Table of Contents

The Anxious State

limbic system, in particular the amygdala, facilitates autonomic arousal under conditions of uncertainty or distress. The increase in sympathetic tone contributes to a state of readiness with activation of the “fight-or-flight” response.

Pupils dilate, cardiac output increases, reflexes quicken, and hypervigilance ensues. Although these physiologic reactions may provide benefit during certain stressful situations, in practice, the anxious ED patient reports uneasiness, distress, and feelings of impending doom.

These feelings are frequently observed in the ED as somatic complaints such as chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea, gastrointestinal discomfort, diaphoresis, lightheadedness, weakness, and fatigue.

It is important to note that patients are not generally aware that these symptoms may be associated with anxiety. The pain threshold is also reduced by the anxious state, so patients may complain of severe pain that seems incongruent with their physical exam.

Evaluating the Anxious Patient in the ED

The symptoms of anxiety may be due to:

- the chaotic ED environment (“white coat” anxiety)

- a serious underlying medical condition

- drug or alcohol intoxication or withdrawal

- primary anxiety disorder

More than one condition may be present concurrently. Although it may be tempting to diagnose primary anxiety to arrive at a quick disposition, it is important to address the patient’s symptoms seriously. This helps to establish a relationship of trust and ensures no medical conditions will be overlooked.

Engaging the anxious patient with open-ended questions and listening calmly can help to limit distress and may actually be therapeutic. Determining if environmental factors or life stressors have triggered the episode of anxiety can help to discern exogenous and endogenous anxiety.

Exogenous anxiety in the context of acute environmental stress is frequently amenable to reassurance. These patients will benefit from a discussion with the social worker or referral to a mental health professional.

On the other hand, primary anxiety disorders are endogenous, having genetic and longterm environmental contributions, such as chronic stress. Exacerbations often occur without an identifiable trigger and patients may have a history of recurrent attacks.

If a primary anxiety disorder is suspected, a referral for psychiatric evaluation should be suggested. The anxiety spectrum covers a variety of specific diagnoses. For the purposes of this text, and the emergency provider, it is more important to differentiate between primary and secondary causes of anxiety than to make a specific psychiatric diagnosis.

Suicidal or homicidal ideation must be addressed in any severely anxious patients, leading to consideration for emergent psychiatric evaluation and admission.

It is important to assess drug and alcohol use in all anxious patients. Substance use and withdrawal, in particular alcohol withdrawal, are common causes of anxiety. Stimulants, including caffeine and nicotine, can worsen anxiety and should be avoided by these patients.

Even if a psychiatric etiology is suspected, the workup of anxiety must address the possibility of an underlying medical condition. Missing a myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism in a patient discharged with a diagnosis of anxiety would be disastrous.

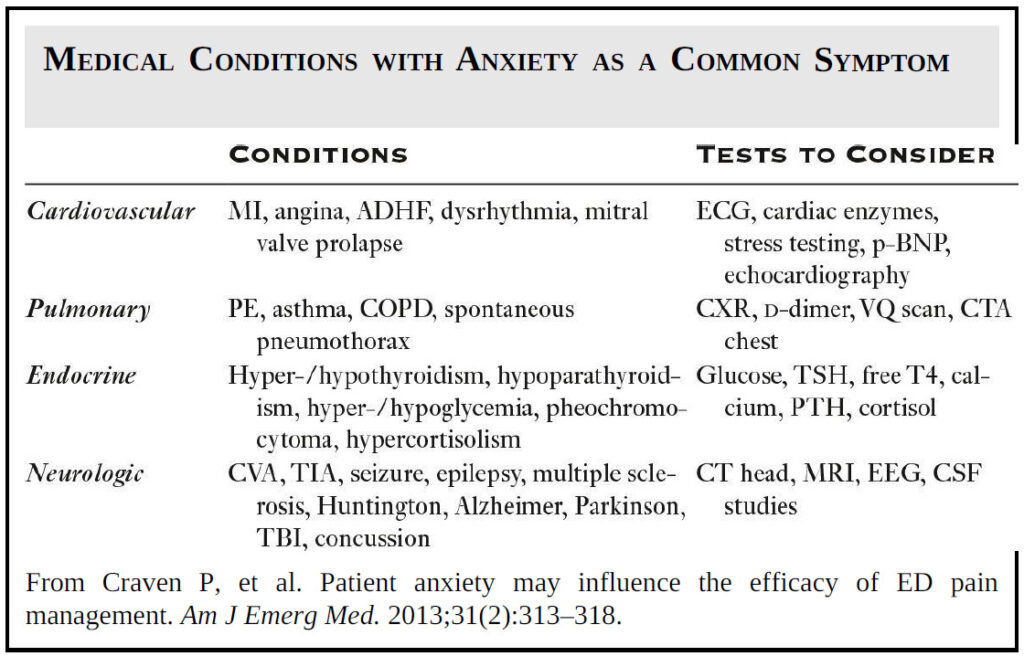

Somatic complaints need to be taken seriously and should guide further workup. Certain cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine, neurologic, and toxicologic pathologies can cause anxiety as a primary symptom (see Image).

The anxious patient may answer yes to almost the entire review of systems checklist. This should lead the provider to consider a workup for common medical etiologies of anxiety, as the history cannot be trusted reliably.

Although anxiety may cause tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypertension, primary medical conditions should be ruled out when abnormal vital signs are present.

Treating the Anxious Patient in the ED

Regardless of the cause, providers should attempt to alleviate symptoms of anxiety in the ED. The therapeutic process may be initiated with calm reassurance during the patient interview.

In some cases, anxiolytics such as diphenhydramine or, in select cases, benzodiazepines can be considered for patients in continued distress.

Appropriate management of the symptoms of anxiety has been shown to reduce morbidity and to increase patient satisfaction. In fact, studies among postmyocardial infarction patients have shown that use of anxiolytics in appropriate patients reduces mortality.

Providers are frequently cited stating that they do not want to “mask” symptoms of an underlying medical condition by administering benzodiazepines. This is not an appropriate reason to leave a patient in continued distress.

Treatment of anxiety is generally achieved through low dose oral benzodiazepines. Patients do not usually require intravenous or intramuscular doses, which are often needed for the agitated ED patient.

On the contrary, use of low-dose benzodiazepines may calm the anxious patient enough to get a more reliable history and exam and may reduce the amount of analgesia required to treat the patient’s pain. Make sure to address the patient’s medication list prior to initiation of anxiolytics.

Caution should always be used when administering benzodiazepines as a paradoxical reaction can occur in certain populations resulting in excessive movement, emotional release, and increased talkativeness.

Benzodiazepines may be less effective in patients that have developed a tolerance through chronic use. Be careful when considering prescribing benzodiazepines for outpatient management. It would be advisable to restrict anxiolytics to a limited prescription for breakthrough anxiety, in order to avoid complications of tolerance and dependence.

Patients requiring ongoing pharmacotherapy should be advised to speak with their primary care physician or a psychiatrist for further management.

Key Points

- Calmly listen to the complaints of anxious patients; your interview can be therapeutic!

- Take all somatic complaints seriously and rule out any potential medical causes of anxiety.

- Consider toxicologic causes of anxiety and counsel patients to avoid anxiogenic substances such as caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and illicit drugs.

- Assess for suicidal or homicidal ideation in the severely anxious patient.

- Provide reassurance and appropriate referral to patients with primary exogenous and endogenous anxiety.

- Treatment of anxiety with anxiolytics helps to reduce distress and can help reliably assess the anxious patient.