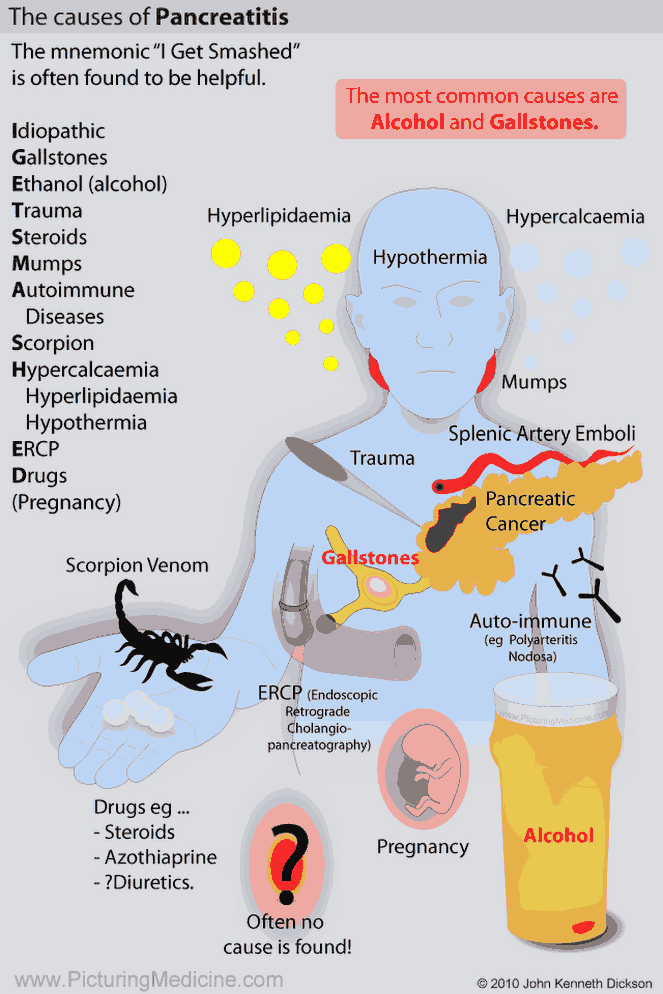

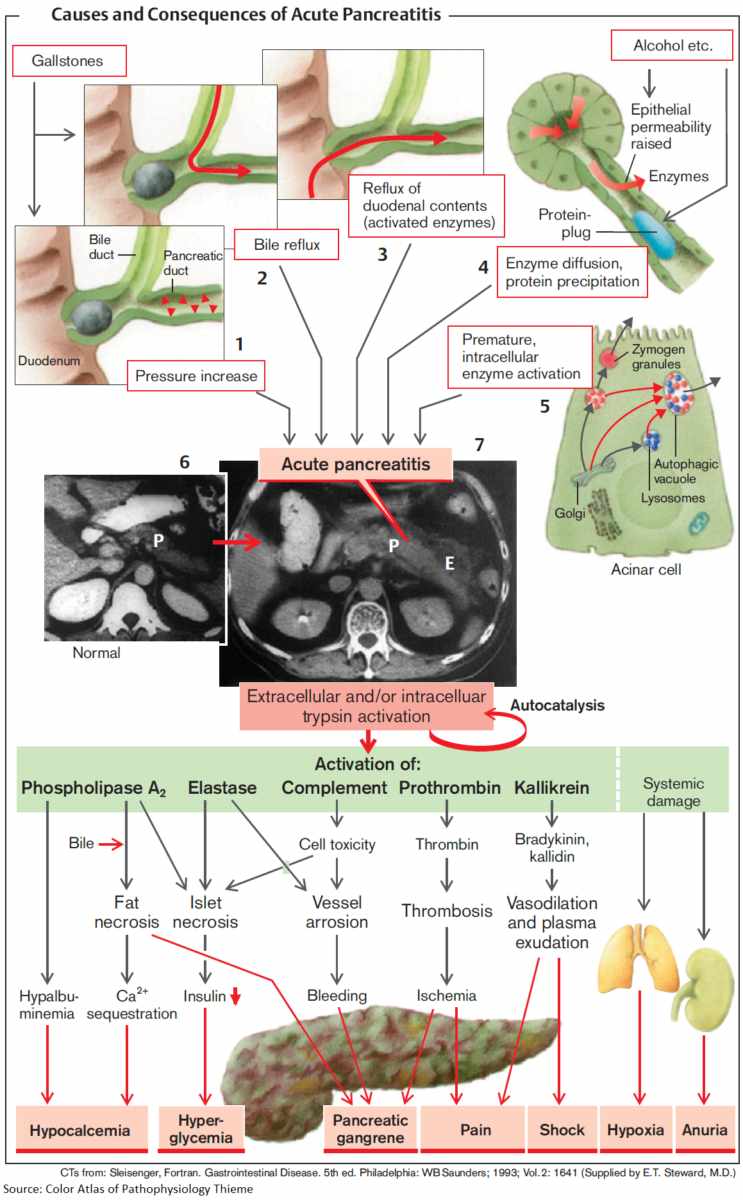

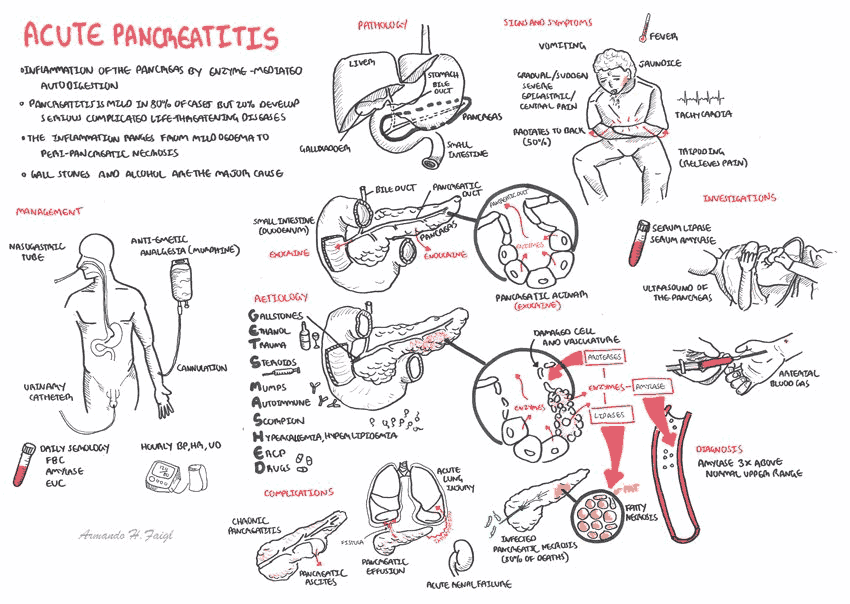

Etiology of Acute Pancreatitis

Causes of Acute Pancreatitis include:

- Gallstones (most cases)

- Alcohol (most cases)

- Idiopathic

- Hypercalcemia

- Hyperlipidemia

- Autoimmune

- Post ERCP

- Trauma

- Mumps

- Drugs (e.g., azathioprine,steroids or diuretics)

The causes of acute pancreatitis can be recalled from the mnemonic GET SMASH’D: gallstones, ethanol, trauma, steroids, mumps, autoimmune diseases, scorpion stings, hypertriglyceridemia, and drugs (e.g., azathioprine or diuretics).

