Table of Contents

Definitions

Chronic bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis is a condition associated with excessive mucus production sufficient to cause cough with expectoration for at least 3 months of the year for more than 2 consecutive years.

Simple chronic bronchitis is characterized by mucoid sputum production, while chronic mucopurulent bronchitis is identified by persistent or recurrent purulent sputum in the absence of localized suppurative diseases such as bronchiectasis.

Emphysema

Emphysema is defined as the permanent, abnormal distention of the air spaces distal to the terminal bronchiole with destruction of alveolar septa.

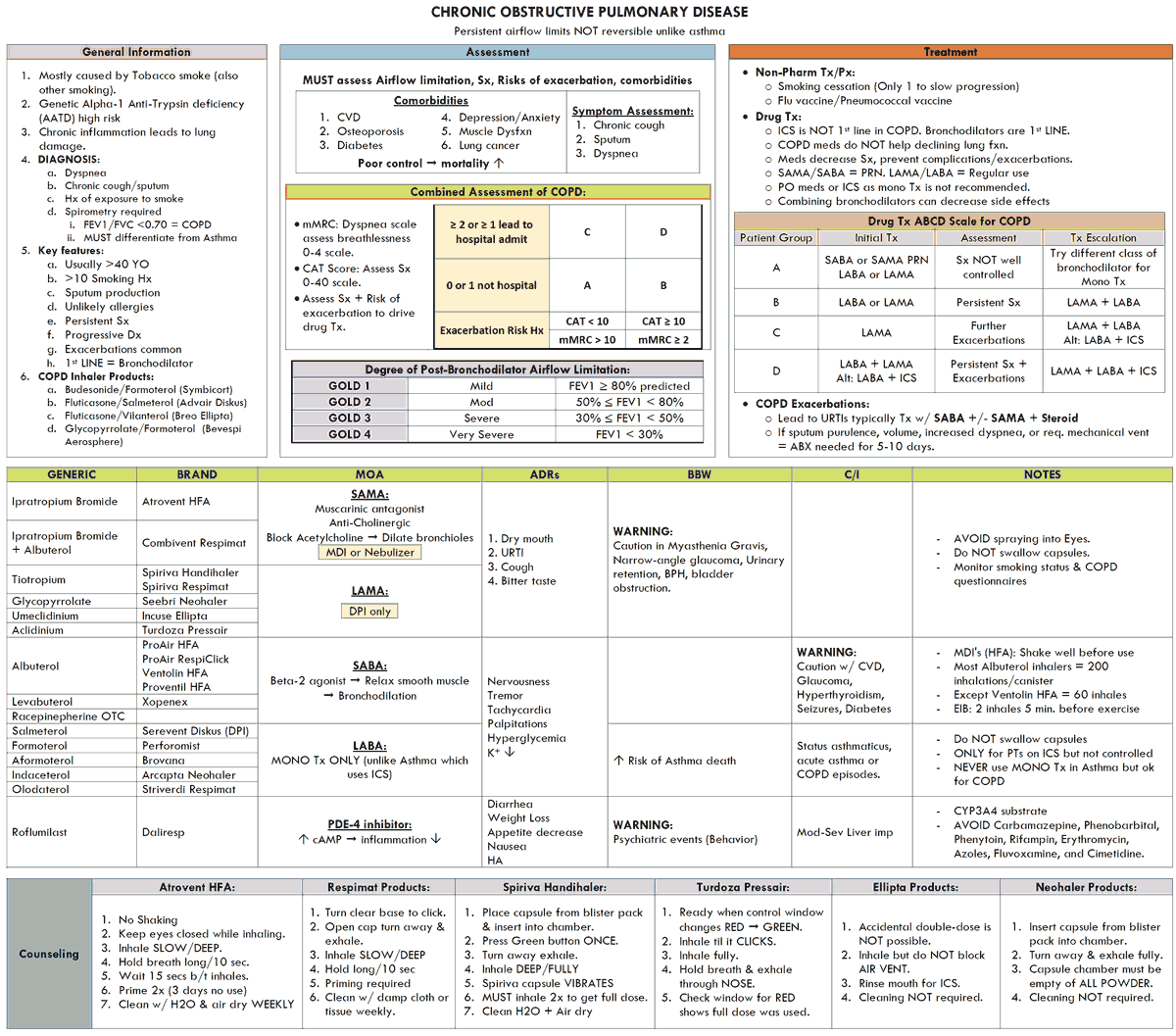

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined as a condition in which there is chronic obstruction to airflow due to chronic bronchitis with or without emphysema. Although the degree of obstruction may be less when the patient is free from respiratory infection and may improve somewhat with bronchodilators, significant obstruction is always present in these patients.

