Table of Contents

Peptic ulcer disease most commonly occurs in the duodenum, followed by the stomach, esophagus, and jejunum in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, or after a gastroenterostomy, or in a Meckel’s diverticulum with ectopic gastric mucosa.

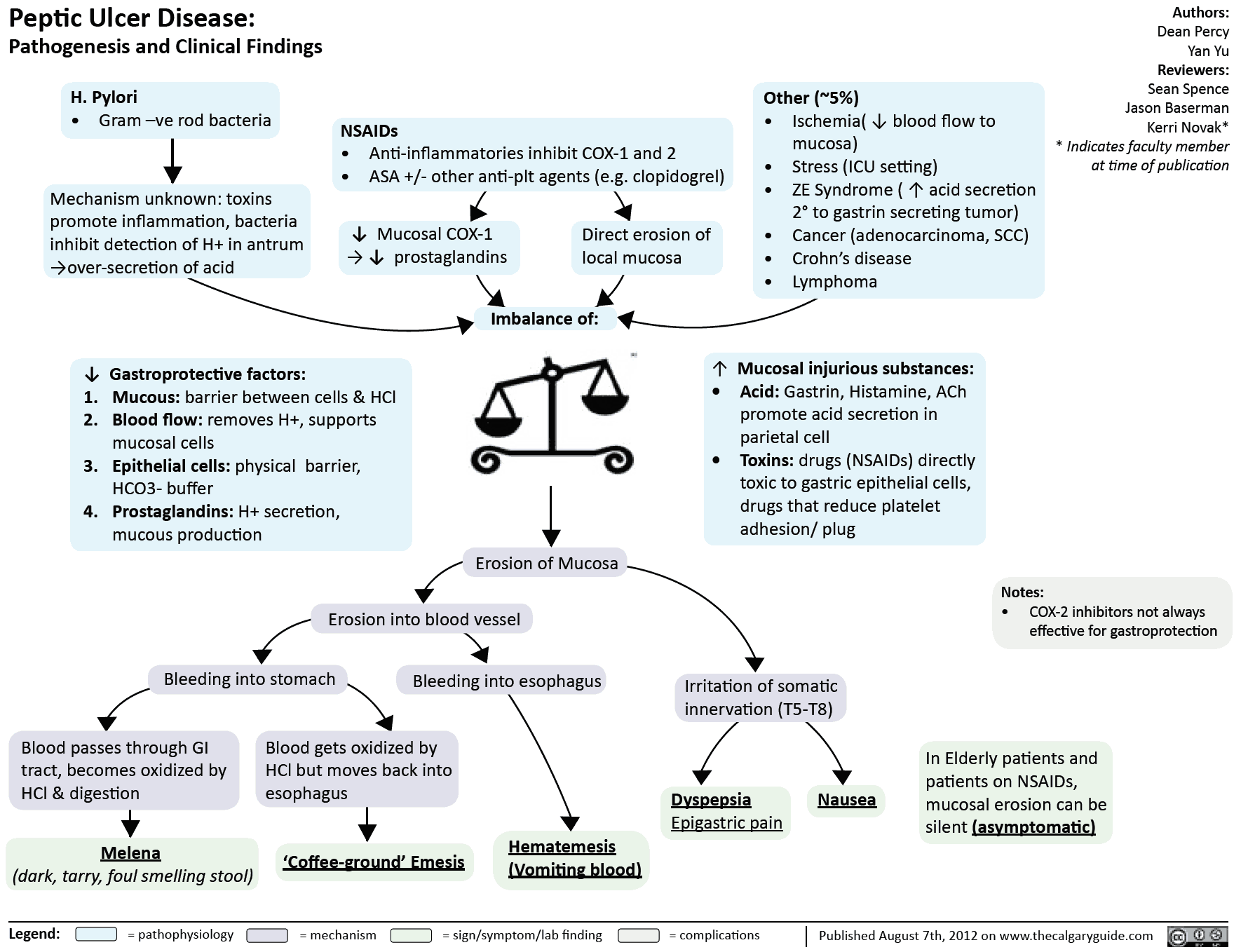

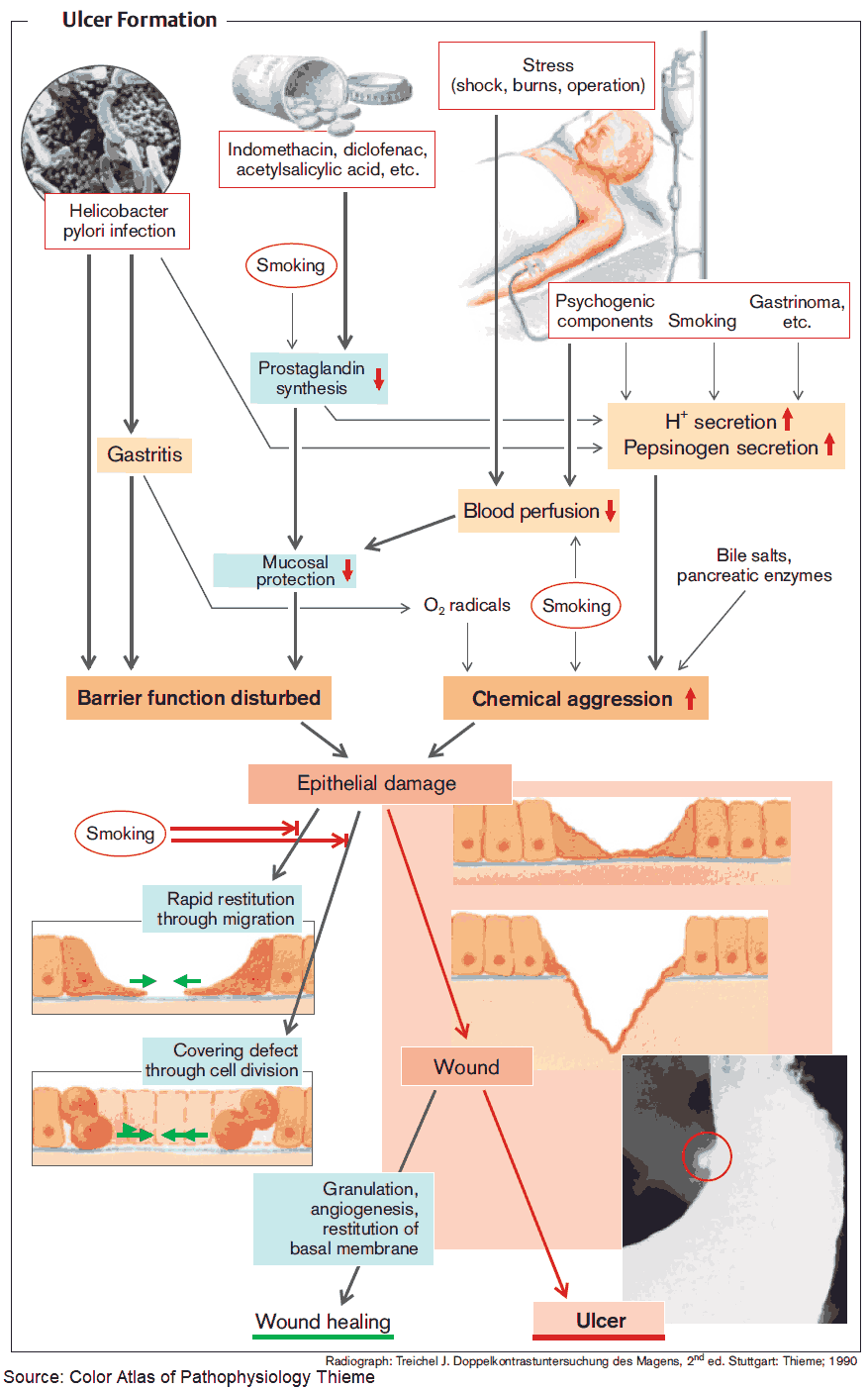

It occurs in up to 15-20% of the population at some time, and is more common in men. The incidence increases with age. Although no cause is usually found, peptic ulceration is associated with gastric hypersecretion and impaired mucosal defences. Helicobacter pylori plays a central role.

Exacerbating factors include:

- stress (Curling’s ulcer)

- smoking

- alcohol

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- steroids

Ulceration is also associated with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type I, and hyperparathyroidism.

Clinical Features of Peptic Ulcer Disease

The history is unreliable for separating duodenal ulcer (DU) from gastric ulcer (GU).

Epigastric pain, often quite localized, is a frequent symptom. The pain may radiate to the back in posterior DU and is episodic, often waking the patient at night, whereas the pain with GU is worse during the day. The pain is relieved with antacids or milk. The pain of DU is often relieved by food, whereas with GU it is precipitated by food.

Other symptoms include nausea and heartburn secondary to acid reflux. Anorexia, vomiting, and weight loss should lead to the suspicion of gastric carcinoma. If there is persistent and severe pain, complications such as perforation or penetration into other organs should be considered.

