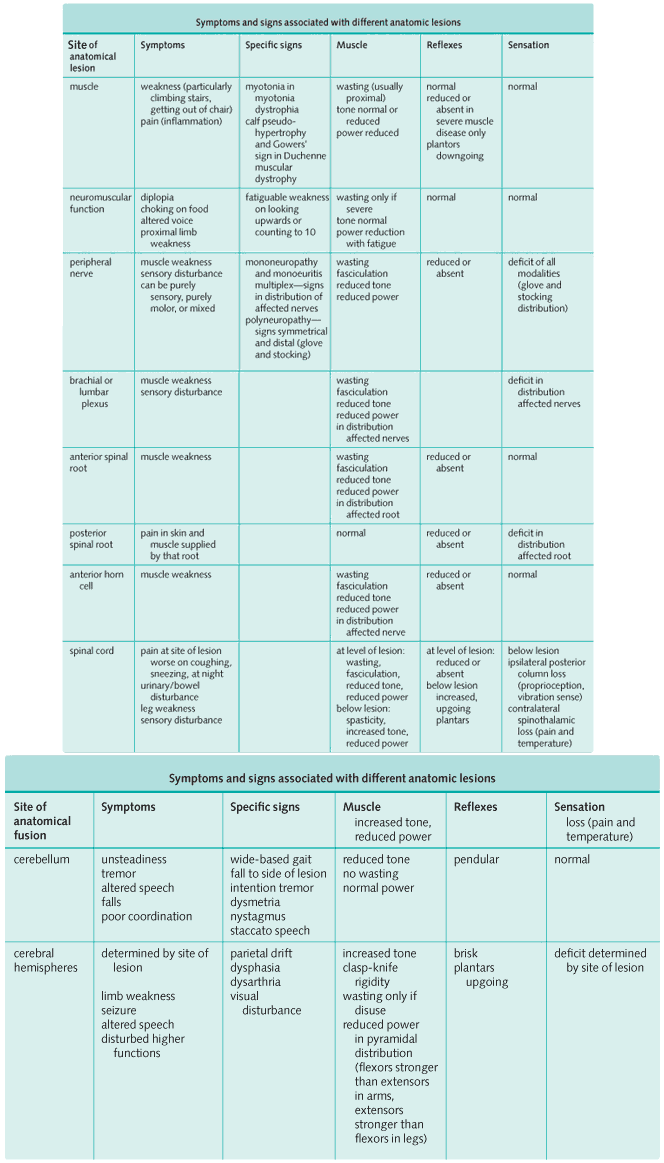

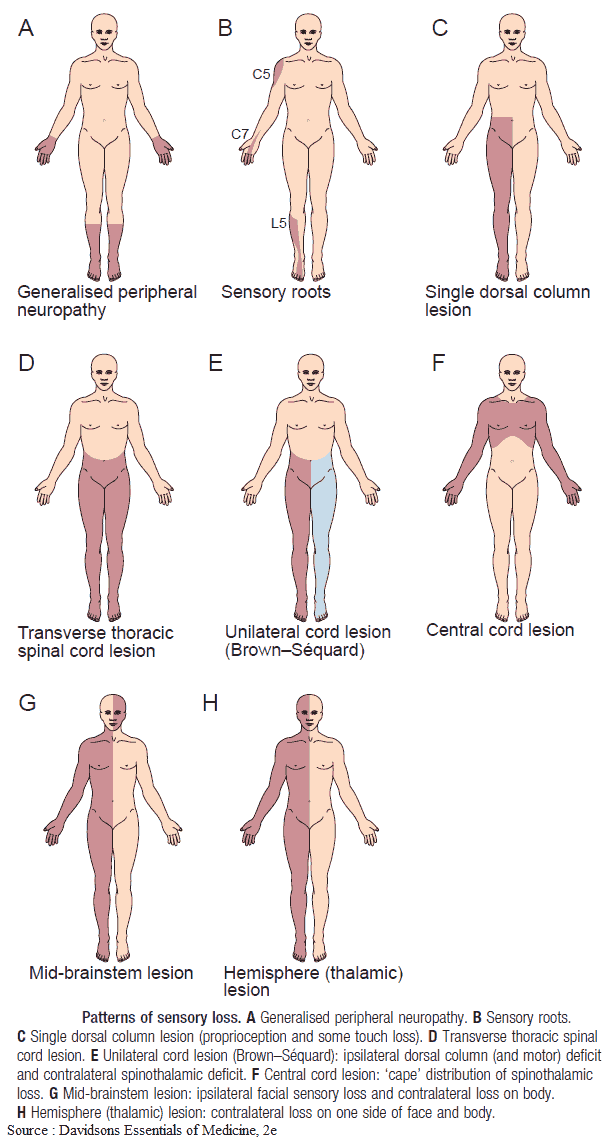

The image below summarizes characteristic symptoms and signs which arise as a consequence of a lesion at a specific site. If the neurologic abnormalities do not fit a specific pattern, consider MS, motor neuron disease, or paraneoplastic neuropathy.

5. Evidence of Cause of Sensory and/or Motor Neurologic deficit

The following factors provide evidence of cause:

- Family history: hereditary ataxias, phenylketonuria, neurofibromatosis.

- Drug history, including phenytoin (cerebellar signs), vincristine (peripheral neuropathy), penicillamine (myasthenia).

- Dietary history: intake of vitamins B1, B6 and B12.

- Alcohol history.

- Pre-existing illness, such as diabetes, hypertension (cerebrovascular disease), rheumatoid arthritis, or malignancy.

- History of trauma.

