Table of Contents

Hematemesis is the vomiting of fresh (bright red) or altered (“coffee ground”) blood.

Melena is the production of black, tarry stools and is due to bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract of more than 100 mL of blood.

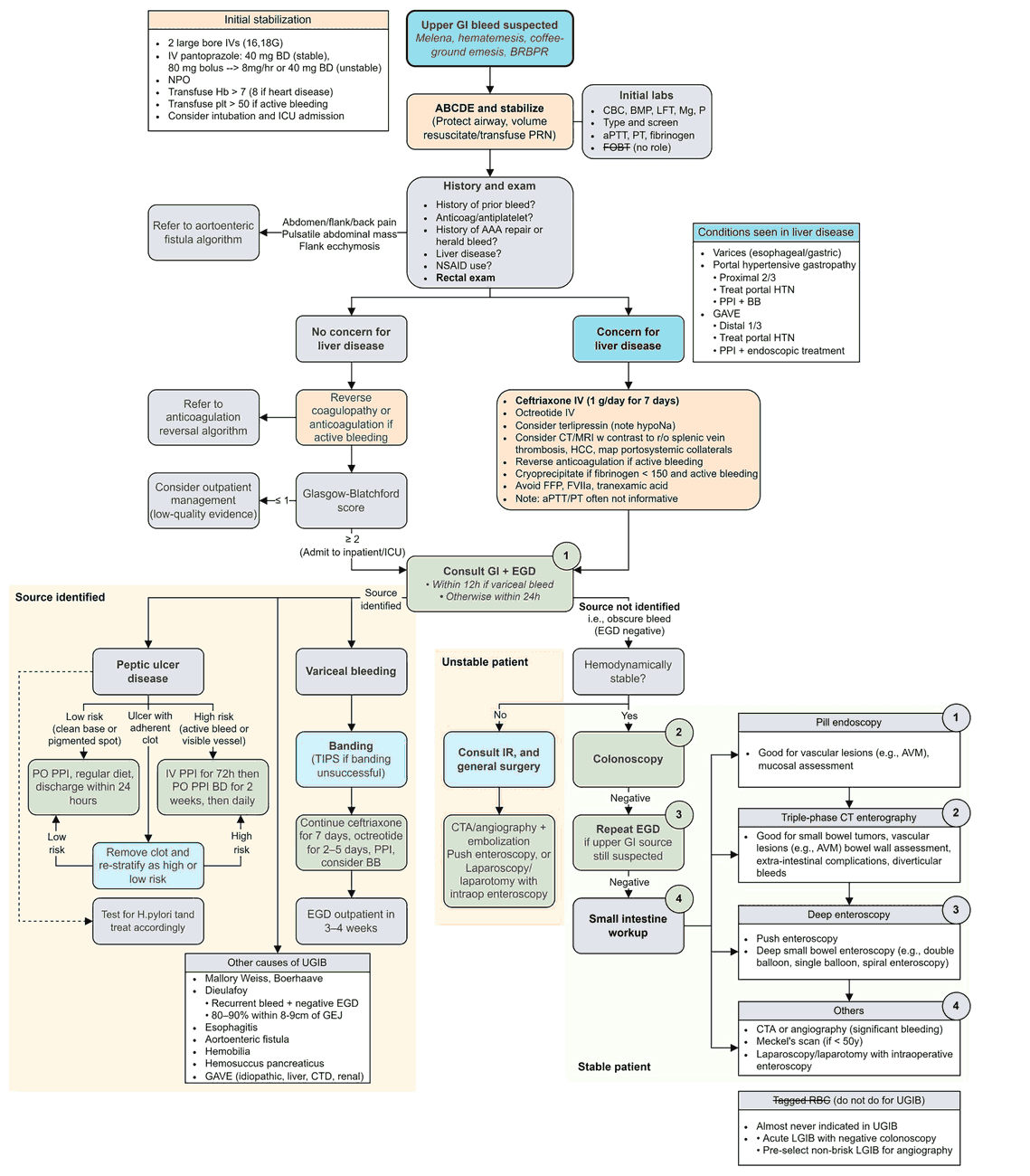

GI bleeding is an emergency, and treatment may need to be initiated before a diagnosis has been made. Always remember that since blood is a cathartic, hematochezia may be caused by an upper GI bleed.

When in doubt place a nasogastric tube and aspirate the contents of the stomach. This will help differentiate between lower and upper GI bleeding in the acute setting.

