Table of Contents

Epidemiology

Between 120 and 140 per 1000,000 will develop urinary stones each year with a male/female ratio of 3:1. A number of known factors of influence to the development of stones are discussed bellow.

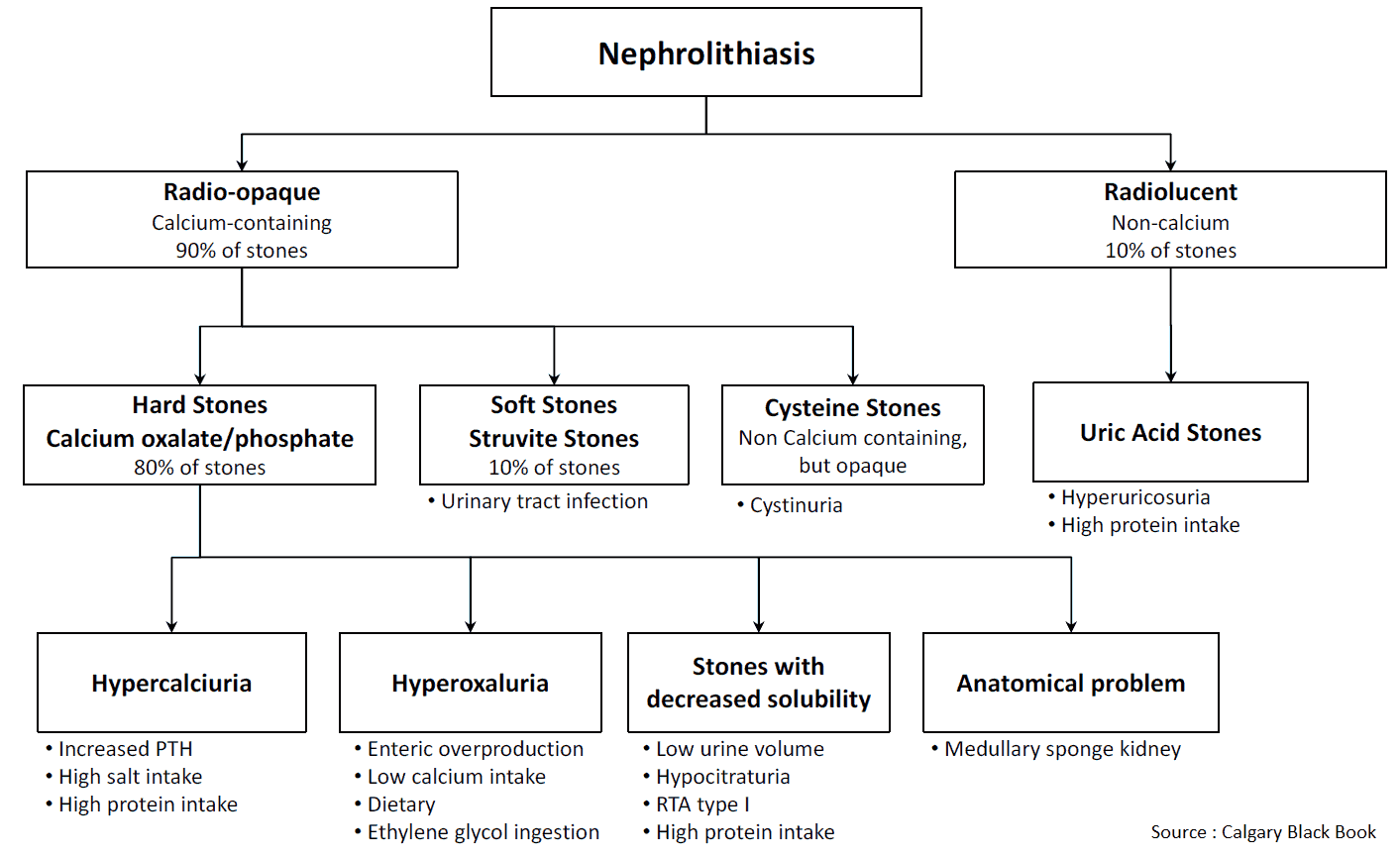

Classification of Kidney and Urinary Stones

Correct classification of stones is important since it will impact treatment decisions and outcome. Urinary stones can be classified according to the following aspects: stone size, stone location, X-ray characteristics of stone, aetiology of stone formation, stone composition (mineralogy), and risk group for recurrent stone formation.

