This article is an answer to the Case – A Woman With Thick, Pebbly, Warty Skin Changes on her Legs

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) — also called elephantiasis nostras, mossy leg, and lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica — is a troublesome complication of chronic lymphedema.

It most commonly occurs on the leg and scrotum in the setting of chronic lymphedema. In our practice we have also seen it frequently involve the pannus of extremely obese patients.

ENV is characterized by fibrosis and warty changes of the affected body part, which may become massively enlarged. The term “nostras” means “of our region,” and is used to indicate elephantiasis that is non-filarial in origin.

Worldwide, most lymphedema is caused by filarial nematodes (roundworms), such as Wucheria bancrofti that are transmitted by mosquito vectors. The filarial organisms infect the lymphatic system and during a 10- to 15-year period chronic changes of lymphedema develop, including hypertrophy of the affected area, warty skin changes and woody induration.

These changes are identical to those observed in ENV. In the case of filarial disease, this constellation of findings is simply called ‘elephantiasis.’

In developed countries, however, filarial disease is quite rare, and the elephantiasis skin changes are caused by non-filarial etiologies of lymphedema.

Lymphedema is classified in two categories primary or secondary. Secondary lymphedema is associated with underlying causes, including malignancy, infection or physical factors, such as obesity or surgery. In the United States, post-surgical secondary lymphedema – occurring for example in the setting of radical masectomy with lymph-node dissection – is most common.

Primary lymphedema may be congenital (present at birth), early-onset or late-onset. Other types of primary lymphedema are associated with various syndromes, such as Noonan syndrome and Turner syndrome. Milroy hereditary edema of the lower legs is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder, in which unilateral or bilateral lymphedema is present at birth.

Lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome, also an autosomal dominant disorder, consists of bilateral lower extremity lymphedema with distichiasis, the growth of extra eyelashes. Onset occurs in adolescence in contrast with Milroy’s disease, a hereditary edema that is present at birth.

Lymphedema praecox typically develops in females between the age of 9 and 25 years. The swelling initially involves the ankles, but subsequently extends to involve the entire leg. With time, fibrosis occurs and the swelling becomes permanent.

The secondary causes of lymphedema are many. When a malignancy involves the axillary or pelvic lymph nodes, lymphatic obstruction may lead to lymphedema in the extremity whose lymphatic channels drain into the affected nodes.

Additionally, lymphedema may develop after removal of lymph nodes, such as when an axillary lymph node dissection is performed in the surgical management of breast cancer.

Repeated episodes of bacterial cellulitis may also cause or worsen lymphedema. Obesity and chronic venous insufficiency/stasis are other risk factors for the development of chronic lower extremity lymphedema, and subsequent skin changes associated with ENV. In our patient, the combination of venous stasis, morbid obesity and recurrent cellulitis likely led to the development of ENV.

Stewart-Treves syndrome is also called ‘post-masectomy lymphangiosarcoma.’ This is angiosarcoma arising in the setting of chronic lymphedema, most commonly lymphedema of the arm secondary to axillary lymph node dissection. This is an aggressive malignancy, and metastases and death are common.

Lipedema is the bilateral and symmetric enlargement of the legs above the ankles due to fat deposition. It occurs most commonly in women with a family history of similar changes. ENV does not occur in Lipedema, because lipedema is not due to lymphedema.

Diagnosis & Treatment

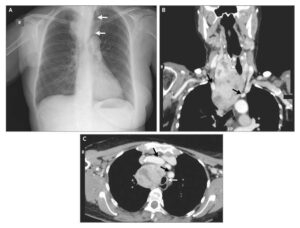

The diagnosis of ENV is usually made by the clinical recognition of warty and fibrotic skin changes in a chronically lymphedematous limb. In the United States, risk factors are obesity, chronic venous insufficiency and recurrent cellulitis. In tropical countries, the disease is commonly caused by filarial roundworms. Imaging and skin biopsy may confirm the diagnosis.

Most cases of ENV and chronic lymphedema are managed conservatively with various forms of compression therapy, including pumps, compression garments and manual lymphatic drainage techniques. Chronic antibiotic therapy may help prevent repeated cellulitis. Oral retinoids reportedly help improve some of the skin changes associated with ENV.