Table of Contents

Hyperphosphatemia

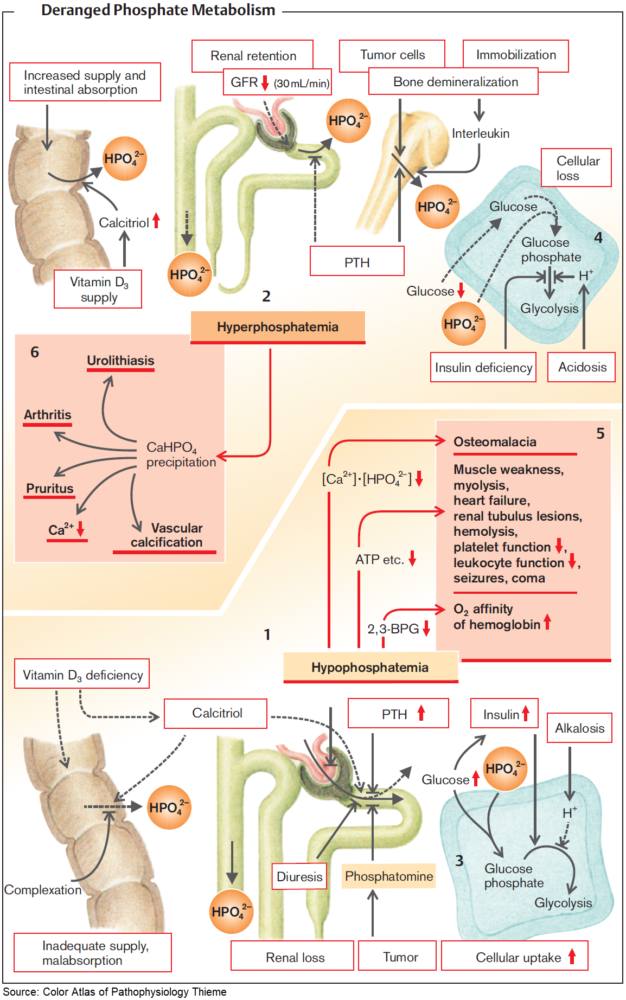

Hyperphosphatemia is defined as a serum level above 2.5 mg/dL, but it is usually clinically significant only when levels are greater than 5 mg/dL.

Although it is rare in the general population, hyperphosphatemia is extremely common in patients with renal insufficiency or renal failure. Almost all patients with renal failure experience hyperphosphatemia at some time during the course of their disease.

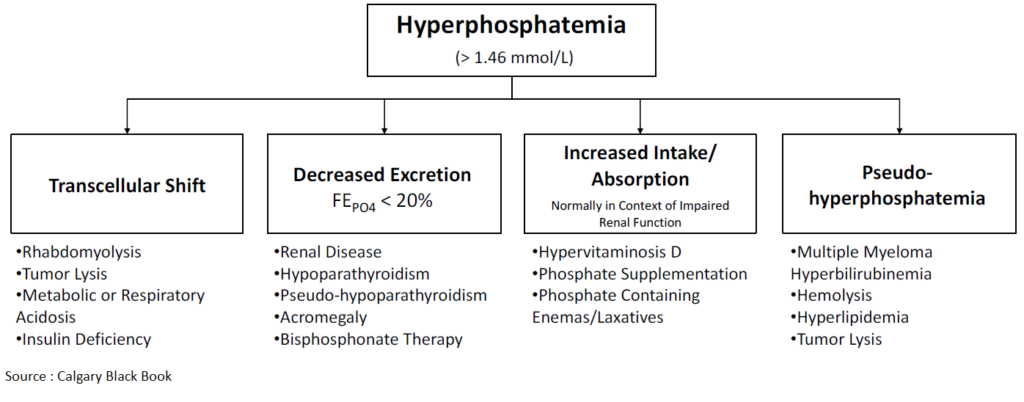

Hyperphosphatemia can occur because of four major pathways:

- Decreased phosphate excretion

- Excessive phosphate intake

- Increased renal tubular reabsorption

- Shift of phosphate from intracellular to extracellular space

Decreased excretion of phosphate combined with excessive intake is the most common mechanism for the development of hyperphosphatemia.

Excessive phosphate intake alone is an uncommon cause of hyperphosphatemia in patients with normal renal function. When patients have glomerular filtration rates below 30 mL/min, the kidneys do not excrete the full amount of ingested phosphate to maintain homeostasis.

Exogenous phosphate, including IV or oral phosphate administration and phosphate enemas and laxatives can cause a large burden on the kidneys if they do not have normal baseline function.

Hypoparathyroidism, vitamin D intoxication, and thyrotoxicosis increase renal phosphate reabsorption and may cause elevated phosphate levels.

Hyperphosphatemia may also occur when there is a large shift of phosphate from the intracellular to the extracellular space and the kidney’s ability to excrete phosphate is overwhelmed. This cause of hyperphosphatemia is seen in rhabdomyolysis, tumor lysis syndrome, and DKA.

Hyperphosphatemia can be a spurious finding in cases of hyperproteinemia, such as multiple myeloma, hyperlipidemia, hemolysis, or hyperbilirubinemia. Drawing of a blood sample from a line containing heparin is another cause of a falsely elevated phosphate level.

