Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is a rare blood disorder. It causes the body’s immune system to produce antibodies to attack its own red blood cells. This leads to anemia, shortness of breath, fatigue, and more.

An ASH Publications study states that the prevalence of AIHA varied across different databases analyzed. Point prevalence per 1,000,000 ranged from about 210 in Medicare FFS to 160 in Optum and 50 in MORE2. Incidence followed the same pattern, with Medicare FFS showing the highest rates and MORE2 the lowest.

Even though standardized values differed, age-stratified results aligned more closely. It suggested that population differences across databases shaped the overall estimates.

Since it is a rare condition, it can unfold in ways that make early recognition difficult, especially when patients demonstrate subtle or inconsistent signs. A person may arrive with vague tiredness, mild skin discoloration, or unexplained changes in laboratory values that do not point clearly toward red cell destruction.

These situations create an environment where traditional diagnostic shortcuts fall short, encouraging clinicians to stay alert to small discrepancies. Early impressions often feel incomplete, and the picture becomes clearer only after multiple encounters, repeated testing, and a willingness to reconsider the initial assessment.

Recognizing Atypical Patterns

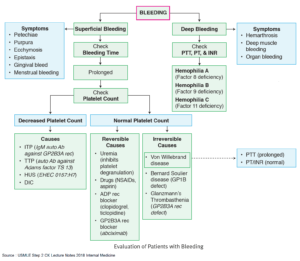

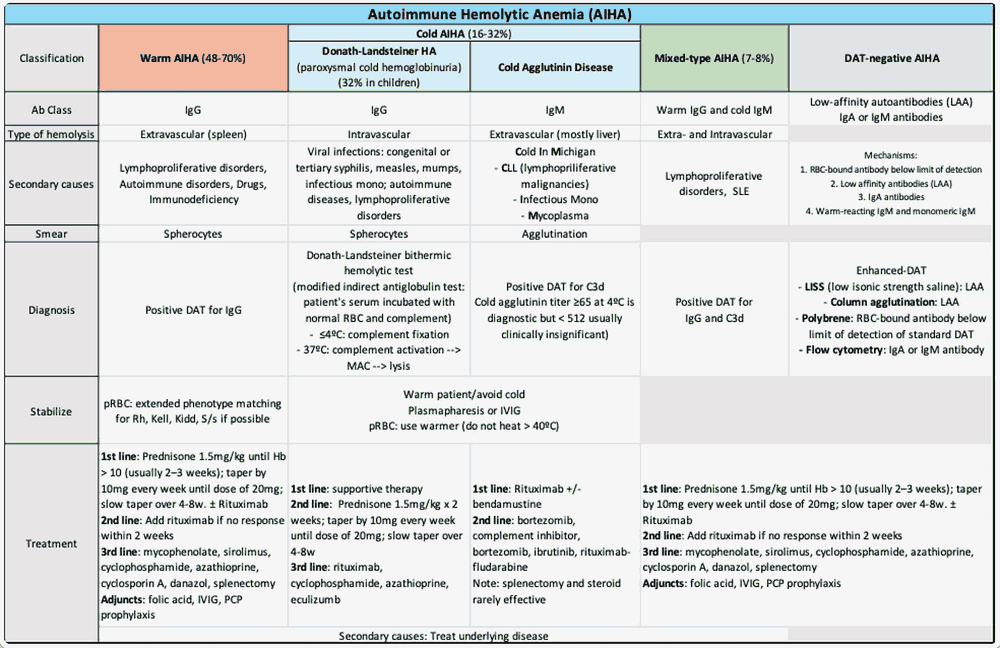

AIHA is broadly divided into warm and cold forms based on antibody type and thermal activity. An NCBI study notes that diagnoses heavily rely on the direct antiglobulin test. It distinguishes patterns through specific IgG or C3d/IgM findings. However, there are also rare forms like mixed, atypical (IgA or warm IgM driven), and DAT-negative. All of these can together make diagnosing atypical AIHA challenging.

A patient may exhibit mild anemia with normal bilirubin levels or slight reticulocytosis despite clear symptoms of weakness. These mismatches encourage clinicians to broaden their thinking and revisit key diagnostic steps.

Some clinicians are now exploring emerging therapeutic frameworks like bispecific antibody engineering while discussing diagnostic possibilities. With an advanced bi-specific antibody platform, researchers can create lab-engineered molecules that bind to two different antigens simultaneously.

According to Alloy Therapeutics, an advanced platform can help throughout the bispecific antibody generation process. It can help rank order bispecific candidates for better specificity and functional activity.

This perspective encourages a more thorough evaluation of antibody behavior and supports closer attention to unusual serologic results. Subsequent analysis usually involves a careful comparison of direct antiglobulin test findings over time.

A patient with intermittent positivity or fluctuating immunoglobulin patterns may prompt revisiting earlier labs and correlating them with physical changes. Repeated assessments frequently reveal subtle trends that were not obvious at presentation, allowing the clinician to refine the diagnostic direction.

