Table of Contents

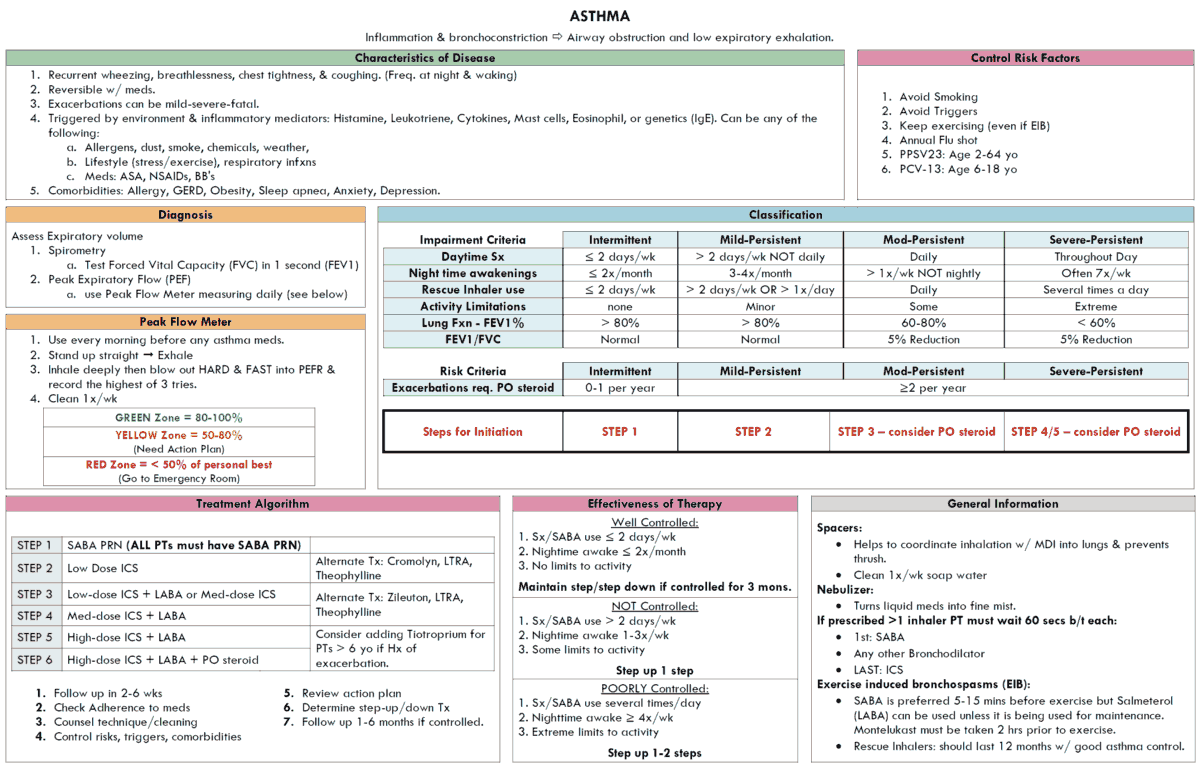

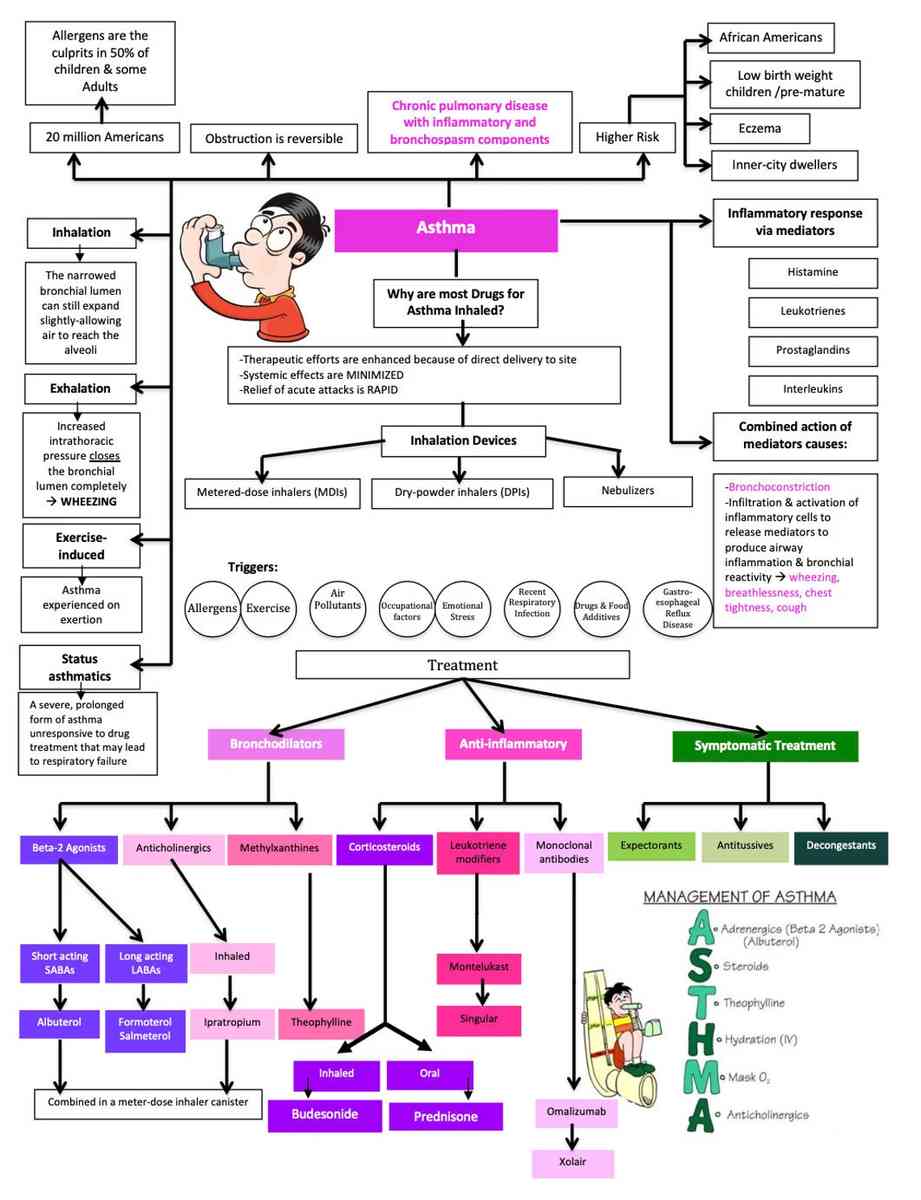

Asthma is a disease of the airways characterized by an increased responsiveness of the tracheobronchial tree to many different stimuli. It is manifested by paroxysms of shortness of breath, cough, and wheezing. These symptoms may resolve spontaneously or be relieved by treatment.

Asthma is episodic with acute exacerbations interspersed by symptom-free periods. Typically, most attacks are short (minutes to hours), and clinically the patient appears to recover completely after an attack. In more severe asthma, patients can experience some degree of airway obstruction daily with accompanying symptoms.

Incidence

Asthma is very common and occurs in about 5% of the population in most Western countries. Bronchial asthma occurs at all ages but peaks in childhood and is more common in boys. However, in adult asthma, the sex ratio is about equal by the age of 30 years.