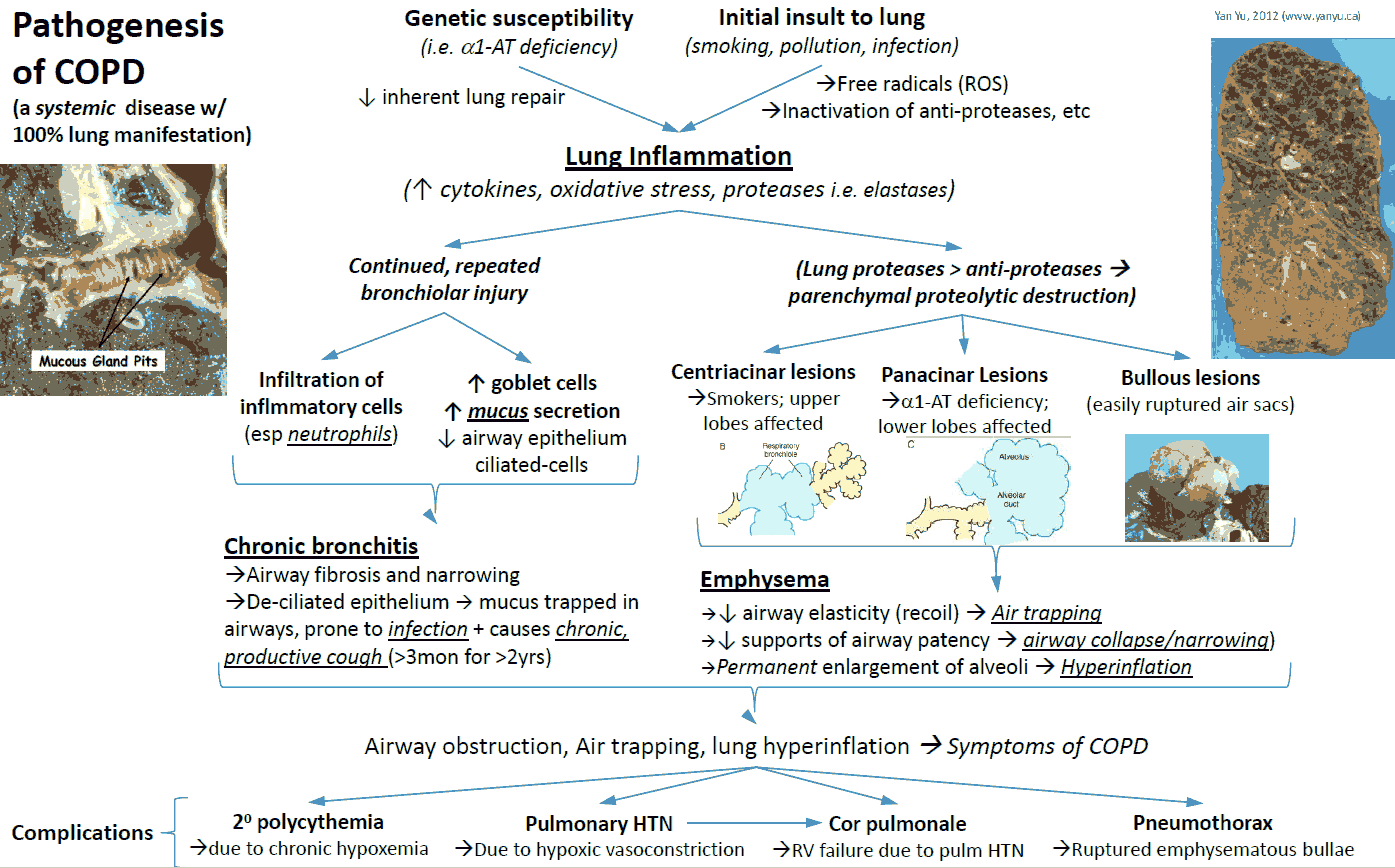

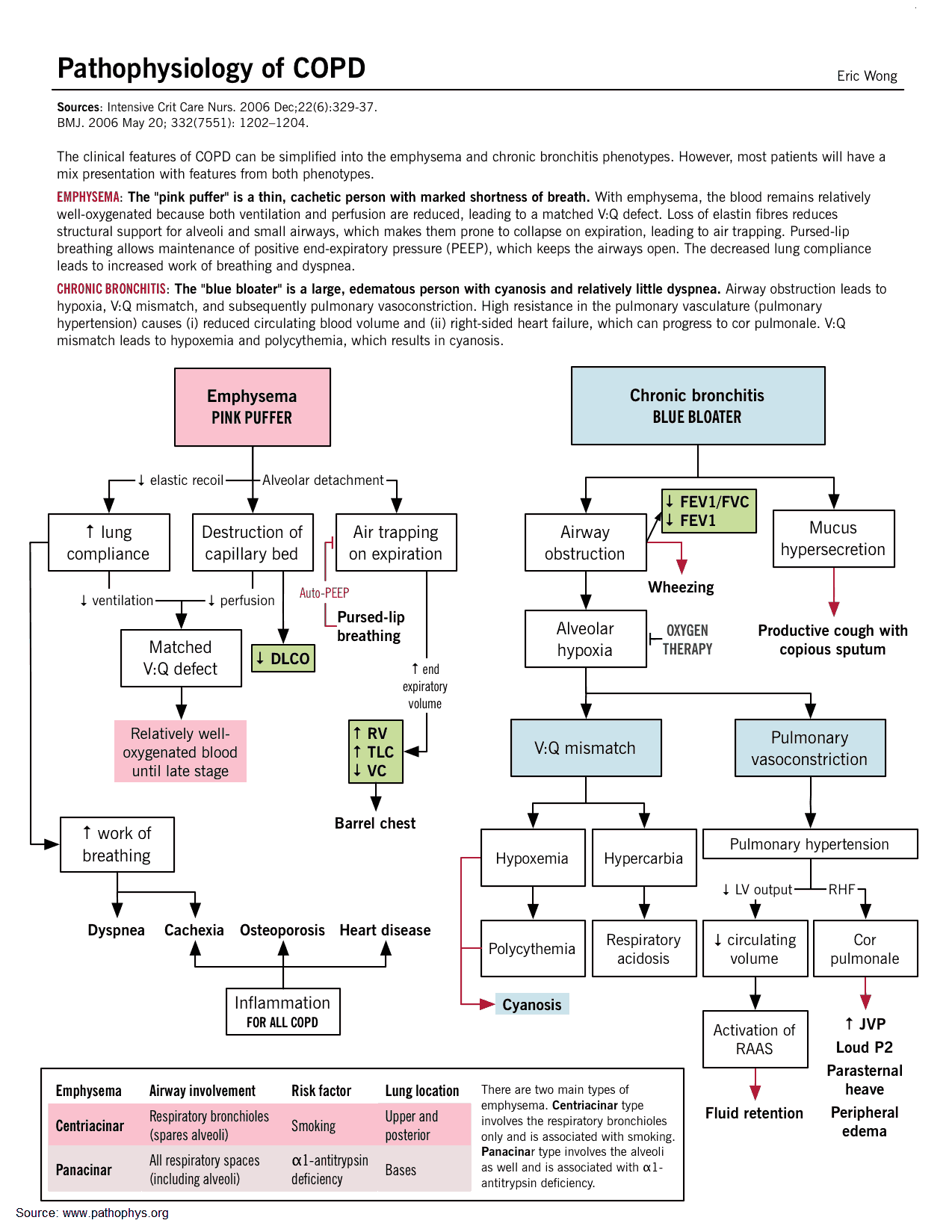

Pathophysiology of COPD

The hallmark of chronic bronchitis is hypertrophy of the mucus-producing glands found in the submucosa of large cartilaginous airways. Quantitation of this anatomic change is based on the ratio of the thickness of the submucosal glands to that of the bronchial wall.

In lungs from patients with COPD studied at post-mortem there is goblet cell hyperplasia, mucosal and submucosal inflammatory cells, edema, peribronchial fibrosis, intraluminal mucus plugs, and increased smooth muscle in small airways.

