Table of Contents

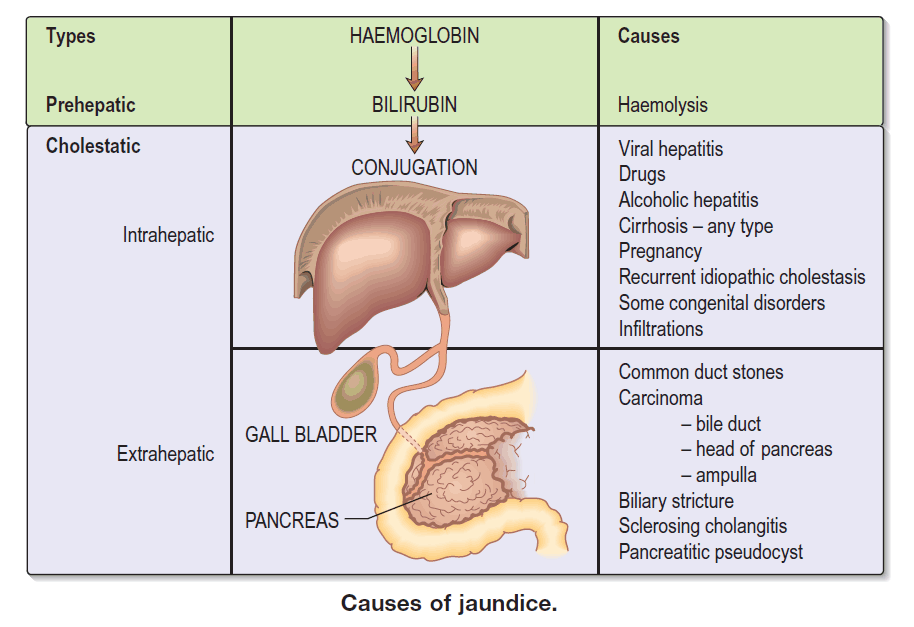

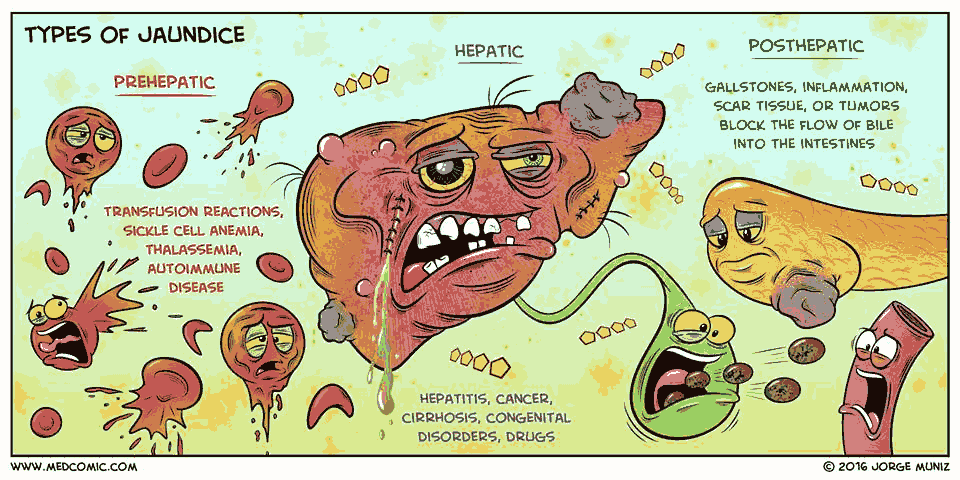

Jaundice (icterus) is the yellow discoloration of the skin, sclera, and mucosae, which is detectable when serum bilirubin concentrations exceed approximately 2.5 mg/dL.

Jaundice can arise as a result of increased red blood cell (RBC) breakdown, disordered bilirubin metabolism, or reduced bilirubin excretion.