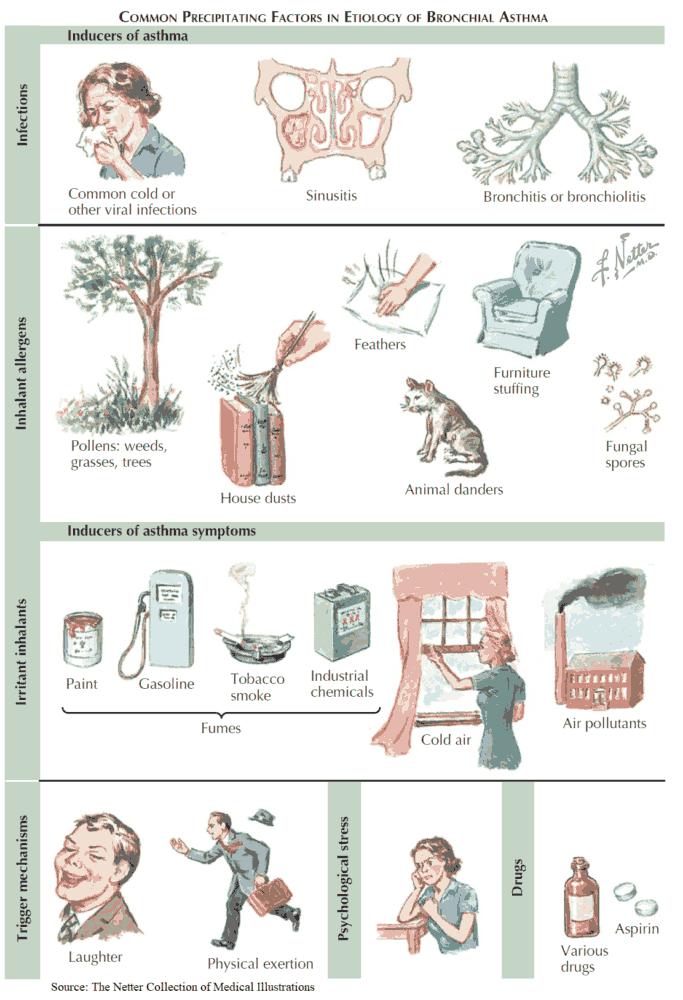

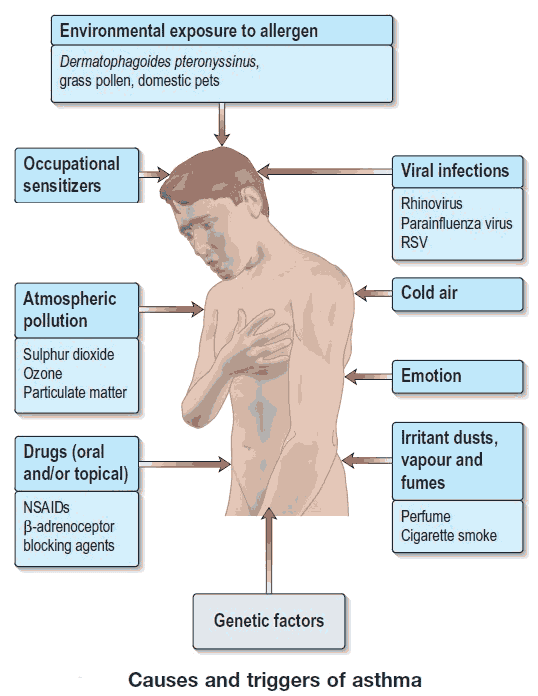

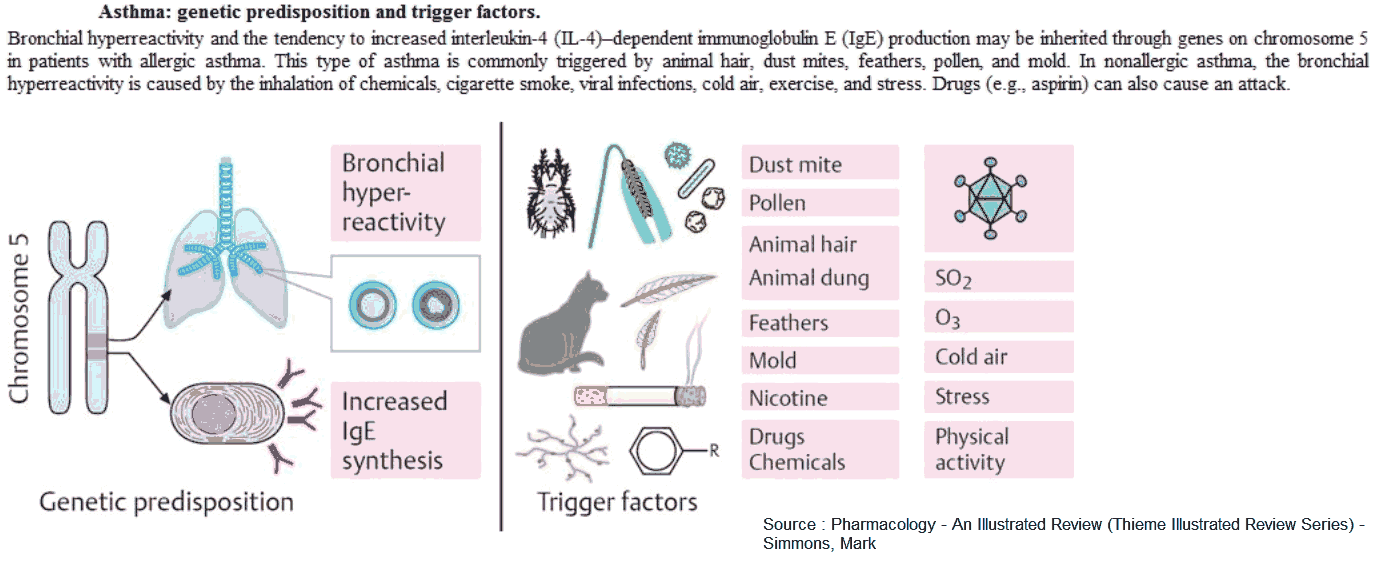

Etiology of Asthma

It is helpful to classify asthma by the main factors associated with acute episodes, i.e., into allergic asthma and intrinsic asthma.

Allergic asthma is often associated with a personal or family history of allergy such as hay fever, urticaria, and eczema. There may also be increased levels of immunoglobulin (Ig) E in the serum and a positive response to provocation tests (e.g., methacholine challenge).

Intrinsic (or idiosyncratic) asthma is a term used to define those patients presenting with no personal or family history of allergy, with negative skin tests, and with normal serum levels of IgE. Many develop typical symptoms following an upper respiratory infection, which, after several days, leads to paroxysms of wheezing and shortness of breath that can last for months.

In general, asthma that occurs in childhood or early adult life tends to have a strong allergic component, whereas asthma that develops late tends to be nonallergic. Despite this, many patients do not fit into either category but fall into a group with a mixture of allergic and nonallergic features.