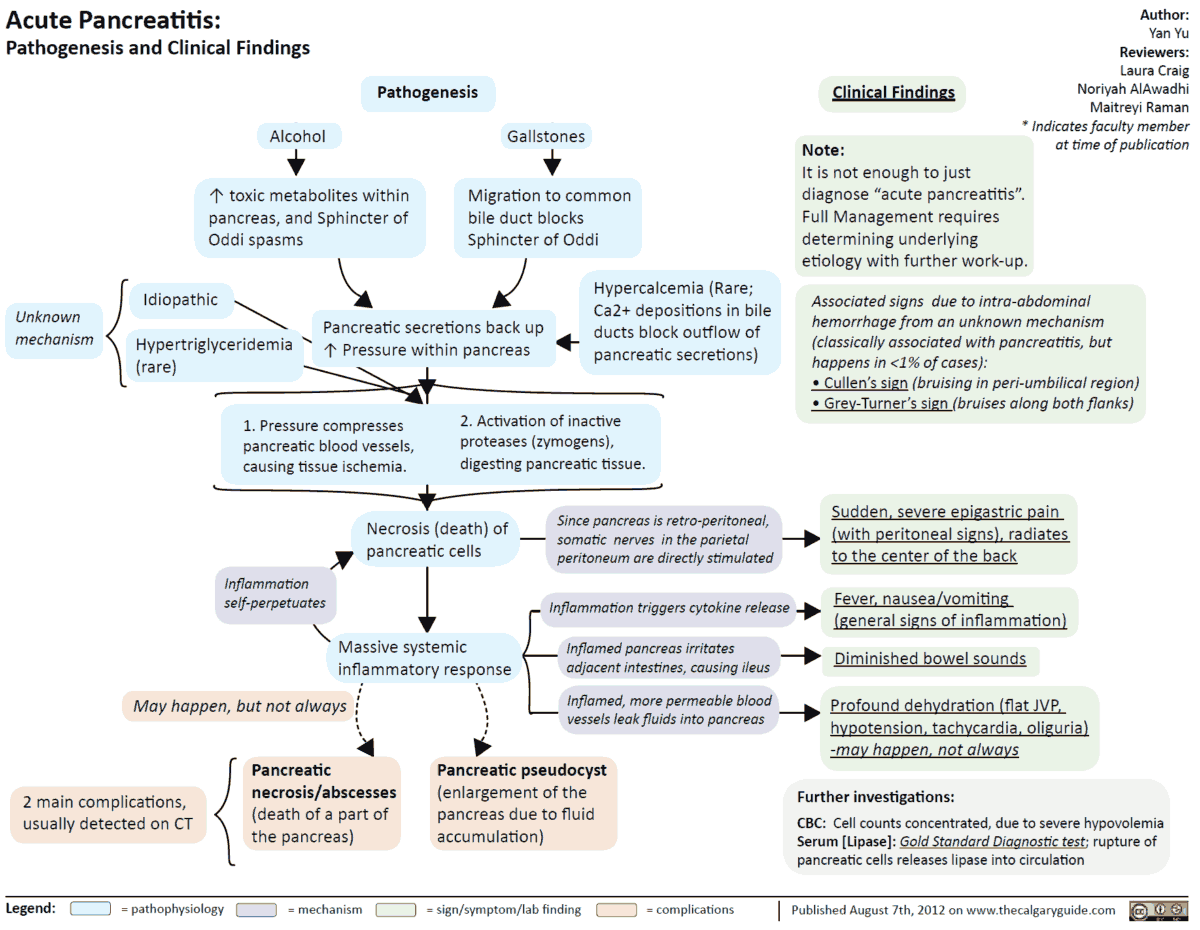

Clinical Features of Acute Pancreatitis

There may be a history of cholecystitis or other complications of gallstones. Alcohol intake should be ascertained.

The patient complains of:

- Severe abdominal pain radiating to the back or shoulder, which may be relieved by sitting forward

- There may be associated nausea and vomiting

On examination there is:

- abdominal tenderness with guarding and rebound tenderness

- tachycardia

- fever

- jaundice

- hypotension, and sweating

- bruising around the umbilicus (Cullen’s sign) or in the flanks (Grey-Turner’s sign)

Differential Diagnosis

- Any cause of an acute abdomen (e.g., cholecystitis, mesenteric ischemia, and intestinal perforation).

