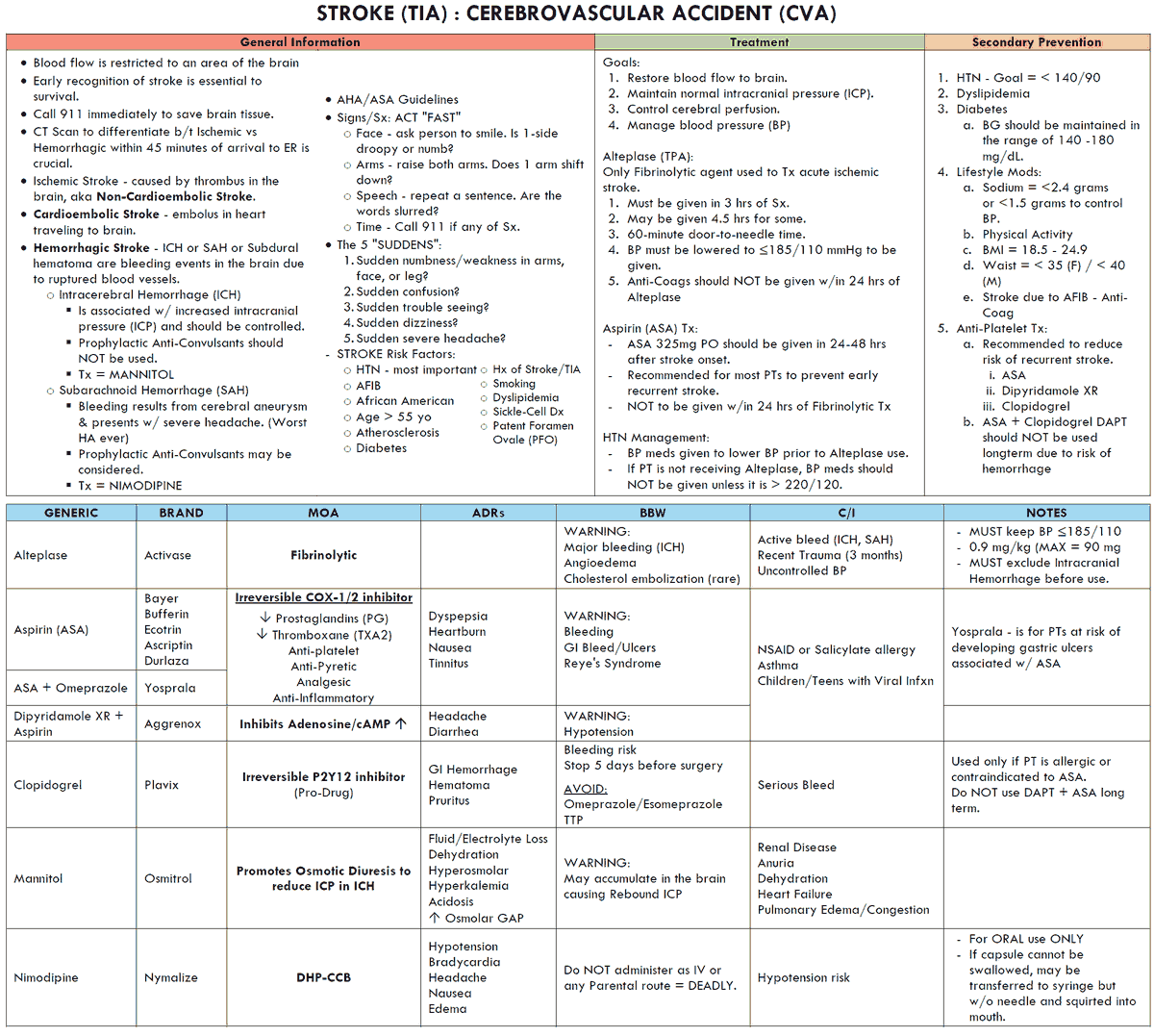

Table of Contents

A stroke is a focal neurologic deficit due to a vascular lesion that lasts for more than 24 hours. About 80% are due to infarction secondary to thrombosis or embolism, and 20% are due to intracerebral hemorrhage.