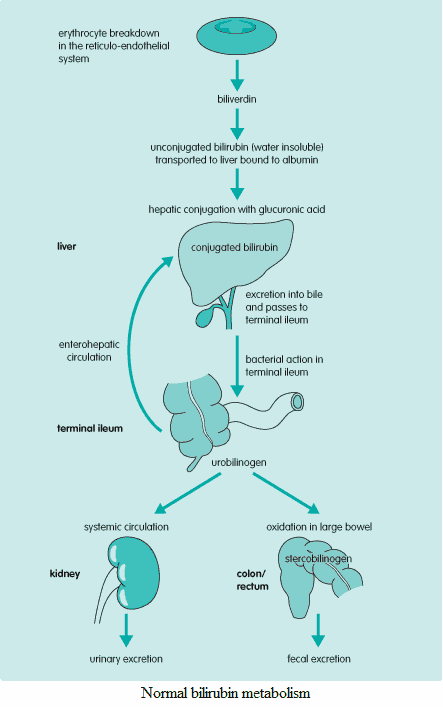

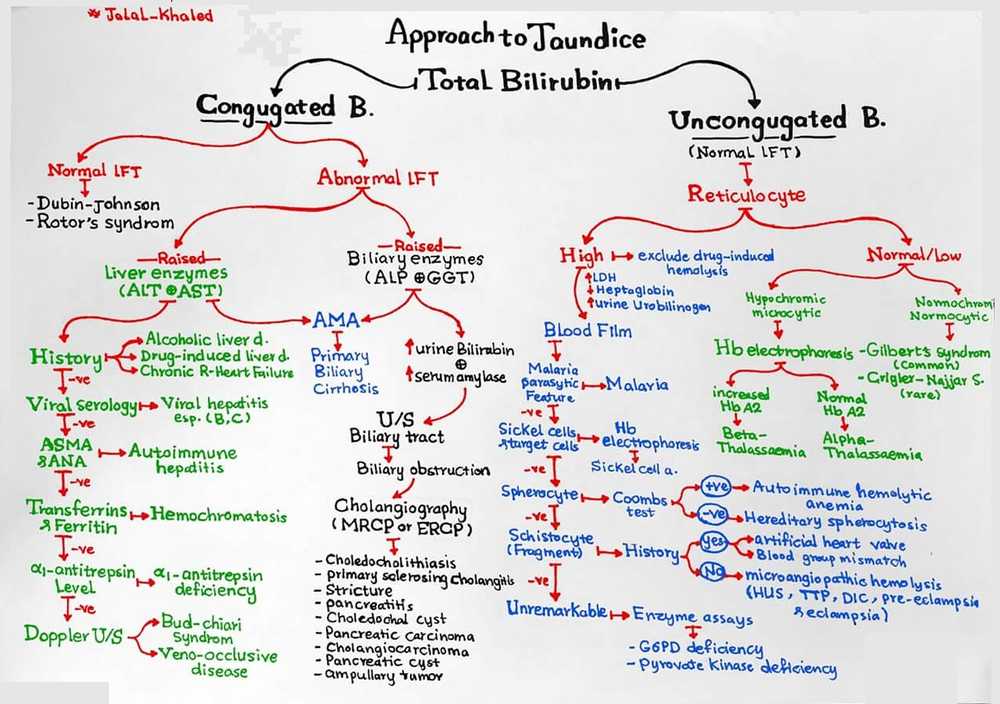

It is important to remember the two types of bilirubin: direct and indirect.

- The indirect (or unconjugated) bilirubin has yet to be transformed by the liver.

- The direct (or conjugated) bilirubin has already undergone post-production modification in the liver. This post-production processing in the liver provides a way to differentiate between pre- and intra-/post-hepatic causes of hyperbilirubinemia.