Pathophysiology of Asthma

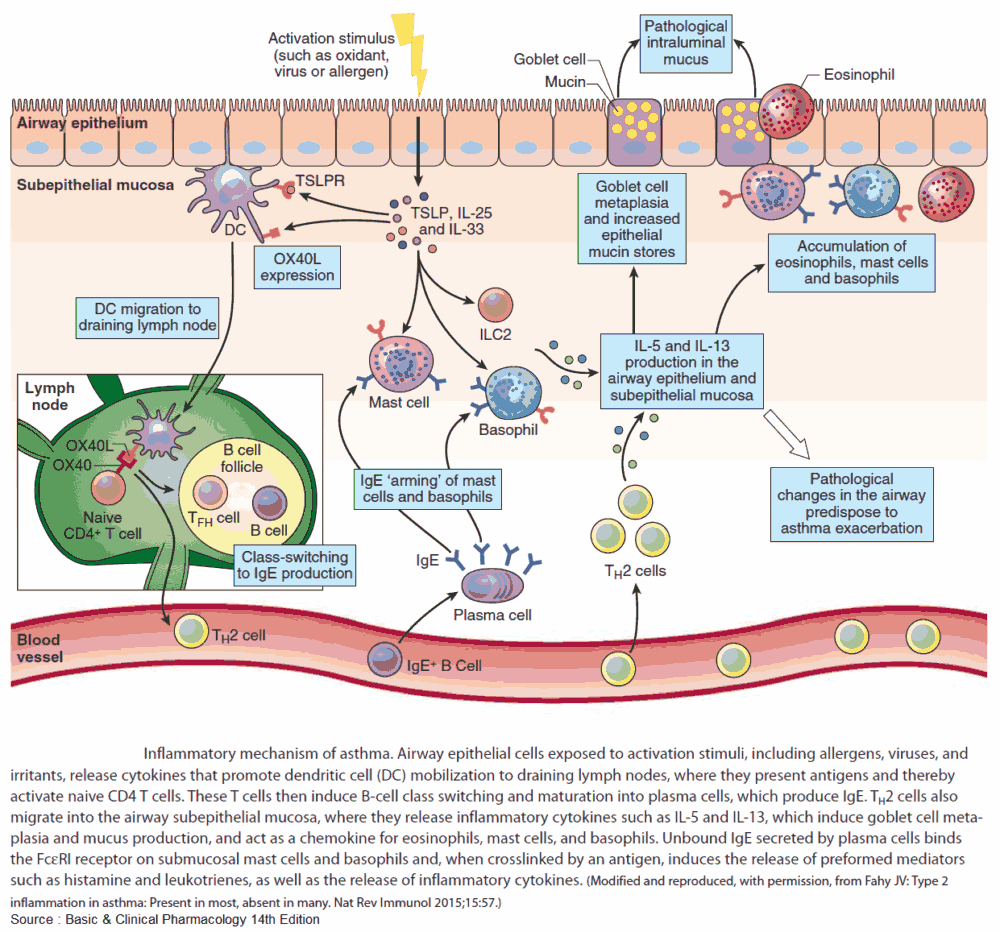

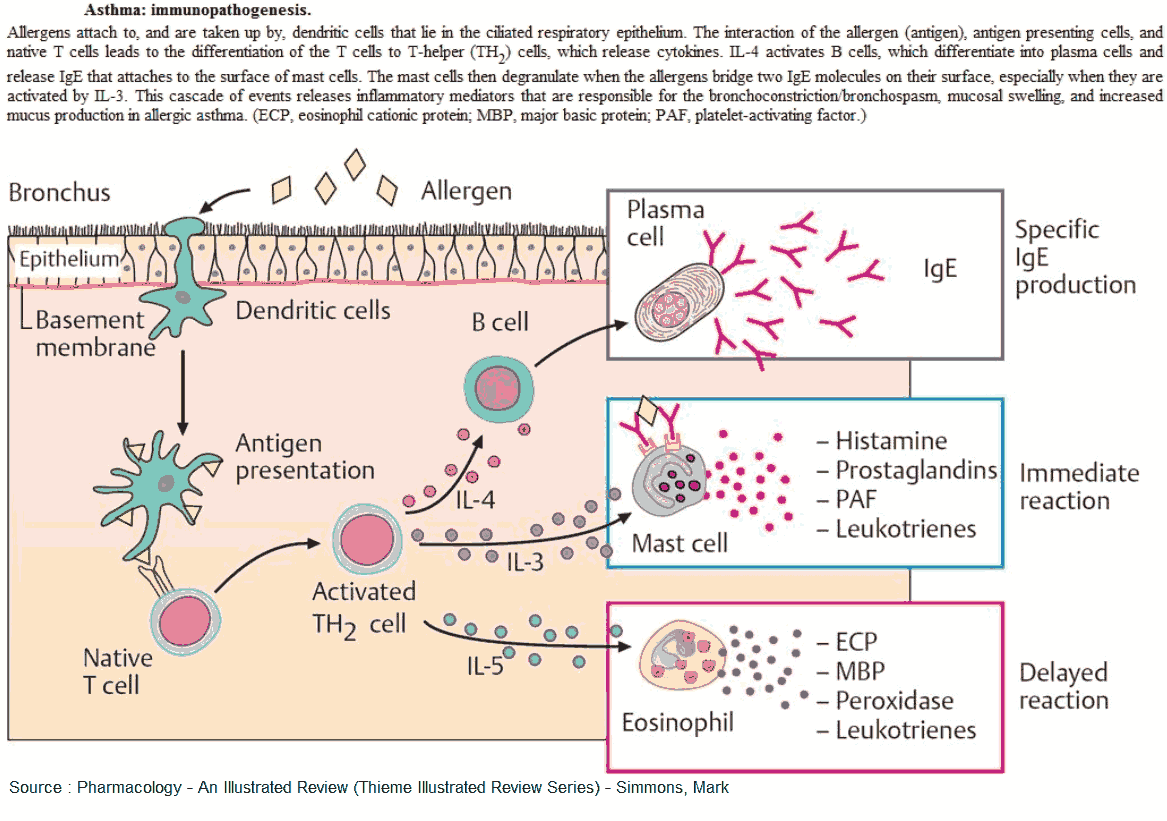

Many theories have been proposed to explain the increased airway reactivity of asthma, but the basic mechanism remains unknown. The most popular hypothesis is that of airway inflammation.

This is based on the observation that increased numbers of mast cells, epithelial cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes have been found in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with asthma.

Along with these cellular components of inflammation a variety of inflammatory mediators such as histamine, bradykinin, the leukotrienes C, D, and E, and platelet-activating factor; prostaglandins E2 and F2α have also been found.

The clinical features of asthma probably derive from an interaction between the normally resident and infiltrating inflammatory cells in the airways and the surface epithelium. These produce an intense immediate inflammatory reaction involving bronchoconstriction, vascular congestion, and edema formation-the pathologic hallmarks of asthma.

Leukotrienes, in addition to evoking contraction of airway smooth muscle and mucosal edema, may also account for other typical features of asthma, such as increased mucus production and impaired mucociliary transport.

A number of factors interact with normal airway responsiveness and provoke acute episodes and include the following:

- Allergens (e.g., house dust, mites, and animal dander).

- Drugs (e.g., β-blockers).

- The environment (e.g., climatic conditions, cold air, and air pollution).

- Occupations (e.g., exposure to industrial chemicals, drugs, metals, dusts).

- Infections (e.g., viral and bacterial).

- Exercise.

- Emotion.

Clinical Features of Asthma

The symptoms of asthma consist of a triad of:

- shortness of breath

- cough

- wheezing

In its most typical form, asthma is an episodic disease, and all three symptoms coexist. At the onset of an attack, patients experience a sense of constriction in the chest, often with a nonproductive cough.

Respiration becomes audibly harsh, wheezing in both phases of respiration becomes prominent, expiration becomes prolonged, and patients frequently have both tachypnea and tachycardia.

If the attack is severe or prolonged, there may be a loss of breath sounds, and wheezing becomes either very high-pitched or inaudible. Accessory muscles of respiration can be seen, and pulsus paradoxus often develops.

Less typically, a patient with asthma may present with intermittent episodes of nonproductive cough or shortness of breath on exertion. These patients often have a normal physical examination but may wheeze after repeated forced exhalations or may show evidence of airways obstruction with spirometry. Occasionally a provocation test may be required to make the diagnosis of airway hyperresponsiveness.

Confirming the Diagnosis of Asthma

Diagnosing asthma is usually not difficult, especially if the patient is seen during an acute attack. In addition, the history of episodic symptoms and a history of eczema, hay fever, or urticaria is valuable. Nocturnal symptoms (e.g., awakening short of breath or wheezing), are very common features.