Inflammation in chronic bronchitis occurs at the alveolar epithelium and differs from the predominantly eosinophilic inflammation of asthma by the predominance of neutrophils and the peribronchiolar location of fibrotic changes.

Emphysema is classified according to the pattern of involvement of the gas-exchanging units (acini) of the lung distal to the terminal bronchiole.

With centriacinar emphysema, the distention and destruction are mainly limited to the respiratory bronchioles with relatively less change peripherally in the acinus. Because of the large functional reserve in the lung, many units must be involved in order for overall dysfunction to be detectable.

Panacinar emphysema involves both the central and peripheral portions of the acinus, which results, if the process is extensive, in a reduction of the alveolar-capillary gas exchange surface and loss of elastic recoil properties. When emphysema is severe, it may be difficult to distinguish between the two types because, most often, they coexist in the same lung.

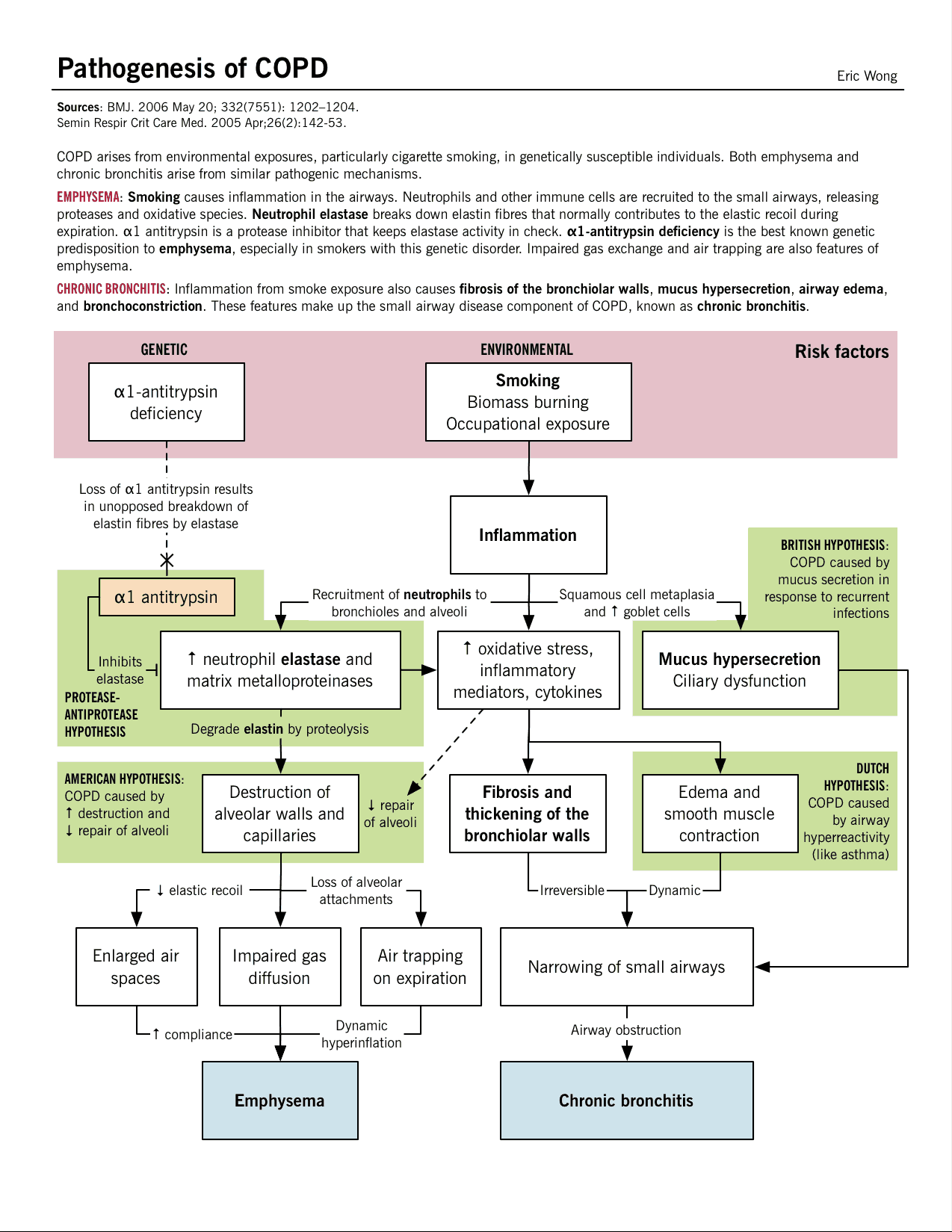

Etiology of COPD

Cigarette smoking

Cigarette smoking is the most commonly identified factor associated with both chronic bronchitis during life and extent of emphysema at post-mortem. Prolonged cigarette smoking impairs ciliary movement, inhibits function of alveolar macrophages, and leads to hypertrophy and hyperplasia of mucus-secreting glands. It is probable that smoke also inhibits antiproteases and causes polymorphonuclear leukocytes to release proteolytic enzymes acutely. Inhaled cigarette smoke can produce an acute increase in airways resistance due to vagally mediated, smooth-muscle constriction.

Air pollution

Air pollution with sulphur dioxide and particulate matter is associated with exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, and the incidence and mortality rates for chronic bronchitis and emphysema is probably higher in heavily industrialized urban areas.

Occupation

Occupations exposing workers to inorganic or organic dusts, or to noxious gases, result in a higher prevalence of chronic bronchitis among employees.

Acute respiratory infections

These have been implicated as one of the major factors associated with both the etiology and progression of COPD.

Familial and genetic factors

Familial aggregation of chronic bronchitis has been well demonstrated. α1-Antitrypsin (α1AT) deficiency is a recognized genetic cause of emphysema. Either decreased or absent serum levels of the protease inhibitor α1AT are found in some patients with early-onset emphysema.

Most members of the normal population have two M genes, designated as protease inhibitor type MM, but those with defective (Z and S) genes who are homozygous ZZ or SS have markedly decreased serum levels of α1AT and develop severe panacinar emphysema in their 20s and 30s.