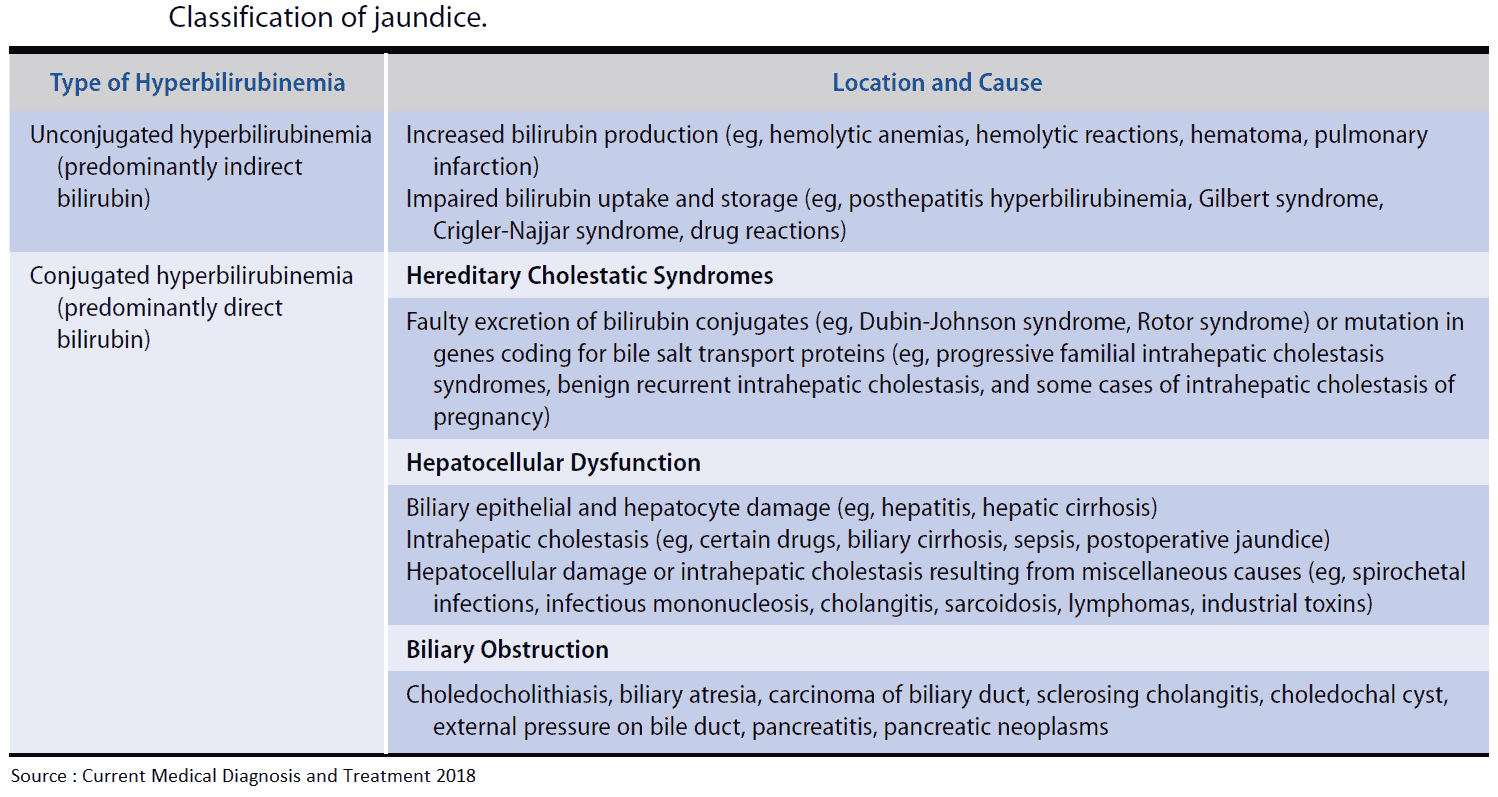

Differential Diagnosis of Jaundice

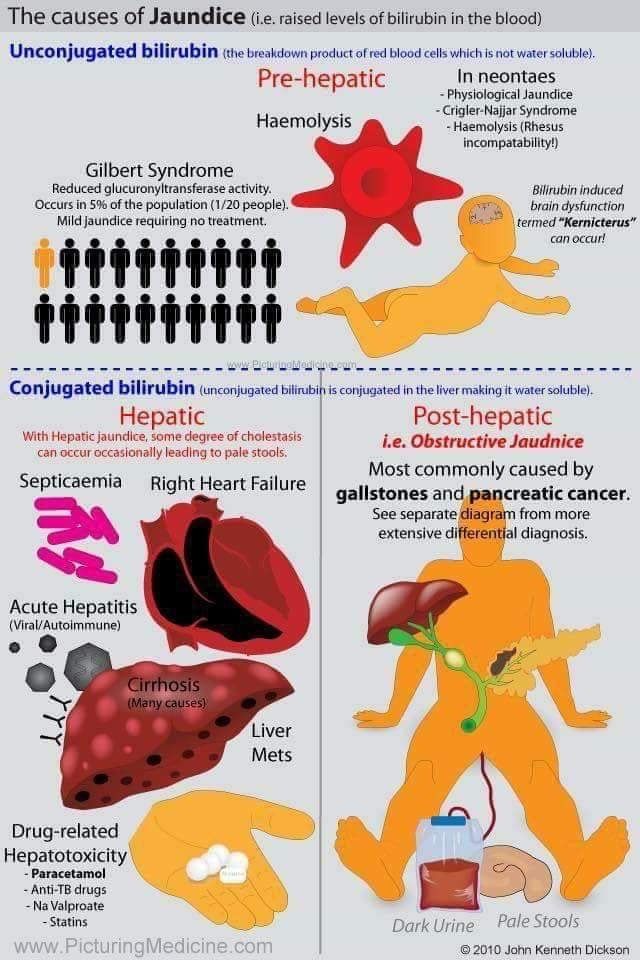

Prehepatic

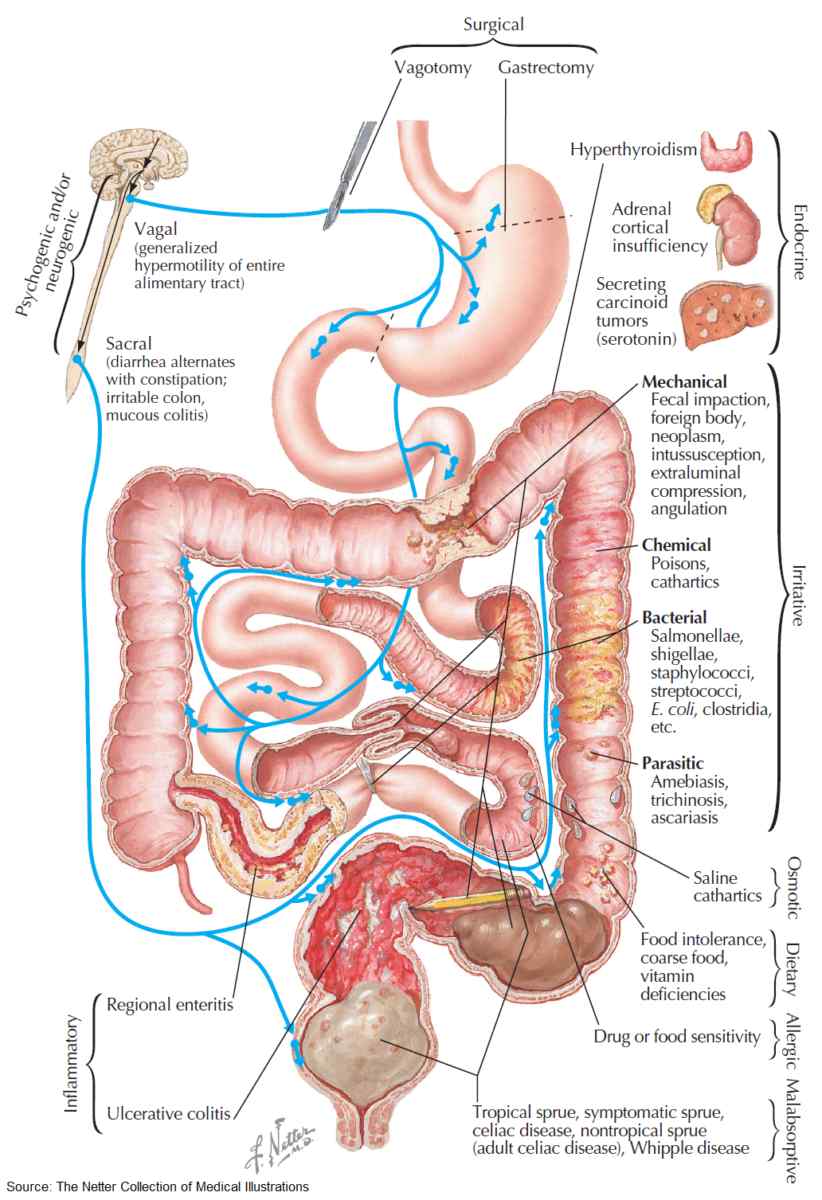

Prehepatic jaundice results from increased bilirubin production, caused by abnormal RBC breakdown (hemolysis). Chronic TPN can also cause hyperbilirubinemia.

Intrahepatic

Disordered bilirubin metabolism resulting from hepatocyte dysfunction may also cause jaundice. Hepatocellular damage can arise as a consequence of the following acute insults or chronic pathologies.

Acute hepatocellular damage

- Viral infection (e.g., hepatitis A, B, C and E; Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]; cytomegalovirus [CMV]).

- Nonviral infection (e.g., Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae).

- Drugs (e.g., acetaminophen poisoning, halothane).

- Alcohol.

- Pregnancy.

- Autoimmune liver disease.

- Shock.

Chronic hepatocellular damage

- Chronic active hepatitis (e.g., autoimmune disease, hepatitis B, hepatitis C).

- Cirrhosis (e.g., alcohol, chronic active hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency).

- Metastatic carcinoma.

Posthepatic

Posthepatic jaundice is caused by reduced bilirubin excretion. This may be due to intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary obstruction.

Extrahepatic obstruction

- Gallstones.

- Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas, ampulla of Vater or bile duct.

- Sclerosing cholangitis.

- Stricture (e.g., postendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [post-ERCP]).

- Pancreatitis.

- Parasitic infections (Stronglyoides sp.).

- Biliary atresia.

Intrahepatic obstruction

- Primary biliary cirrhosis.

- Alcohol.

- Viral hepatitis.

- Drugs (e.g., oral contraceptive pill).

- Pregnancy.

- Sepsis causing intrahepatic cholestasis.

- Postsurgical cholestasis.