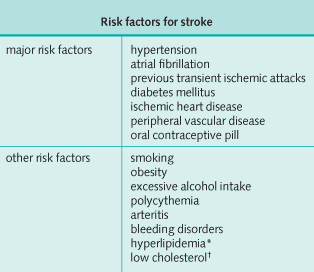

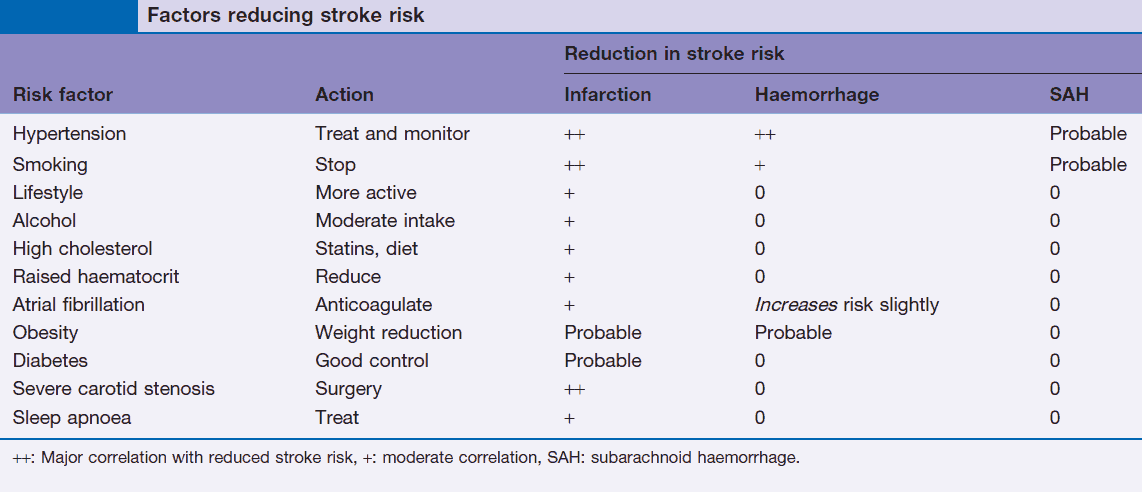

The overall incidence is about 150 in 100,000 but rises with age so that the incidence at 75 years is 1000 in 100,000. It is the third leading cause of death in the U.S. Risk factors for stroke are summarized in the image below.

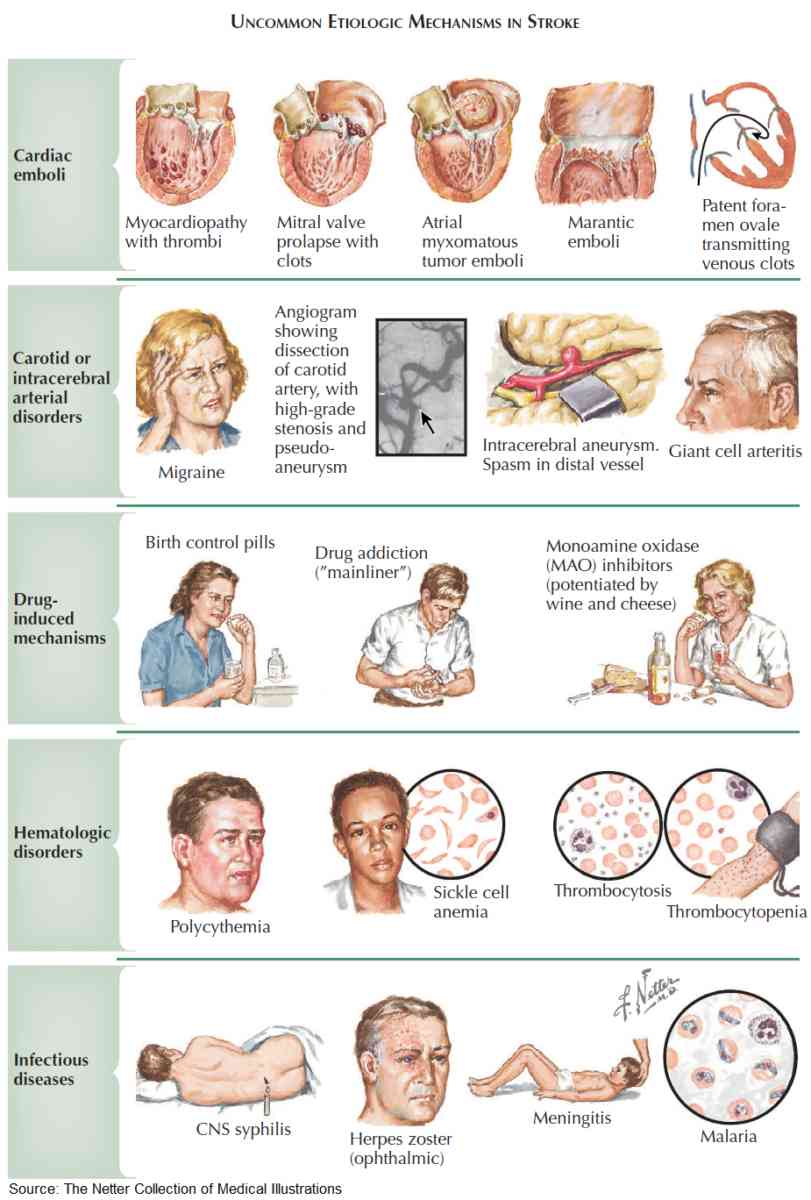

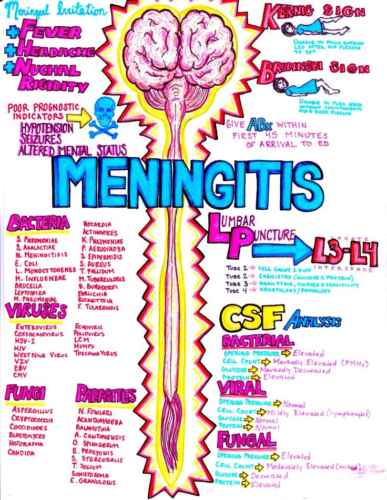

The main cause of thrombotic strokes are thromboembolism from arteries and emboli from the heart. Uncommon causes of thrombosis are vasculitis, polycythemia rubra vera, and meningovascular syphilis. Thrombus in situ may also occur following hypotension.