- Myocardial infarction

- Dissecting aortic aneurysm

Investigations

The following investigations are important in the patient with acute pancreatitis:

- Serum amylase: markedly raised (over 1000 IU/mL). Amylase is also raised with cholecystitis and perforated peptic ulcer, but usually to a lesser extent. Serum lipase is also elevated and is more specific than amylase.

- Abdominal x-ray: gallstones, pancreatic calcification indicating previous inflammation, an absent psoas shadow due to retroperitoneal fluid, and a distended loop of jejunum (“sentinel loop”).

- Serum calcium: may be low.

- White cell count: usually raised.

- ECG: to exclude myocardial infarction.

- Arterial blood gases: metabolic acidosis.

- CXR: widened mediastinum in aortic dissection; gas under the diaphragm in perforated peptic ulcer.

- Abdominal CT: assess severity.

READ MORE: Imaging of Acute Pancreatitis – to Image or Not to Image

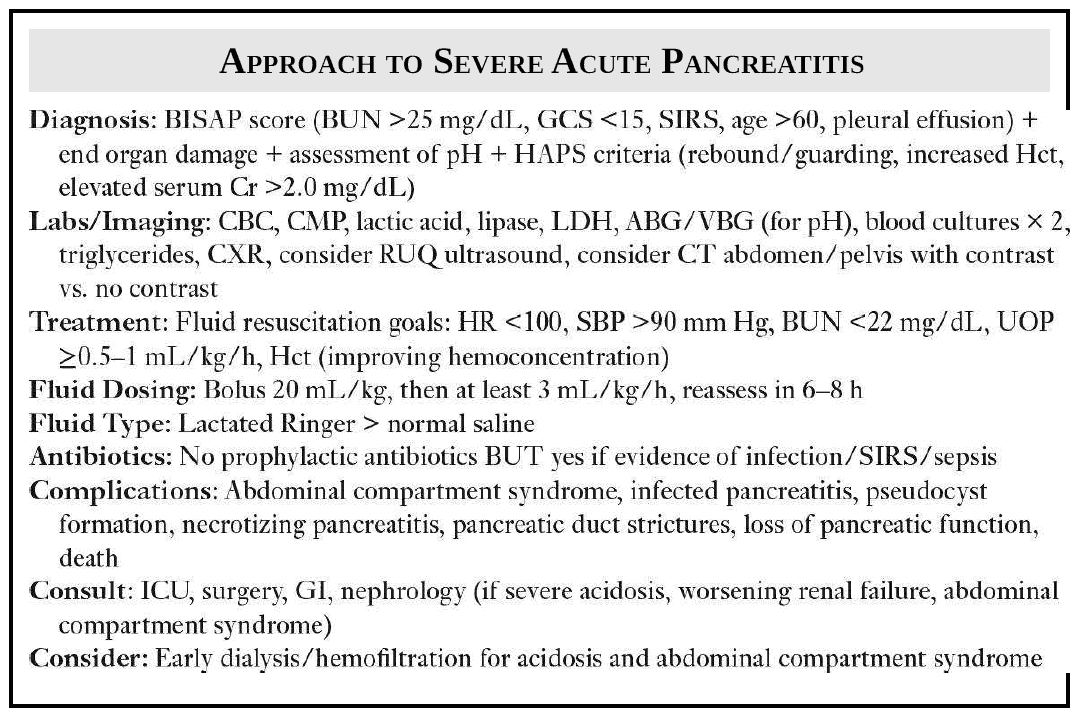

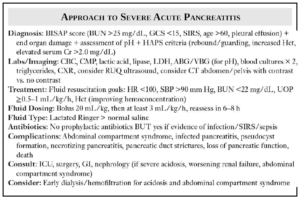

Management of Acute Pancreatitis

Management is usually conservative.