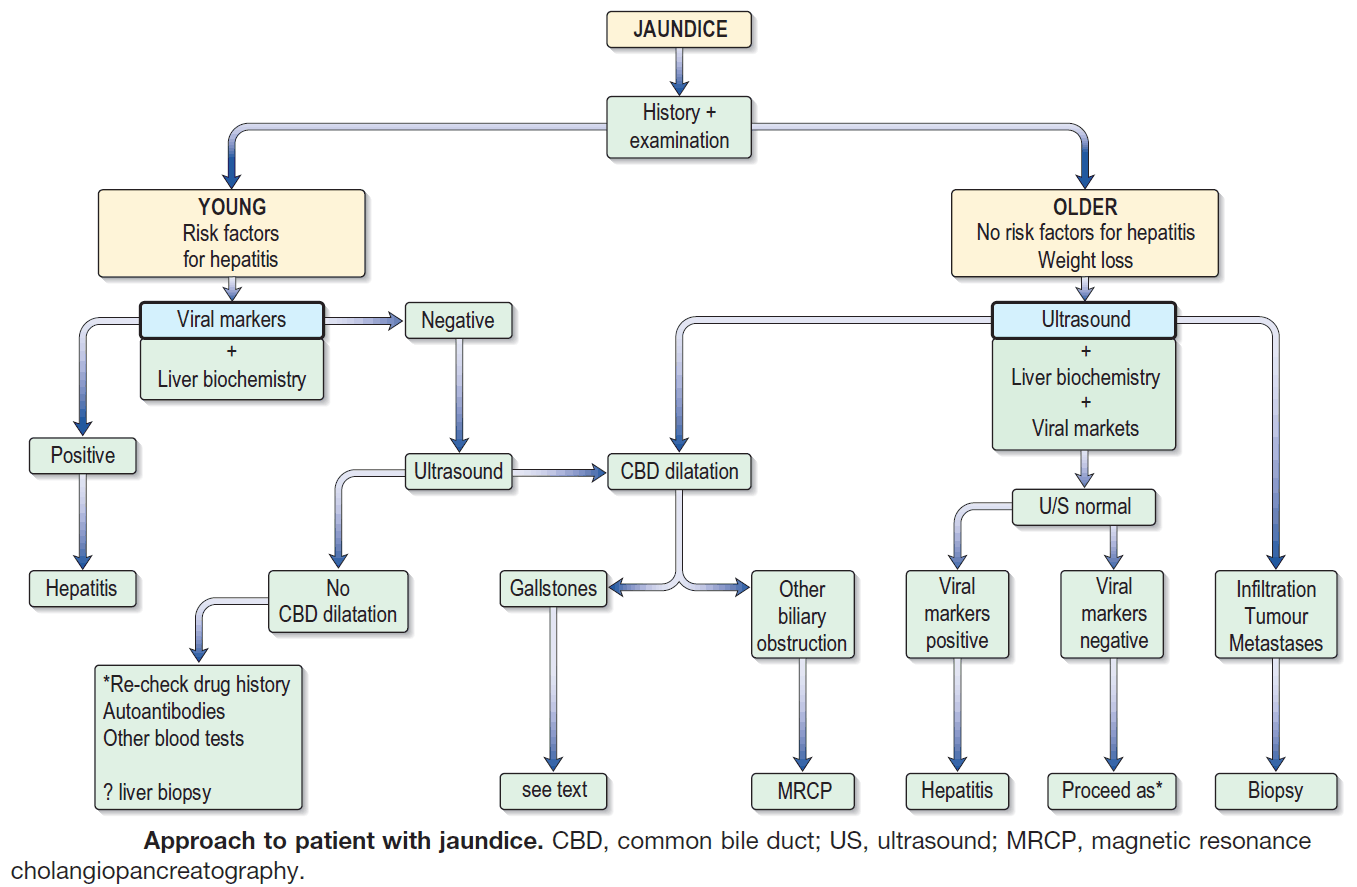

History in the patient with jaundice

The following factors should be assessed when obtaining a history in a patient with jaundice:

- Pruritus, dark urine, and pale stools: underlying cholestasis.

- Duration of illness: a short history of malaise, anorexia and myalgia are suggestive of viral hepatitis. If there is a prolonged history of weight loss and anorexia in an elderly patient, carcinoma is more likely.

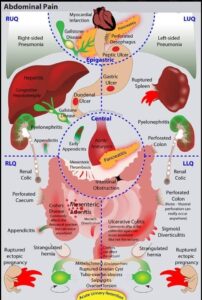

- Abdominal pain: the episodic, colicky, right upper quadrant pain of biliary colic will commonly be due to gallstones. A dull, persistent epigastric or central pain radiating to the back may suggest a pancreatic carcinoma.

- Fevers or rigors: cholangitis.

- Full recent drug history: particularly acetaminophen, oral contraceptive pill.

- Alcohol consumption: acute alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis.

- Infectious contacts: hepatitis A. Recent foreign travel to areas of high hepatitis risk. Malaria can also cause a hemolytic anemia. Parasitic infection can cause liver abscesses and obstruction of the biliary system.

- Recent surgery: halothane exposure, surgery for known malignancy, biliary stricture due to previous ERCP.

- Intravenous drug abuse, tattoos, homosexuality: increased risk of hepatitis B and C.

- Occupation: sewage workers are at an increased risk of leptospirosis.

- Family history of recurrent jaundice: inherited hemolytic anemias, Crigler-Najjar syndrome, and Gilbert’s syndrome, which can cause an increase in indirect bilirubin, and Rotor syndrome and Dubin-Johnson syndrome, which lead to direct hyperbilirubinemia.

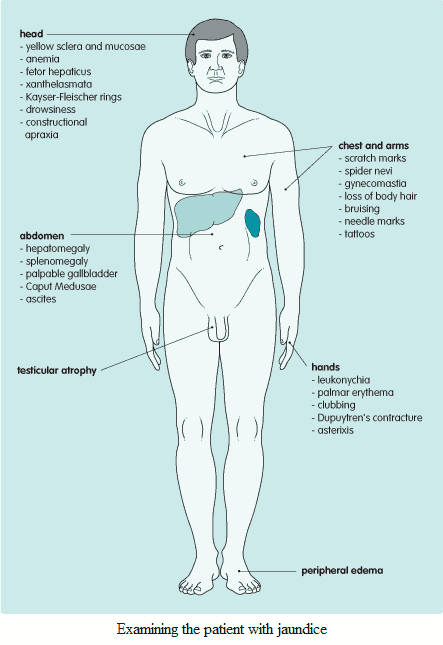

Examination and Signs in the Patient with Jaundice

There are three important groups of abnormalities that should be looked for in the jaundiced patient:

- How severe is the jaundice? Is there any evidence of encephalopathy?