Cerebral hemorrhage is usually due to rupture of microaneurysms in perforating arteries or intracerebral vessels. Less common causes of hemorrhagic stroke include hemorrhage, tumor, abscess, or secondary to blood dyscrasias.

The sudden onset of any symptom usually suggests either a vascular or neurologic etiology.

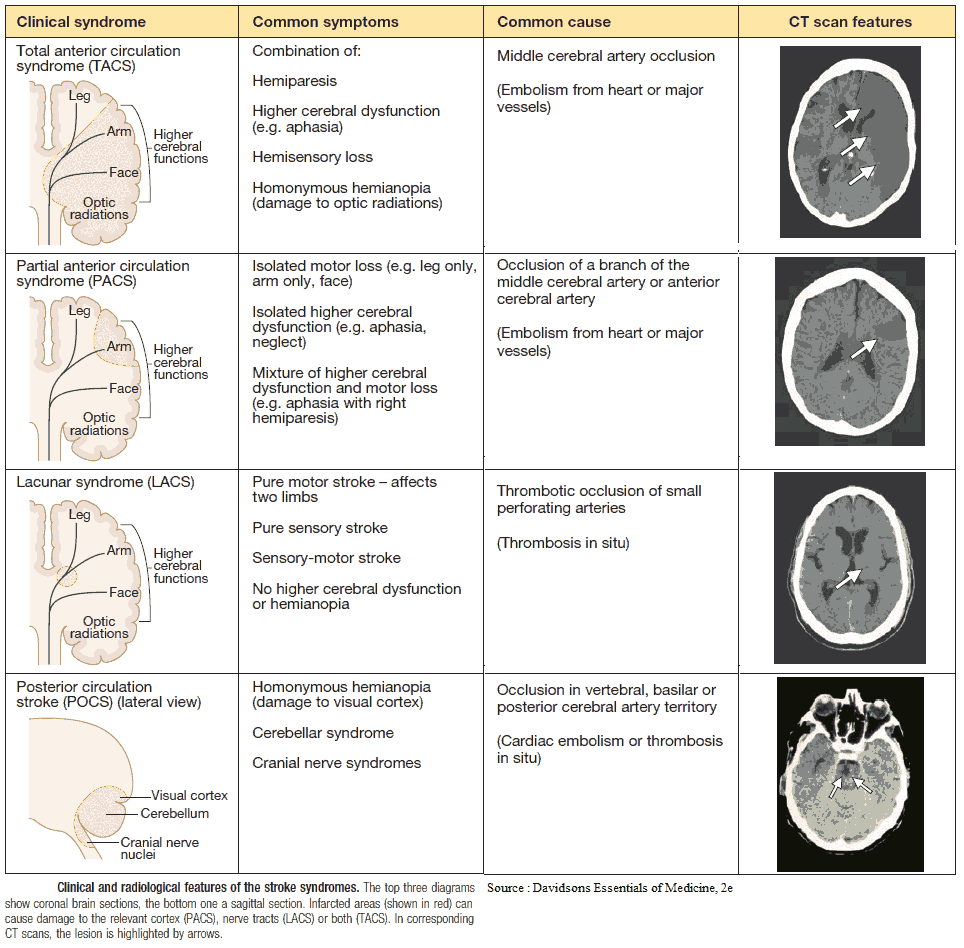

Clinical Features of Stroke

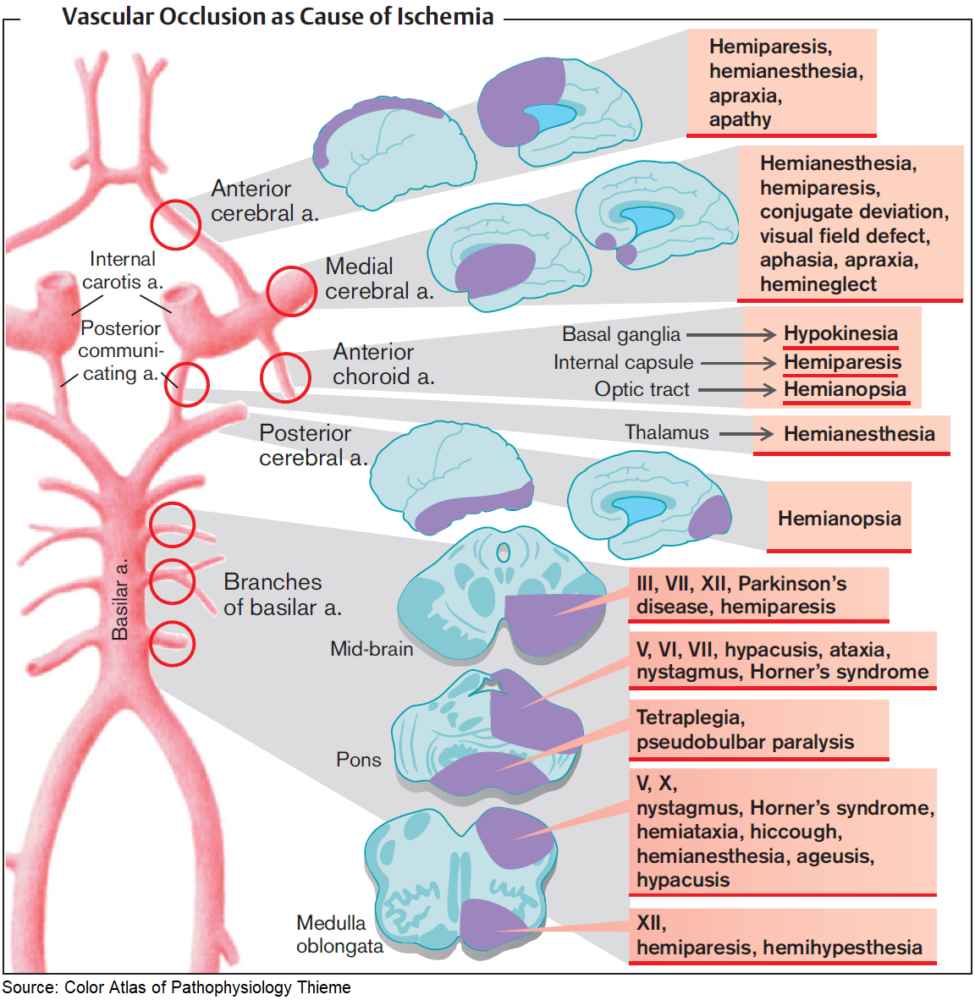

