Table of Contents

The definition of status epilepticus has evolved as understanding of its potential sequelae has increased. Before examining the different causes of generalized convulsive status epilepticus (GCSE), it is important to first discuss this changing definition.

Previously defined as any seizure activity lasting for more than 30 minutes, most neurologic organizations and trials are now defining GCSE as two seizures or more without return to neurologic baseline OR any seizure lasting more than 5 minutes. This updated definition reflects a new recognition of the increased morbidity and mortality associated with prolonged seizure activity. Some studies have shown a 30- day mortality in adults with GCSE of 19% to 27%.

Importantly, mortality has been shown to correlate directly with the duration of the seizure. These facts underscore the importance of rapidly identifying the underlying etiology of GCSE.

While nonadherence with medications in patients with known seizures remains the most likely underlying cause of GCSE, up to 50% of GCSE patients have no prior seizure history. This means that other causes of GCSE must be considered up front when we are dealing with seizures that are refractory to standard treatment.

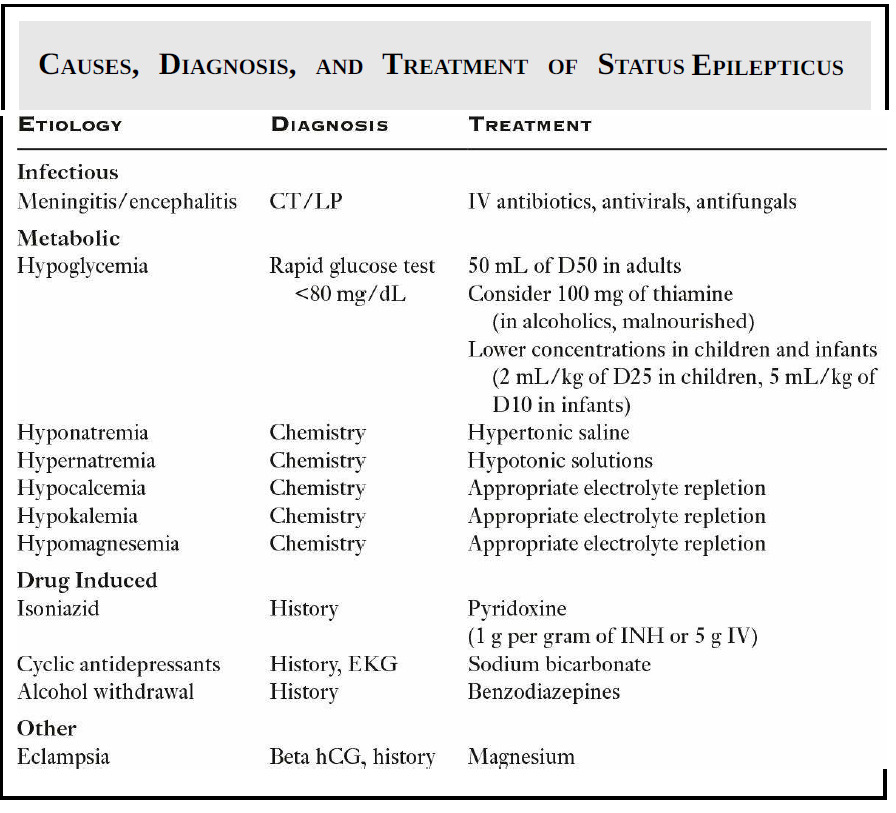

The easiest way to approach these atypical causes of GCSE is to break them down into broad categories:

- Infectious

- Metabolic

- Drug related

- Other.

Infectious etiologies

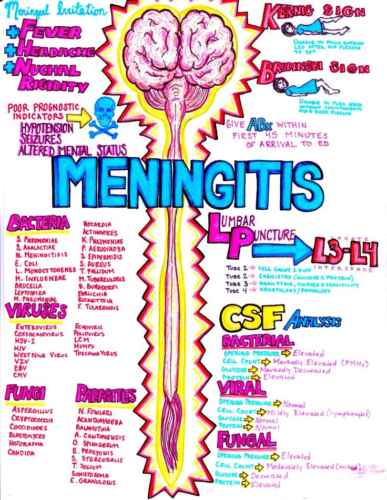

- Infectious etiologies such as meningitis and encephalitis can both cause GCSE.

- Fever and infection have been cited as the most common cause of seizures in children.

- Computed tomography (CT) of the head and lumbar puncture (once the patient has stopped seizing!) may be necessary to rule out CNS infection, especially in the setting of undifferentiated fever in an adult.

Metabolic disturbances

- Metabolic disturbances are frequently responsible for GCSE.

- Hypoglycemia is one of the most common and readily diagnosed etiologies. Seizure activity can occur when blood glucose is below 45 mg/dL. A rapid bedside glucose test should be done as soon as possible.

- Both hyponatremia and hypernatremia are also common metabolic derangements that can lead to GCSE. A sodium level <120 mEq/L or >160 mEq/L should alert us to the diagnosis.

- Hypocalcemia, hypokalemia, and hypomagnesemia often occur concurrently and should be treated simultaneously.

Drugs

- A multitude of drugs can cause GCSE and the list is too extensive to be completely addressed here.

- Major culprits that should not be overlooked include

- Isoniazid (INH)

- Antidepressants (particularly tricyclic antidepressants, which are making a comeback)

- Lithium.

- Methamphetamine intoxication and alcohol withdrawal are also on the differential.

Other Causes

- Lastly, there are many “other” causes of GCSE.

- In the young (possibly pregnant) woman with seizure, eclampsia should be considered, even in the postpartum period, as a significant number of cases occur in the weeks after delivery.

- In addition, trauma, stroke, neoplasm, and degenerative CNS diseases round out our list of “other” causes to consider

When faced with GCSE, we need to think broadly and consider the wide range of possible etiologies beyond mere medication nonadherence. Many of these etiologies are rapidly reversible with treatments that can terminate further seizure activity and directly reduce morbidity and mortality.

Key Points

- GCSE is a serious disease process and should be terminated as soon as possible.

- Hypoglycemia is the most common metabolic cause of GCSE, followed by sodium imbalances.

- Don’t forget about eclampsia in the young seizing female patient, even in the postpartum period.

- Keep an open mind when presented with GCSE. Infectious, metabolic, drug-induced, and “other” atypical causes must be considered in the differential.