Differentiating Underlying Triggers

Atypical cases often stem from conditions that mask classic signs. Mild infections, subclinical autoimmune activity, or medication effects can distort laboratory expectations. It prompts clinicians to follow a more layered review of the patient’s history.

A Cureus study presented a case that masked hemolytic anemia in the form of atypical pneumonia. The 23-year-old female patient was brought to the emergency room with a history of Mycoplasma pneumonia. She was also treated for an upper respiratory tract infection with cefdinir. All this complex history made it challenging to determine AIHA.

Her evaluation showed clear signs of hemolysis and a DAT positive only for complement. This came along with incidental lung infiltrates, negative infectious and autoimmune testing, and a low cold agglutinin titer. She improved significantly with doxycycline and supportive care, including transfusions, and maintained stable hemoglobin without further hemolysis at follow-up.

The case underscores the need to consider secondary forms in patients with cold-related symptoms or unexplained hemolysis. Primary cases may demand more intensive options such as rituximab or sutilumab.

Gradual evaluation of organ involvement and longitudinal observation of hemoglobin shifts can expose hidden patterns that support or refute initial suspicions. These steps help distinguish immune-driven destruction from alternative causes such as mechanical hemolysis or metabolic disturbances.

Serologic profiles sometimes resemble mixed mechanisms, and this overlap can complicate interpretation. Reviewing timelines of symptom progression and identifying subtle external triggers helps clarify whether the anemia reflects a transient response or an evolving condition. Clinicians often rely on repeated testing spaced over several days to capture these transitions more accurately.

Interpreting Diagnostic Outcomes

Once early confusion begins to resolve, the focus shifts to confirming whether the hemolysis truly stems from immune activity. Attention to thermal amplitude patterns, antibody specificity, and complement involvement strengthens the diagnostic picture. Persistent mild abnormalities can still signal a meaningful immune process, particularly in patients with coexisting inflammatory disorders.

The following tests can be useful in diagnosing AIHA:

- Complete blood count

- Haptoglobin

- Lactate dehydrogenase

- Reticulocyte count

- Bilirubin

- Direct antiglobulin test

- Indirect antiglobulin test

- Peripheral smear

- Donath-Landsteiner antibody, etc.

Results of these tests can help confirm pathophysiology outcomes, such as warm AIHA, cold agglutinin disease (CAD), paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria, mixed AIHA, and more.

Cases that produce inconsistent results may require advanced consultation or extended laboratory support. Specialized centers can analyze complex antibodies or evaluate unusual binding behaviors that smaller laboratories cannot fully characterize. These insights can guide future monitoring and help clinicians determine whether the patient is at risk for sudden deterioration.

Further examination often involves revisiting blood film patterns with greater attention to subtle changes in cell morphology. Mild spherocytosis or irregular shapes may appear intermittently rather than consistently, which can complicate interpretation.

Gradual shifts in these features across several samples help reinforce or challenge earlier assumptions about immune involvement. Observing such transitions supports a deeper appreciation of how the condition behaves over time, especially in patients who present with minimal symptoms.

Considering Coexisting Immune Disorders

Some individuals experience overlapping autoimmune tendencies that blur diagnostic boundaries. Symptoms attributed to one disorder may mask early indications of hemolysis, causing a delay in recognition.

A closer look at joint symptoms, skin findings, or fluctuating inflammatory markers can reveal patterns suggesting a broader immune process. These clues help clinicians refine their understanding of where the hemolytic picture fits within the patient’s overall health.

There are many examples of such coexisting autoimmune disorders that can make diagnosis challenging. A Wiley Online Library study highlighted a case where a patient was suffering from acute myeloid leukemia and AIHA. The simultaneous occurrence of both these conditions is exceedingly rare. It has a prevalence rate of less than 1%. This makes the dual diagnosis challenging.

Similarly, a Frontiers journal study highlights a case of a 53-year-old man with the unusual combination of CAD and acquired hemophilia A. It was marked by recurrent bleeding symptoms, cold-induced acrocyanosis, severe anemia, prolonged aPTT, a measurable inhibitor, and a high cold agglutinin titer.

Standard immunosuppression with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide proved ineffective and was followed by clinical decline and infection. A course of rituximab led to parallel resolution of both the coagulation defect and the hemolytic process.

Atypical presentations of autoimmune hemolytic anemia challenge clinicians to evaluate data from multiple angles and reconsider early impressions. Careful observation, repeated assessments, and thoughtful interpretation allow a clearer understanding to emerge despite initially confusing patterns.

A structured approach ensures that subtle signs are not dismissed and that patients receive diagnostic clarity even when traditional indicators fail to provide straightforward guidance.

This article is a guest contribution submitted by a professional healthcare writer and reviewed for accuracy.