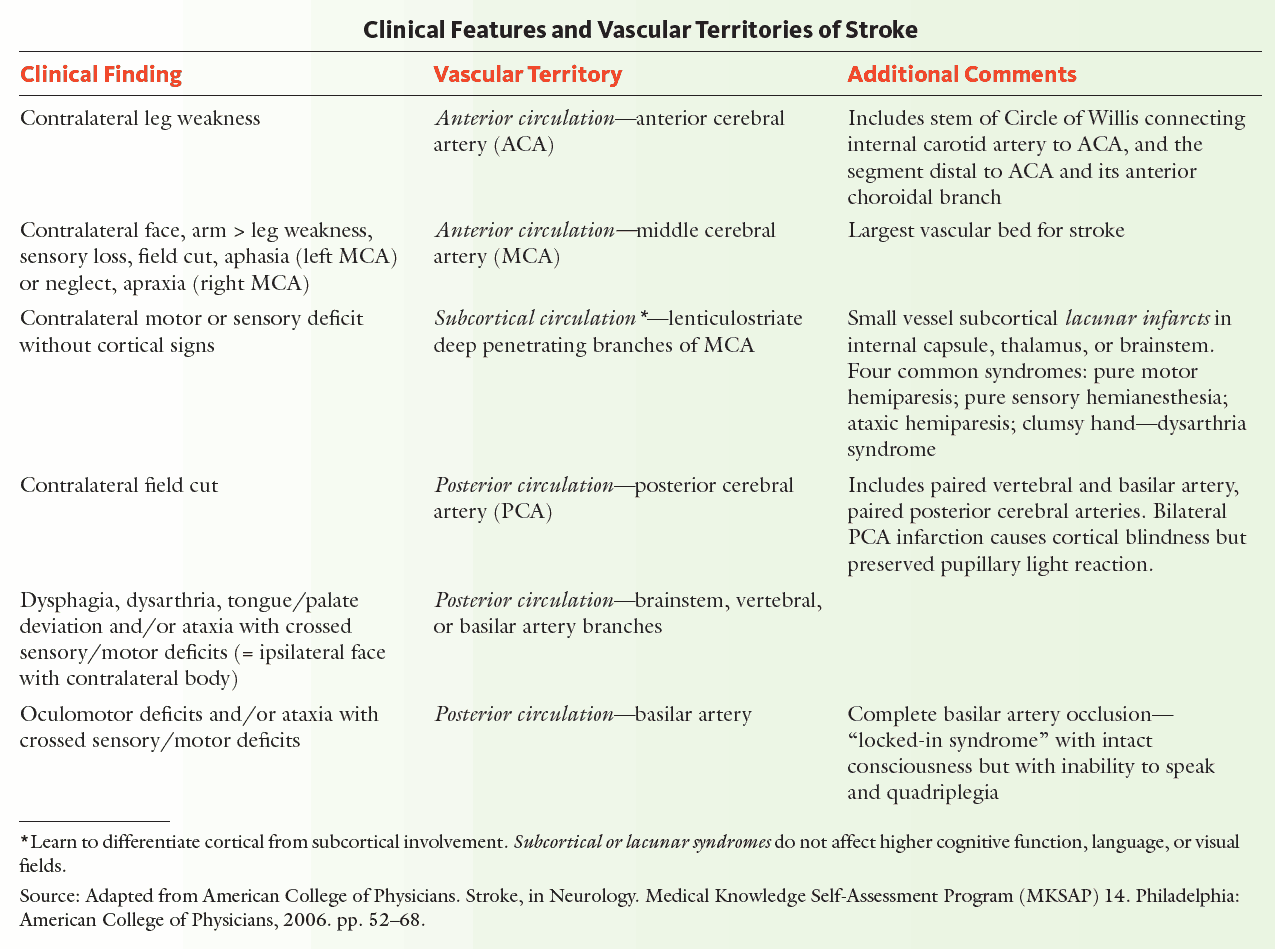

Signs and symptoms usually appear rapidly, whereas a gradual progression over days suggests a tumor. Clinical features relate to the distribution of the affected artery, although in practice this may not be clear-cut due to collateral circulation and the development of cerebral edema. The most common presentation is hemiplegia due to infarction of the internal capsule.