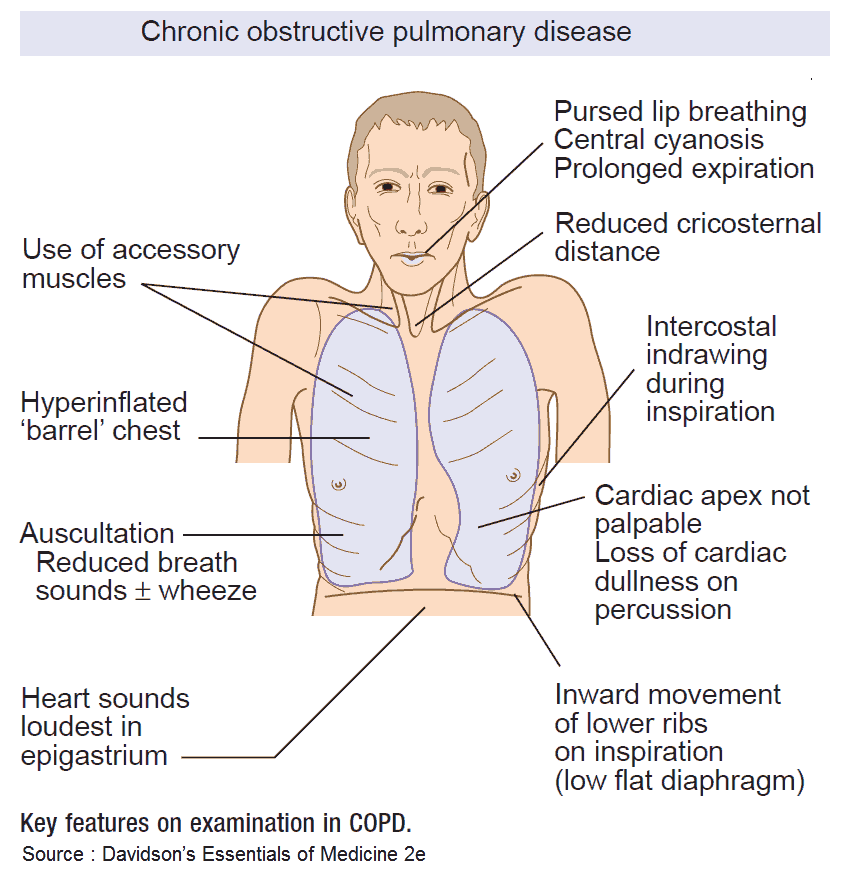

Clinical Features of COPD

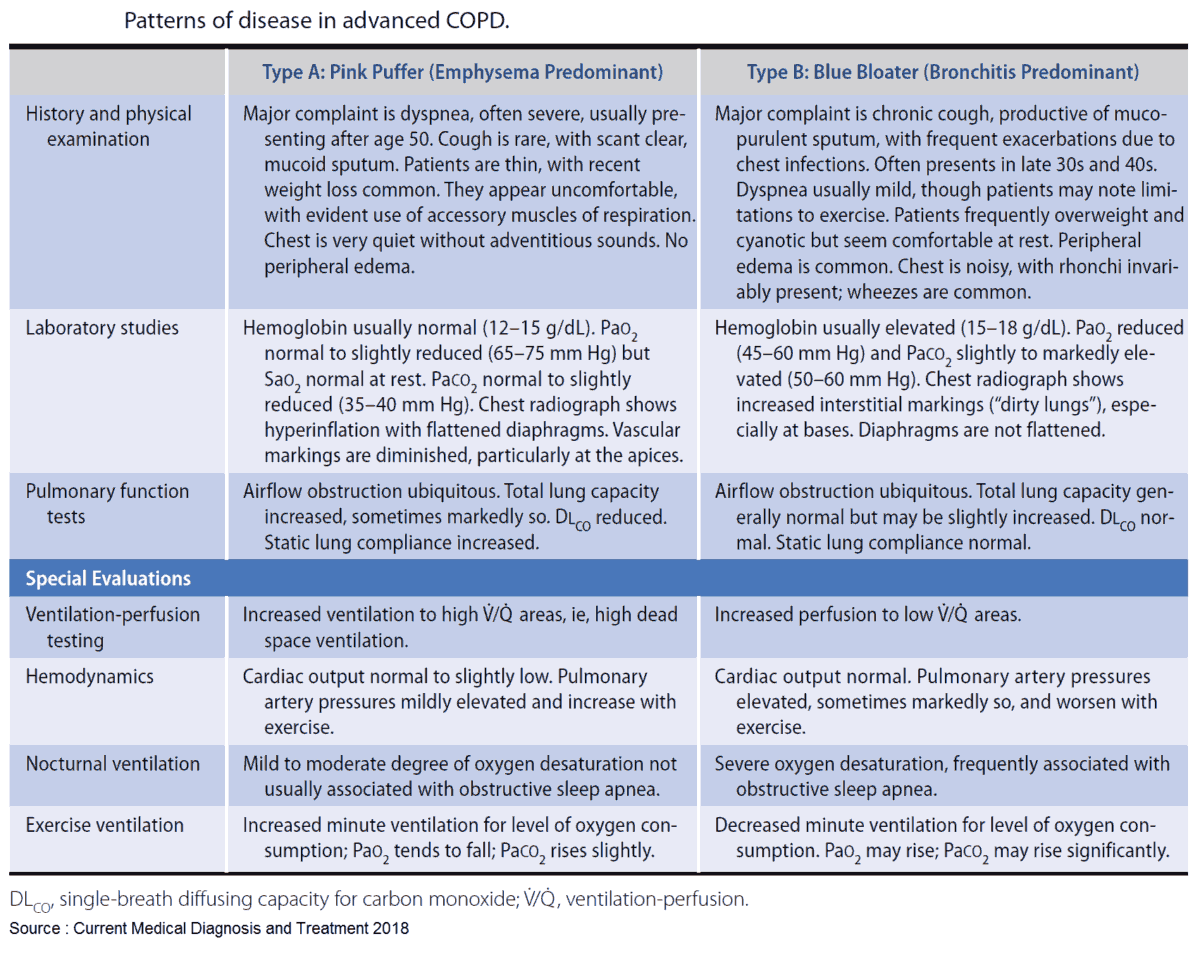

The clinical presentation of COPD varies in severity from simple chronic bronchitis without disability to patients with severe disability and chronic respiratory failure. In clinical practice it is common to encounter patients with fully developed COPD and, even though most patients will have features of both chronic bronchitis and emphysema, it is useful to categorize patients as having predominant features of one or other.