Clinical Features of Hyperphosphatemia

Patients with hyperphosphatemia may present with multiple complaints related to electrolyte abnormalities, particularly hypocalcemia. Hyperphosphatemia causes hypocalcemia by precipitating calcium out of the blood and decreasing vitamin D production. It is this secondary hypocalcemia that can cause muscle cramping, tetany, and seizures. Chronic hyperphosphatemia can also lead to metastatic calcifications in joints, tissues, and arteries.

Management of Hyperphosphatemia

Dietary restriction alone may suffice for control of hyperphosphatemia in persons with mild renal insufficiency, but it is inadequate for control in those with overt renal failure. Because most patients presenting with severe hyperphosphatemia also have hypocalcemia, treatment focuses on the correction of both.

In patients with normal renal function, phosphate excretion can be increased by saline infusion coupled with loop diuretics. Hyperphosphatemia usually resolves in 6 to 12 hours in patients with normal renal function.

In patients with hyperphosphatemia with renal failure, hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis should be considered early in the management. Currently, phosphate control is initiated only when hyperphosphatemia occurs, but it may be beneficial to intervene earlier in patients with chronic kidney disease.

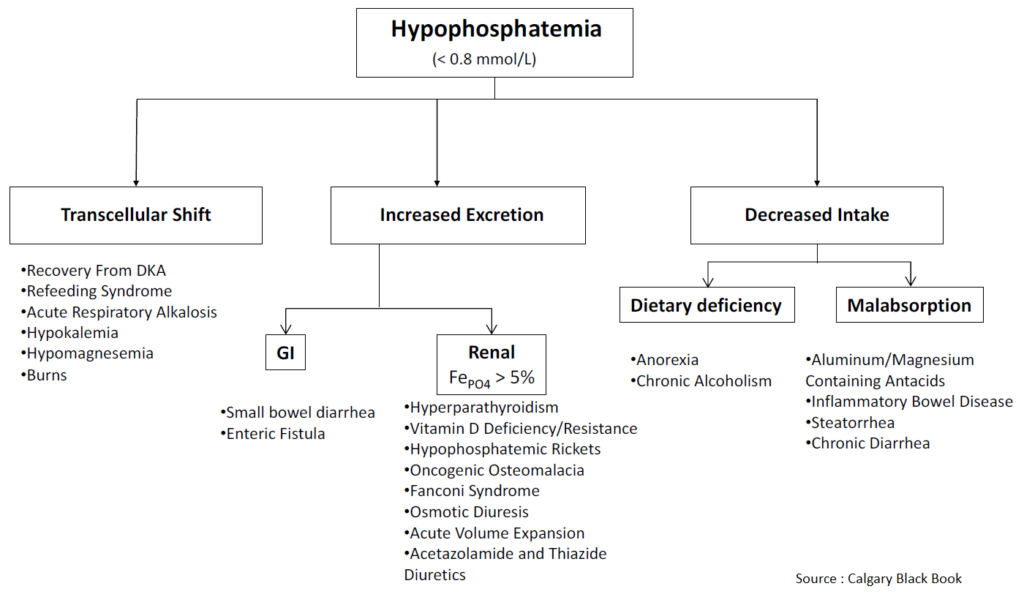

Hypophosphatemia

Hypophosphatemia is defined as mild (2 to 2.5 mg/dL), moderate (1 to 2 mg/dL), or severe (<1 mg/dL). Mild to moderately severe hypophosphatemia is usually asymptomatic and, like hypomagnesemia, often goes unrecognized.

Although most patients remain asymptomatic, severe hypophosphatemia may result in potentially life-threatening complications. Major clinical sequelae usually occur only in severe hypophosphatemia.

Symptoms of hypophosphatemia typically begin to be manifested at serum levels below 1.0 mg/dL. Acute hypophosphatemia is most commonly due to a rapid intracellular shift. Hyperventilation, glucose, insulin, volume expansion, and resolving acidosis can lead to hypophosphatemia by rapid intracellular shift.

The many causes of hypophosphatemia include decreased phosphate intake or increased absorptive states, hyperventilatory states, hormonal and endocrine effects, medications, and disease states.

The ED patients most likely to have hypophosphatemia are those who are malnourished with alcohol withdrawal, acute hyperventilation, or sepsis and patients with DKA or alcohol ketoacidosis in whom reintroduction of insulin and glucose causes phosphate uptake into cells.

Clinical Features of Hypophosphatemia

Mild to moderate hypophosphatemia is usually asymptomatic, but major clinical manifestations can occur with severe hypophosphatemia.

Because phosphate is an essential component to adenosine triphosphate, hypophosphatemia can affect a variety of organ systems and a wide variety of symptoms.

Patients with hypophosphatemia may present with nonspecific complaints including joint pain, myalgias, irritability, and depression. Severe hypophosphatemia can be manifested as seizures, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, insulin resistance, acute tubular necrosis, rhabdomyolysis, and acute respiratory failure.

Management of Hypophosphatemia

We recommend patients with phosphate levels below 2.0 mg/dL be given phosphate repletion; patients with levels below 1.0 mg/ dL necessitate treatment.

Because hypophosphatemia is often coupled with hypokalemia, patients with hypophosphatemia often require potassium repletion as well. Oral phosphorous, 250 to 500 mg twice daily, can be given to stable or asymptomatic patients. IV preparations are available as sodium phosphate (Na2PO4 and NaPO4) or potassium phosphate (K2PO4 and KPO4), and rate of infusion and choice of initial dosage should be based on severity of hypophosphatemia and presence of symptoms.