Types of infarction

Cerebral hemisphere infarcts

Cerebral hemisphere infarcts may be classified by vascular territory:

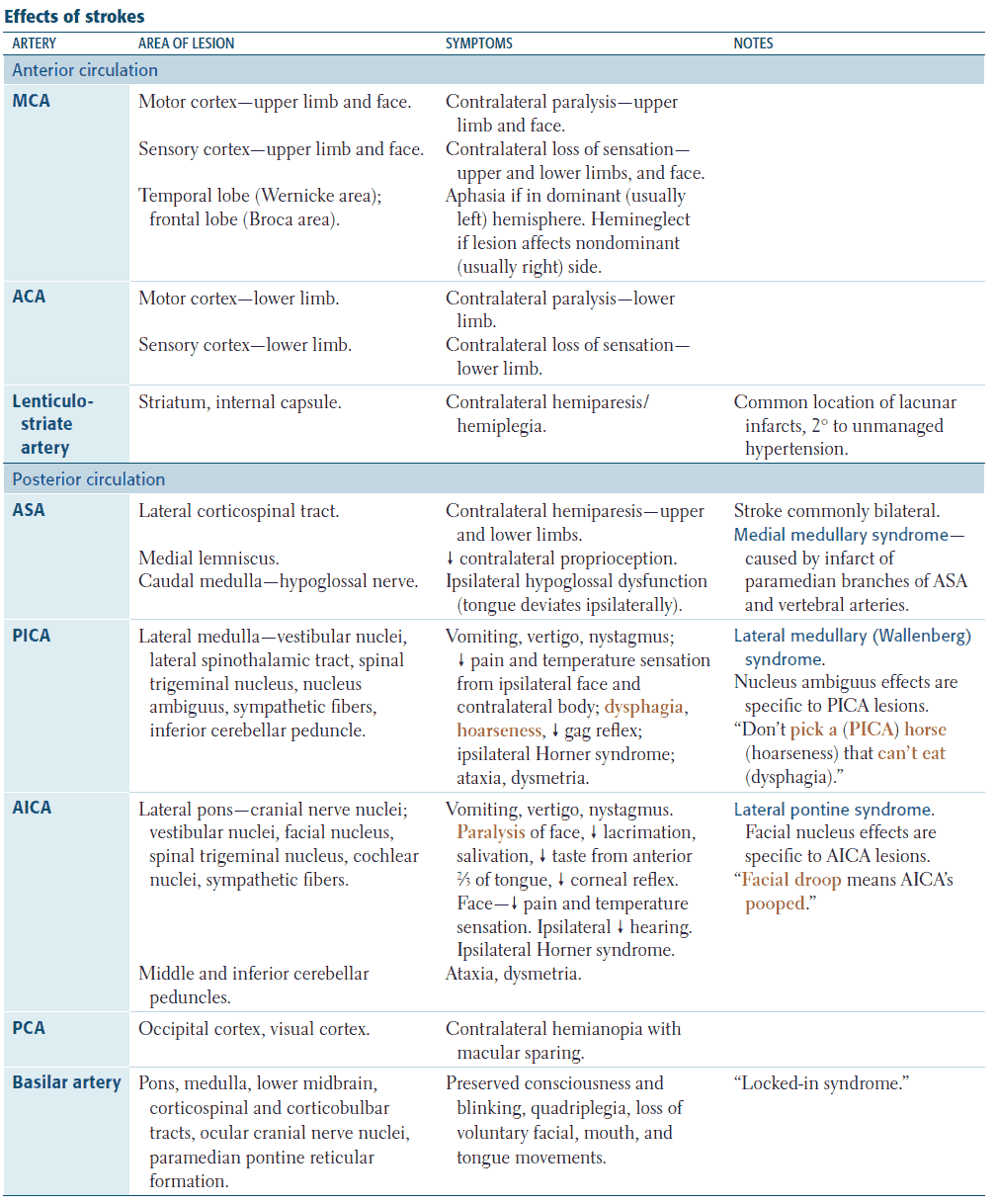

- Anterior cerebral artery infarcts: proximal to the medial striate branch, they cause contralateral hemiplegia; distal to the medial striate branch, they cause contralateral paralysis with sparing of the arm and face.

- Middle cerebral artery infarcts: causes contralateral hemiplegia, often sparing the leg, and hemianopia. Aphasia is present if the dominant hemisphere is affected.

- Posterior cerebral artery infarcts: causes contralateral hemianopia.

- Motor signs are upper motor neuron.

Lacunar strokes

Lacunar strokes are due to small areas of infarction usually occurring around the basal ganglia, thalamus, and pons. Clinical features include:

- pure motor or sensory signs

- mixed motor and sensory picture

- ataxia

- dysarthria

They may also be asymptomatic and found at post-mortem examination.