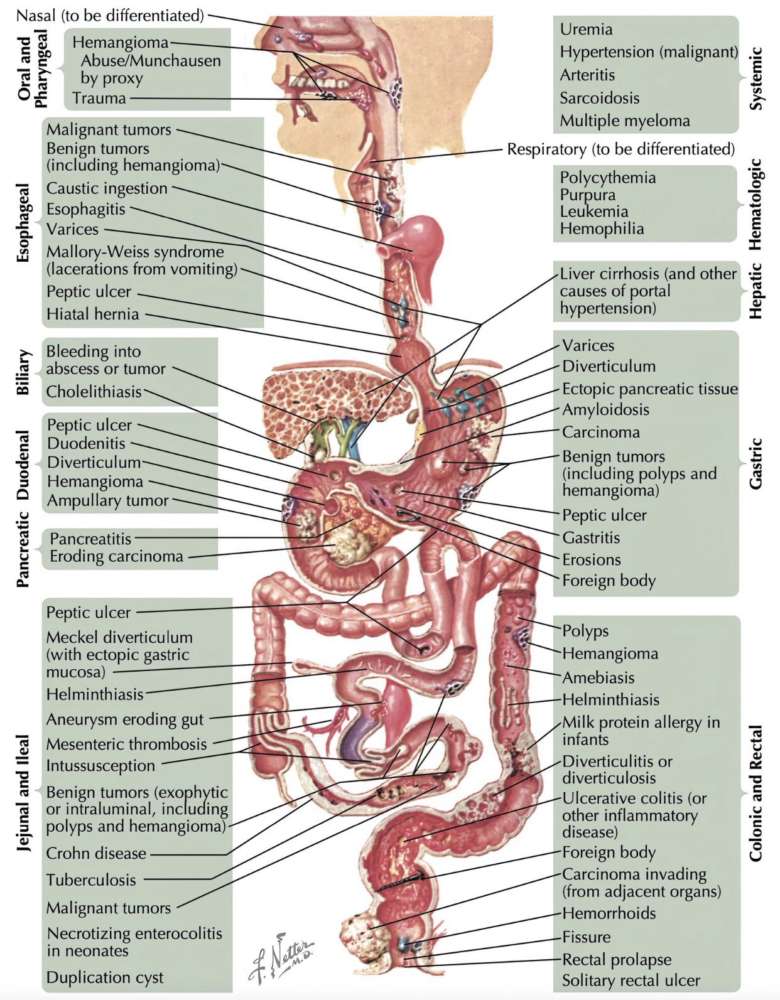

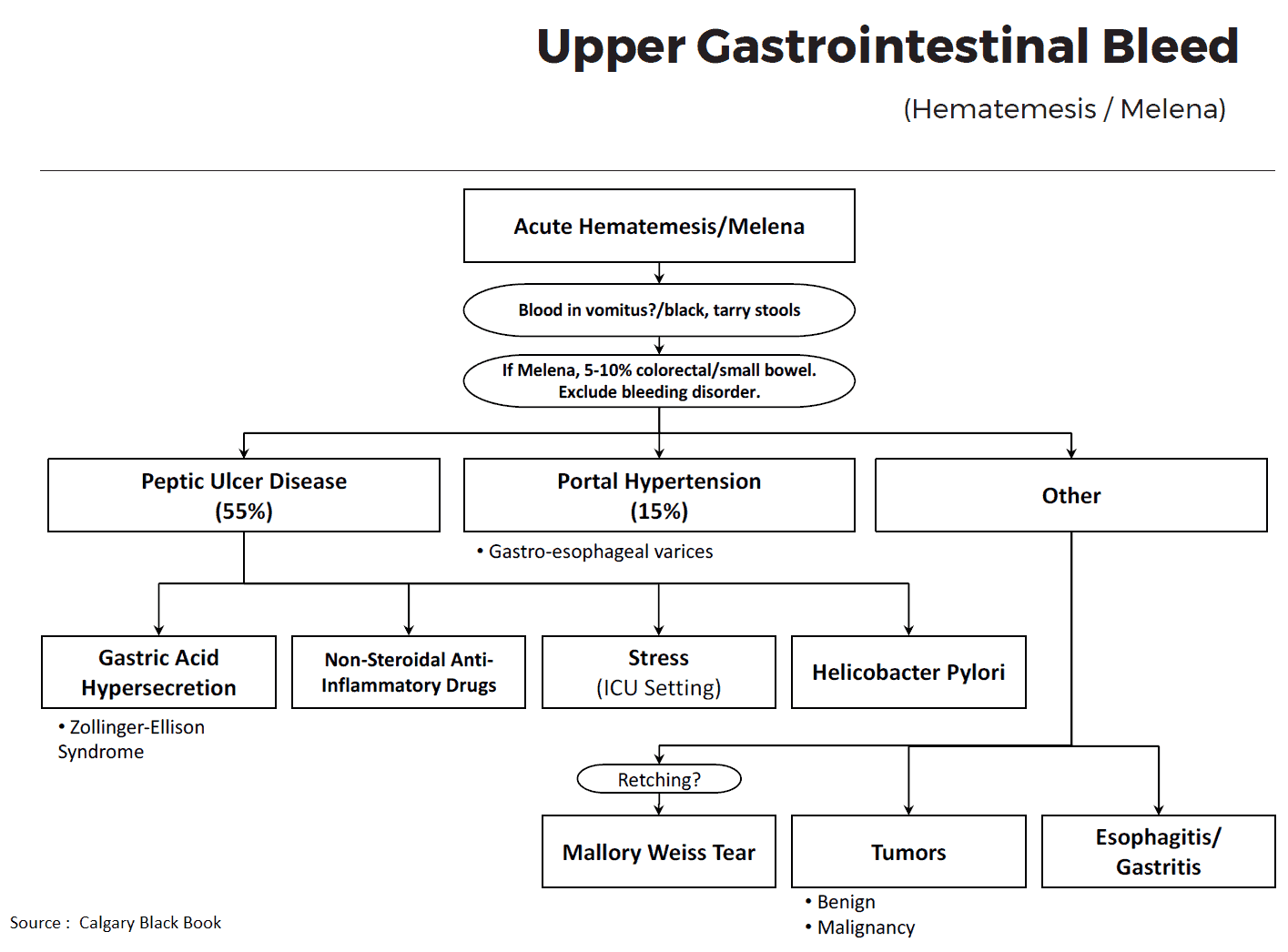

Differential diagnosis of hematemesis, hematochezia, and melena

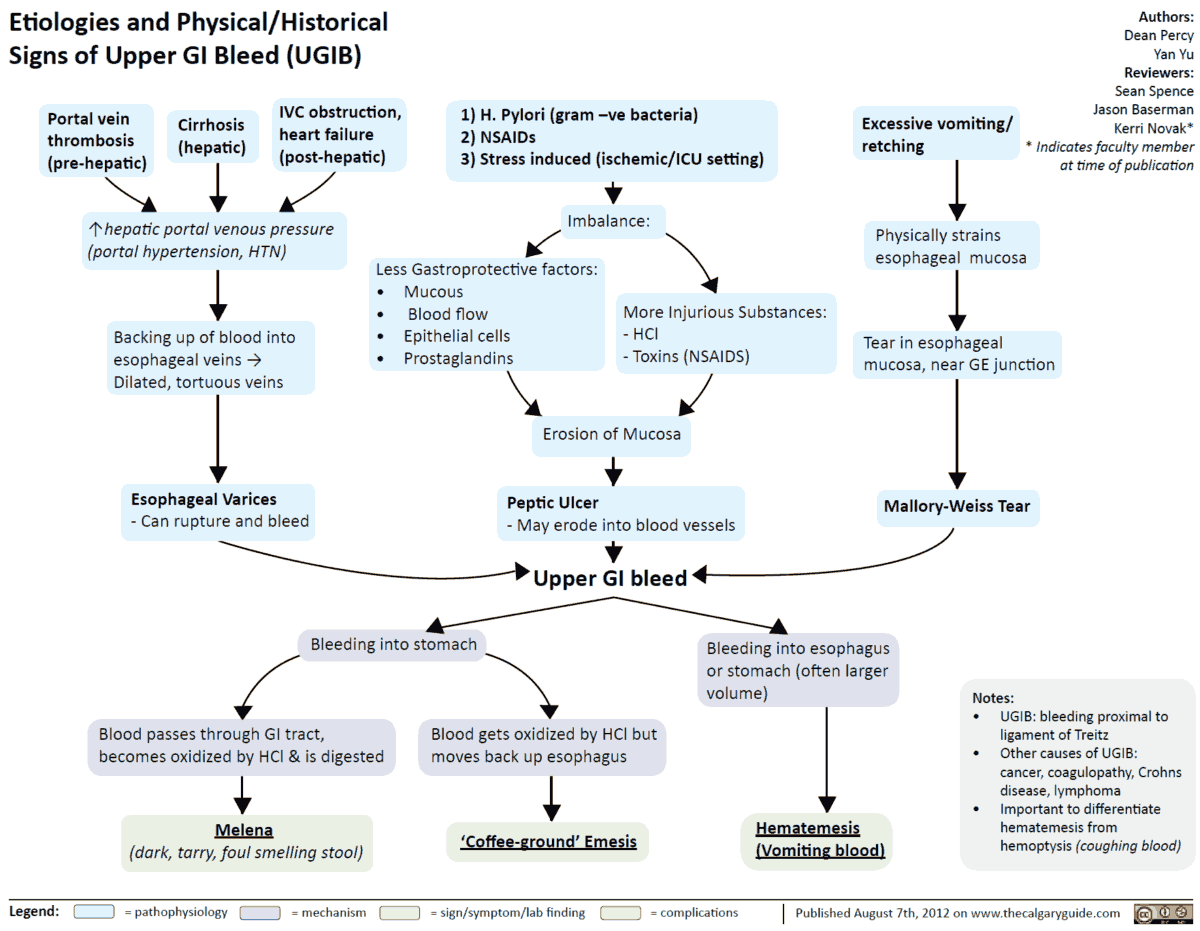

Upper GI bleed (hematemesis/melena) – Causes

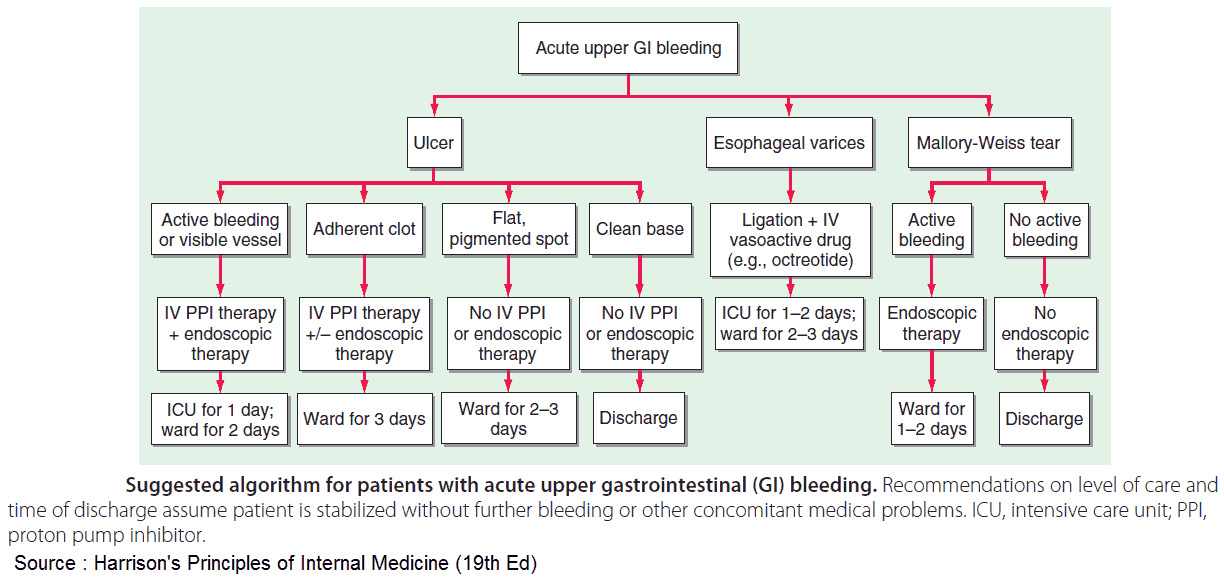

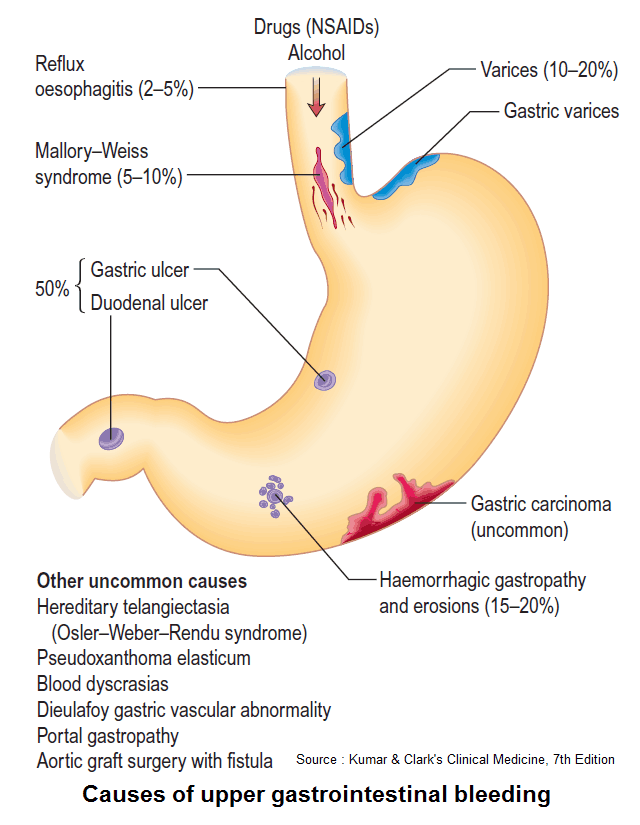

- Peptic ulcer disease: the most common cause, accounting for about half of major upper GI bleeds. The acute mortality rate is about 10%.

- Erosive gastritis: implicated in about 20% of upper GI bleeds, although they are an unusual cause of severe GI bleeding unless associated with other pathology.

- Mallory-Weiss tears: lacerations of the gastroesophageal junction accounting for about 10% of upper GI bleeds. Often due to retching after an alcohol binge.

- Esophagitis/hiatus hernia: secondary to chronic gastroesophageal reflux.

- Ruptured esophageal varices: secondary to portal hypertension, accounting for 10-20% of upper GI bleeds. The acute mortality rate is up to 40%.

- Vascular abnormalities: may cause upper or lower GI bleeding. The most common abnormalities are vascular ectasias or angiodysplasias.

- Dieulafoy’s ulcer: an eroded gastric artery, often with pulsatile bleeding on EGD.

- Boerhave’s syndrome: similar to a Mallory-Weiss tear except that it is a full-thickness esophageal tear. Often the result of persistent vomiting.

- Gastric neoplasms: about 5% of upper GI bleeds.

- Rarer causes include esophageal or stomal ulcers, esophageal tumors, blood dyscrasias, aortoenteric fistula complicating an abdominal aortic graft, pancreatic tumor, pseudoaneurysm.