X-ray Characteristics of Kidney and Urinary Stones

| Radiopaque | Poor radiopaque | Radiolucent |

| Calcium oxalate dihydrate | Magnesium ammonium phosphate | Uric acid |

| Calcium oxalate monohydrate | Apatite | Ammonium urate |

| Calcium phosphates | Cystine | Xanthine |

| 2,8-dihydroxyadenine | ||

| ‘Drug-stones’ |

Kidney Stones classified according to their aetiology

| Noninfection stones | Infection stones | Genetic stones | Drug stones |

| Calcium oxalates | Magnesiumammoniumphosphate | Cystine | Indinavir |

| Calcium phospha es | Apatite | Xanthine | |

| Uric acid | Ammonium urate | 2,8-dihydroxyadenine |

Kidney Stones classified by their composition

| Chemical composition | Mineral |

| Calcium oxalate monohydrate | whewellite |

| Calcium-oxalate-dihydrate | wheddelite |

| Uric acid dihydrate | uricite |

| Ammonium urate | |

| Magnesium ammonium phosphate | struvite |

| Carbonate apatite (phosphate) | dahllite |

| Calcium hydrogenphosphate | brushite |

| Cystine | |

| Xanthine | |

| 2,8-dihydroxyadenine | |

| ‘Drug stones’ | |

| unknown composition. |

Risk Groups for Kidney Stone Formation

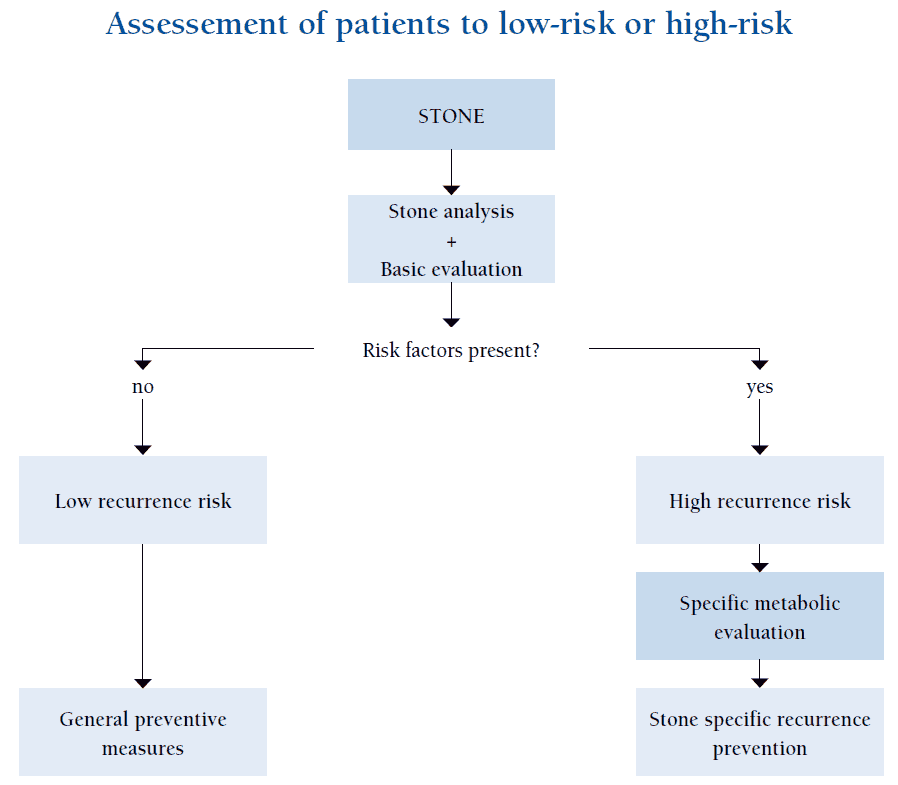

The risk status of a stone former is of particular interest as it defines both probability of recurrence or (re)growth of stones and is imperative for pharmacological treatment.

High Risk Kidney Stone Formers

| General factors for Kidney stone formation |

| Early onset of urolithiasis in life (especially children and teenagers) |

| Familial stone formation |

| Brushite containing stones (calcium hydrogen phosphate; CaHPO4.2H2O) |

| Uric acid and urate containing stones |

| Infection stones |

| Solitary kidney (The solitary kidney itself does not have a particular increased risk of stone formation, but the prevention of a potential stone recurrence is of more importance) |

| Diseases associated with Kidney stone formation |

| Hyperparathyroidism |

| Nephrocalcinosis |

| Gastrointestinal diseases or disorders (i.e. jejuno-ileal bypass, intestinal resection, Crohn’s disease, malabsorptive conditions) |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Genetically determined stone formation |

| Cystinuria (type A, B, AB) |

| Primary hyperoxaluria (PH) |

| Renal tubular acidosis (RTA) type I |

| 2,8-dihydroxyadenine |

| Xanthinuria |

| Lesh-Nyhan-Syndrome |

| Cystic fibrosis |

| Anatomical abnormalities associated with Kidney stone formation |

| Medullary sponge kidney (tubular ectasia) |

| UPJ obstruction |

| Calyceal diverticulum, calyceal cyst |

| Ureteral stricture |

| Vesico-uretero-renal reflux |

| Horseshoe kidney |

| Ureterocele |

| Urinary diversion (via enteric hyperoxaluria) |

| Neurogenic bladder dysfunction |

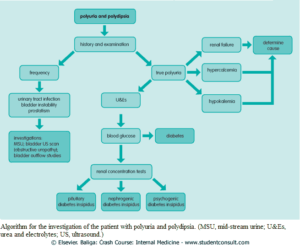

Diagnosis of Kidney and Urinary Stones

Standard evaluation of a patient includes taking a detailed medical history and physical examination. The clinical diagnosis should be supported by an appropriate imaging procedure.

| Recommendation for Diagnosis of Urinary Stones | LE | GR |

| In patients with fever or a solitary kidney, and when the diagnosis of stone is in doubt, immediate imaging is indicated. | 4 | A* |

Ultrasonography should be used as the primary procedure. KUB should not be performed in case an NCCT (Non-contrast enhanced computed tomography) is considered.

Evaluation of Patients with Acute Flank Pain

Non-contrast enhanced computed tomography (NCCT) has become the standard for diagnosis of acute flank pain and has higher sensitivity and specificity than IVU.

Indinavir stones are the only stones not detectable on NCCT.

| Recommendation for Evaluation of Patients with Acute Flank Pain | LE | GR |

| Use NCCT in confirming a stone diagnosis in pts presenting with acute flank pain because it is superior to IVU. | 1a | A |

Biochemical Work-up for Urolithiasis

Each emergency patient with urolithiasis needs a succinct biochemical work-up of urine and blood besides the imaging studies. At that point no difference is made between high and low risk patients.

| Recommendation for Biochemical Work-up of Urolithiasis : Basic analysis Emergency stone patient | |

| Urine | GR |

| Urinary sediment/dipstick test out of spot urine sample for: red cells / white cells / nitrite / urine pH level by approximation | A* |

| Urine culture or microscopy | A |

| Blood | |

| Serum blood sample creatinine / uric acid / ionized calcium / sodium / potassium | A* |

| Blood cell count CRP | A* |

| If intervention is likely or planned: Coagulation test (PTT and INR) | A* |

Examination of sodium, potassium, CRP, and blood coagulation time can be omitted in the non-emergency stone patient.

Only patients at high risk for stone recurrences should undergo a more specific analytical programme (see section

MET below).

Analysis of stone composition should be performed in:

- All first-time stone formers (GR: A) – and repeated in case of:

- Recurrence under pharmacological prevention

- Early recurrence after interventional therapy with complete stone clearance

- Late recurrence after a prolonged stone-free period (GR: B)

The preferred analytical procedures are:

- X-ray diffraction

- Infrared spectroscopy

Wet chemistry generally deems as obsolete.