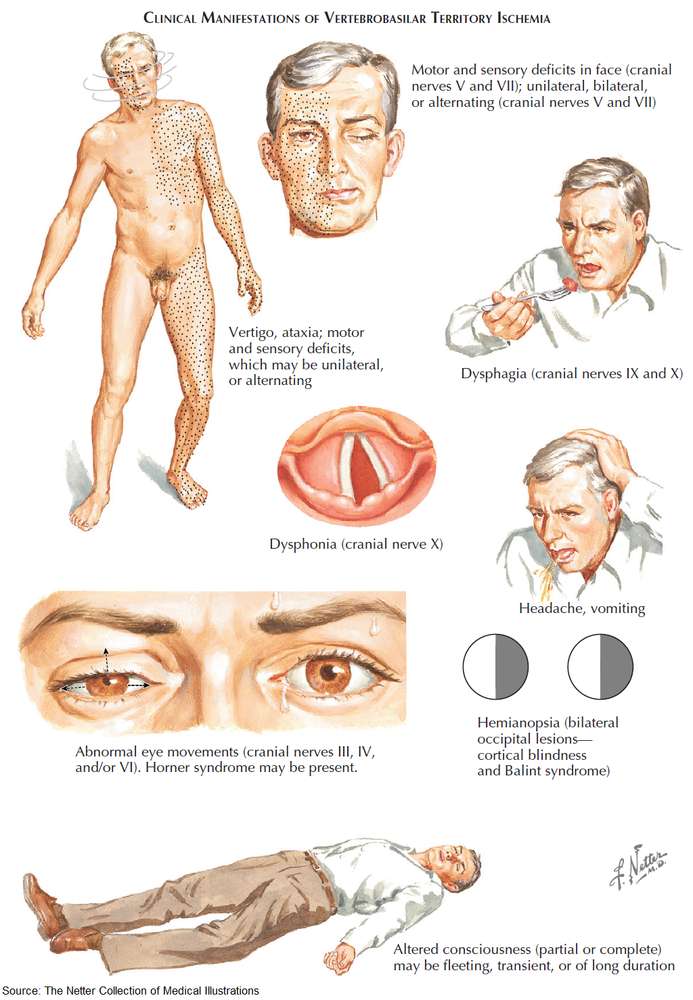

Brainstem infarcts

Clinical features include:

- hemi- or quadriplegia

- sensory loss

- diplopia

- facial weakness and numbness

- nystagmus

- dysphasia

- coma due to damage to the reticular formation

- locked-in syndrome from upper brain-stem infarction (the patient is conscious but unable to respond)

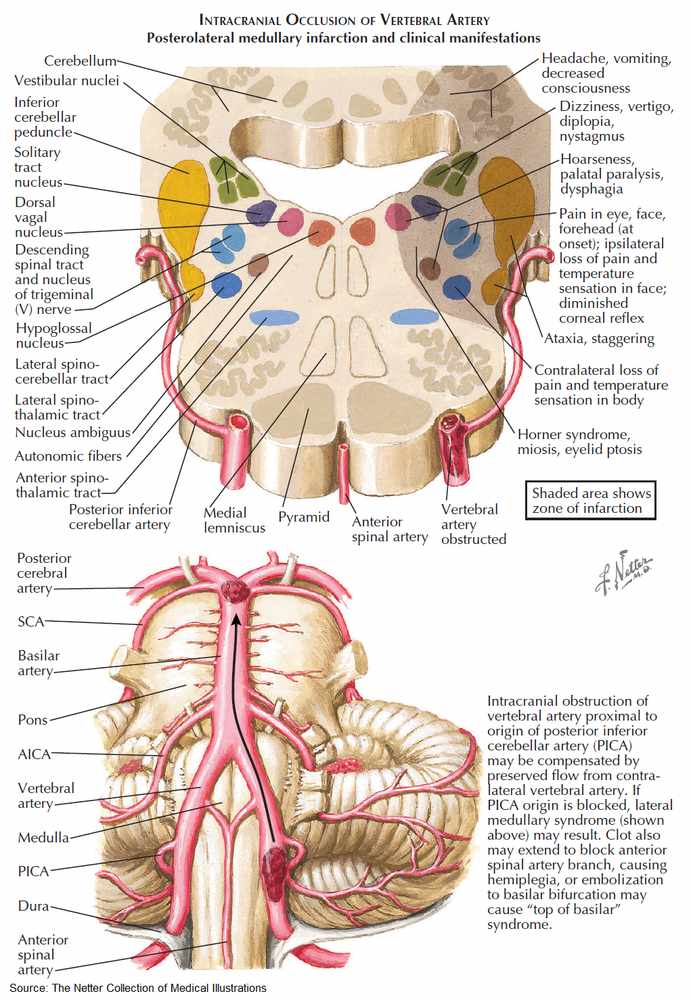

The most common brainstem vascular syndrome is lateral medullary syndrome (Wallenberg’s syndrome), which is due to thromboembolism of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. The patient presents with sudden vertigo and vomiting. Ipsilateral signs include 9th and 10th nerve lesions, Horner’s syndrome, spinothalamic sensory loss in the face, diplopia, and cerebellar signs in the limbs. Contralateral signs include spinothalamic sensory loss in the body.