Examination and Signs in the Patient with Sensory and/or Motor Neurologic Deficits

When assessing a patient in clinic or hospital, a full neurologic examination should be performed. Remember the importance of vital signs, since blood pressure and pulse can help diagnose stroke, arrhythmias, and metabolic disorders.

However, in medical school examinations you will only be expected to assess a specific part of the system, such as the eyes, face, legs, arms, or gait. The most common neurologic short cases are peripheral neuropathy (usually due to DM), Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and MS, but be prepared for anything!

The clinical examination should aim to answer three questions.

- Firstly, where is the anatomic site of the lesion or lesions?

- Secondly, is there anything to suggest the underlying pathologic process?

- Finally, what disability does the patient have as a consequence of the neurologic deficit?

1. Where is the lesion?

The neurologic exam, with particular attention to the cranial nerves, can help localize the lesion. Inspection of the patient’s movements on first meeting can lead to the diagnosis-for instance, how the patient is able to move his/her feet or shake hands.

From the moment you meet the patient, watch like a hawk. Can the patient lift up the arm? Can the patient let go of your hand (myotonia)? Watch how the patient undresses or gets on to the bed. Any severe deficit will often become apparent before you even lay hands on the patient. Examine the area of interest very carefully.

The Image above should help you identify where the anatomic lesion is likely to be on the basis of those neurologic abnormalities present.

2. What is the underlying cause?

Once the site of the lesion is identified, think of the differential diagnosis as outlined at the beginning of this article. Are there any clues around the patient? Look for diabetic drinks (for peripheral neuropathy or amyotrophy).

If the patient is young, looks well, and is sitting in a wheelchair, MS is the most likely diagnosis.

An elderly patient with a hemiparesis is most likely to have had a stroke. Is there a blood pressure chart?

Look at the patient’s face for myotonic facies (myotonia dystrophica), Cushing’s syndrome (proximal myopathy), or hypothyroidism (myopathy or cerebellar dysfunction).

Does the patient have neurofibromatosis (spinal cord or peripheral nerve lesions) or connective tissue disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis (entrapment mononeuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, or peripheral neuropathy)? Is there a cervical rib?

3. What disability does the sensory and/or motor neurologic deficit cause?

The most important thing for the patient is not locating the anatomic site of the lesion but what that lesion prevents the patient from doing. This is an important part of the examination and is often missed.

Think what tasks the affected part of the body normally performs, and ask the patient to show you how he or she manages, such as doing up buttons (for peripheral neuropathy), brushing hair, or standing out of a chair (for proximal myopathy).

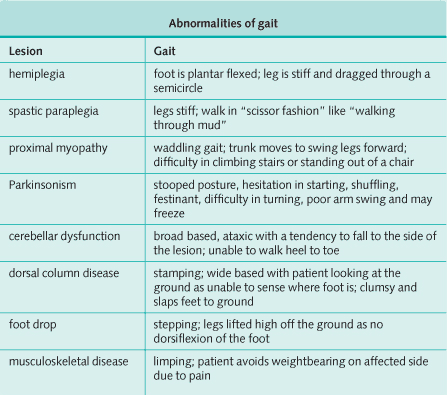

Watching the patient walk can give useful information (see image bellow).

Investigating and Diagnosing the Patient with Sensory and/or Motor Neurologic Deficits

The pathway of investigation is very much determined by findings on the history and clinical examination. The following tests may be useful but each patient will require only those relevant to their presentation:

- Complete blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate: reactive picture in inflammation, infection, and neoplasm, and raised mean corpuscular volume in vitamin B12 deficiency and alcohol abuse.

- Metabolic panel: raised urea and creatinine in renal failure, potassium high or low in periodic paralyses.

- Serum calcium: raised in hyperparathyroidism.

- Serum glucose: raised in DM.

- Liver function tests: raised γ-glutamyltransferase in alcohol abuse, raised alkaline phosphatase in Paget’s disease, and deranged transamines in metastases, infection, and Wilson’s disease.

- Thyroid function tests: hyper- or hypothyroidism.

- Creatine kinase: markedly raised in muscle inflammation and muscular dystrophies.

- Autoantibodies: RA, SLE, and PAN.

- Serology: HIV, herpes, and syphilis where appropriate.

- Immunoglobulins: paraproteinemias.

- Lumbar puncture: microscopy (infection and malignancy), culture and sensitivity (infection), glucose (reduced in bacterial and tuberculous meningitis), protein (markedly raised in tuberculous meningitis, acoustic neuroma, Guillain-Barré syndrome, Behçet’s syndrome, and Froin’s syndrome), oligoclonal bands (raised in MS and also in SLE, syphilis, sarcoidosis, and Behçet’s syndrome), and xanthochromia (yellow cerebrospinal fluid due to hemoglobin breakdown products) indicating recent subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Electroencephalogram: may indicate structural cerebral pathology and is characteristic in herpes simplex encephalitis.

- Electromyogram: primary muscle disease (typical changes in myotonia and myasthenia); it also shows denervation but not its cause.

- Nerve conduction studies demonstrate peripheral neuropathies.

- Radiology: plain radiographs may demonstrate degenerative and destructive bone lesions and fractures; computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spine are extremely useful in diagnosing and localizing central lesions; myelography can be useful in demonstrating compressive cord lesions but this technique has been largely superseded by CT scans and MRI.

- Visual evoked potentials: demonstrate previous retrobulbar neuritis in MS.

- Biopsy: if the diagnosis is in doubt, despite history, examination, and noninvasive procedures. Muscle, nerve, and brain biopsies can be performed to give a definitive histologic diagnosis.