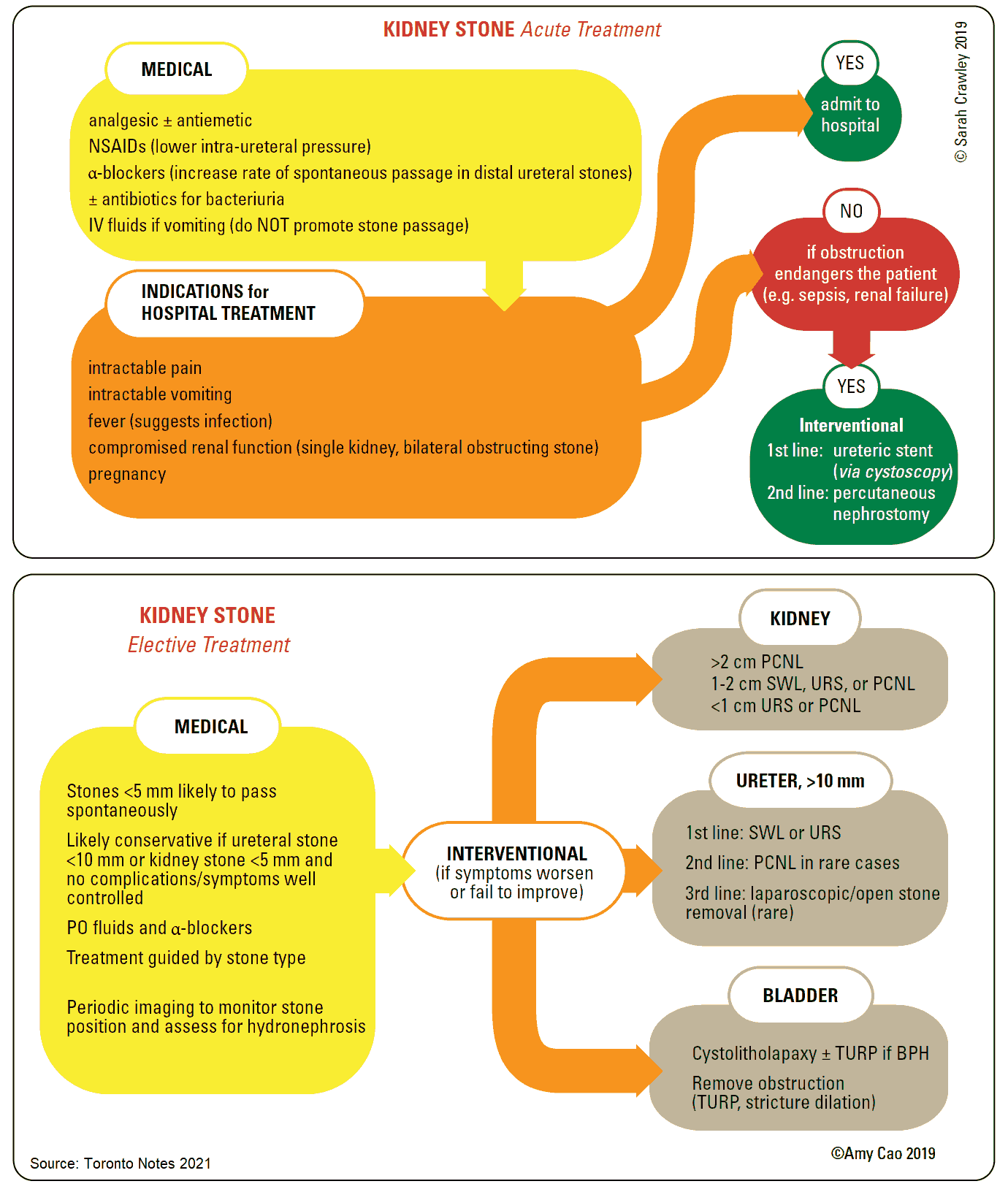

Acute Treatment of a Patient with Renal Colic

Pain relief is the first therapeutic step in patients with an acute stone episode.

| Recommendations for pain relief during and prevention of recurrent renal colic | LE | GR |

| First-line treatment: treatment should be started with an NSAID Diclophenac sodium*, Indomethacin, Ibuprofen. | 1B | A |

| Second-line treatment: Hydromorphine Pentazocine Tramadol | 4 | C |

| Diclofenac sodium* is recommended to counteract recurrent pain after an episode of ureteral colic. | 1b | A |

| Third-line treatment: Spasmolytics (metamizole sodium etc.) are alternatives which may be given in circumstances in which parenteral administration of a non-narcotic agent is mandatory. |

Alpha-blocking agents, given on a daily basis, also reduce the number of recurrent colics. If pain relief cannot be achieved by medical means, drainage, using stenting or percutaneous nephrostomy, or stone removal, should be carried out.

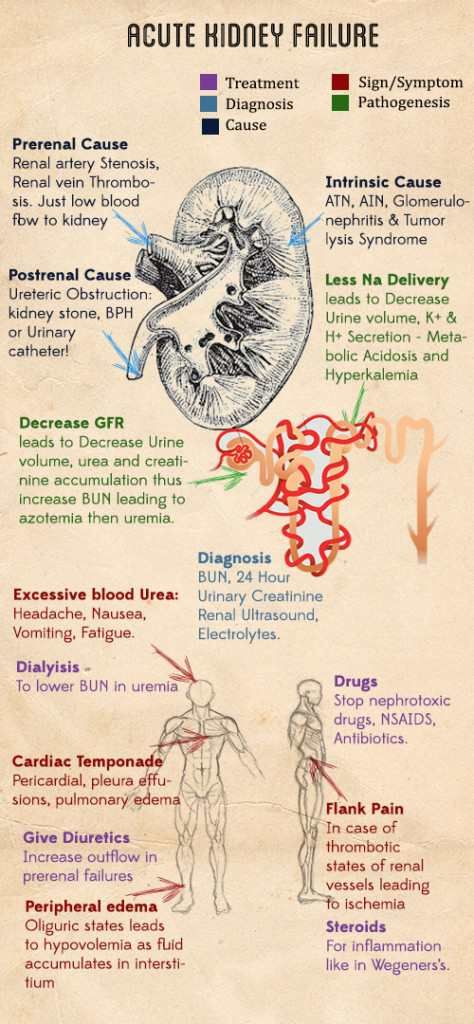

Management of sepsis in the obstructed kidney

The obstructed, infected kidney is a urological emergency.

| Recommendation for Management of sepsis in the obstructed kidney | LE | GR |

| For septic patients with obstructing stones, the collecting system should be urgently decompressed, using either percutaneous drainage or ureteral stenting. | 1b | A |

| Definitive treatment of the stone should be delayed until sepsis is resolved. | 1b | A |

In exceptional cases, with severe sepsis and/or the formation of abscesses, an emergency nephrectomy may become necessary.

| Further Measures for sepsis in the obstructed kidney – Recommendations | GR |

| Collect urine following decompression for antibiogram. | A* |

| Start antibiotic treatment immediatedly thereafter (+ intensive care if necessary). | A* |

| Revisit antibiotic treatment regimen following antibiogram findings. | A* |

Urinary Stone Relief

When deciding between active stone removal and conservative treatment using MET, it is important to carefully consider all the individual circumstances of a patient that may affect treatment decisions.