Investigation and Diagnosis of Stroke

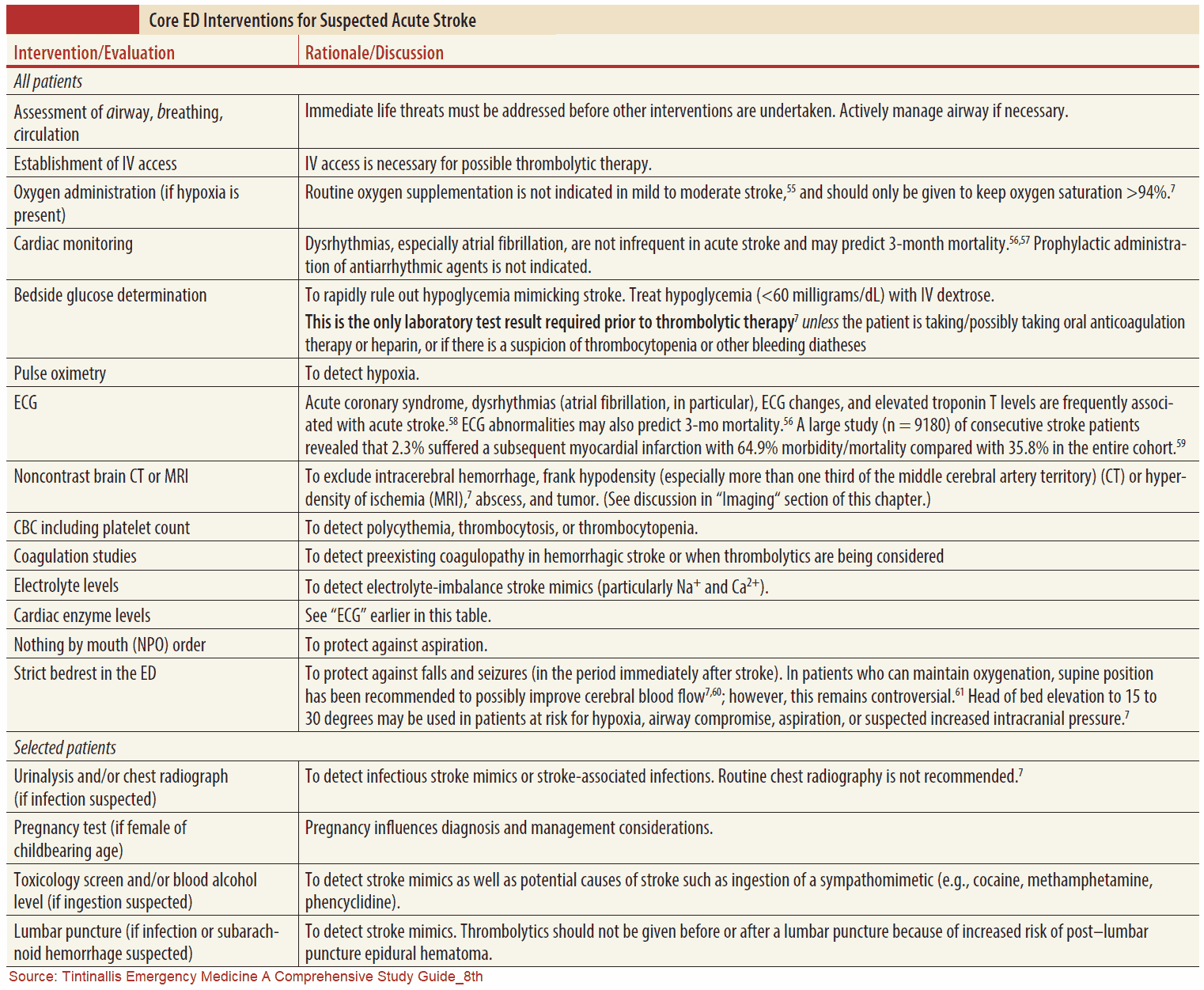

The following investigations should be performed in patients who have suffered a stroke:

- Complete blood count (CBC): polycythemia or thrombocytopenia.

- Coagulation studies: bleeding disorders.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): giant cell arteritis.

- Blood glucose: hyper- or hypoglycemia may lead to impaired consciousness.

- Chest x-ray (CXR): primary tumor; left atrium enlarged with mitral stenosis.

- Syphilis serology.

- Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan: this will distinguish between hemorrhagic and ischemic infarction if done within 2 weeks and should be done acutely to rule out hemorrhage whenever thrombolytics are considered; also aids diagnosis of other conditions in cases of uncertainty, such as tumor or subdural hematoma; should always be performed in cerebellar stroke as hematoma requires urgent evacuation.

- MRI: can show ischemia within 15-30 minutes. Different types of MRI can be performed, including MR angiography (MRA), depending on the information needed.

- Carotid duplex scan: stenoses.

Treatment and Management of Stroke

Prevention

Risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), high cholesterol, and atrial fibrillation should be identified and managed appropriately.

Following stroke, the blood pressure may be high for some days, and a decision about the use of antihypertensive drugs is not usually made for about 2 weeks.

Cholesterol should be lowered to reduce coronary risk because myocardial infarction is the major cause of death during the period following the acute stage of stroke or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs). Anticoagulation should be considered for patients with atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic stroke.

If there is a severe internal carotid artery stenosis (of more than 70%) and the patient has had TIAs within the past 6 months, endarterectomy should be considered.