Investigations

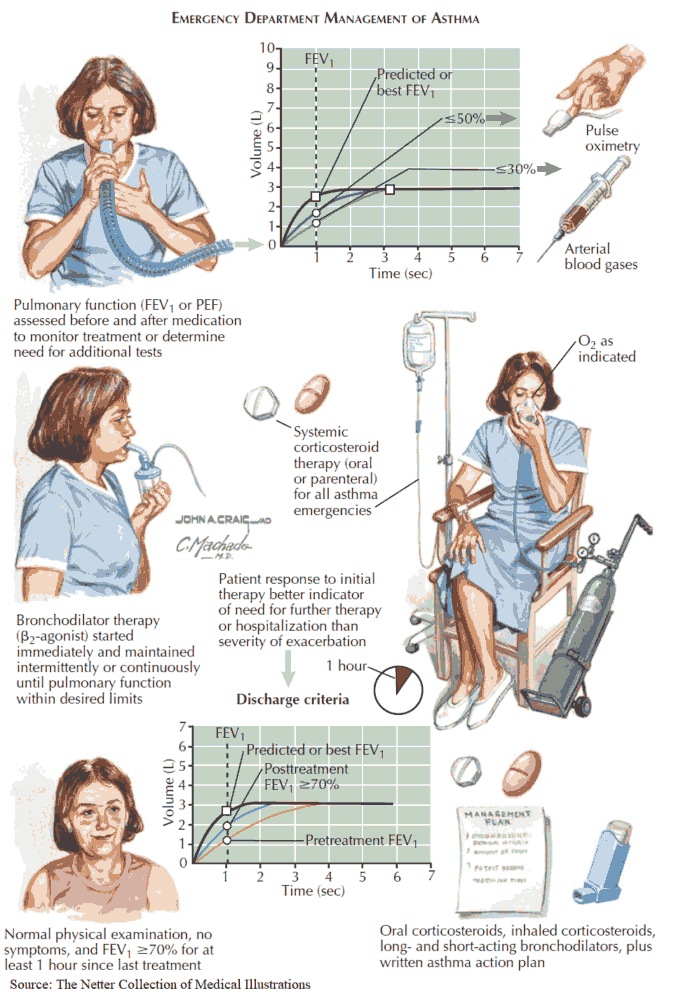

The diagnosis of asthma is established by demonstrating reversible airways obstruction. Reversibility is traditionally defined as a 15% or greater increase in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) following two puffs of a β2-agonist.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, peak expiratory flow rates (PEFRs) at home or the FEV1 in the clinic can be used to monitor the course of the illness and the effectiveness of therapy.

Sputum and blood eosinophilia and measurement of serum IgE levels may be helpful but are not specific for asthma. Similarly, a chest x-ray (CXR) showing hyperinflation is not diagnostic of asthma.