Observation of Ureteral Stones

| Recommendations for Observation of Ureteral Stones | LE | GR |

| In a patient who has a newly diagnosed ureteral stone < 10 mm and if active stone removal is not indicated, observation with periodic evaluation is an option as initial treatment. | 1a | A |

| Such patients may be offered appropriate medical therapy to facilitate stone passage during the observation period*. | 1a | A |

Observation of Kidney Stones

| Recommendations for Observation of Kidney Stones | GR* |

| Kidney stones should be treated in case of stone growth, formation of de novo obstruction, associated infection, and acute and/or chronic pain. | A |

| Patient’s comorbidities and preferences (social situation) need to be taken into consideration when making a treatment decision. | C |

| If kidney stones are not treated, periodic evaluation is needed. | A |

Medical Expulsive Therapy (MET)

For patients with ureteral stones that are expected to pass spontaneously, NSAID tablets or suppositories (i.e. diclofenac sodium, 100-150 mg/day, over 3-10 days) may help to reduce inflammation and the risk of recurrent pain.

Alpha-blocking agents, given on a daily basis, also reduce the number of recurrent colic (LE: 1a). Tamsulosin, has been the most commonly used alpha blocker in studies.

| Recommendations for MET (Medical Expulsive Therapy) | LE | GR |

| For MET, alpha-blockers or nifedipine are recommended. | A | |

| Patients should be counselled about the attendant risks of MET, including associated drug side effects, and should be informed that it is administered as ‘off-label’ use. | A* | |

| Patients, who elect for an attempt at spontaneous passage or MET, should have wellcontrolled pain, no clinical evidence of sepsis, and adequate renal functional reserve. | A | |

| Patients should be followed to monitor stone position and to assess for hydronephrosis. | 4 | A* |

| MET in children cannot be recommended due to the limited data in this specific population. | 4 | C |

Corticosteroids in combination with alpha-blockers may expedite stone expulsion compared to alpha-blockers alone (LE: 1b).

| Statements |

| MET has an expulsive effect also on proximal ureteral stones. |

| After ESWL for ureteral or renal stones, MET seems to expedite and increase stone-free rates, reducing additional analgesic requirements. |

Chemolytic dissolution of stones

Oral or percutaneous irrigation chemolysis of stones can be a useful first-line therapy or an adjunct to ESWL, PNL, URS, or open surgery to support elimination of residual fragments. However, its use as first-line therapy may take weeks to be effective.

Percutaneous Irrigation Chemolysis

| Recommendations for Percutaneous Irrigation Chemolysis | GR |

| In percutaneous chemolysis, at least two nephrostomy catheters should be used to allow irrigation of the renal collecting system, while preventing chemolytic fluid draining into the bladder and reducing the risk of increased intrarenal pressure. | A |

| Pressure- and flow-controlled systems should be used if available. | A |

Methods of percutaneous irrigation chemolysis

| Stone composition | Irrigation solution | Comments |

| Struvite Carbon apatite | 10% Hemiacidrin with pH 3.5-4 Suby’s G | Combination with ESWL for staghorn stones Risk of cardiac arrest due to hypermagnesaemia |

| Brushite | Hemiacidrin Suby’s G | Can be considered for residual fragments |

| Cystine | Trihydroxymethylaminomethan (THAM; 0.3 or 0.6 mol/L) with pH range 8.5-9.0 N-acetylcysteine (200 mg/L) | Takes significantly longer time than for uric acid stones Used for elimination of residual fragments |

| Uric acid | Trihydroxymethylaminomethan (THAM; 0.3 or 0.6 mol/L) with pH range 8.5-9.0 | Oral chemolysis is the preferred option |

Oral Chemolysis

Oral chemolitholysis is efficient for uric acid calculi only. The urine pH should be adjusted to between 7.0 and 7.2.

| Recommendations for Oral Chemolysis | GR |

| The dosage of alkalising medication must be modified by the patient according to the urine pH, which is a direct consequence of the alkalising medication. | A |

| Dipstick monitoring of urine pH by the patient is required at regular intervals during the day. Morning urine must be included. | A |

| The physician should clearly inform the patient of the significance of compliance. | A |

ESWL

The success rate for ESWL will depend on the efficacy of the lithotripter and on:

- Size, location of stone mass (ureteral, pelvic or caliceal), and composition (hardness) of the stones

- Patient’s habitus

- Performance of ESWL

Contraindications of ESWL

- Pregnancy

- Bleeding diatheses

- Uncontrolled urinary tract infections

- Severe skeletal malformations and severe obesity, which will not allow targeting of the stone

- Arterial aneurism in the vicinity of the stone treated

- Anatomical obstruction distal of the stone

Stenting prior to ESWL

A double-J stent reduces the complications (evidence of renal colic) but does not reduce formation of steinstrasse or infective complications.

Routine stenting is not recommended as part of ESWL treatment of ureteric stones.

Best clinical practice (best performance) for ESWL

Patients with a pacemaker can be treated with ESWL provided the patient’s cardiologist is consulted before ESWL is undertaken. Patients with implanted cardioverter defibrillators must be managed with special care, as some devices need to be de-activated during ESWL.

The optimal shock wave frequency is 1.0 (to 1,5) Hz.

Number of shock waves, energy setting and repeat treatment sessions

- The number of shock waves that can be delivered at each session depends on the type of lithotripter and shockwave power.