Treatment

If the patient is unconscious or severely impaired, a decision about the most appropriate degree of intervention needs to be made in liaison with relatives and the patient, if possible. Factors to consider include prognosis, quality of life, and the patient’s wishes.

Raised intracranial pressure should be suspected if the blood pressure rises, the pulse falls, and there is papilledema. An urgent CT scan should be considered.

If urgent noncontrast CT scan shows no hemorrhage, the patient should be treated with alteplase (recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator [rt-PA) up to 3 hours after the stroke. After 3 hours, the risk of giving the agent outweighs the benefits. The quicker the patient can be given the thrombolytic, the better the outcome in terms of long-term morbidity and mortality. Patients treated within the first 90 minutes had the best outcomes.

All blood pressure medications should be held in order to ensure proper brain perfusion. Increases in the ICP sometimes force the systemic blood pressure higher than normal. In the presence of an acute bleed, the ICP should be measured. For ischemic stroke, blood pressure should not be treated unless it is severe (>220 systolic or >120 diastolic). This is often true for up to 2 weeks following acute presentation as well.

Stroke patients should be on a low threshold for intubation. With altered mental status, aspiration is a risk. In addition, hyperventilation can help decrease ICP. Often the stroke will affect the respiratory drive itself, and mechanical ventilation is necessary in acute stabilization.

Hydration should be maintained, and this should be done parenterally if there is no gag reflex. The patient should be turned regularly to prevent pressure sores. If incontinent, urinary catheterization should be considered. Physical therapy will prevent contractures and hasten mobility. Speech therapy and occupational therapy are important later on.

Aspirin, 81-325 mg daily, or clopidogrel, 75 mg daily, for people with thrombotic stroke, reduces the rate of further strokes and vascular deaths. Complications (e.g., pneumonia, depression, and constipation) should be managed appropriately. Patients may also be started on another antiplatelet medication such as clopidogrel or dipyridamole, with or without continuing daily aspirin.

For patients who fail aspirin therapy by having another TIA or stroke while on the medication, a second antiplatelet medication should be started. Patients with atrial fibrillation who are not on anticoagulation should have heparin therapy started after any neurologic event.

Prognosis

Features associated with a poor prognosis include impaired consciousness, severe hemiplegia, incontinence, a defect in conjugate gaze, and increasing age. About 20-25% of patients with thromboembolic infarction and 75% of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage die at 1 month. Recurrent strokes are common. About a third of survivors make a complete recovery and a third are left with severe disability.

Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIA)

These are focal neurologic deficits due to vascular events that resolve within 24 hours with a complete clinical recovery. They are usually due to emboli from the carotid or vertebrobasilar arteries, but emboli may also arise from the heart or other vessels. The annual incidence is about 50 per 100,000.

Other possible causes are:

- Arteritis (e.g., giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa [PAN]

- Systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], syphilis, arterial trauma)

- Hematologic causes (e.g., polycythemia rubra vera and sickle cell disease)

Clinical Features of TIA

There is a sudden focal neurologic deficit, which gradually resolves over minutes or hours, leading to complete recovery within 24 hours. In the internal carotid artery territory, platelet emboli obstruct blood flow, leading to loss of function in part of the brain. The platelet aggregates then break up, restoring blood flow and hence function.

This may lead to dysphasia and dysarthria, contralateral hemiparesis, hemisensory loss, homonymous hemianopia, and ipsilateral amaurosis fugax. The latter is due to emboli passing through the retinal arteries, leading to a sensation of a curtain passing across the vision.

TIAs in the vertebrobasilar system may again result from emboli or from a pinching of the vertebral arteries by osteophytes arising from the cervical vertebrae. Symptoms include diplopia, vertigo, nausea and vomiting, ataxia, hemiparesis or hemisensory loss, tetraparesis, deafness, cortical blindness, occasionally loss of consciousness, and transient global amnesia. Sources of emboli should be sought. Risk factors are the same as for stroke and should be identified and managed appropriately.

Differential Diagnosis of TIA

This includes all conditions that may cause transient neurologic symptoms.

- Epilepsy: usually distinguished by features such as jerking

- Migraine: usually associated with headache, which is rare in TIAs

- Hypoglycemia

- Multiple sclerosis (MS)

- Intracranial lesions

Investigation and Diagnosis of TIA

These should identify risk factors, find the cause of the TIA, and exclude other causes of symptoms, as for stroke. Carotid Doppler studies or angiography may identify stenoses.

Treatment

Risk factors should be controlled, particularly hypertension. Cholesterol should be lowered to reduce coronary risk. Aspirin 75-300 mg daily reduces the risk of subsequent nonfatal stroke, myocardial infarction, and vascular deaths. More recent evidence suggests that dipyridamole MR, 200 mg daily, has a protective effect for subsequent neurologic events, which are additional to the protective effect of aspirin.

Anticoagulation should be considered if TIAs continue despite antiplatelet treatment, or if there is a known cardiac source of embolism. Carotid endarterectomy is indicated for recurrent TIAs in the appropriate distribution if the responsible carotid stenosis is over 70% of the luminal diameter.

Prognosis

Patients with TIAs in the carotid distribution fare worse than those with TIAs in the vertebrobasilar territory. The risks of stroke and myocardial infarction are significantly increased, at about 5% per year each.