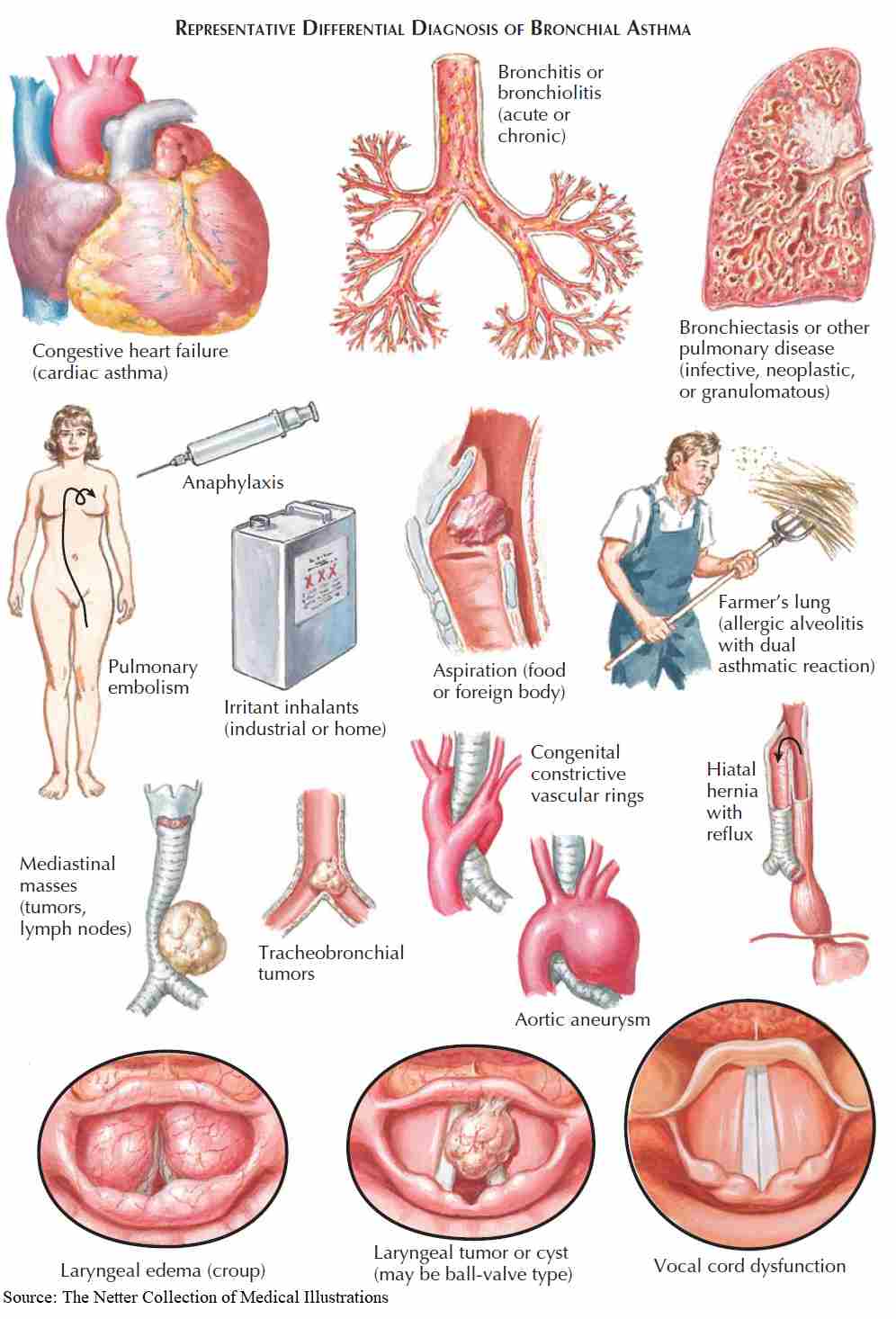

Differential Diagnosis

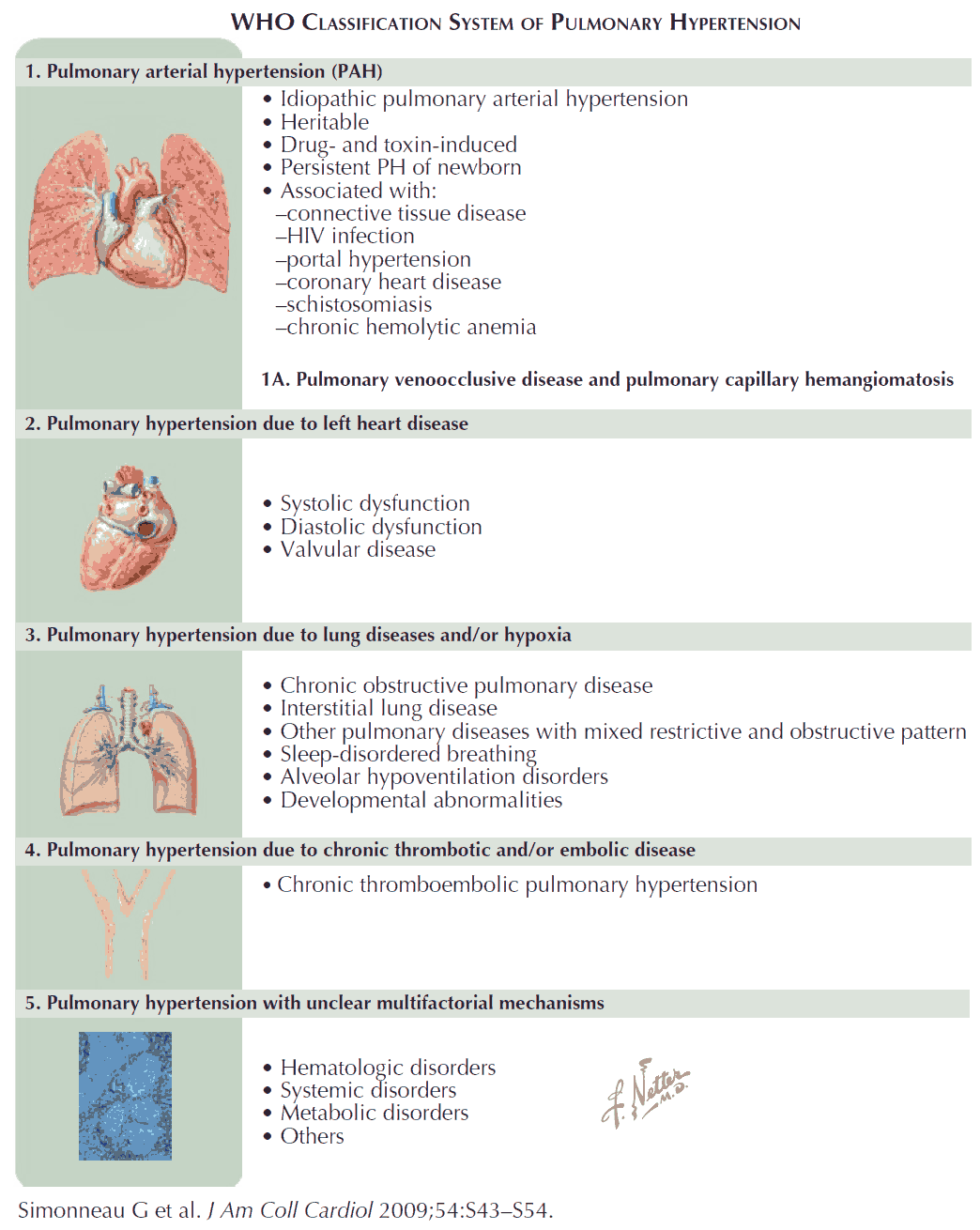

In a small minority of patients the diagnosis can cause some difficulty, and the following differential diagnoses for wheezing and shortness of breath should be considered:

- Upper airway obstruction: tumor, vocal cord paralysis, or laryngeal edema.

- Endobronchial disease (e.g., foreign body aspiration, neoplasm, bronchial stenosis).

- Left ventricular failure.

- Carcinoid tumors.

- Recurrent pulmonary emboli.

- Chronic bronchitis (COPD).

- Eosinophilic pneumonias.

- Systemic vasculitis with pulmonary involvement.

Management of Asthma

The elimination of the causative agent from the environment of an allergic asthmatic is the most successful means available for treating this condition.