- Intravenous fluids should be given to maintain the circulating volume, and a central venous catheter may be helpful for assessing the volume of fluid required. If the patient is in shock (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg), plasma expanders will be required.

- Pain relief is with intravenous or intramuscular opiates (e.g., pethidine, 50-150 mg 4 hourly, or pentazocine, 30-60 mg 4 hourly, meperidine, fentanyl, or morphine with an antiemetic such as prochlorperazine, 12.5 mg 8 hourly).

- A nasogastric tube should be inserted. TPN may be required.

- Blood tests, especially metabolic panel, glucose, and calcium, should be monitored.

- Surgery should be considered for suspected hemorrhagic necrosis of the pancreas.

- Some give H2-receptor antagonists, prophylactic antibiotics, or peritoneal lavage, although these measures are of unproven value.

READ MORE: Recognizing and Treating Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP)

Complications and Prognosis

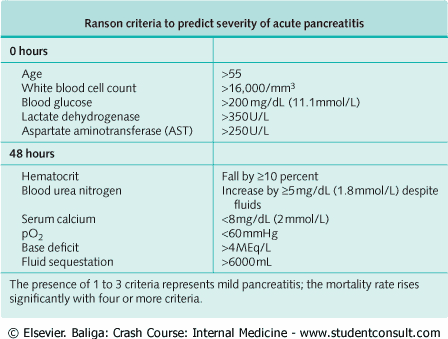

Ranson’s criteria are used to predict the severity of acute pancreatitis. Mortality is 5-10%, but recurrence is uncommon in patients who recover.

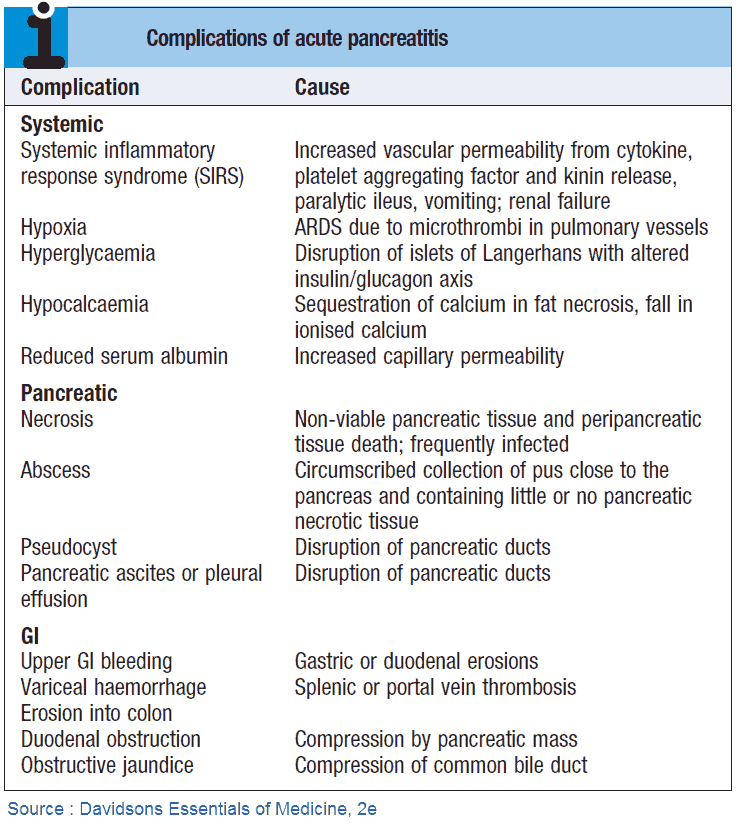

Complications include :

- shock

- renal failure

- sepsis

- respiratory failure

- hypocalcemia due to the formation of calcium soaps

- transient hyperglycemia

- pancreatic abscess requiring drainage

- pseudocyst (i.e., fluid in the lesser sac presenting as a palpable mass)

- persistently raised serum amylase or liver function tests, and fever

Patients should be investigated to exclude gallstones, and alcohol should be avoided.