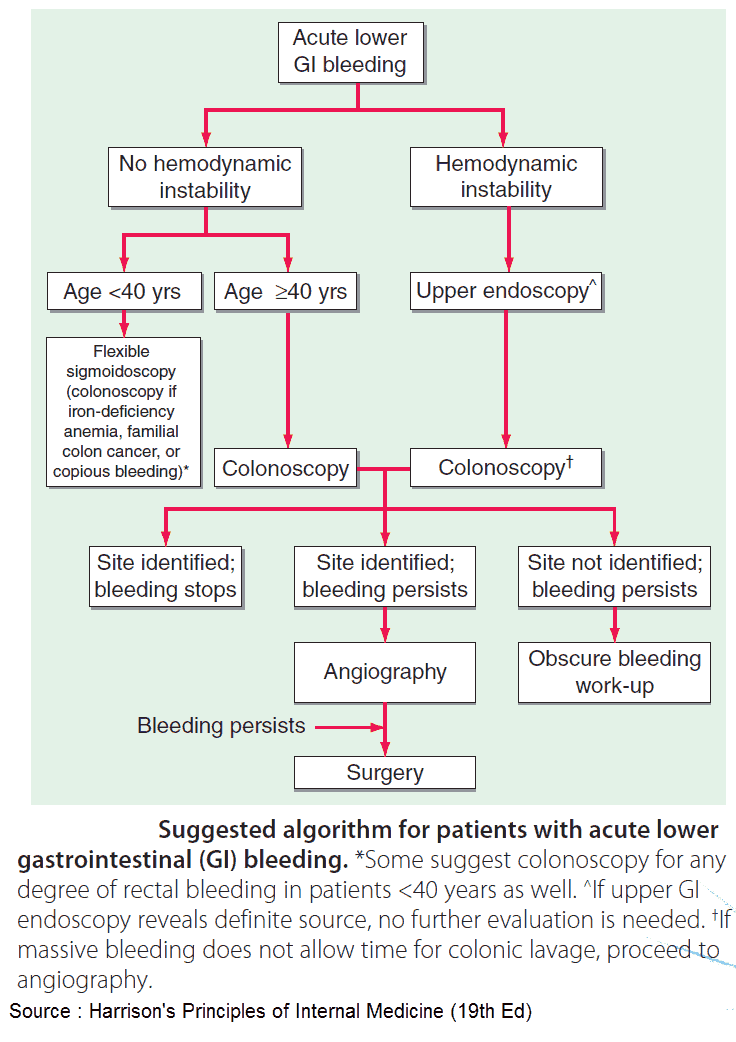

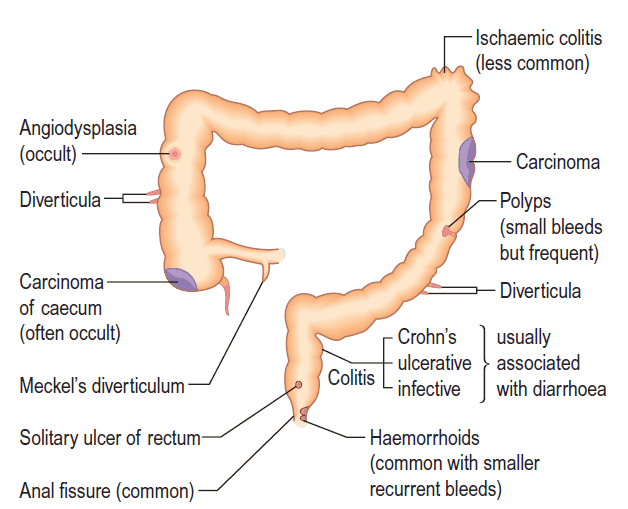

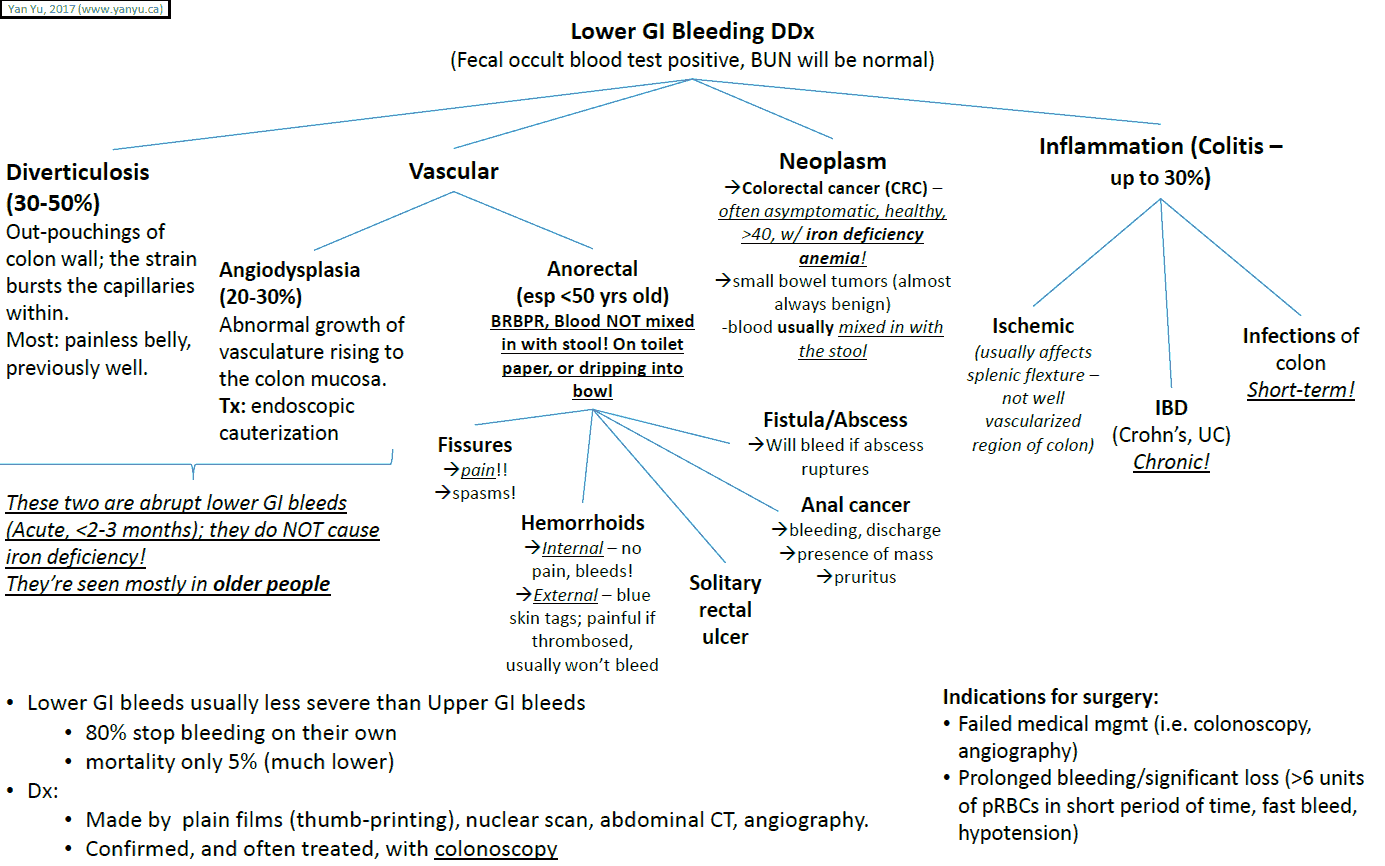

Lower GI bleed (hematochezia/melena) – Causes

- Diverticulosis: diverticuli are small outpouchings, usually of the sigmoid colon, that are prone to bleeding. They are thought to be related to the Western low fiber diet.

- Hemorrhoids: the most common cause of frank drops of blood with defecation. Associated with straining on defecation and a low fiber diet.

- Mesenteric ischemia: emboli or atherosclerosis causes necrosis of a portion of bowel that can then bleed. Usually this is associated with significant pain as well.

- Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs): common causes of acute massive bleeding. AVMs are more common in elderly patients.

- Inflammatory bowel disease: bleeding is more likely with ulcerative colitis, in which bloody diarrhea is common.

- Radiation colitis: the GI epithelium is highly sensitive to radiation, given its frequent regeneration, and can slough and bleed.

- Colonic neoplasm/polyp: often a common cause of occult bleeding, although it can present with frank blood as well. More common in older patients or patients with a family history of polyps and cancer.

History in the patient with hematemesis, hematochezia, and melena

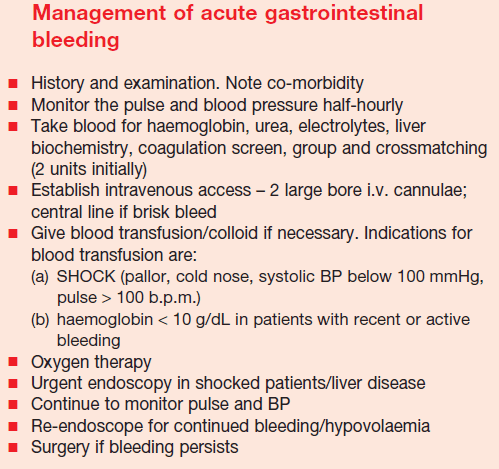

The history may have to be taken after initial resuscitation procedures (i.e., placement of two large-bore IV lines, NG tube, Foley catheter, and blood typing and screen). It is important to determine whether the blood has been vomited or coughed.