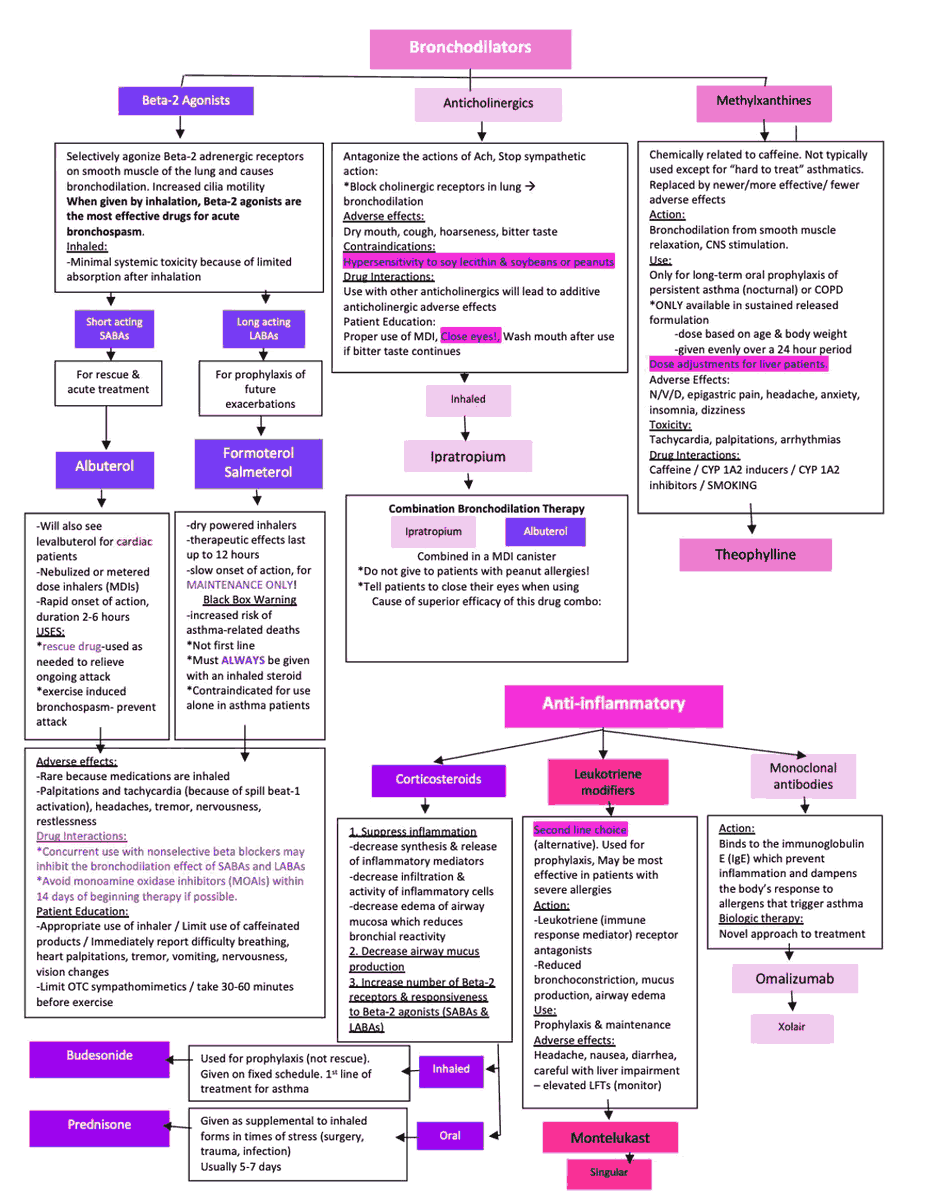

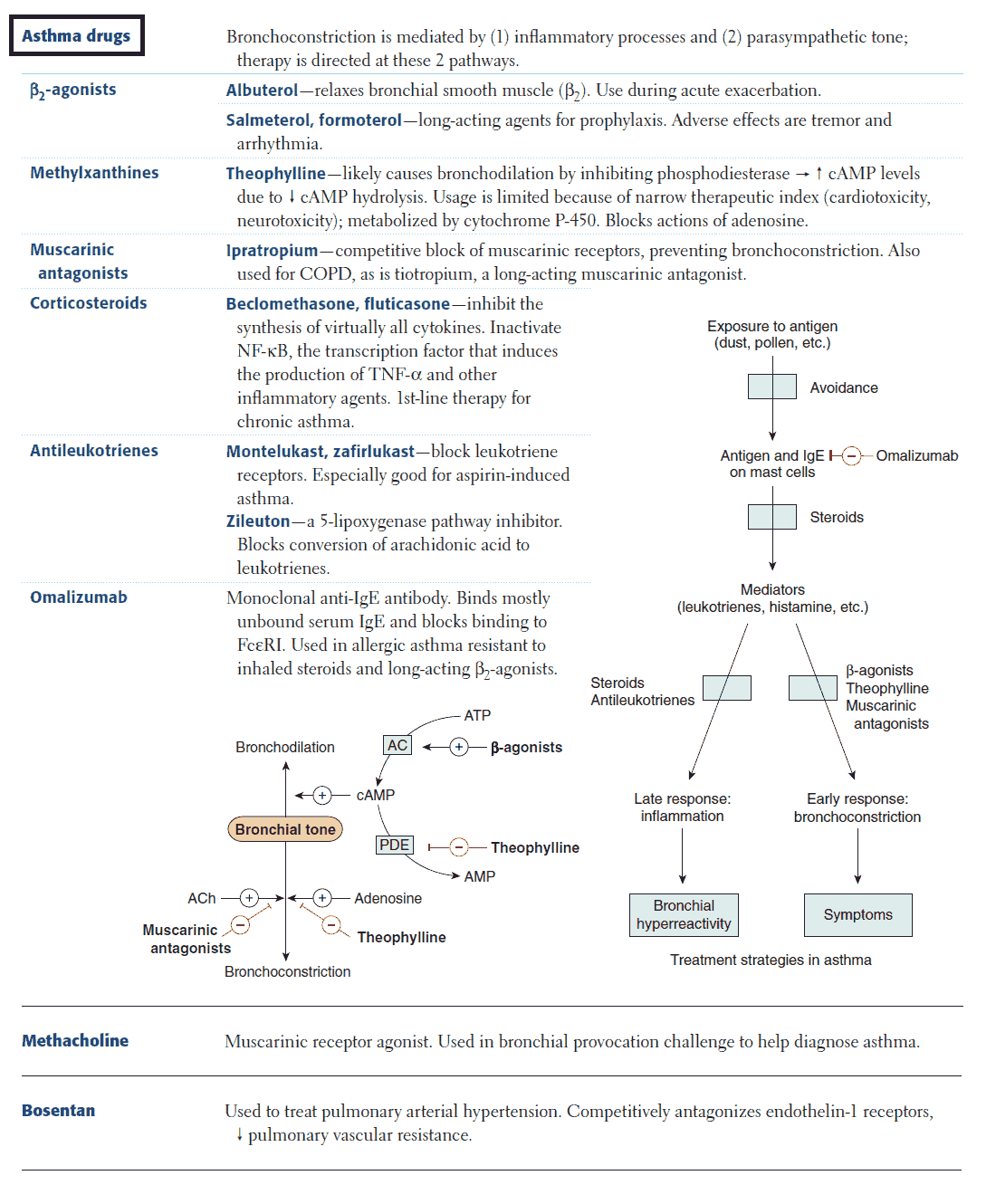

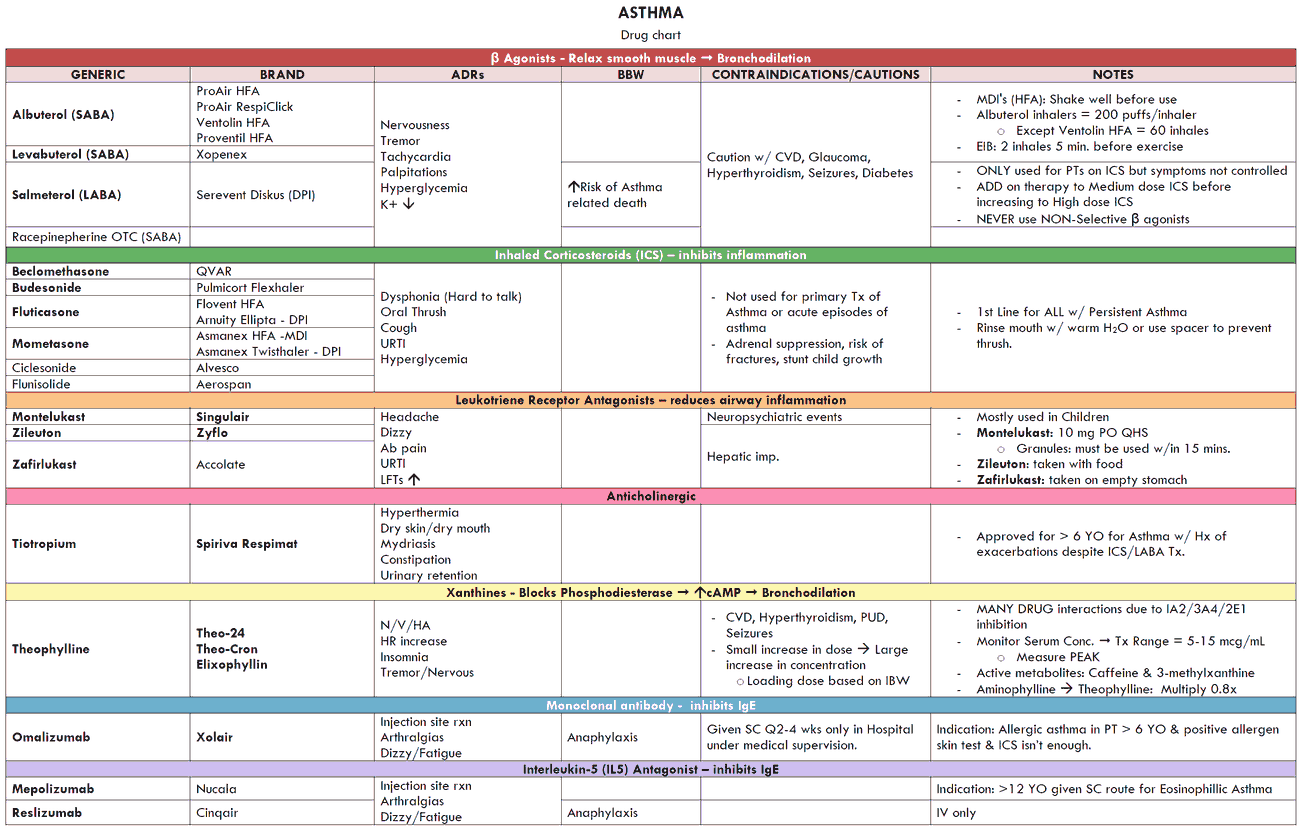

The treatments available for asthma can be divided into two general categories:

- Drugs that inhibit smooth muscle contraction (e.g., β2-agonists, methylxanthines or theophylline derivatives, anticholinergics).

- Drugs that prevent or reverse inflammation (e.g., corticoidsteroids, mast cell-stabilizing agents, and leukotriene antagonists).

In clinical practice the two most common settings in which patients require treatment are emergency treatment of acute severe asthma and chronic therapy.

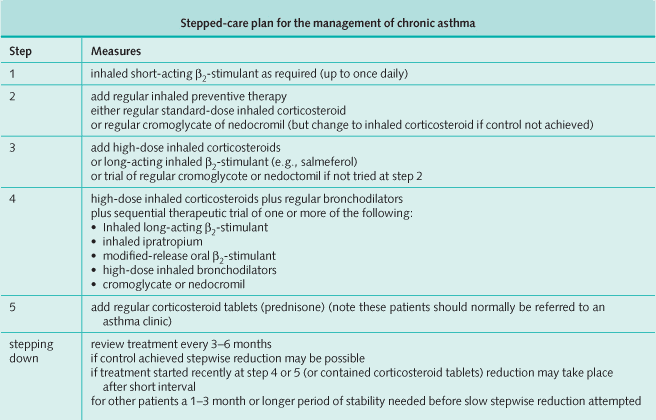

Chronic Therapy

Patients should be divided into categories depending on disease severity. Although firm distinctions do not exist among these groups, treatment guidelines are based on the severity of symptoms.

