Acute pancreatitis is the leading cause of gastrointestinal (GI) related hospitalizations in the United States, accounting for over 280,000 hospitalizations each year.

One-fifth of these cases are considered severe, carrying a mortality rate of around 10% or 25%, depending on whether these cases are sterile or infected, respectively.

Recognizing Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP)

Recognition of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is tricky, as many of the criteria, such as Ranson, Imrie-Glasgow, and APACHE II, are determined 24 to 48 hours after presentation. This renders them unhelpful in the emergency department (ED) time frame.

Meanwhile, the CT severity index/Balthazar score is not available unless CT has been performed—and CT imaging early on in patients with a straightforward diagnosis of pancreatitis is actually discouraged.

Finally, it should be noted that the degree of lipase elevation itself is not helpful in predicting severity of acute pancreatitis.

Early identification and aggressive management of Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP) are linked directly to improved survival, leading to the idea of the “golden hours” of SAP, treating SAP similar to severe sepsis or a severe burn.

Two new scores have been proposed in recent years that are helpful in the ED diagnosis of Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP).

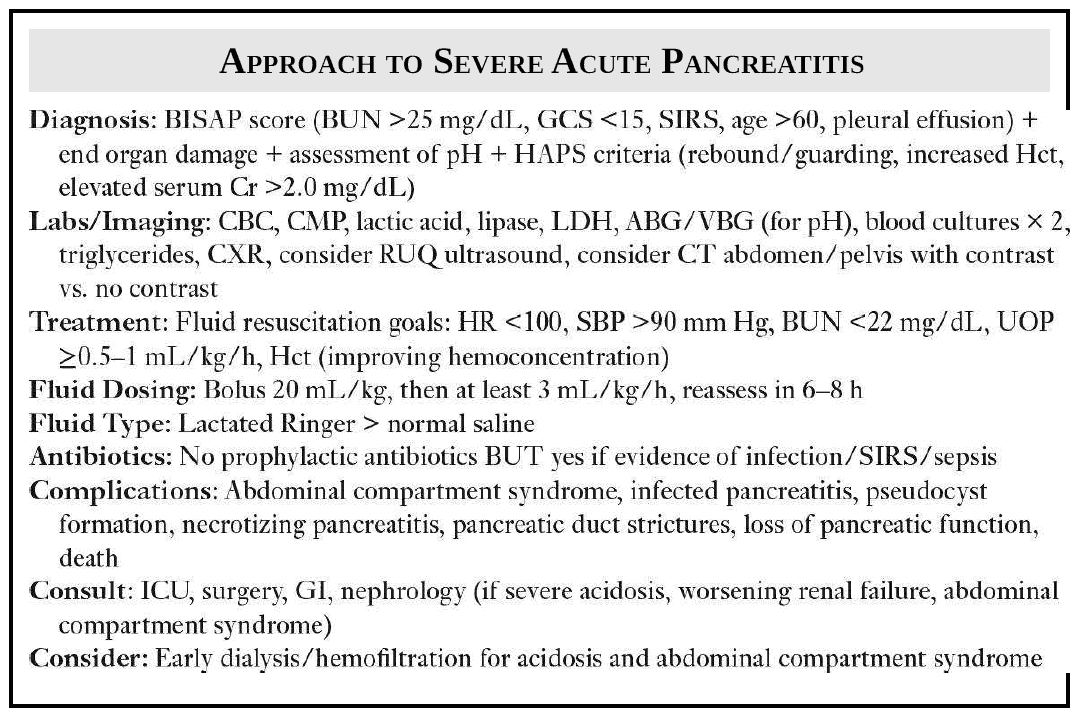

1. Bedside Index of Severity of Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) score

The first is the Bedside Index of Severity of Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) score, which consists of five factors:

- blood urea nitrogen (BUN) >25 mg/dL

- impaired mental status (Glasgow Coma Score <15)

- presence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)

- age >60 years old

- pleural effusion on imaging.

Each variable, if present, is worth 1 point. Scores of 3, 4, and 5 are reflective of in-hospital mortality 474 rates of 8.3%, 19.3%, and 26.7%, respectively.

A BISAP score ≥3 is also associated with an increased risk of developing organ failure, persistent organ failure, and pancreatic necrosis.

2. Harmless Acute Pancreatitis (HAP) Score

A scoring system that excludes Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP) is the harmless acute pancreatitis (HAP) score. This score looks at three factors:

- Hematocrit (Hct)

- Serum creatinine (Cr) >2.0 mg/dL

- Rebound tenderness/guarding on exam

Patients without any of the three are unlikely to develop Severe Acute Pancreatitis (sensitivity of 96%). Independently, Cr > 1.8 mg/dL is a predictor of poor prognosis in SAP.

Using these scoring systems alongside clinical experience, one has a better chance at identifying Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP). Severe acute pancreatitis can be a rapidly progressive disease and thus requires aggressive initial management in the ED even if a patient appears clinically well.

Treating Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP)

Fluid resuscitation and supportive care are the crux of early SAP management.

