IBS is a long-term, recurring digestive condition marked by stomach pain or discomfort, usually along with changes in bowel movements.

Unlike organic gastrointestinal diseases, IBS is classified as a functional disorder. This means symptoms appear even when standard tests don’t show any physical problems.

IBS is one of the most frequent functional gut disorders seen in clinics, especially by primary care doctors and gastroenterologists.

Epidemiology

An NCBI study reports that the prevalence of IBS ranges from 9% to 23% worldwide. However, reported rates vary based on geographic region and diagnostic criteria used. It is higher in middle- and low-income countries compared to high-income countries.

It affects women more frequently than men. A Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility study states that women are 1.8 times more likely to be diagnosed with IBS than men.

Onset typically occurs in early adulthood, with many patients reporting symptom development before age 35. IBS is also a leading cause of missed workdays and reduced productivity, reflecting its considerable impact on health-related quality of life.

Pathophysiology

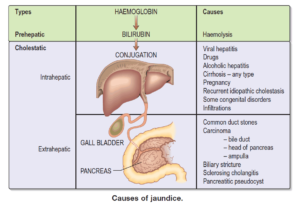

The pathogenesis of IBS is multifactorial, involving complex interactions between the enteric and central nervous systems. Visceral hypersensitivity, altered gastrointestinal motility, low-grade mucosal inflammation, immune activation, and gut microbiota disturbances all contribute to symptom development.

Psychological stress is known to exacerbate symptoms, and comorbid anxiety or depression is frequently observed in IBS populations. As a Healthline article notes, the digestive system and brain constantly exchange messages. Due to this connection, stress can affect IBS symptoms and vice versa.

These overlapping somatic and psychological factors have influenced the way healthcare professionals are trained to approach IBS.

Many patients now prefer caretakers who also have some educational background in mental health. Therefore, demand for family nurse practitioners (FNPs) with mental health education has increased. Many individuals pursuing this career are now enrolling in an FNP and mental health dual nurse practitioner program.

According to Rockhurst University, this program enables students to earn two certifications simultaneously. One of these certifications is FNP, and the other is Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (PMHNP).

This dual competency is particularly relevant in cases where IBS symptoms are heightened by stress or mental health comorbidities. It enables earlier interventions and more individualized management plans.

Clinical Features

People with IBS experience repeated lower belly pain, often alongside changes in how often they have bowel movements and what their stools look like.

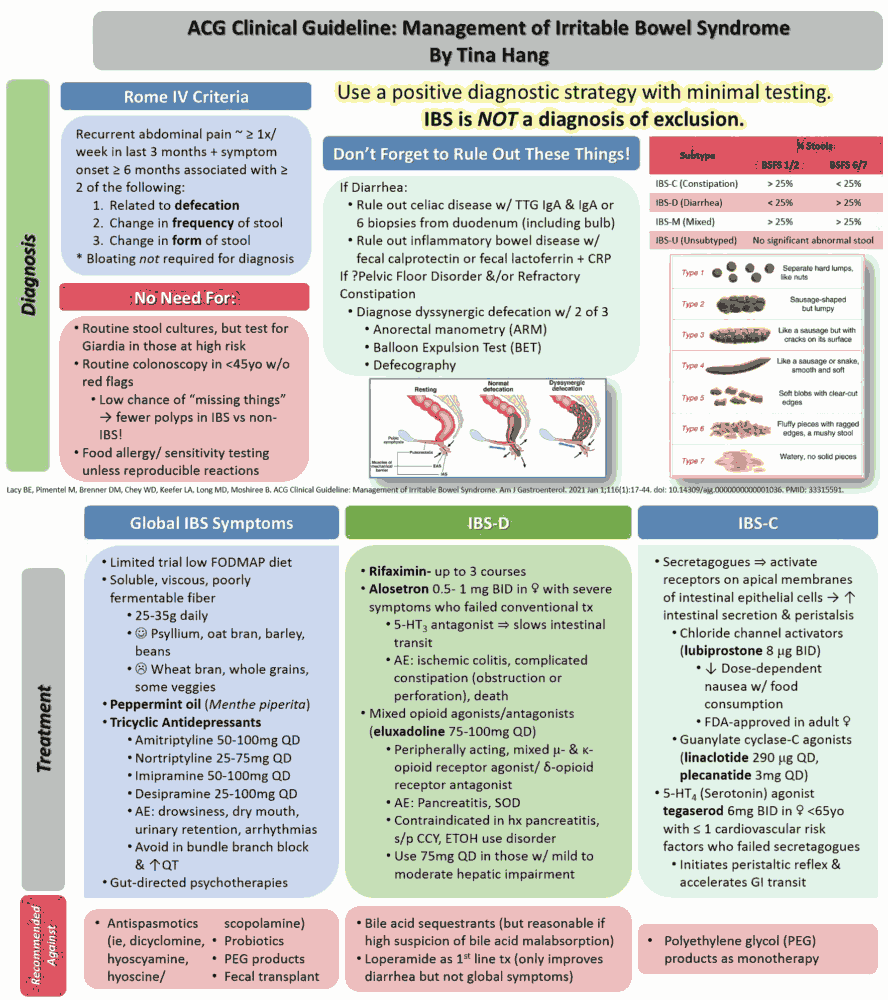

To be diagnosed with IBS according to Rome IV criteria, you need to have had abdominal pain at least once a week for the past three months. This pain must also be linked to at least two of these: pain when pooping, changes in how often you poop, or changes in the appearance of your poop.

According to Medical News Today, the condition is subtyped depending on specific symptoms. For instance, when IBS is combined with constipation, it is categorized as IBS-C. Similarly, association with diarrhea is a subtype of IBS-D. When the condition has mixed bowel habits, it is referred to as IBS-M. And if it is not categorized under those three, it is called IBS-U or unclassified IBS.