Examination reveals epigastric tenderness. A mass suggests carcinoma, and a succussion splash suggests pyloric obstruction secondary to scarring.

Peptic Ulcer Disease: Investigations

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) or upper GI endoscopy are the investigations of choice, although a trial of acid suppression may be given to younger patients as carcinoma is rarely present in those under 45 years old.

Patients younger than 45 should have a serologic, fecal antigen or breath test for H. pylori.

All gastric ulcers should be biopsied to exclude malignancy, but DUs are nearly always benign; biopsies should be taken for H. pylori. Most gastric carcinomas are on the greater curve and in the antrum. They may have a rolled edge and a translucent halo around them.

Acid secretion status may be assessed if Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is suspected, before and after stimulation with secretin.

Management of Peptic Ulcer Disease

The patient should be advised to modify exacerbating factors such as smoking, diet, and alcohol. NSAIDs should be stopped if not absolutely necessary.

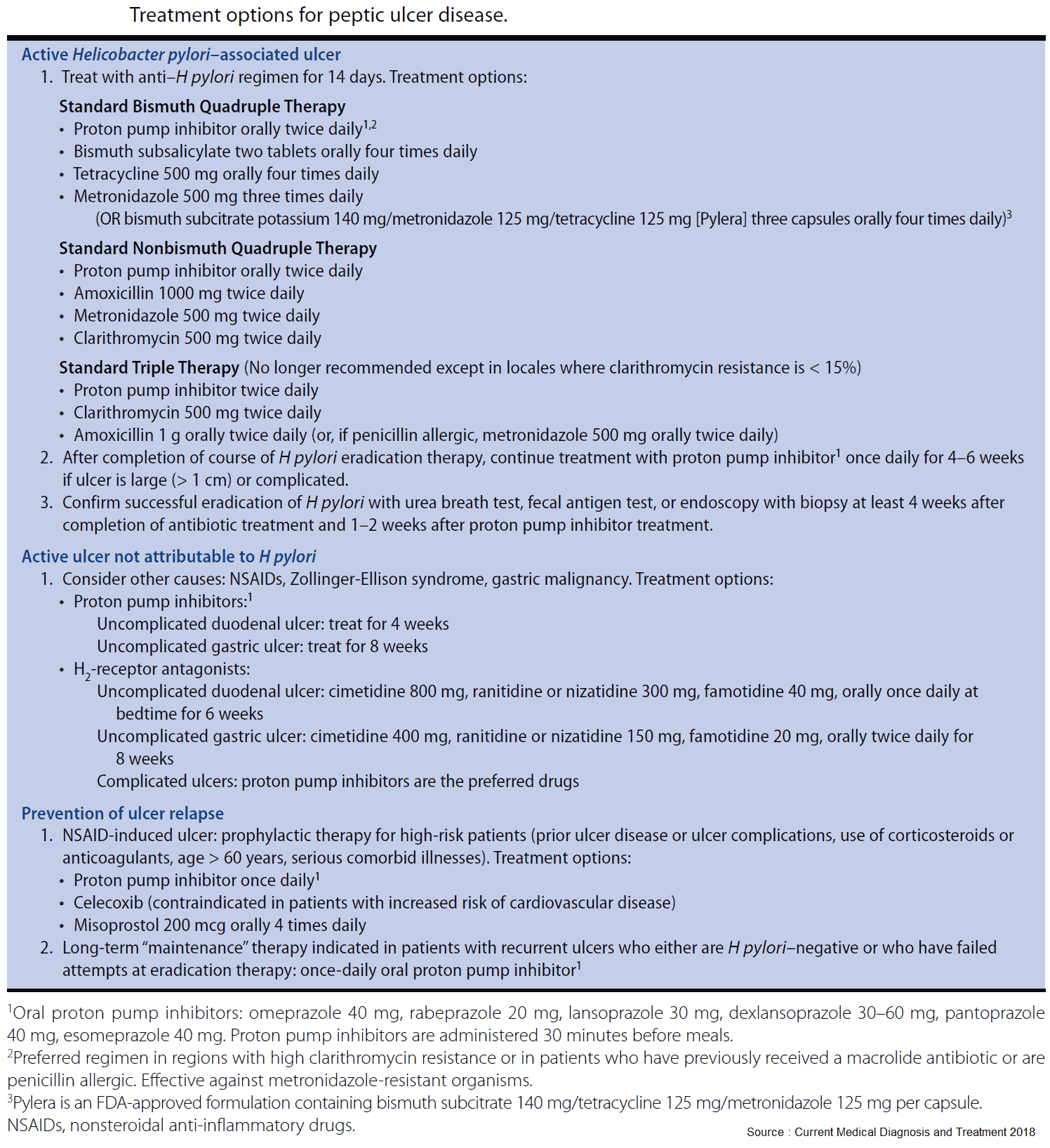

H. pylori should be eradicated because eradication promotes long-term healing of duodenal and gastric ulcers. This is best achieved by acid inhibition combined with antibiotic treatment. A proton pump inhibitor (see below) and clarithromycin, plus either amoxycillin or metronidazole, given twice daily for 2 weeks, produce H. pylori eradication in a large proportion of patients. Treatment failure may reflect poor compliance or antibiotic resistance, and antibiotic-induced colitis is a possible risk.

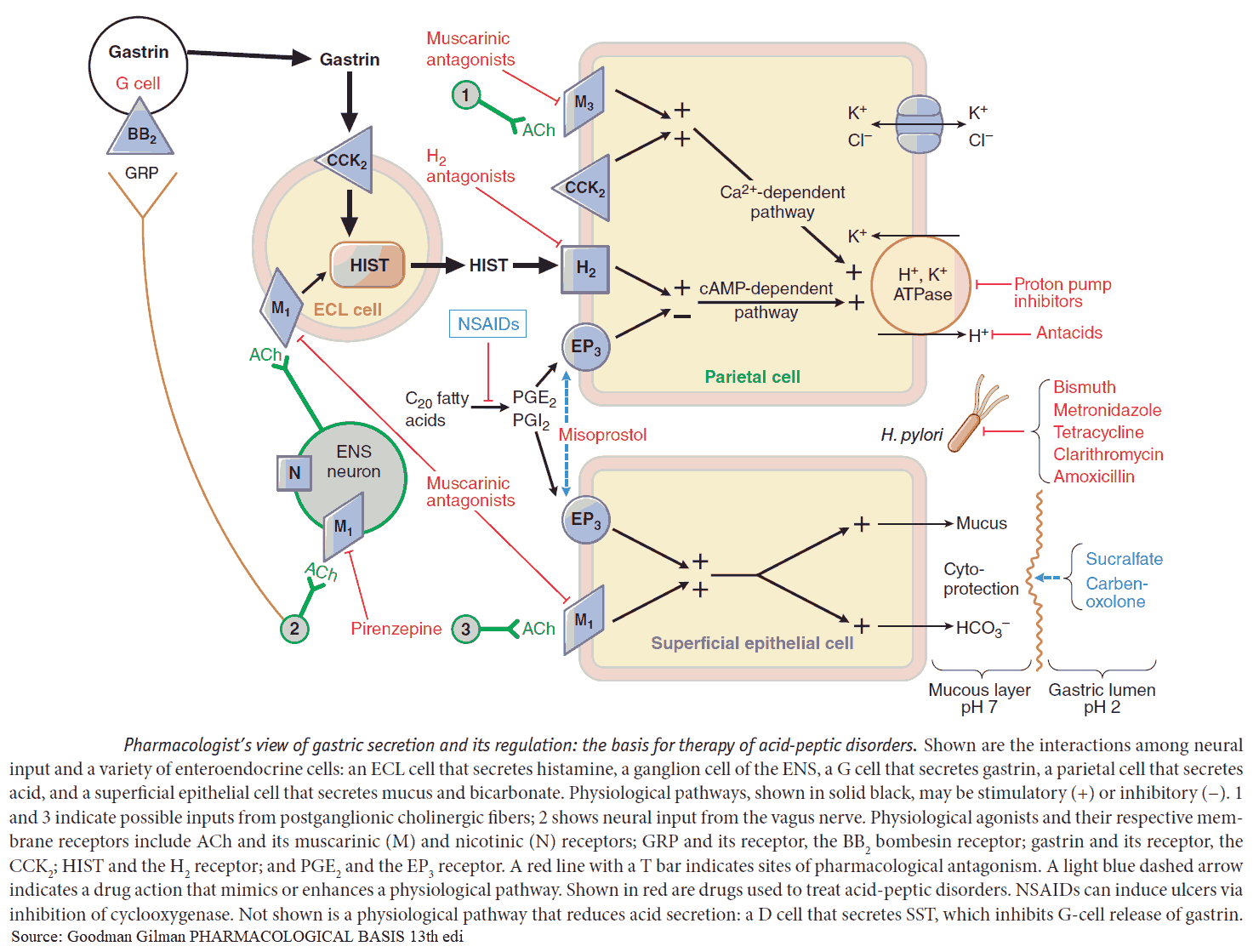

Antacids

Antacids relieve the pain of ulcers but do not necessarily promote healing and are best given when symptoms occur or are expected. Liquid preparations are more effective than tablets. They should preferably not be taken at the same time as other drugs as they may impair their absorption. They may also damage enteric coatings designed to prevent dissolution in the stomach.