In cases of difficulty, the presence of food mixed with the blood or an acid pH is suggestive of hematemesis, although the vomitus may not be acidic in patients with carcinoma of the stomach. Hematemesis may be due to blood swallowed from the nasopharynx or mouth.

You must ask about the following:

- Nonspecific symptoms of GI blood loss: faintness, weakness, dizziness, sweating, palpitations, dyspnea, pallor, collapse. These symptoms may precede the actual hematemesis/melena. Also ask about the time frame of these symptoms. If the patient has fatigue and pallor, are they acute or chronic?

- Weight loss and anorexia: carcinoma.

- Current drugs: aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and excessive alcohol are suggestive of gastric erosions; iron therapy causes black stools, but this is not melena. Clopidogrel and warfarin are also associated with GI bleeds.

- Symptoms of chronic blood loss: suggests gastric carcinoma if associated with anorexia and weight loss.

- Heartburn: esophagitis.

- Intermittent epigastric pain relieved with antacids: peptic ulceration.

- Sudden severe abdominal pain: perforation.

- Dysphagia or odynophagia (pain on swallowing): esophageal carcinoma.

- Chronic excessive alcohol intake: esophageal varices.

- Inquiry into the causes of liver failure: esophageal varices.

- Retching, especially after an alcohol binge: Mallory-Weiss tear.

- Family history: inherited bleeding disorders.

- A past history of GI bleeds and their cause.

Examining the patient with hematemesis, hematochezia, and melena

Step back from the patient for a few seconds. Does the patient look well or pale and clammy? An initial common-sense impression affects the immediacy of subsequent management.