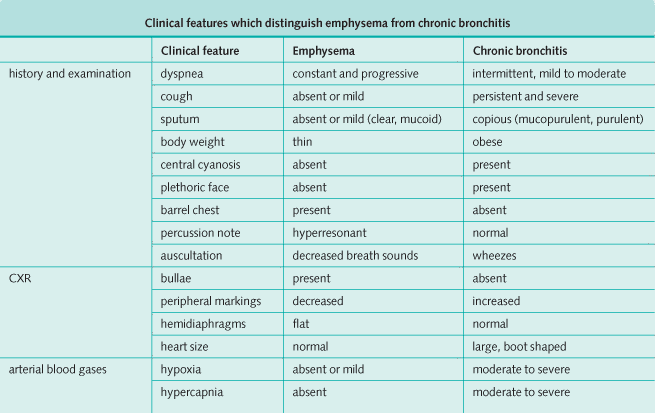

The clinical features of emphysema and chronic bronchitis are summarized in the tables below. It is important to remember, however, that most patients have a combination of features of both emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

Investigations

History, physical examination, and CXR should be supplemented by tests of lung function performed during a chronic stable period. Complete spirometry, lung volumes, transfer of carbon monoxide, and ABGs should be measured. Also, reversibility should be assessed by spirometry and lung volumes after the administration of bronchodilators.

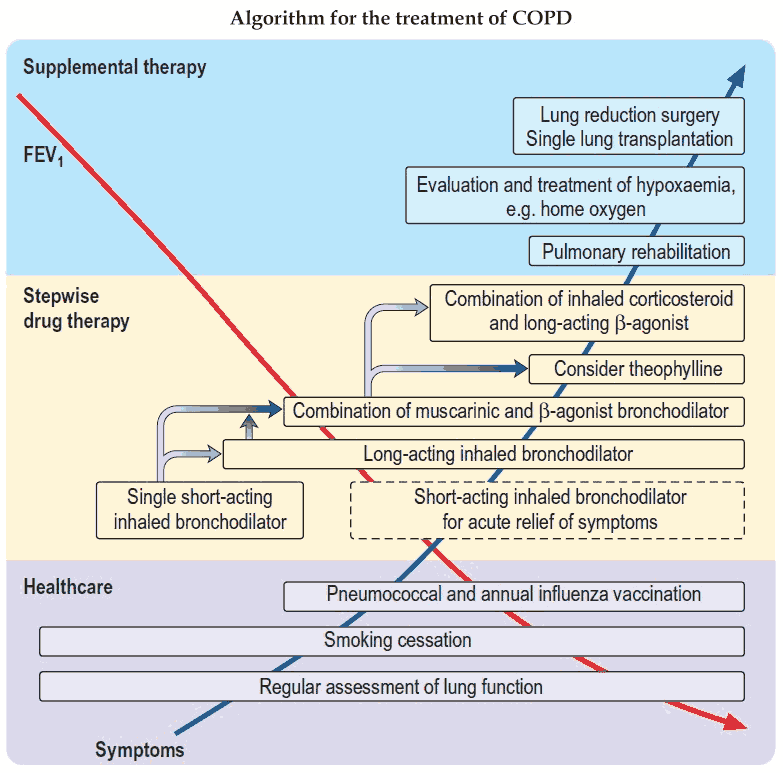

Management and Treatment of COPD

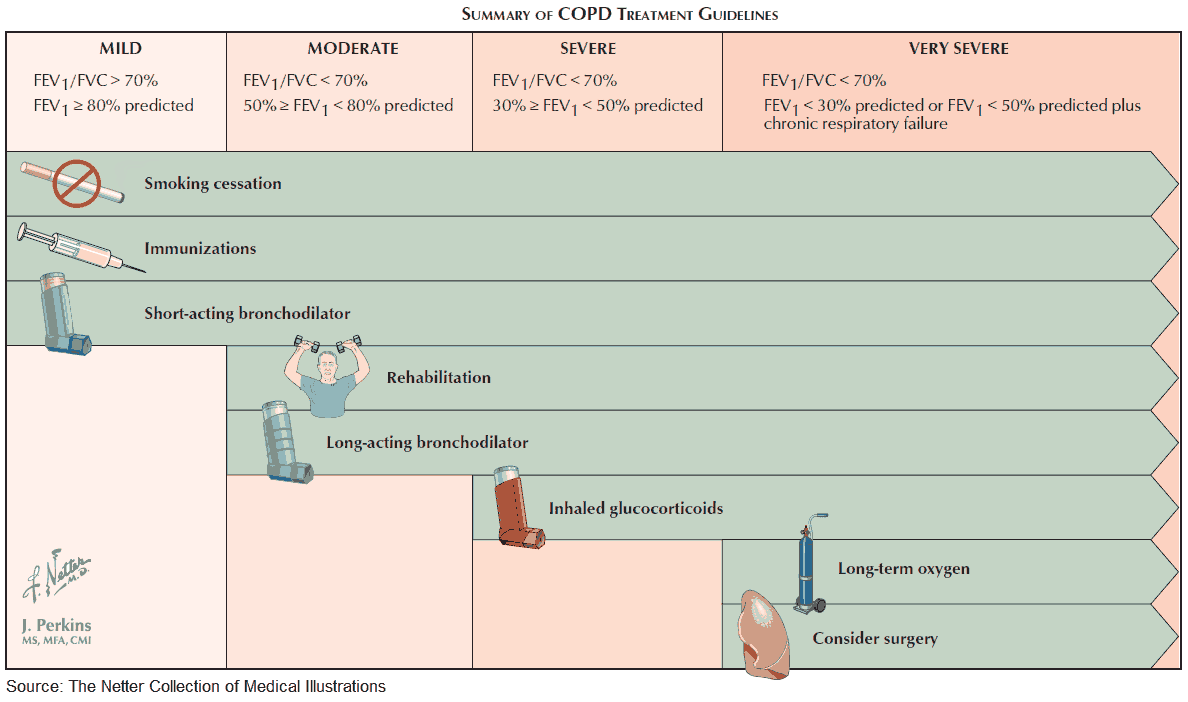

The management of patients with COPD is based on knowledge of the degree of obstruction, the extent of disability, and the reversibility of the patient’s illness. The extent of the airways obstruction and the potential to reverse this is key as there is a chance that treatment may be effective in improving the overall disability. Emphysema, however, is an irreversible process and so the prevention of its progression and the avoidance of acute infections are the main approach to management.