- Starting ESWL using a lower energy setting with step-wise power ramping prevents renal injury.

- Clinical reality is that repeat sessions are feasible (within 1 day in case of ureteral stones).

Procedure control

The results of treatment are operator dependent. Careful imaging control of localisation will contribute to the quality of outcome.

Pain control

Careful control of pain during treatment is necessary to limit pain induced movements and excessive respiratory excursions.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

No standard prophylaxis prior to ESWL is recommended.

Antibiotics should be given before ESWL and continued for at least 4 days after treatment, in the case of infected stones or bacteriuria.

Medical expulsive therapy (MET) after ESWL

MET after ESWL for ureteral or renal stones can expedite expulsion and increase stone free rates, along with a reduction in additional analgesic requirements.

Percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy (PNL)

| Recommendation for Percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy (PNL) | GR |

| Ultrasonic, ballistic and Ho:YAG devices are recommended for intracorporeal lithotripsy using rigid nephroscopes. | A* |

| When using flexible instruments, the Ho:YAG laser is currently the most effective device available. | A* |

Best clinical practice (best performance) for Percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy (PNL)

Contraindications for Percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy (PNL) :

- All contraindications for general anaesthesia apply.

- Untreated urinary infection.

- Atypical bowel interposition.

- Tumour in the presumptive access tract area.

- Potential malignant tumour of the kidney.

- Pregnancy (conservative stone treatment should be considered first, where possible (GR: A).

Pre-procedural imaging, which includes a contrast media study, is mandatory to assess stone size, the anatomy of the collecting system, and ensure safe access to the kidney stone.

Positioning of the patient for PNL: prone or supine?

Traditionally, the patient is positioned prone for PNL, however supine position has been described, showing advantages in shorter operating time, the possibility of simultaneous retrograde transurethral manipulation, an easier anaesthesia and disadvantages like limitations in the maneuvrability of instruments and the need of appropriate equipment.

Nephrostomy and stents after PNL

In uncomplicated cases, tubeless (without nephrostomy tube) or totally tubeless (without nephrostomy tube and without ureteral stent) PNL procedures provide a safe alternative.

Ureterorenoscopy (URS)

Best clinical practice in Ureterorenoscopy (URS)

Before the procedure, the following information should be available (LE: 4):

- Patient’s history

- Physical examination (i.e. to detect anatomical and congenital abnormalities)

- Thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors/anticoagulation treatment should be discontinued. However, URS can be performed in patients with bleeding disorders, with only a moderate increase in complications

- Imaging

Short-term antibiotic prophylaxis (< 24 hours) should be administered.

Contraindications for Ureterorenoscopy (URS)

Apart from a general considerations related to general anaesthesia, URS can be performed in all patients without any specific contraindications.

Access to the upper urinary tract

Most interventions are performed under general anaesthesia, although it is possible to use spinal anaesthesia. Intravenous sedation is possible for distal stones, especially in women. Antegrade URS is an option for large, impacted proximal ureteral calculi.

Safety aspects for Ureterorenoscopy (URS)

Fluoroscopic equipment must be available in the operating room. If ureteral access is not possible, the insertion of a double-J stent followed by URS after a delay of 7-14 days offers an appropriate alternative to dilatation.

Placement of a safety wire is recommended.

Ureteral access sheaths

Hydrophilic-coated ureteral access sheaths (UAS), can be inserted via a guide wire, with the tip placed in the proximal ureter. In patients with large stone mass UAS promotes improved stone-free rates and reduced OR-time.

Stone extraction with Ureterorenoscopy (URS)

The aim of endourological intervention is to achieve complete stone removal, as ‘smash and go’ strategies leave patients with a higher risk of stone regrowth and post-operative complications.

Recommendation: Ho:YAG laser lithotripsy is the preferred method when carrying out (flexible) URS. (GR: B)

| Recommendations for Stone extraction with Ureterorenoscopy (URS) | LE | GR |

| Stone extraction using a basket without endoscopic visualisation of the stone (blind basketing) should not be performed. | 4 | A* |

| Nitinol baskets preserve the tip deflection of flexible ureterorenoscopes, and the tipless design reduces the risk of mucosa injury. | 3 | B |

| Nitinol baskets are most suitable for use in flexible URS. | 3 | B |

Stenting prior to and after URS

Pre-stenting facilitates the ureteroscopic management of stones, improves the stone-free rate, and reduces the complication rate. Stents should be inserted in patients who are at increased risk of complications.

Recommendation: Stenting is optional before and after uncomplicated URS. (LE: 1a) (GR: A)