Common pitfalls include insufficient fluid resuscitation and using the wrong type of fluid.

- An initial bolus of 20 mL/kg followed by 3 mL/kg/h is appropriate with a goal urine output of 0.5 to 1 mL/kg/h, heart rate <100, systolic blood pressure >90, if there are no cardiac or pulmonary contraindications.

- A reassessment of BUN, Cr, lactate, and Hct should be performed in 6 to 8 hours, and at that time, the fluids should be decreased to 2 mL/kg/h if all the parameters are improving.

- Some evidence favors lactated Ringer’s over normal saline, but this is an area of ongoing controversy.

- Prophylactic antibiotics are no longer recommended. However, if the patient has evidence of infection and/or meets SIRS criteria, empiric antibiotics are indicated.

For SAP, ICU admission should be discussed. At a minimum, surgery and GI should be consulted.

RUQ ultrasound should be considered if gallstone pancreatitis is suspected.

A contrast CT of the abdomen/pelvis can help further stage pancreatitis, but a CT is often more useful 48 to 72 hours after the onset of symptoms, after a trial of medical management, to detect surgical complications.

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS) as a Complication of Severe Acute Pancreatitis

As fluid resuscitation continues, serial abdominal exams with measurement of abdominal compartment pressure should be conducted to ensure that abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) does not develop. This is defined as an intra-abdominal compartment pressure of >20 mm Hg associated with new-onset organ failure.

If Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS) develops, initial (medical) management includes:

- Decreasing intestinal volume: nasogastric/orogastric drainage, promotility agents, rectal tubes, and, if necessary, endoscopic decompression

- Decreasing intra-/extravascular fluid: decreasing volume resuscitation and, if volume overloaded, either ultrafiltration or diuretics

- Medical abdominal wall expansion: analgesia and sedation to decrease abdominal muscle tone and, if necessary, neuromuscular blockade

- If these strategies fail, surgical decompression may be indicated. However, new literature considers dialysis/hemofiltration as a less invasive alternative. Early surgery and nephrology consultations will assist with managing this insidious yet deadly complication.

READ MORE about : Know how to Identify Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Key Points

- Early identification and aggressive management of Severe Acute Pancreatitis are linked directly to improved survival.

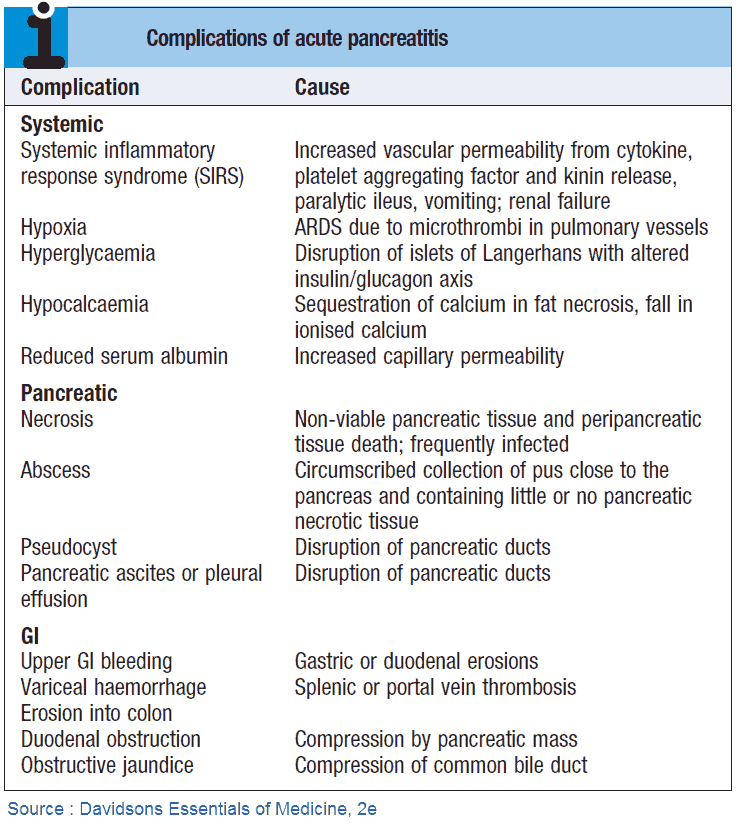

- Patients with Severe Acute Pancreatitis may develop abdominal compartment syndrome, infection, pseudocyst, and other life-threatening complications.

References / Suggested Readings

- Forsmark CE, Gardner TB, eds. Prediction and Management of Severe Acute Pancreatitis. New York: Springer, 2015.

- Lankisch PG, Weber-Dany B, Hebel K et al. The harmless acute pancreatitis score: A clinical algorithm for rapid initial stratification of nonsevere disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(6):702–705.

- Working Group IPA/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13(4 Suppl 2):e1–e15.

- Wu BU, Banks PA. Clinical management of patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2013:144(4);1272–1281.

- Wu BU, Johannes RS, Sun X, et al. The early prediction of mortality in acute pancreatitis: A large population-based study. Gut 2008;57(12):1698–1703.