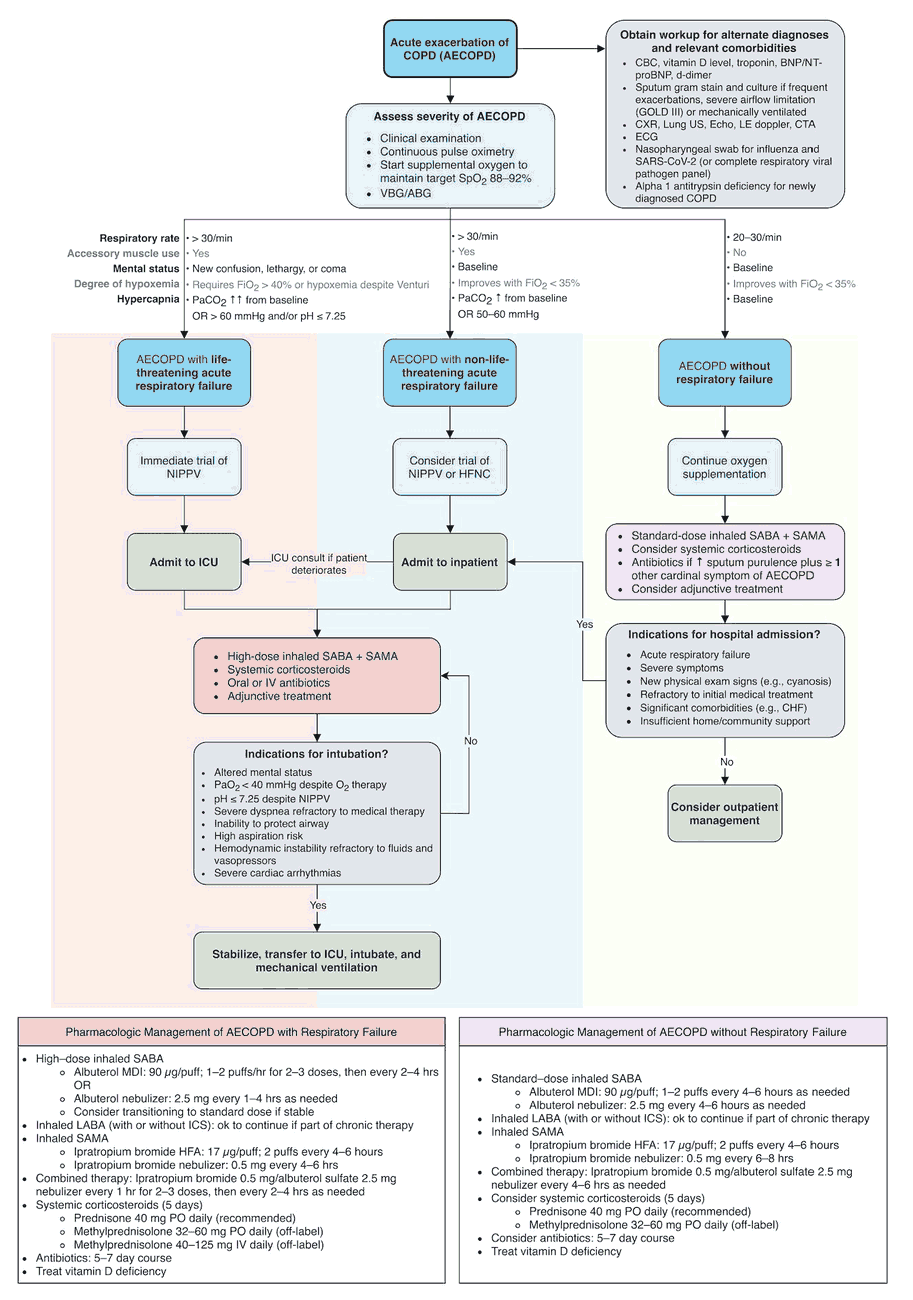

Treatment strategies for COPD are varied, and a multidisciplinary approach to the patient is often required. A treatment plan should consider the following:

- Stopping cigarette smoking.

- Education of the patient about the disease.

- Relief of bronchospasm.

- Chest physical therapy.

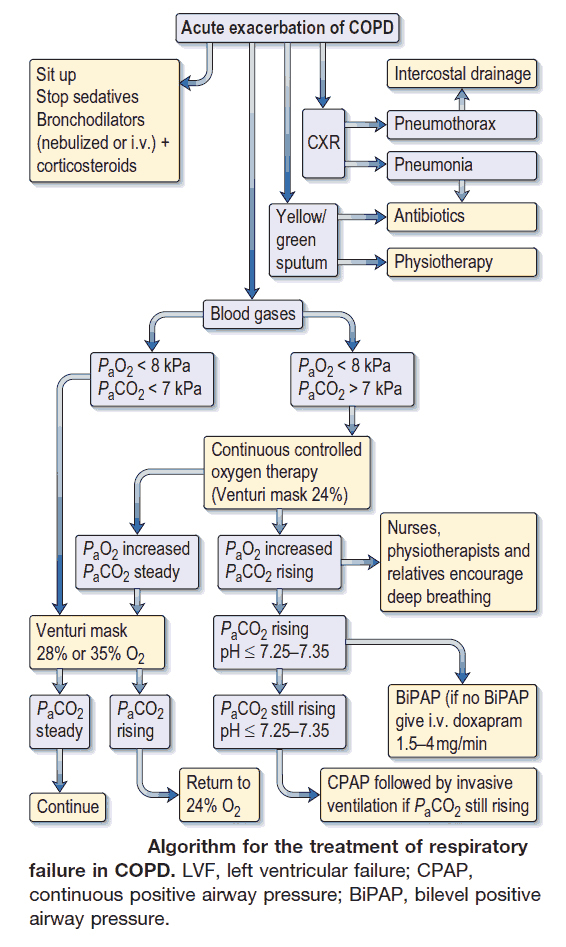

- Treatment of acute exacerbations.

- Treatment of cor pulmonale: if appropriate.

- Home oxygen therapy: when indicated.

