This post is an answer to the Case – Severe Pain and Edema of the Neck and Chest

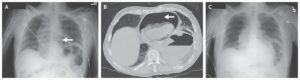

A CT examination was required to evaluate the neck and the chest. A large number of nails and stones were found along the gastrointestinal tract extending from the stomach to the rectum. A big stone was detected within the pharynx. Subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum was also seen. Patient was sent to the operating room immediately.

Differential Diagnosis List

- Ingested foreign bodies with oesophagus perforation from impacted stone

- Inhaled foreign body

- Mallory-Weiss tear

- Spontaneous pneumothorax

Final Diagnosis

Ingested foreign bodies with oesophagus perforation from impacted stone.

Discussion

Oesophageal foreign body impaction usually occurs in children, who tend to ingest coins, toys, or other foreign materials. In adults, foreign body impaction in the oesophagus is usually caused by an inadequately chewed bolus of food or bones. Unchewed food tends to lodge in a lower oesophageal ring or stricture, whereas bones tend to lodge in the pharynx near the cricopharyngeus.

Most patients with food impaction present with sudden onset of chest pain, odynophagia, or dysphagia. In contrast, young children usually exhibit respiratory distress, drooling, or regurgitation [1].

Oesophageal perforation is rare, affecting less than 1% of all patients with foreign body impaction, but the risk of perforation increases significantly if the impaction persists longer than 24 hours. After that, the risk for retropharyngeal abscess highly increases as well. Oesophageal perforation is a catastrophic condition that may rapidly progress to fulminant mediastinitis and septic shock.

The initial symptoms and signs include sudden onset of severe retrosternal chest pain, vomiting, and subcutaneous emphysema with crepitus in the soft tissues of the anterior chest wall (mediastinal crunch). In some cases, however, the initial signs and symptoms are nonspecific and may consist of hypotension, sepsis, or fever, falsely suggestive of myocardial infarction, acute aortic dissection, or intraabdominal abnormalities.

The prognosis is directly related to the interval between perforation and initiation of therapy; within 24 hours, the mortality rate for thoracic esophageal perforation exceeds 80%.

Plain radiography, especially lateral radiographs of the neck, may occasionally demonstrate bones or other radiopaque foreign bodies [1, 2].If we decide to administer oral CM we should always use hydrosoluble non ionic contrast agents to avoid the reaction of barium to the pleura or peritoneum.CT is also useful in evaluating oesophageal foreign body impaction. With its soft tissue and bone windowing, CT may replace the barium swallow because of its superior detection of thin, small, minimally calcified foreign bodies that are often obscured by overlying tissues. CT can also detect inflammatory changes in the adjacent structures.

CT features of oesophageal perforation include oesophageal wall thickening, perioesophageal fluid, perioesophageal air, pleural effusion, and pericardial effusion, oesophageal wall laceration, and extravasation of oral contrast material. Pleural effusions are usually bilateral. CT is ideally suited for defining the extent of extraluminal air-fluid collection and for detecting small amounts of extravasated contrast material. In addition, CT may also be useful in monitoring the clinical course of patients treated conservatively [3, 4, 5].

References

- Patton AS, Lawson DW, Shannon JM, et al (1979) Reevaluation of the Boerhaave syndrome. A review of fourteen cases. Am J Surg 137:560-565

- Jones 2nd WG, Ginsberg RJ (1992) Esophageal perforation: A continuing challenge. Ann Thorac Surg 53:534-543

- Backer CL, LoCicero 3rd J, Hartz RS, et al (1990) Computed tomography in patients with esophageal perforation. Chest 98:1078-1080

- de Lutio di Castelguidone E, Merola S, Pinto A, et al (2006) Esophageal injuries: Spectrum of multidetector row CT findings. Eur J Radiol 59:344-348

- Endicott JN, Molony TB, Campbell G, et al (1986) Esophageal perforations: The role of computerized tomography in diagnosis and management decisions. Laryngoscope 96:751-757