Prolonged high doses of calcium-containing antacids can cause hypercalcemia and alkalosis and can precipitate milk-alkali syndrome. Aluminum hydroxide can lower serum phosphate levels and cause constipation, while magnesium carbonate can lead to diarrhea and belching. Some antacids contain a high sodium content and should not be used in patients on salt-restricted diets.

H2-receptor antagonists

These agents heal peptic ulcers by reducing gastric acid output as a result of H2-receptor blockade. Examples include cimetidine, 400 mg 2 times/day, or ranitidine, 150 mg 2 times/day. (Note, however, that because of its involvement with hepatic 450 enzymes and predilection to raise serum creatinine secondary to blockage of creatinine secretion, cimetidine is rarely used.)

Relapse rates are high on stopping treatment, and maintenance treatment may be required, especially in those with frequent severe recurrences and in the elderly. They are generally well tolerated, but cimetidine is occasionally associated with gynecomastia and acute psychosis. It also interacts with warfarin, phenytoin, and theophyllines.

Proton pump inhibitors

These inhibit gastric acid by blocking the hydrogen/potassium adenosine triphosphate enzyme system (the “proton pump”) of the gastric parietal cell. Examples include omeprazole, 20-40 mg q.d., and lansoprazole, 30 mg q.d. High doses may be used in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

PPIs are becoming more and more popular as studies show that they are much more efficacious than H2 blockers. Their popularity has also grown thanks to a generous advertising campaign by various pharmaceutical companies. Recently a PPI became available over the counter. Note, however, that the “new” version of this popular “colored” pill is nothing more than the enantiomer (chemical mirror image) and not a new medication. Side effects include headaches, diarrhea, rashes, pruritus, and dizziness.

Other drugs

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin analog and has antisecretory and protective properties, promoting peptic ulcer healing. It can prevent ulcers secondary to NSAIDs and is useful in patients in whom NSAIDs cannot be withdrawn. The usual dose is 800 μg daily in divided doses. The main side effect is diarrhea.

Sucralfate may act by protecting the mucosa from acid-pepsin attack in peptic ulcers. It is a complex of aluminium hydroxide and sulphated sucrose but has minimal antacid properties.

Tripotassium dicitratobismuthate is a bismuth chelate effective in healing gastric and duodenal ulcers but not on its own in maintaining remission. It may be given in combination with two antibiotics to eradicate H. pylori, but other regimens are preferable.

READ MORE about Drugs for Gastric and Duodenal Ulcers

Surgery

Surgery is usually considered when medical treatment has failed or for complications that include: persistent hemorrhage, perforation and pyloric stenosis

Operations include partial gastrectomy or, now more commonly, highly selective vagotomy and pyloroplasty. Hemorrhage may be controlled endoscopically by injection or diathermy, laser photocoagulation, or heat probe. Perforations are usually oversewn with an omental plug.

Complications of surgery include:

- Recurrent ulceration.

- Abdominal fullness.

- Bilious vomiting.

- Diarrhea.

- Dumping syndrome. This is fainting and sweating after eating, possibly due to food of high osmotic potential being dumped into the jejunum and causing oligemia because of rapid fluid shifts. Late dumping is due to hypoglycemia and occurs 1-3 hours after taking food.

Metabolic complications include:

- Weight loss.

- Malabsorption.

- Bacterial overgrowth (blind loop syndrome).

- Anemia, usually due to iron deficiency following hypochlorhydria and stomach resection.

Complications

The three main complications secondary to peptic ulceration are:

- bleeding

- perforation

- pyloric stenosis

Perforation is more common in DUs than GUs. Pyloric stenosis may also be prepyloric or in the duodenum. It occurs because of edema surrounding the ulcer or from scar formation on healing. The patient often has projectile vomiting with food ingested up to 24 hours previously. There may be visible peristalsis and a succussion splash. Vomiting may lead to dehydration and a metabolic alkalosis. Fluid and electrolyte replacement is needed, as is gastric aspiration with a nasogastric tube. Surgery is indicated if the patient does not settle with conservative management.