The 5,000 to 15,000 caustic ingestions (CI) per year in the United States occur in both children and adults. Eighty percent of these ingestions occur accidentally in children from 1 to 5 years old, and the rest typically occur intentionally in adults greater than 21 years old.

Serious ingestions can immediately result in perforation, shock, and even death. Intentional ingestions in adults tend to have more serious consequences. Long-term complications can lead to strictures and an increased risk of esophageal cancer.

In the emergency department (ED), we need to be aware of the atypical presentations of Caustic Ingestions in children and be prepared for the immediate resuscitation of high-volume ingestions in adults.

Caustic Materials

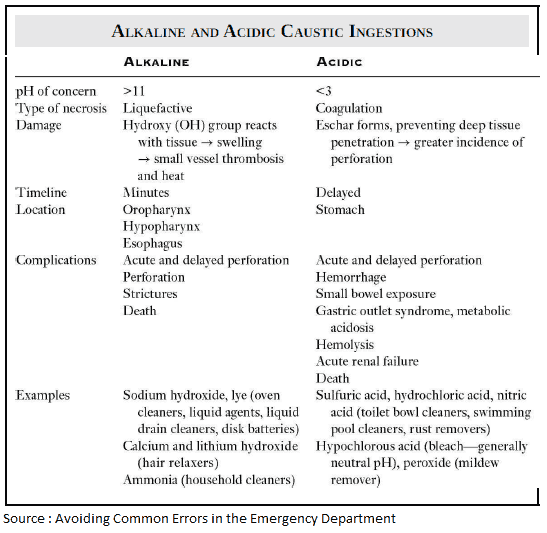

Caustic materials cause tissue injury by chemical reaction. These materials are generally acidic or alkaline. The severity of tissue injury is determined by pH, concentration, duration of contact, amount, and physical form of the ingested substance.

- Acids cause coagulative necrosis, which results in a self-limiting burn pattern

- Alkaline materials induce liquefactive necrosis with diffusion into deeper layers of the injured mucosa. Even low concentrations of alkaline ingestion can cause extensive injury.

Symptoms and Signs of Caustic Ingestion

Caustic Ingestion can provoke injury from the mouth, the airway, down through the esophagus to the small intestine. Depending on the quantity, intent, and timing of the caustic ingestion, patients may present with a myriad of symptoms.

- Obvious burns to the lips, mouth, and oropharynx may occur, but do not be fooled if these signs are not present.

- Adults with intentional ingestions without any oropharynx involvement may have significant esophageal involvement (think about a fast intentional ingestion, where the liquid does not burn the oropharynx).

- Laryngeal or epiglottic edema may present with:

- stridor

- dysphonia

- hoarseness

- dyspnea

- drooling

- respiratory distress and impending airway obstruction

- Severe Caustic Ingestion can cause esophageal perforation and may present with:

- abdominal pain

- rigidity

- substernal chest pain

- back pain

Diagnosing Caustic Ingestions

While the diagnosis is obvious when the history is clear, there are case reports of children presenting with symptoms of allergic reaction, being treated as anaphylaxis and later found to have a Caustic Ingestion.

Thus, in children presenting with allergic symptoms not improving with treatment, Caustic Ingestion should be considered in the differential, as the initial presentation is similar and otherwise can be easily missed.

Unfortunately, even if the clinician considers caustic ingestion, there is currently no definitive way to establish the diagnosis in the emergent setting if the ingestion is not reported.

Radiographs can help provide information regarding perforation but are not always diagnostic. Only through direct visualization (usually by endoscopy) can the definitive diagnosis of caustic ingestion be made.

When performed within the first 72 hours after ingestion, endoscopy stages pathology and identifies the need for further intervention. If patients have any oropharyngeal injury, drooling, vomiting, dysphasia, or pain, a high-grade injury is likely, and urgent endoscopy should be performed to determine if surgical intervention is required.

Management of Caustic Ingestion

What to avoid ?

- Avoid agents that induce vomiting, such as ipecac, as this can lead to esophageal perforation.

- Avoid attempting to neutralize the substance by using a weak acid or base as this can result in further injury.

- Avoid diluents.

- Avoid activated charcoal, because of poor adsorption and endoscopic interference.

When managing CI, remember to evaluate the patient’s airway first. Equipment for endotracheal intubation and cricothyrotomy should be readily available. If significant edema is present, consider fiberoptic-assisted intubation.

Always place the patient NPO (nothing by mouth) until the extent of injury can be determined.

If a suicide attempt is suspected, consider ethanol, salicylate, and acetaminophen levels as well as a psychiatric evaluation. In some cases, salicylate ingestion has been shown to independently cause stricture formation.

With large-volume liquid acid ingestions, nasogastric tube suction may be beneficial, but its use needs to be weighed against the risk of esophageal perforation.

Aggressive hydration and medications to decrease acid production are given to prevent reflux associated injury, while steroids remain controversial.

Key Points

- Do NOT induce emesis, use ipecac, give charcoal, or attempt to neutralize the ingested substance by using a weak acid or base.

- In children: consider CI in patients who present with symptoms of anaphylaxis that do not improve with treatment.

- Endoscopy is indicated within 24 to 48 hours for any patient who is symptomatic (or asymptomatic with an alkali), children refusing to eat or drink, or patients with altered mental status.

References / Suggested Readings

- Bonnici KS, Wood DM, Dargan PI. Should computerised tomography replace endoscopy in the evaluation of symptomatic ingestion of corrosive substances? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(9):911–925.

- Lupa M, Magne J, Guarisco JL, Amedee R. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of caustic ingestion. Ochsner J. 2009;9(2):54–59.

- Sherenian MG, Clee M, Schondelmeyer AC, et al. Caustic ingestions mimicking anaphylaxis: Case studies and literature review. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e547–e550.

- Waasdorp Hurtado CE, Kramer RE. Salicylic acid ingestion leading to esophageal stricture. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(2):146–148.