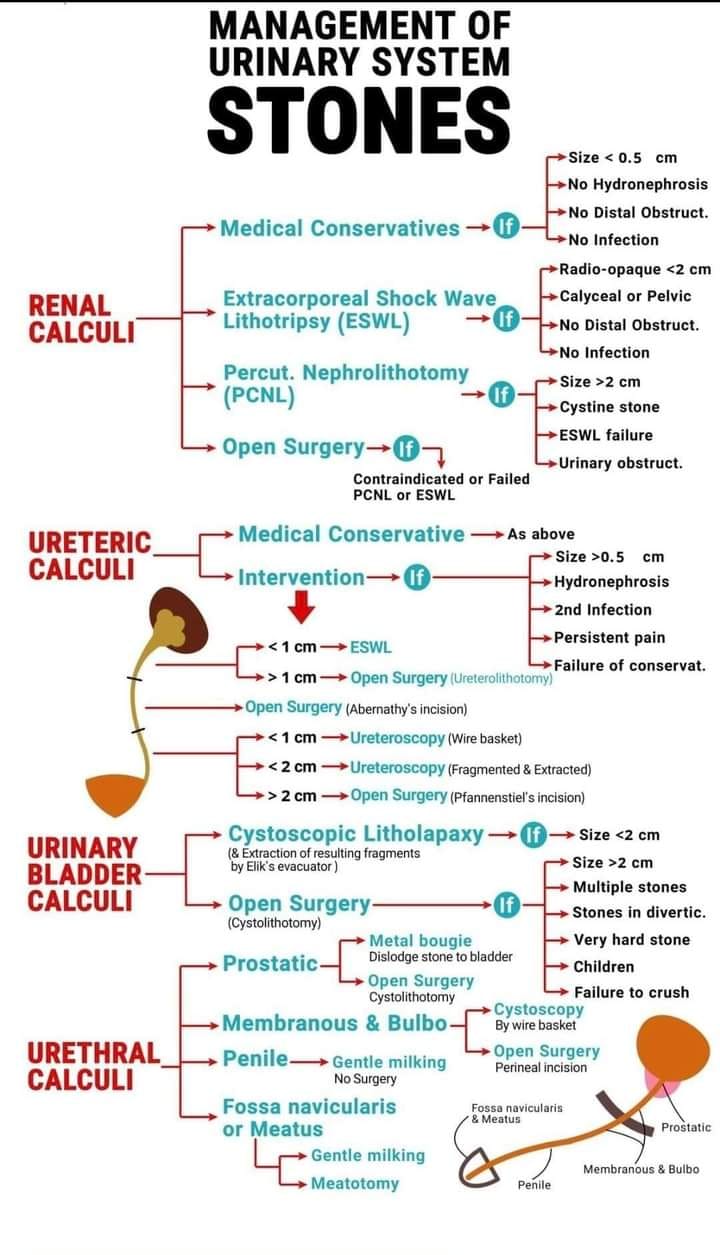

Open Surgery for Urolithiasis (Urinary Stones)

Most complex (staghorn) stones, should be approached primarily with PNL or a combination of PNL and ESWL. Open surgery may be a valid primary treatment option in selected cases.

Indications for open surgery of Urolithiasis :

- Complex stone burden

- Treatment failure of ESWL and/or PNL, or failed ureteroscopic procedure

- Intrarenal anatomical abnormalities: infundibular stenosis, stone in the calyceal diverticulum (particularly in an anterior calyx), obstruction of the ureteropelvic junction, stricture

- Morbid obesity

- Skeletal deformity, contractures and fixed deformities of hips and legs

- Co-morbid medical disease

- Concomitant open surgery

- Non-functioning lower pole (partial nephrectomy), nonfunctioning kidney (nephrectomy)

- Patient choice following failed minimally invasive procedures; the patient may prefer a single procedure and avoid the risk of needing more than one PNL procedure

- Stone in an ectopic kidney where percutaneous access and ESWL may be difficult or impossible

- For the paediatric population, the same considerations apply as for adults.

Laparoscopic surgery of Urolithiasis

Laparoscopic urological surgery has increasingly replaced open surgery.

Indications for laparoscopic kidney-stone surgery include:

- Complex stone burden

- Failed previous ESWL and/or endourological procedures

- Anatomical abnormalities

- Morbid obesity

- Nephrectomy in case of non-functioning kidney

Indications for laparoscopic ureteral stone surgery include:

- Large, impacted stones

- Multiple ureteral stones

- In cases of concurrent conditions requiring surgery

- When other non-invasive or low-invasive procedures have failed

- Laparoscopic ureterolithotomy should be considered when other non-invasive or low-invasive procedures have failed.

| Recommendations for Laparoscopic surgery of Urolithiasis | LE | GR |

| Laparoscopic or open surgical stone removal may be considered in rare cases where ESWL, URS, and percutaneous URS fail or are unlikely to be successful. | 4 | C |

| When expertise is available, laparoscopic surgery should be the preferred option before proceeding to open surgery. An exception will be complex renal stone burden and/or stone location. | 4 | C |

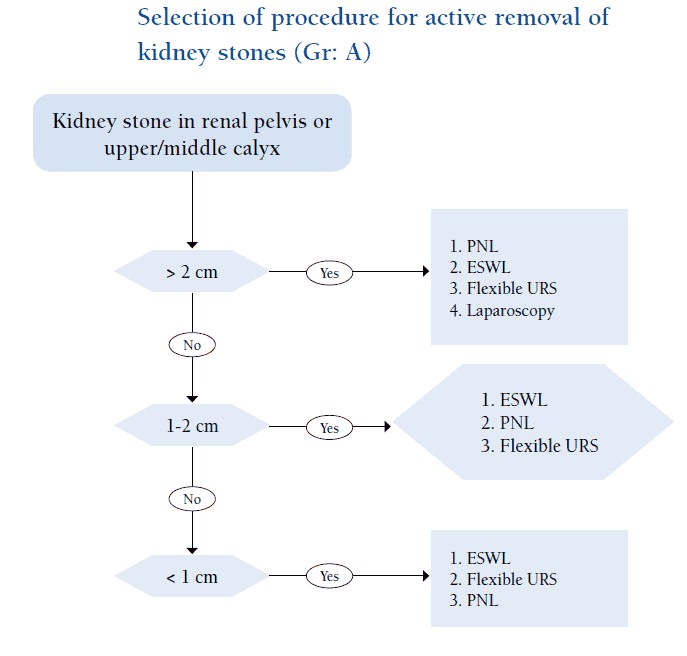

Indication for active urinary stone removal and selection of procedure

- Ureter:

- Stones with a low likelihood of spontaneous passage

- Persistent pain in spite of adequate pain medication

- Persistent obstruction

- Renal insufficiency (renal failure, bilateral obstruction, single kidney)

- Kidney:

- Stone growth

- Stones in high-risk patients for stone formation

- Obstruction caused by stones

- Infection

- Symptomatic stones (e.g. pain, haematuria)

- Stones > 15 mm

- Stones < 15 mm if observation is not the option of choice • Patient preference (medical and social situation) • > 2-3 years persistent stones

The suspected stone composition might influence the choice of treatment modality.

| Statements | LE |

| For asymptomatic caliceal stones in general, active surveillance with an annual follow-up evaluation of symptoms and the status of the stone by appropriate means (KUB, ultrasonography [US], NCCT) is an option for a reasonable period (the first 2–3 years), whereas intervention should be considered after this period provided patients are adequately informed. | 4 |

| Observation might be associated with a greater risk of necessitating more invasive procedures. | 4 |

Urinary Stone Removal

| Recommendations for Urinary Stone Removal | GR |

| Urine culture is mandatory before any treatment is planned. | A |

| Urinary infection should be treated when stone removal is planned. | |

| Salicylates should be stopped before planned stone removal. | B |

| If intervention for stone removal is essential and salicylate therapy should not be interrupted, retrograde URS is the preferred treatment of choice. |

Radiolucent uric acid stones, but not sodium urate or ammonium urate stones, can be dissolved by oral chemolysis. Determination is done by urinary pH. Careful monitoring of radiolucent stones during/after therapy is imperative. (GR*: A)

Selection of procedure for active stone removal of ureteral stones

| First choice | Second choice | |

| Proximal ureter < 10 mm | ESWL | URS |

| Proximal ureter > 10 mm | URS (retrograde or antegrade) or ESWL | URS (retrograde or antegrade) or ESWL |

| Distal ureter < 10 mm | URS or ESWL | URS or ESWL |

| Distal ureter > 10 mm | URS | ESWL |

Patients should be informed that URS is associated with a better chance of achieving stone-free status with a single procedure, but has higher complication rates.