It can also be classified as post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS) and post-diverticulitis IBS. This classification is used when it develops as a result of some other conditions, like infectious gastroenteritis and diverticulitis.

IBS symptoms can change over time, and patients might shift between different types of IBS. Other common issues include tiredness, trouble sleeping, and various body aches. This reflects the systemic impact of this functional disorder.

Diagnosis

As noted in a Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology Journal study, the Rome IV criteria are the gold standard used for diagnosing IBS. Laboratory and diagnostic testing should be limited to ruling out organic pathology in the presence of alarm features such as:

- Rectal bleeding

- Unexplained weight loss

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Nocturnal diarrhea

- Family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease

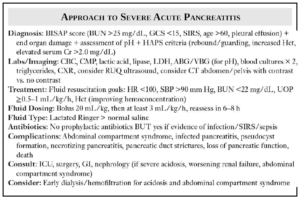

Routine investigations may include:

- Complete blood count (CBC) to rule out anemia or infection

- C-reactive protein (CRP) or fecal calprotectin to exclude inflammatory bowel disease

- Celiac serology in patients with IBS-D or IBS-M

Further evaluation with colonoscopy is generally reserved for patients over age 50 or those presenting with red flag symptoms. Unless there are concerning “red flag” symptoms, extensive scans and lab tests aren’t usually needed.

Management

A combination of lifestyle changes and therapeutic help can manage IBS.

Diet and Lifestyle

Dietary modification plays a central role in IBS management. An NCBI study states that a low FODMAP diet (fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols) is efficient in reducing bloating and improving stool patterns. Trained professionals should guide elimination diets to prevent unnecessary nutritional deficiencies.

Patients with IBS-C often benefit from soluble fiber supplementation, such as psyllium, although insoluble fiber may worsen bloating. Regular physical activity, stress reduction strategies, and sleep regulation are beneficial adjuncts in symptom control.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Pharmacologic treatment should be individualized based on predominant symptoms:

- IBS-C: First-line agents include osmotic laxatives like polyethylene glycol. Prescription therapies, such as linaclotide and lubiprostone, can be used for moderate to severe cases.

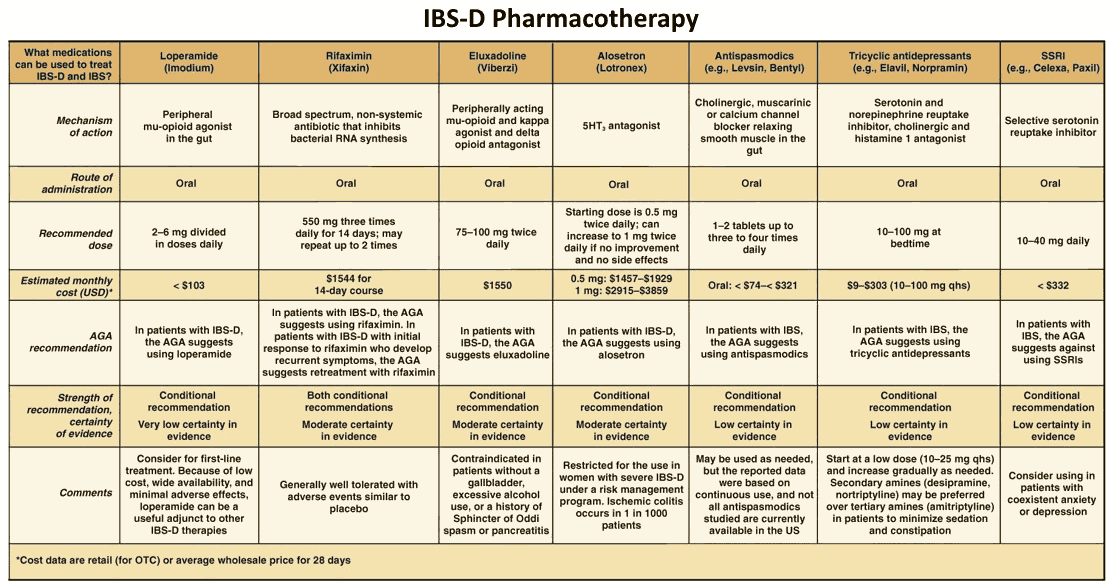

- IBS-D: Options include loperamide, bile acid sequestrants, and rifaximin. In select patients, alosetron (5-HT3 antagonist) may be considered with caution.

- Pain and bloating: Antispasmodics (e.g., dicyclomine or hyoscine) and low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) may be effective for visceral pain. TCAs are preferred in IBS-D, while SSRIs may be helpful in IBS-C when depression coexists.

Psychological Interventions

For those with moderate to severe IBS, psychological treatments are a crucial part of their care. This is particularly true when symptoms are refractory to standard treatment.

Cognitive behavioral therapy, gut-directed hypnotherapy, and mindfulness-based stress reduction have shown symptom improvement in multiple randomized controlled trials. These approaches are particularly effective when applied early in the disease course.

Probiotics

Probiotics may help some patients with global symptom relief, though the evidence base remains mixed. Benefits appear to be strain-specific, and clinical response can be variable. A trial period of 4–8 weeks with a single product is often recommended, with continuation based on symptom response.

Prognosis

IBS is a non-progressive, benign condition, but its chronic and fluctuating nature can significantly impair daily function and quality of life. While symptom resolution is rare, long-term symptom control is achievable with a personalized approach.

Multidisciplinary care models, including dietary guidance, pharmacological therapy, and psychological support, yield the best outcomes. Early recognition and targeted management by trained providers improve both short-term and long-term symptom trajectories.

This article is a guest contribution submitted by a professional healthcare writer and reviewed for accuracy.