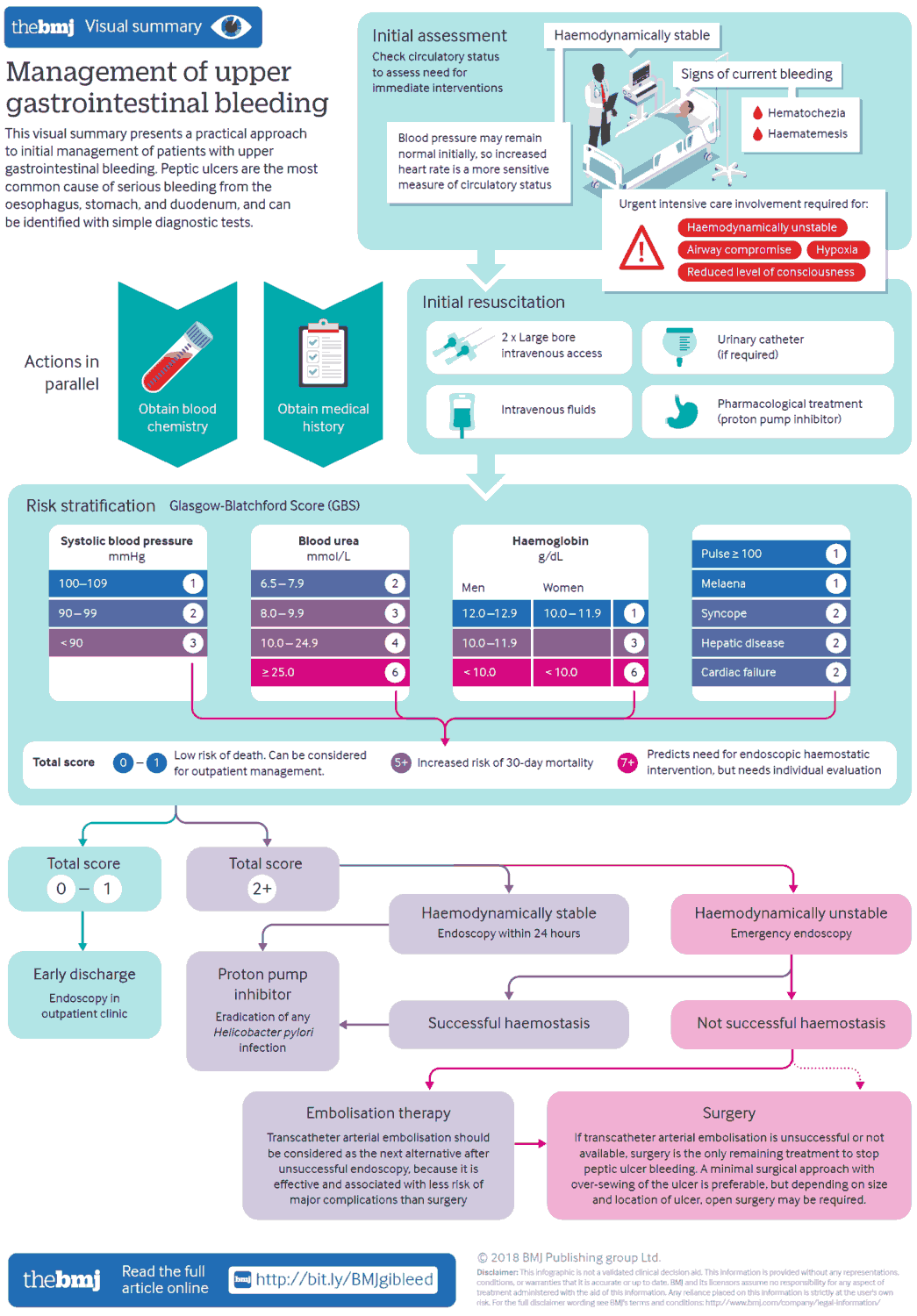

Remember: Vital signs are vital, and the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) should be attended to first. Tachycardia, low blood pressure, or orthostastic blood pressure often indicates a patient who needs immediate attention. In any patient with a suspected GI bleed, two large-bore IV lines should be placed and input/output should be monitored.

If hemoptysis is suspected, a full respiratory examination should be carried out.

General Examination

- Anemia: mucous membranes. If clinically anemic, this may indicate chronic blood loss.

- Jaundice: may indicate portal hypertension.

- Clubbing of fingers: inflammatory bowel disease, cirrhosis.

- Lymphadenopathy: especially Virchow’s node (left supraclavicular lymph node), which is associated with gastric carcinoma (Troisier’s sign).

- Pulse: tachycardia can be the first warning of a large GI bleed and may precede a blood pressure fall. A young and healthy patient may lose more than 500 mL of blood before a rise in heart rate or fall in blood pressure occurs.

- Blood pressure: if hypotensive, intravenous fluids should be given. The pulse and blood pressure measurements should be repeated frequently to monitor hemodynaimc trends.

- Skin: bruises, purpura (bleeding disorders); telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease [hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia-autosomal dominant]); neurofibromata.

- Mouth: pharyngeal lesions; pigmented macules (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome).

- Cachexia.