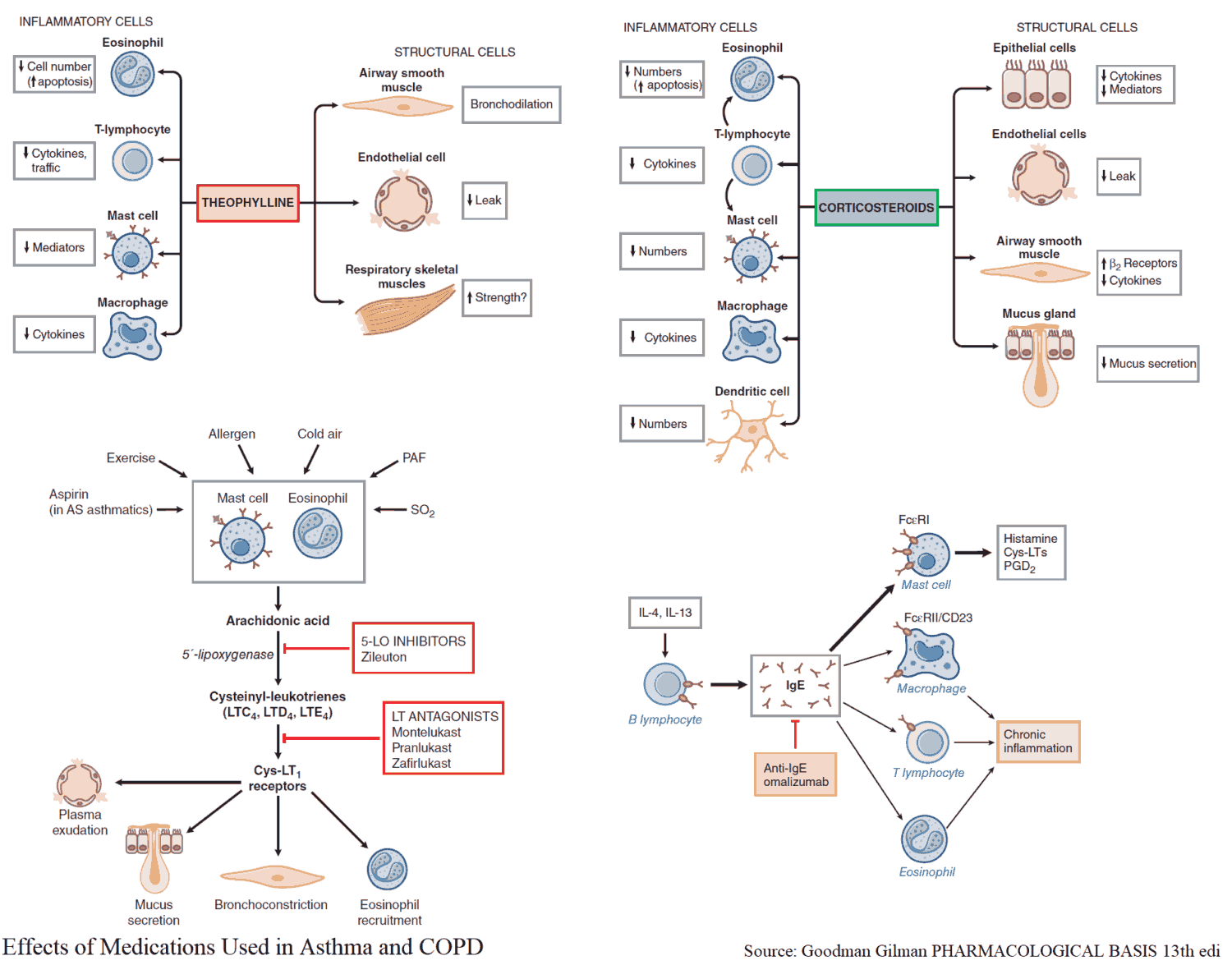

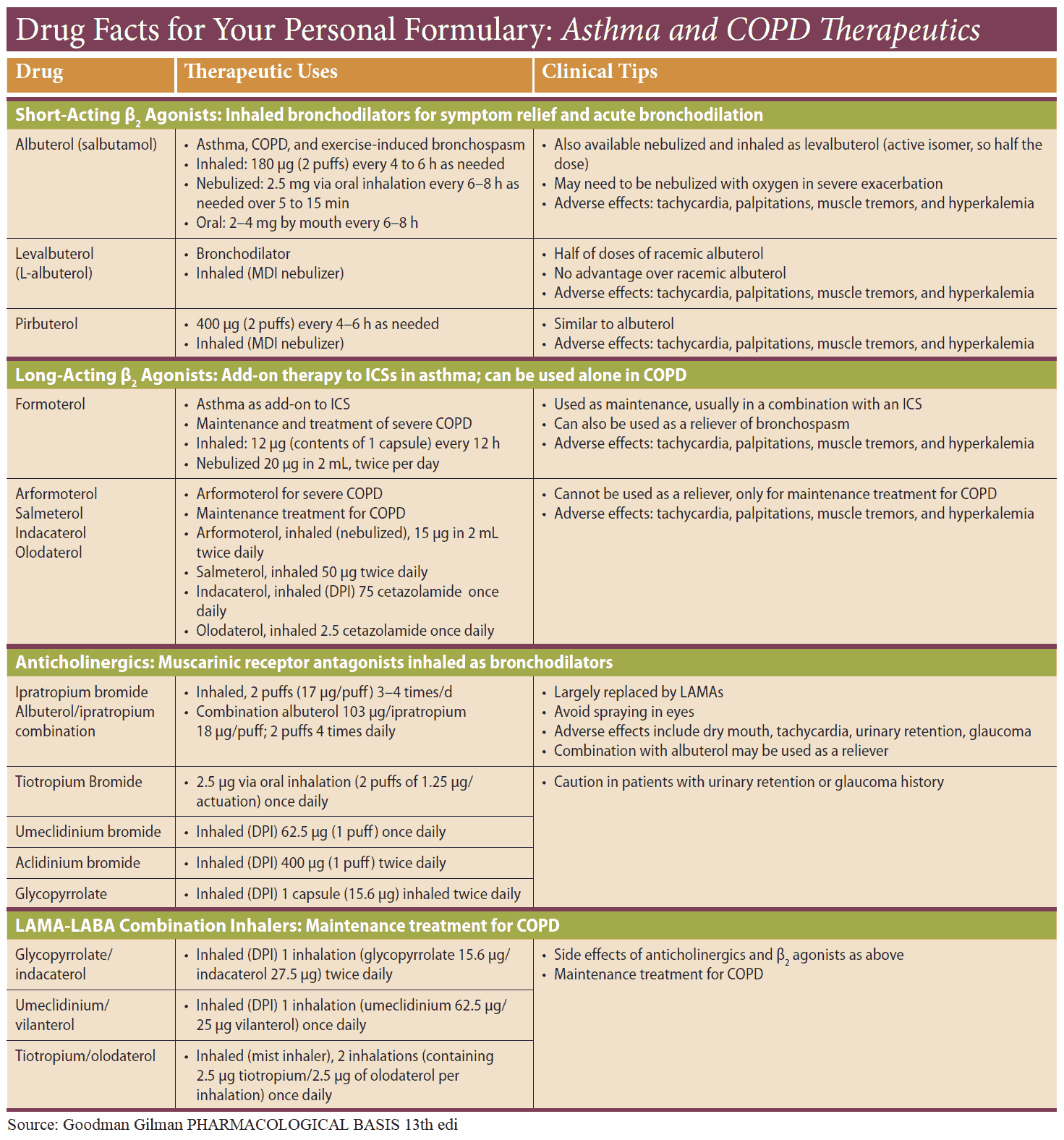

A trial of bronchodilator drugs is warranted in all patients with COPD. Although treatment follows a similar pattern to that seen in asthma, there are some differences.