- Is this an acute or chronic problem? (Are there any signs of chronic liver disease?)

- Are there any signs of specific disorders?

Is there evidence of encephalopathy?

The following factors suggest the presence of encephalopathy:

- Drowsiness: this will eventually progress through stupor to coma.

- Slurred speech.

- Asterixis: flapping tremor of outstretched hands.

- Seizures.

- Constructional apraxia (inability to perform purposeful movements): test by asking the patient to copy a five-pointed star.

- Hepatic fetor (patient smells like a freshly opened corpse-a smell that all medical students surely know).

Hepatic encephalopathy can arise as a result of fulminating acute liver failure or when chronic disease decompensates. Precipitating factors include:

- acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- infection (particularly peritioneal)

- high-dietary protein

- drugs (e.g., diuretics, sedatives)

- fluid and electrolyte disturbance

Are there any signs of chronic liver disease?

There are few clinical signs specific to acute liver disease. However, the following signs may commonly be found when liver pathology is longstanding:

- Palmar erythema.

- Leukonychia: hypoalbuminemia.

- Clubbing.

- Dupuytren’s contractures: particularly in alcoholic cirrhosis.

- Spider nevi: greater than five in the distribution of superior vena cava.

- Scratch marks: cholestasis (deposition of bile acids in the dermis leads to pruritus).

- Loss of body hair.

- Gynecomastia: elevated estrogen, spironolactone, testicular atrophy.

- Bruising: disordered coagulation.

- Hepatomegaly: not in well-established cirrhosis.

- Splenomegaly and caput Medusae: portal hypertension.

- Testicular atrophy: elevated estrogen.

- Edema: hypoalbuminemia.

Are there any signs of specific diseases?

- Xanthelasmata: primary biliary cirrhosis.

- Kayser-Fleischer rings: Wilson’s disease.

- Slate-gray pigmentation: hemochromatosis.

- Hard, irregular hepatomegaly: malignant metastases.

- Palpable gallbladder: carcinoma of head of pancreas (Courvoisier’s law).

- Splenomegaly: portal hypertension, viral infection.

- Needle marks or tattoos: hepatitis B, C.