Recommendation: Percutaneous antegrade removal of ureteral stones is an alternative when ESWL is not indicated or has failed, and when the upper urinary tract is not amenable to retrograde URS.

Steinstrasse occurs in 4% to 7% cases of ESWL, the major factor of formation of steinstrasse is stone size.

| Recommendations for Steinstrasse | LE | GR |

| Medical expulsion therapy increases the stone expulsion rate of steinstrasse. | 1b | A |

| Performing of percutaneous nephrostomy is indicated in evidence of UTI/ fever associated with steinstrasse. | 4 | C |

| Performing of ESWL is indicated in the treatment of steinstrasse when larger stone fragments are presented. | 4 | C |

| Performing of ureteroscopy is indicated the treatment of symptomatic steinstrasse and in treatment failures. | 4 | C |

Residual Urinary Stones

| Recommendations for Residual Urinary Stones | LE | GR |

| Identification of biochemical risk factors and appropriate stone prevention is particularly indicated in patients with residual fragments or stones. | 1b | A |

| Patients with residual fragments or stones should be followed up regularly to monitor the course of their disease. | 4 | C |

| After ESWL and URS, adjunctive treatment with tamsulosin could improve fragment clearance and reduce the probability of residual stones. | 1a | A |

| For well-disintegrated stone material residing in the lower calix, inversion therapy during high diuresis and mechanical percussion facilate stone clearance. | 1a | B |

The indication for active stone removal and selection of the procedure is based on the same criteria as for primary stone treatment and also includes repeat ESWL.

Management of Urinary Stones and Related Problems During Pregnancy

Recommendations (GR: A*):

- Ultrasonography is the method of choice as primary diagnostic imaging.

- A limited IVU, MRU, or isotope renography are a useful diagnostic methods.

- Following the establishment of the correct diagnosis, conservative management should be the first-line treatment for all non-complicated cases of urolithiasis in pregnancy.

- If intervention becomes necessary, placement of a internal stent, percutaneous nephrostomy, or ureteroscopy are treatment options.

- Regular follow-up until final stone removal is necessary due to higher lithogenic activity during pregnancy.

Management of Urinary Stone Problems in Children

Spontaneous passage of a stone and of fragments after ESWL is more likely to occur in children than in adults (LE: 4). For paediatric patients, the indications for ESWL and PNL are similar to those in adults, however they pass fragments more easily. Children with renal stones with a diameter up to 20 mm (~300 mm2) are ideal candidates for ESWL.

Recommendation: US evaluation is the first choice for imaging in children and should include the kidney, the filled bladder and adjoining portions of the ureter.

Stones in exceptional situations

Caliceal diverticulum stones

- ESWL, PNL (if possible) or RIRS (retrograde intrrenal surgery via flexible ureteroscopy).

- Can also be removed using video-endoscopic retroperitoneal surgery.

- If there is only a narrow communication between the diverticulum and the renal collecting system, well-disintegrated stone material will remain in the original position.

- Patients may become asymptomatic due to stone disintegration only.

Horseshoe kidneys

- Can be treated in line with the stone treatment options described above.

- Passage of fragments after ESWL might be poor.

Patients with obstruction of the ureteropelvic junction

- When the outflow abnormality has to be corrected, stones can be removed with either percutaneous endopyelotomy or open reconstructive surgery.

- Transureteral endopyelotomy with Ho:YAG laser endopyelotomy can also be used to correct this abnormality.

- Incision with an Acucise balloon catheter might also be considered, provided the stones can be prevented from falling into the pelvo-ureteral incision.

Stones in transplanted kidneys

- Use of PNL is recommended, however ESWL or (flexible) ureteroscopy are valuable alternatives.

Stones in patients with urinary diversion

- Individual management necessary.

- For smaller stones ESWL is effective.

- PNL and antegrade flexible URS are frequently used endourological procedures.

Stones formed in a continent reservoir

- Present a varied and often difficult problem.

- Each stone problem must be considered and treated individually.

Stones in patients with neurogenic bladder disorder

- For stone removal all methods apply based on individual situation.

- Careful patient follow-up and effective precentive strategies are important.

General considerations for recurrence prevention of urinary stones (all stone patients)

- Drinking advice (2.5 – 3L/day, neutral pH)

- Balanced diet

- Lifestyle advice

High-risk patients: Urinary Stone-specific metabolic work-up and pharmacological recurrence prevention

Pharmacological stone prevention is based on a reliable stone analysis and the laboratory analysis of blood and urine including two consecutive 24-hours urine samples.