Specific Examination

- A rigid abdomen suggests perforation.

- Epigastric tenderness suggests peptic ulcer disease, esophagitis, hiatus hernia, or gastric carcinoma.

- Epigastric mass: gastric carcinoma.

- If malignancy is suspected, examine for metastases.

- Signs of chronic liver failure including those suggesting specific diagnoses: xanthelasmata in primary biliary cirrhosis; slate-gray pigmentation in hemochromatosis; Kayser-Fleischer rings in Wilson’s disease, elevated prothrombin time and Dupuytren’s contracture in chronic alcohol abuse.

- A rectal examination is essential. This will confirm the presence of melena, which may be present despite hemodynamic stability.

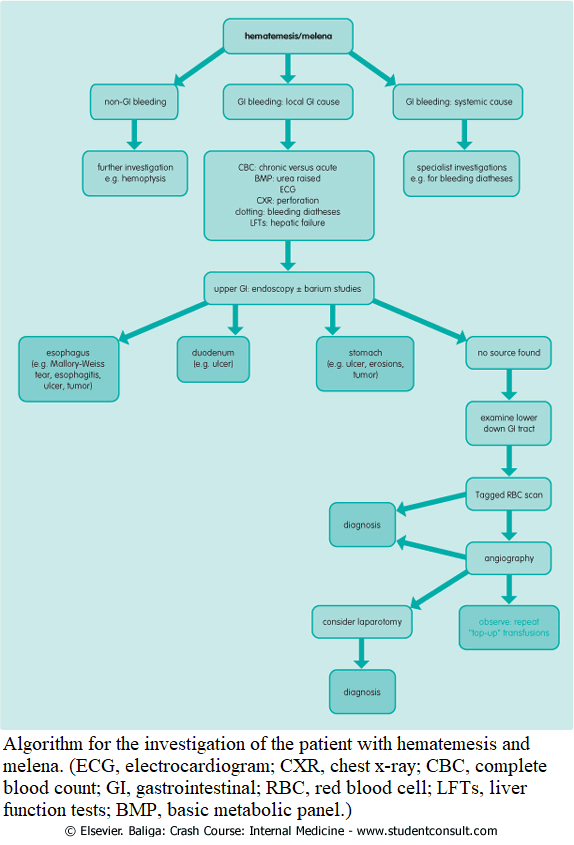

Investigating the patient with hematemesis, hematochezia, and melena

The following investigations should be carried out:

- A complete blood count should be performed as part of the investigation.

- The hemoglobin may be normal in the acute phase, despite a large GI bleed, as it takes some hours for hemodilution to occur.

- A low hemoglobin on initial presentation suggests chronic blood loss

- White cell count may be raised after a GI bleed.

- Platelet count may be reduced after an acute bleed, or increased after chronic blood loss.

- A very low platelet count should raise suspicion of a bleeding diathesis.

- Type and cross even if there is only a small GI bleed and the patient is hemodynamically stable. Blood should be cross-matched for more significant bleeding.

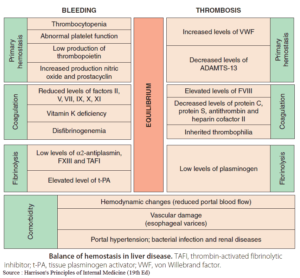

- Coagulation studies should also be performed since the prothrombin time is raised in liver disease. More specific investigations may be indicated (e.g., in patients with hemophilia or von Willebrand’s disease).

- Urea is raised due to the absorption of protein when blood reaches the small bowel.

- Elevated blood urea with normal serum creatinine suggests gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Chronic renal failure can be associated with GI bleeding.

- On erect chest x-ray, the presence of gas under the right hemidiaphragm indicates perforation.

Further investigations are done to confirm the site of the bleeding and to make a definitive diagnosis:

Endoscopy

Endoscopy allows direct visualization of the pathology and can identify the source of the bleeding. It will determine the most appropriate form of medical therapy.

The risk of rebleeding may be estimated; for example, Mallory-Weiss tears or erosive gastritis have a low risk of rebleeding with appropriate management, whereas esophageal varices have a much higher risk of rebleeding.

Treatment may be given endoscopically (e.g., banding of the varices, injection of a sclerosant into a bleeding varix, or cautery of a bleeding vessel).

New treatments for variceal bleeding include octreotide and vasopressin. Remember, however, that octreotide must be given with nitroglycerin because its vasoconstricting effects occur in the coronary arteries as well as in the portal and splenic beds.

Barium Examinations

Barium examinations are becoming rarer as endoscopy is becoming more widely available, although they may be useful when endoscopy is contraindicated (e.g., in patients with an unstable cervical spine).

Abdominal ultrasound

Abdominal ultrasound should be performed to determine whether liver cirrhosis is present or to look for metastases if carcinoma is suspected. Abdominal computed tomography scanning may be helpful if a mass is present.

Tagged red blood cell scans

Tagged red blood cell scans require active bleeding to be present. They may be useful for continued bleeding despite a thorough search of the GI tract and help the surgeon if resection of the bleeding segment is considered.

Mesenteric angiography

Mesenteric angiography again requires active bleeding to localize the source. It can also be used to visualize the portal venous system.