Investigating and Diagnosing the Patient with Jaundice

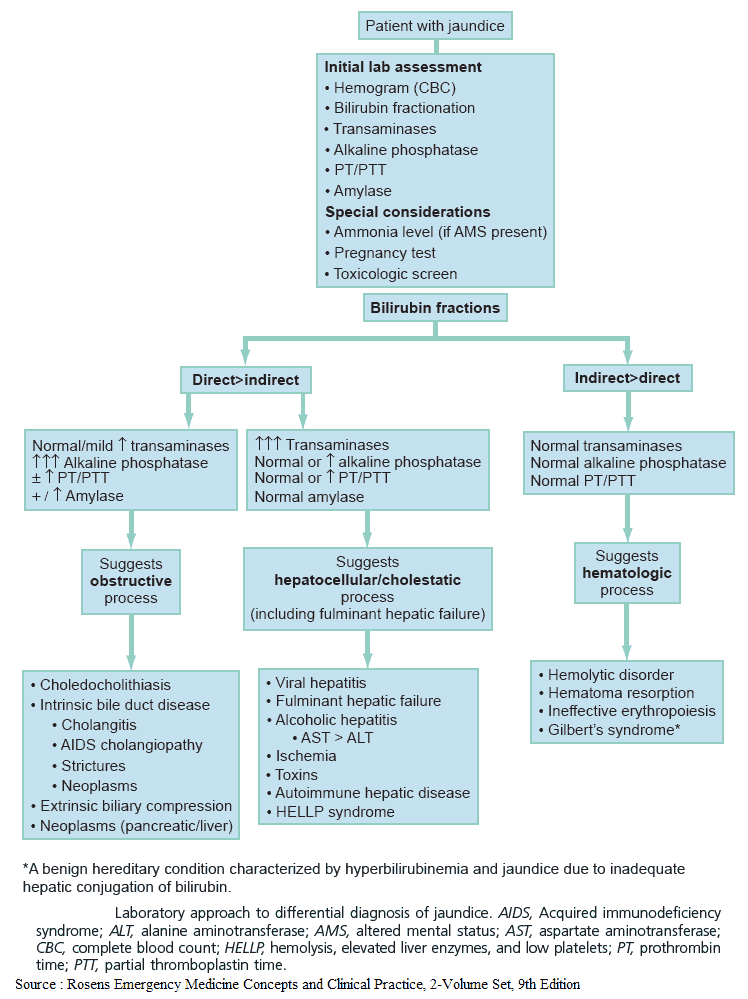

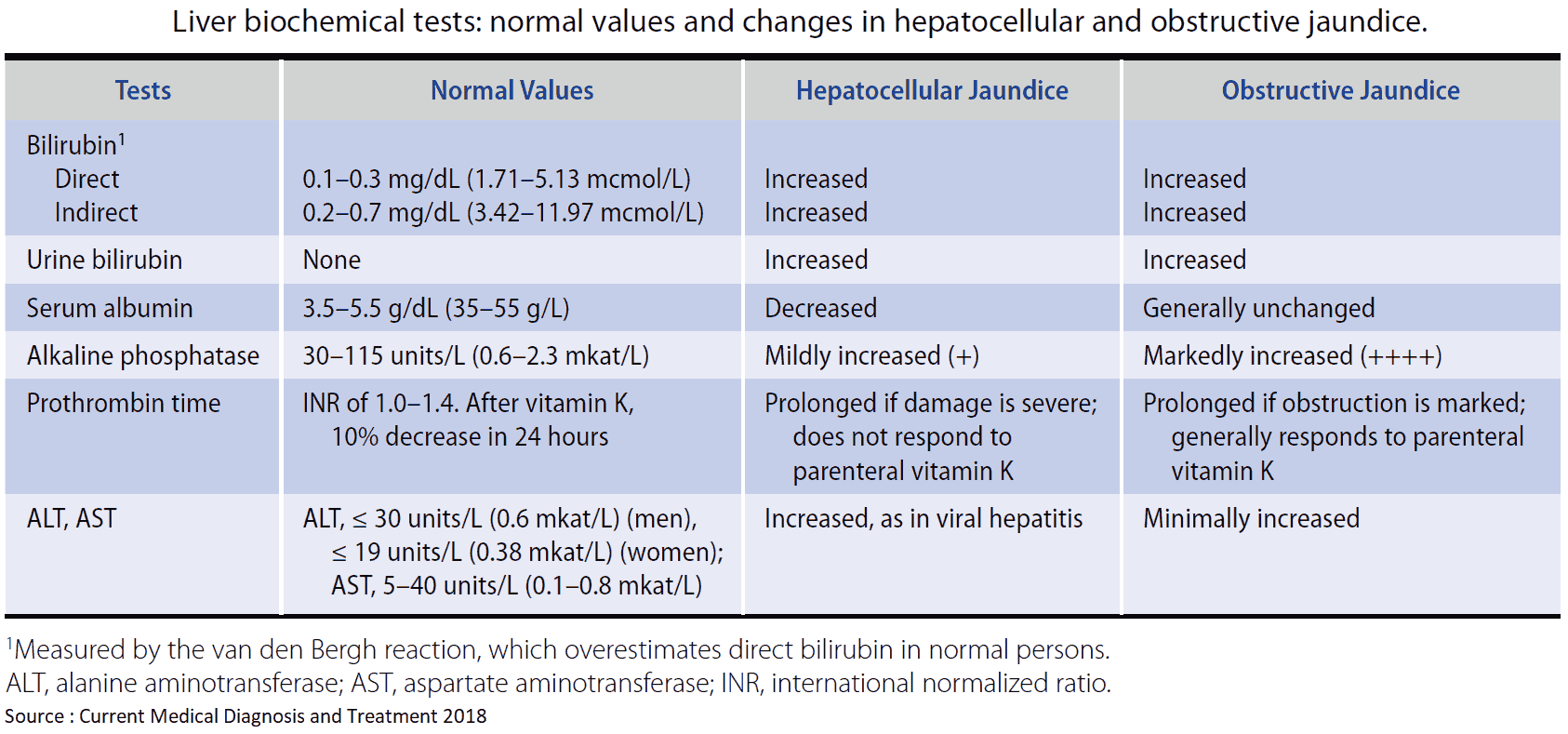

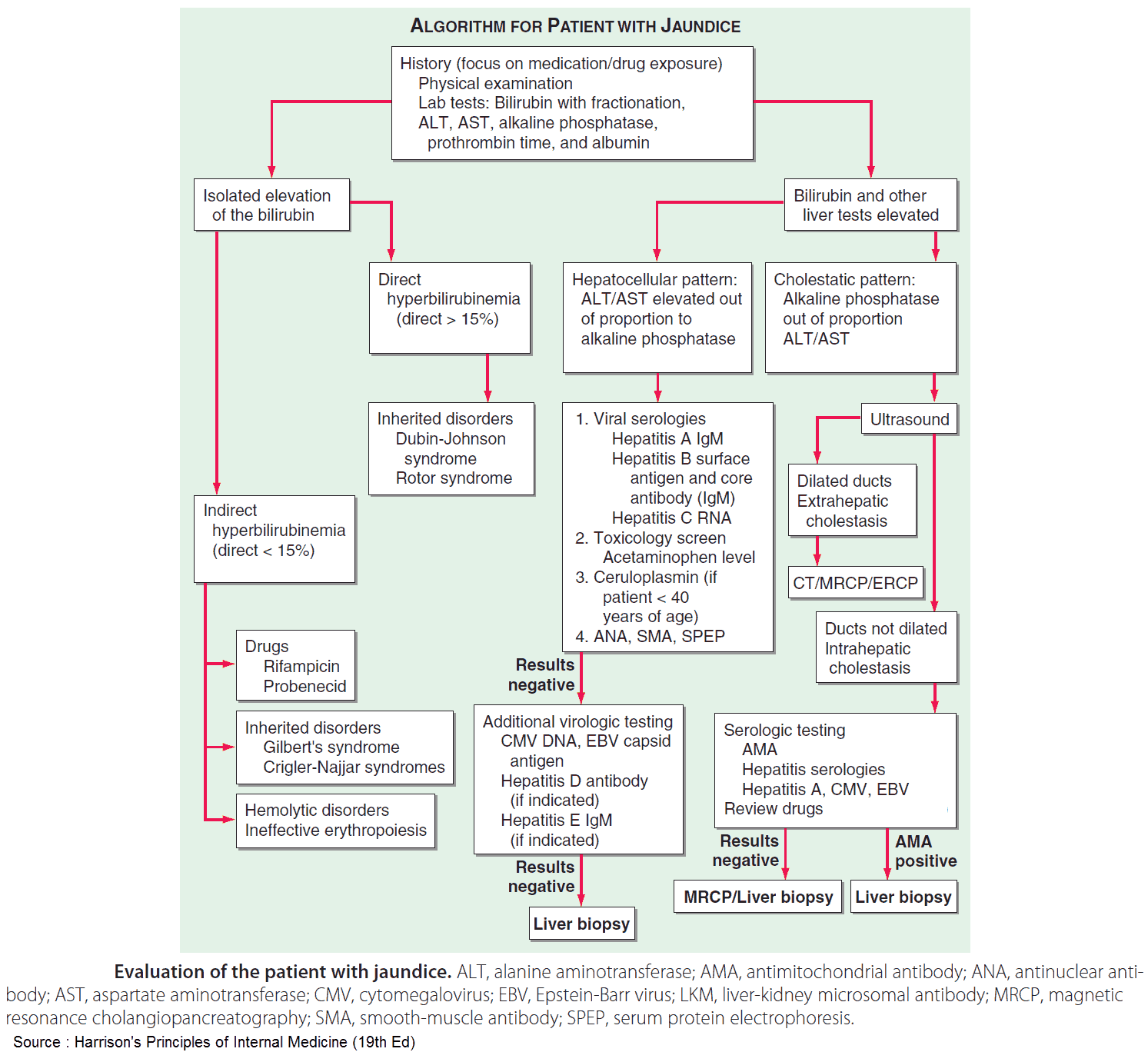

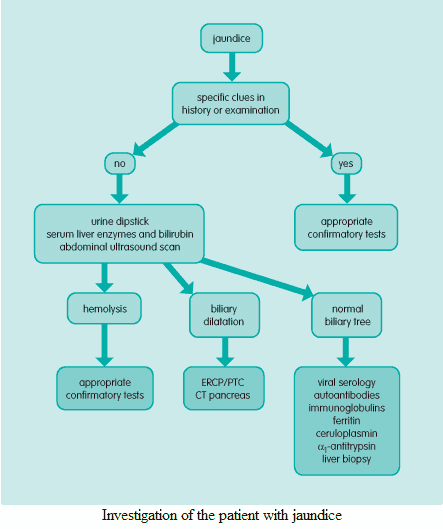

The investigation of jaundiced patients falls into two stages. Firstly, the type of jaundice must be determined (prehepatic, intrahepatic, posthepatic). Then more detailed tests should be performed to determine the specific etiology.

Establish the type of jaundice

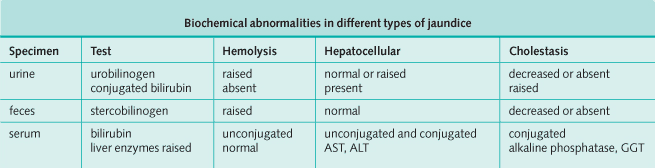

Quantification of urinary urobilinogen and conjugated bilirubin, along with measurement of serum liver enzymes-alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and γ-glutamyltransferase and bilirubin (both direct and indirect) will give a reasonable indication as to the type of abnormality present.

Abdominal ultrasound scan is then essential to exclude biliary obstruction. Albumin measurement and/or prothrombin time will show how dramatically, if at all, the liver’s synthetic function is compromised.

Tests to determine specific etiology

Hemolysis screen

Hepatocellular screen

- Viral serology: hepatitis A, B, and C; EBV, CMV.

- Autoantibody screen: antimitochondrial antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, ESR.

- Ferritin: hemochromatosis.

- Serum ceruloplasmin and urinary copper excretion:

- Wilson’s disease. α1-antitrypsin.

- Liver biopsy: definitive diagnostic test for intrinsic liver disease.

Cholestasis screen

- ERCP and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography: detailed information regarding the biliary tree; also used to perform therapeutic maneuvers such as stent insertion.

- RUQ ultrasound/Doppler should always be performed to look for signs of portal vein thrombosis, gallstones, liver parenchyma, and signs of ascites.

- Computed tomography scan: good images of the pancreas, which is often poorly visualized on an ultrasound scan.