Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is defined as pneumonia that occurs in a mechanically ventilated patient more than 48 hours after endotracheal intubation.

VAP can occur in up to 27% of all mechanically ventilated patients and is associated with a mortality rate of almost 50%. Approximately half of all episodes of VAP occur within the first 4 days of the initiation of mechanical ventilation.

Increased emergency department (ED) length of stay has been shown to be a risk factor for development of VAP. A number of simple, low-cost interventions can reduce the risk of VAP and can be implemented in the ED.

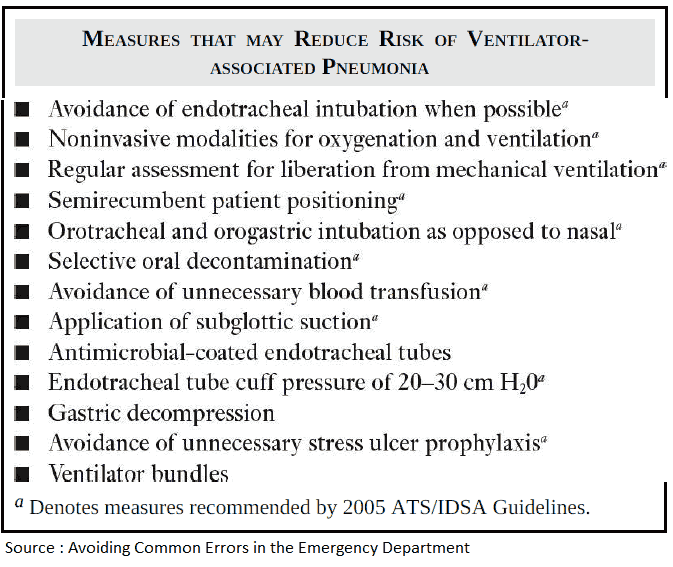

Avoid Endotracheal Intubation When Possible

The greatest risk factors for developing VAP are endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Thus, the best strategy to prevent VAP is to avoid intubation altogether.

Use Noninvasive Modalities for Oxygenation and Ventilation

Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) should be considered in alert patients with respiratory failure due to:

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- congestive heart failure

- neuromuscular weakness

Other noninvasive ventilation modalities, such as high-flow nasal cannula, may be considered in selected patients with hypoxemia.

Use Orotracheal and Orogastric Intubation as Opposed to Nasal

If intubation is necessary, the orotracheal route is preferred over the nasotracheal route with regard to VAP risk.

Semirecumbent Patient Positioning

Numerous studies have shown that the supine position facilitates aspiration of microorganisms into the lower respiratory tract. Elevating the head of the bed to 30 to 45 degrees is a simple, inexpensive intervention that likely reduces the risk for VAP.

A randomized trial demonstrated a threefold reduction in VAP in patients treated in the semirecumbent position compared with patients who remained supine. Mechanically ventilated patients in the ED should be placed in the semirecumbent position unless a contraindication, such as spinal immobilization, exists.

Selective Oral Decontamination

Colonization of the oropharynx has been identified as an independent risk factor for the development of VAP. As a result, mechanically ventilated patients should receive oral decontamination.

A recent Cochrane Review demonstrated a 40% decrease in the odds of developing VAP among patients treated with oral chlorhexidine. The optimal timing of this treatment remains unclear.

Two recent studies showed no benefit for oral decontamination in the prehospital setting or immediately before intubation. Whole-body chlorhexidine bathing also does not appear to decrease risk for VAP or other health care–associated infections.

Application of Subglottic Suction

Endotracheal tubes with special features may also prevent VAP. Several meta-analyses have documented a decreased prevalence of VAP when endotracheal tubes with subglottic suctioning ports were used.

Use of Antimicrobial-Coated Endotracheal Tubes

Numerous studies have attempted to evaluate whether antimicrobial-coated endotracheal tubes reduce VAP risk. A large randomized controlled trial demonstrated reduced incidence of VAP in patients treated with silver-coated endotracheal tubes. Subsequent analyses of the same data also showed a reduced mortality among the patients who developed VAP while intubated with silver-coated endotracheal tubes.

Maintain Endotracheal Tube Cuff Pressure of 20-30 cm H2O

Attention to endotracheal tube cuff pressure may also aid in VAP prevention. ED providers should measure endotracheal tube cuff pressure after intubation. An endotracheal tube cuff pressure maintained at 20 to 30 cm H2O can prevent leakage of bacterial pathogens around the cuff into the lower respiratory tract.

Devices designed to provide continuous control of endotracheal tube cuff pressure throughout the respiratory cycle have not been shown to consistently reduce risk for VAP.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Ventilator Bundle

Many hospitals have adopted “ventilator bundles,” based primarily on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) initiatives to incorporate evidence-based practices into clinical care. The IHI ventilator bundle includes four practices:

- Elevation of the head of the bed to 30 to 45 degrees

- Daily sedation vacations and assessment of readiness to extubate

- Peptic ulcer disease prophylaxis

- Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis.

The impact of the IHI bundle, along with other ventilator bundles, is unclear. Nonetheless, they represent an important effort to implement best practices for VAP prevention.

ED mechanical ventilation bundles that include measures such as arterial blood gas sampling, gastric decompression, early sedation, appropriate initial tidal volume, and quantitative capnography have been shown to improve outcome; however, the role of these bundles strictly in VAP prevention remains uncertain.

Key Points

- The best way to avoid VAP is to avoid unnecessary intubation and mechanical ventilation.

- Elevation of the head of the bed and selective oral decontamination may reduce VAP risk.

- Endotracheal tubes with subglottic suctioning ports or antibiotic coating have been shown to decrease the prevalence of VAP.

- Maintaining endotracheal tube cuff pressure at 20 to 30 cm H2O can prevent leakage of bacteria into the lower respiratory tract.

- Ventilator bundles that have been adapted for the ED may improve patient outcomes.

Suggested Readings

- American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare- associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388–416. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15699079/)

- Bhat R, Goyal M, Graf S, et al. Impact of post-intubation interventions on mortality in patients boarding in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(6):708–711. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25247049/)

- Kollef MH. Prevention of hospital-associated pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(6):1396–1405. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15187525/)

- Shi Z, Xie H, Wang P, et al. Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD008367. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23939759/)

- Wang F, Bo L, Tang L, et al. Subglottic secretion drainage for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(5):1276–1285. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22673255/)