Inhaled antimuscarinic bronchodilators (e.g., ipratropium) are considered first choice in COPD, often combined with a short-acting β2 agonist.

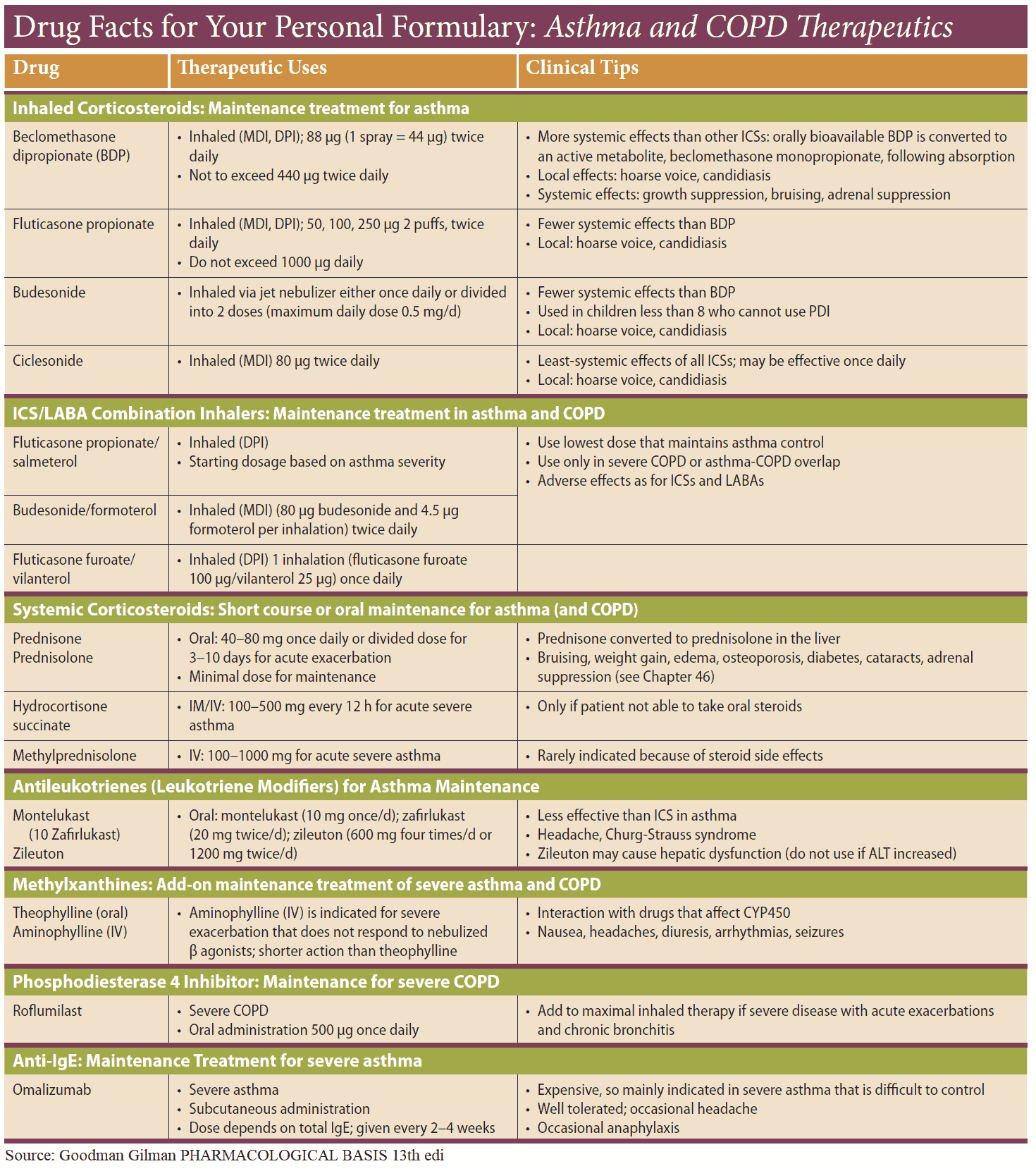

Oral corticosteroids or high-dose inhaled steroids play an important role in a small minority of patients (perhaps 10-15%) who respond to a corticosteroid trial. This usually consists of 3 weeks of prednisone at 30-40 mg/day with appropriate monitoring of the peak flow.

Infective exacerbations of COPD are treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics such as amoxicillin, trimethoprim, or tetracycline, aiming to cover the likely pathogens (pneumococci and Haemophilus influenzae).

Long-term administration of oxygen (at least 15 hours daily) may prolong survival in patients with severe COPD with cor pulmonale. Guidelines suggest that this treatment should be provided for patients who fulfil the following criteria:

- Ambulatory oxygen saturation monitoring <88% or partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) <55 mmHg.

- FEV1 <1.5 L and FVC (forced vital capacity) <2 L.

Blood gas measurements should be stable on two occasions at least 3 weeks apart after the patient has received appropriate bronchodilator therapy. Increased respiratory depression is seldom a problem in patients with stable respiratory failure treated with low concentrations of oxygen, although it may occur during exacerbations.

Patients and relatives should be warned to call for medical help if drowsiness or confusion occur. Oxygen concentrators, rather than cylinders, are more economical for patients requiring oxygen for long periods and are now used routinely.

Less information is available on long-term oxygen in patients with a similar degree of hypoxemia and airflow obstruction but no hypercapnia. The current advice is that these patients should not be denied home oxygen, but the effects of long-term therapy have not yet been fully assessed.