Mild

- Symptoms occur only with heavy exercise.

- 1 or 2 nocturnal awakenings per month.

- Lung function does not deteriorate over the course of the day.

Moderate

- Symptoms occur with mild exercise.

- 1 or 2 nocturnal awakenings per week.

- FEV1 = 60-70% of predicted with symptoms worse upon awakening.

Severe

- Symptoms occur with minimal exercise.

- Nocturnal symptoms more than twice per week.

- FEV1 < 60% of predicted.

Therapy is aimed at achieving a stable, asymptomatic state with the best pulmonary function possible. The first step is to educate patients to function as partners in their management. The severity of the illness needs to be assessed and monitored with objective measures of lung function.

Asthma triggers should be avoided or controlled, and plans should be made for both chronic management and treatment of exacerbations. Regular follow-up care is mandatory.

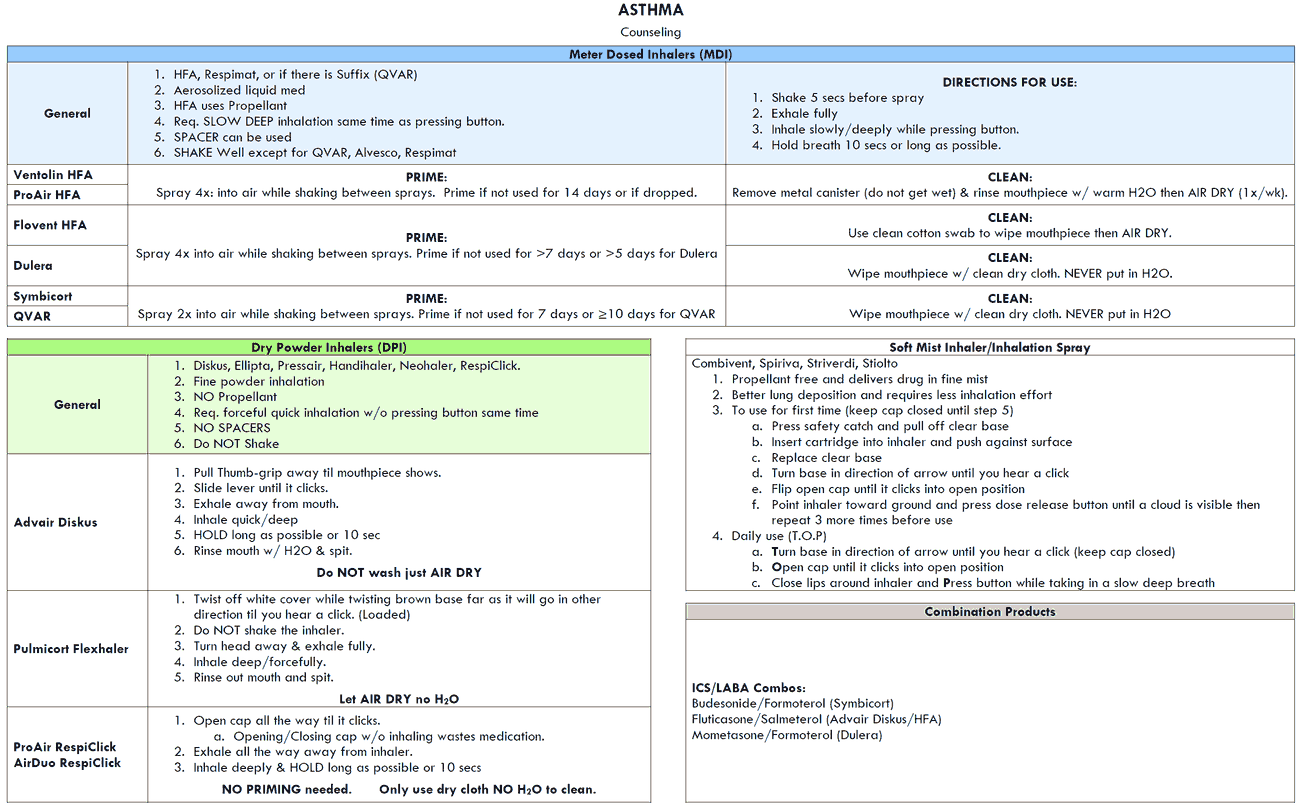

Drug therapy should be kept as simple as possible and infrequent symptoms require only the use of an inhaled β2-agonist on an as-needed basis. When features such as nocturnal awakenings and worsening daytime symptoms develop, inhaled steroids or mast cell-stabilizing inhalers should be added. If symptoms do not improve, the dose of inhaled steroids can be increased.

Severe asthma can be treated with long-acting inhaled β2 agonists, and antimuscarinic agents, (e.g., ipratropium). Note, however, that theophylline is not commonly used because of the need to check blood levels on a regular basis. Also note that ipratroprium is not used frequently for asthma but remains popular in the treatment of COPD.

Some patients with severe recurrent symptoms need oral steroids in a single daily dose. Once control is reached and sustained for several weeks, a step-down reduction in therapy should be undertaken, beginning with the most toxic drug, to find the minimal amount of treatment needed to keep the patient well. The PEFR should be monitored and treatment adjusted accordingly, particularly when corroborated by the patient’s symptoms.