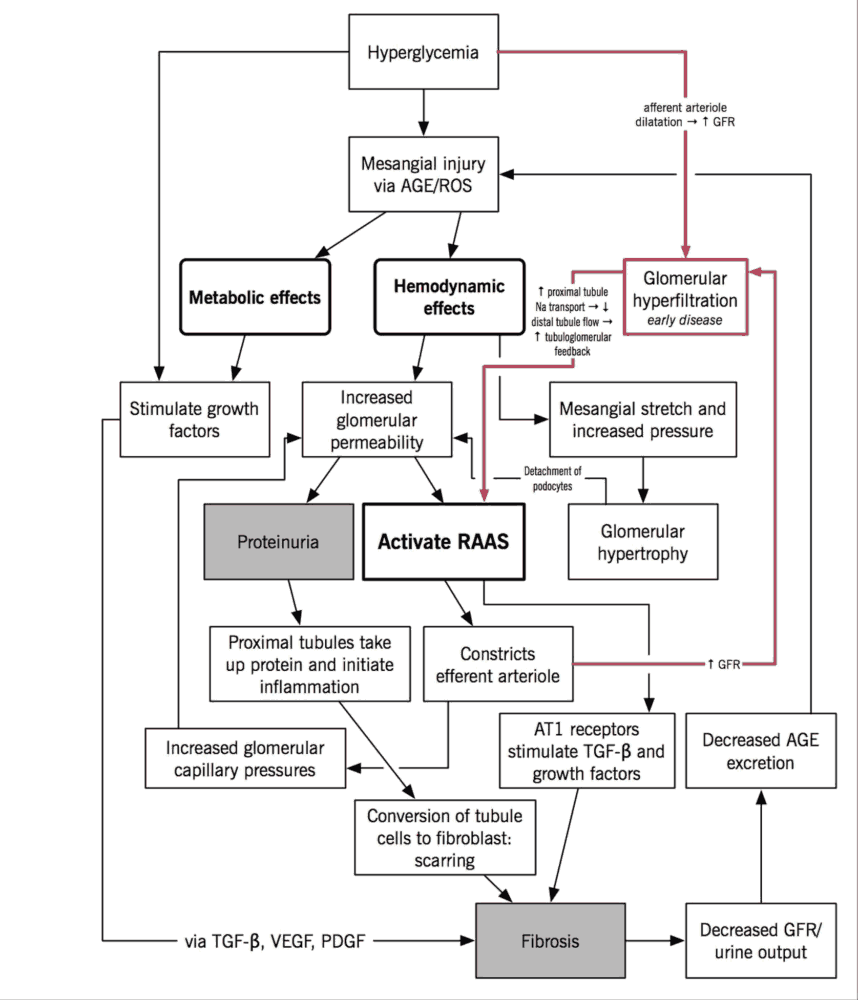

Pharmacological treatment of Calcium Oxalate Stones

(Hyperparathyreoidism excluded by blood examination)

| Risk factor | Suggested treatment | LE | GR |

| Hypercalciuria | Thiazide + potassium citrate | 1a | A |

| Hyperoxaluria | Oxalate restriction | 2b | A |

| Hypocitraturia | Potassium citrate | A | |

| Enteric hyperoxaluria | Potassium citrate Calcium supplement Oxalate absorption | C B B | |

| Small urine volume | Increased fluid intake | A | |

| Distal renal tubular acidosis | Potassium citrate | B | |

| Primary hyperoxaluria | Pyridoxine | B |

Pharmacological treatment of Calcium Phosphate Stones

| Risk factor | Rationale | Medication |

| Hypercalciuria | Calcium excretion 8 mmol/day | Hydrochlorothiazide, initially 25 mg/day, increasing up to 50 mg/day |

| Inadequate urine pH | pH constantly > 6.2 | L-Methionine, 200- 500 mg 3 times daily, with the aim of reducing urine pH to 5.8-6.2 |

| Urinary tract infection | Eradication of urea-splitting bacteria | Antibiotics |

Hyperparathyroidism and Urinary Stones

Elevated levels of ionized calcium in serum (or total calcium and albumin) require assessment of intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) to confirm or exclude suspected hyperparathyroidism (HPT). If HPT is suspected, a neck exploration should be carried out to confirm the diagnosis. Primary HTP can only be cured by surgery.

Pharmacological treatment of uric acid and ammonium urate stones

| Risk factor | Rationale for pharmacological therapy | Medication |

| Inadequate urine pH | Urine pH constantly < 6.0; ‘acidic arrest‘ in uric acid stones Urine pH constantly > 6.5 in ammonium urate stones | Alkaline citrate OR Sodium bicarbonate Prevention: targeted urine pH 6.2-6.8 Chemolitholysis: targeted urine pH 7.0-7.2 Adequate antibiotics in case of urinary tract infection L-Methionine, 200- 500 mg 3 times daily; targeted urine pH 5.8-6.2 |

| Hyperuricosuria | Uric acid excretion > 4.0 mmol/day Hyperuricosuria and hyperuricemia 380 μmol | Allopurinol, 100 mg/day (LE: 3; GR: B) Allopurinol, 100-300 mg/day, depending on kidney function (LE: 4; GR: C) |

Treatment of Struvite and Infection Urinary Stones

| Therapeutic measure recommendations for Struvite and Infection Urinary Stones | LE | GR |

| Surgical removal of the stone material as completely as possible | ||

| Short-term antibiotic course | 3 | B |

| Long-term antibiotic course | 3 | B |

| Urinary acidification: ammonium chloride, 1 g x 2-3 daily | 3 | B |

| Urinary acidification: methionine, 200-500 mg, 1 to 3 times daily | 3 | B |

| Urease inhibition | 1b | A |

Pharmacological treatment of cystine urinary stones

| Risk factor | Rationale for pharmacological therapy | Medication |

| Cystinuria | Cystine excretion > 3.0-3.5 mmol/ day | Tiopronin, 250 mg/day initially, upto a maximum dose of 2 g/day NB: TACHYPHYLAXIS IS POSSIBLE (LE: 3; GR: B) |

| Inadequate urine pH | Improvement of cystine solubility Urine pH optimum 7.5-8.5 | Alkaline Citrate or Sodium Bicarbonate Dosage is according to urine pH (LE: 3, GR: B) |

2,8-dihydroyadenine stones and xanthine urinary stones

Both stone types are rare. In principle, diagnosis and specific prevention is similar to that of uric acid stones.

Investigating a patient with urinary stones of unknown composition

| Investigation | Rationale for investigation |

| Medical history | • Stone history (former stone events, family history) • Dietary habits • Medication chart |

| Diagnostic imaging | • Ultrasound in case of a suspected stone • NCCT (Determination of the Houndsfield unit provides information about the possible stone composition) |

| Blood analysis | • Creatinine • Calcium (ionized calcium or total calcium + albumin) • Uric acid |

| Urinalysis | • Urine pH profile (measurement after each voiding, minimum 4 times a day) • Dipstick test: leucocytes, erythrocytes, nitrite, protein, urine pH, specific weight • Urine culture • Microscopy of urinary sediment (morning urine) |