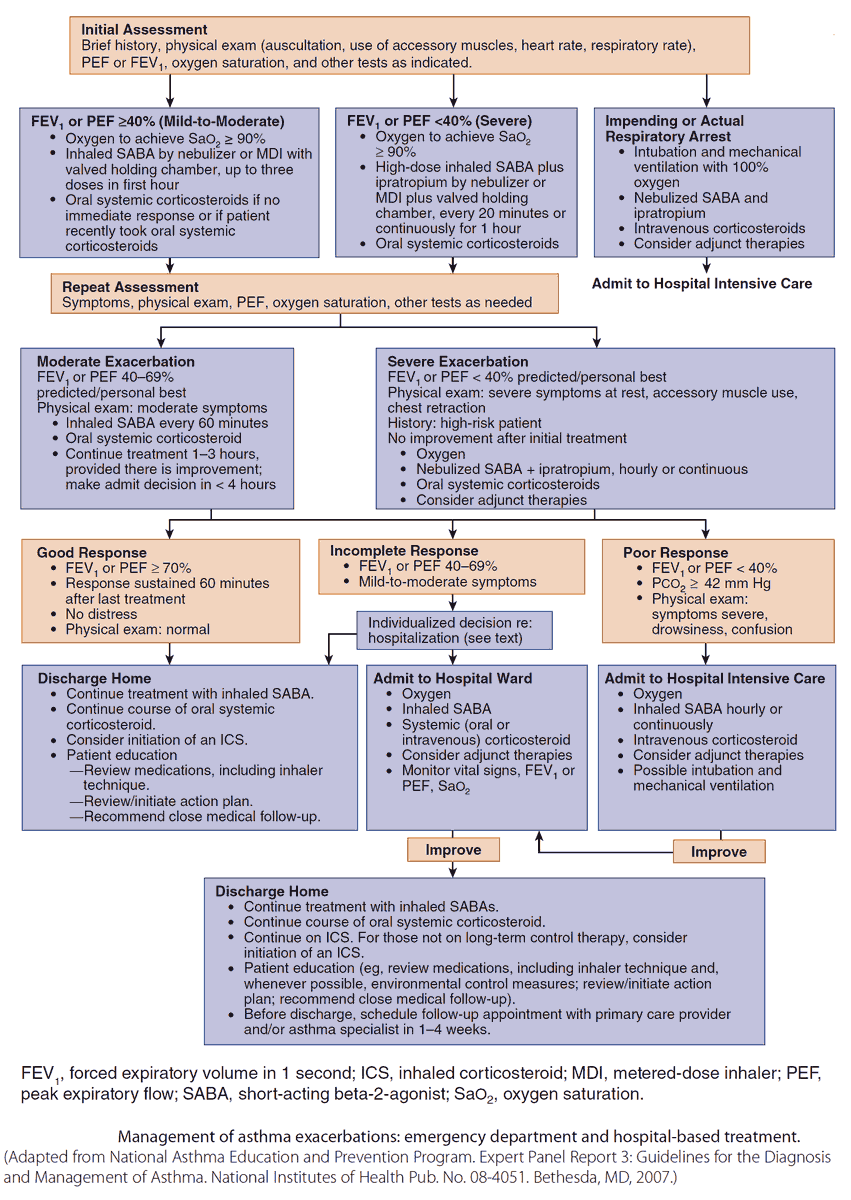

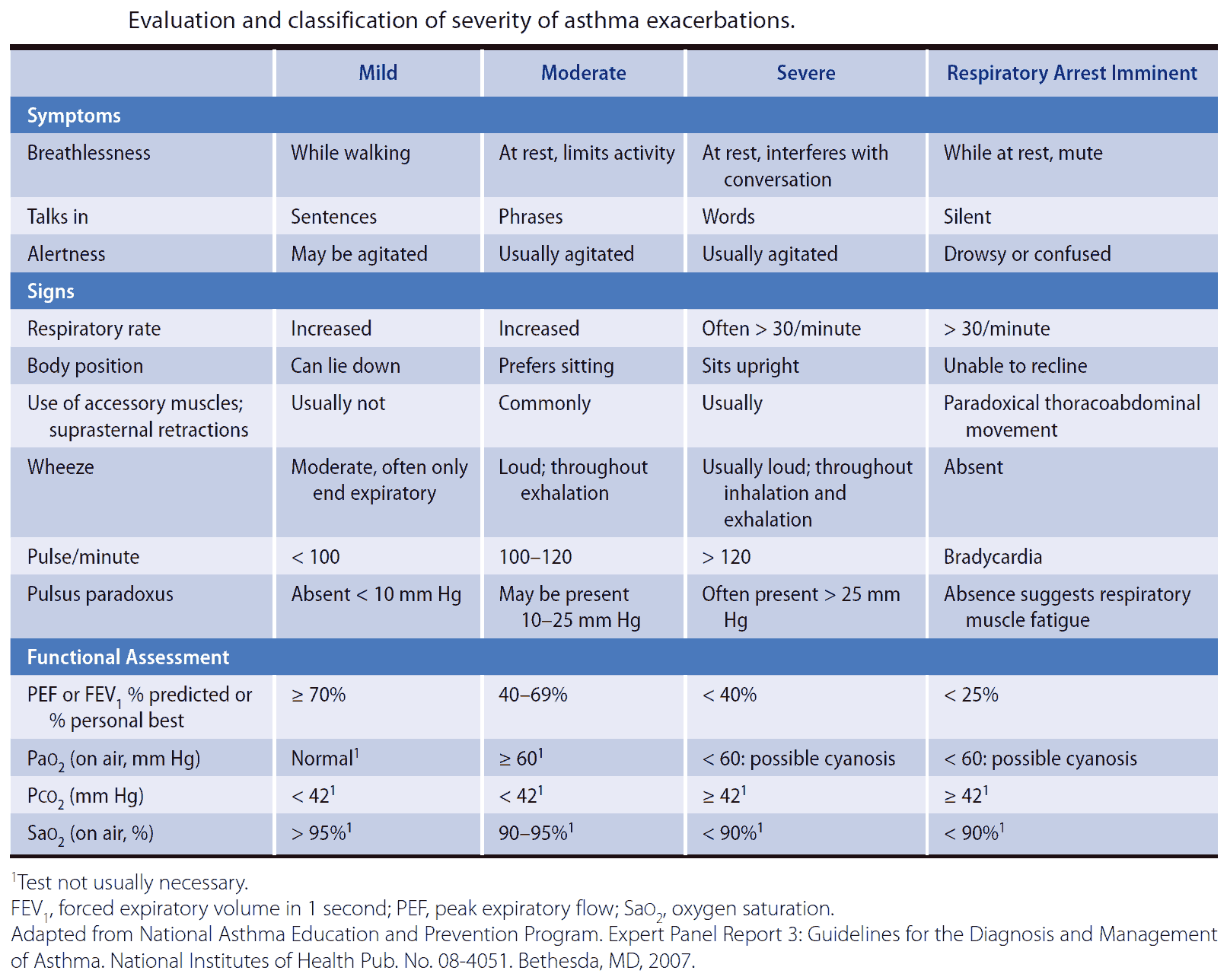

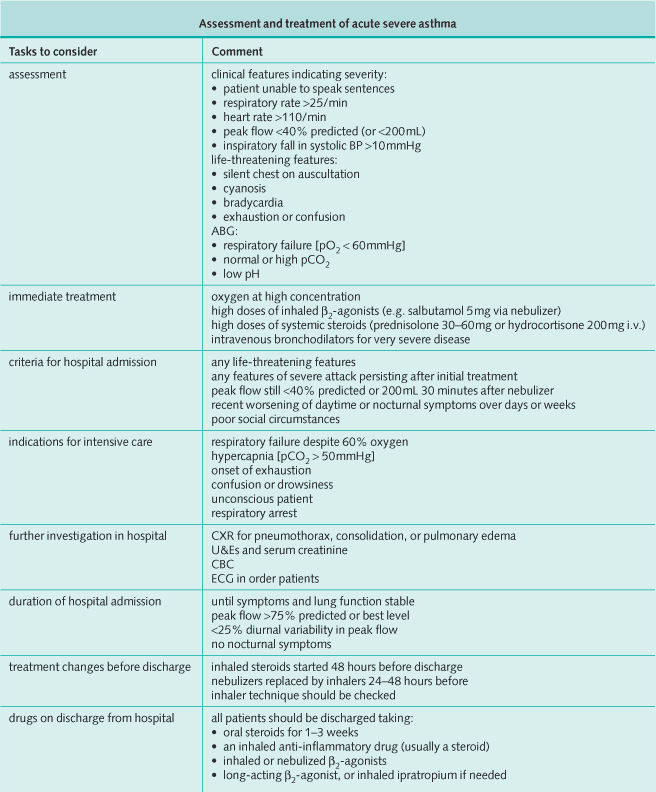

Emergency Treatment

Emergency treatment of acute asthma is one of the most common emergencies seen in ordinary medical practice, and its life-threatening nature can be underestimated by the less experienced.

Features indicating severe airway obstruction include

- presence of pulsus paradoxus

- use of accessory muscles

- marked hyperinflation of the thorax

- absent breath sounds.

Failure of these signs to remit promptly after aggressive therapy requires objective monitoring of the patient using measurements of arterial blood gases (ABGs) and the PEFR or FEV1.

Generally, there is a direct correlation between the severity of the obstruction with which the patient presents and the time it takes to resolve it.

When the PEFR falls by more than 20% of its previous value, if the magnitude of the pulsus paradoxus is increasing, and if serial measures of ABGs show that the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) is within the normal range or elevated, then the patient should be monitored in an intensive care setting and may need assisted ventilation.