Table of Contents

- The patient in Undifferentiated Circulatory Shock presents a unique challenge for the emergency physician, as the provider must perform time-critical resuscitation with limited diagnostic information.

- In addition to a focused assessment of the ABC’s during resuscitation, special attention should be paid to “the pump,” “the tank,” and “the pipes” to provide a systematic approach to the hypotensive patient.

- Early recognition of the etiology of hypotension and timely intervention can prevent significant morbidity and mortality, as untreated shock is almost always a fatal diagnosis.

Definition of Shock

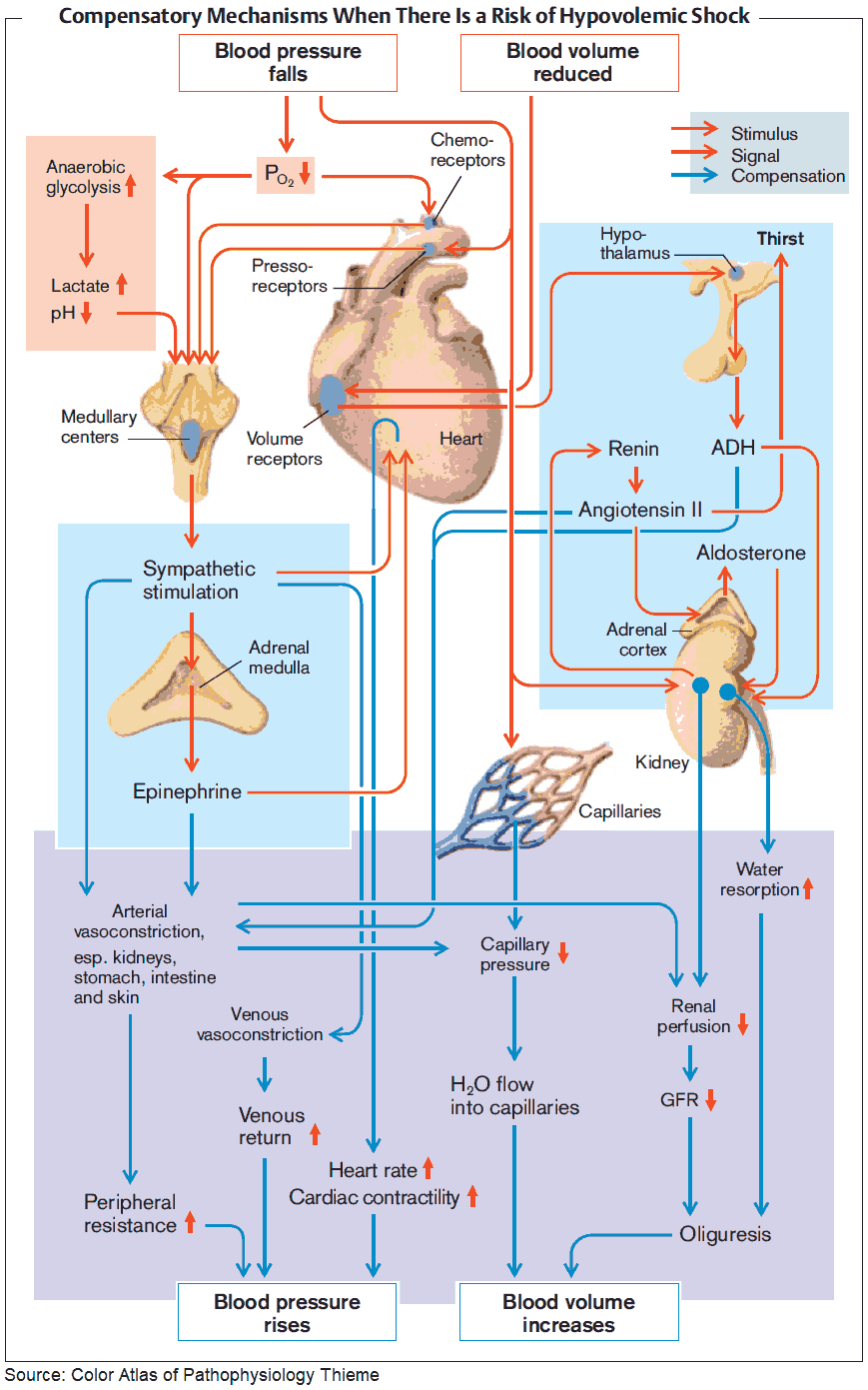

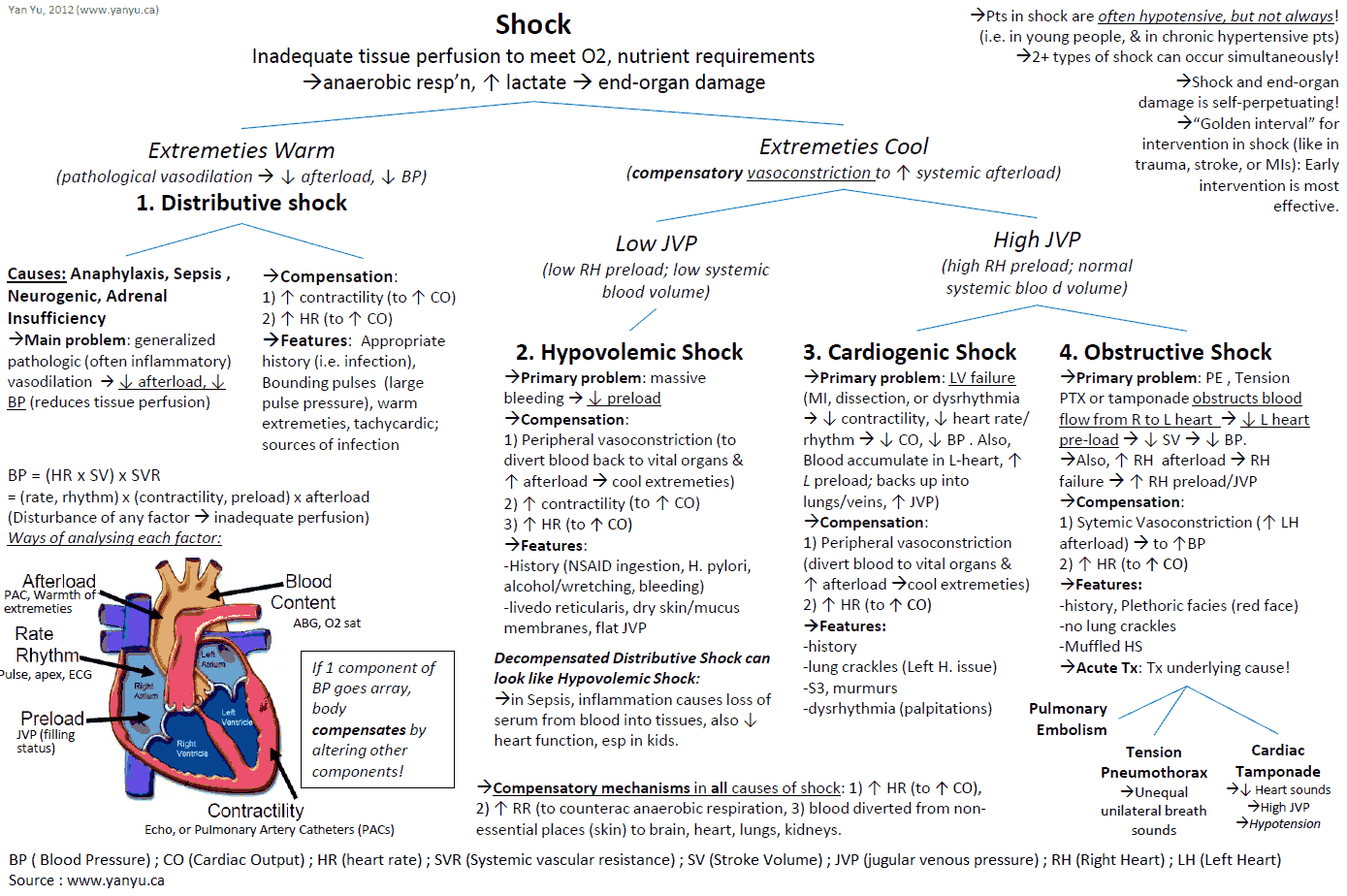

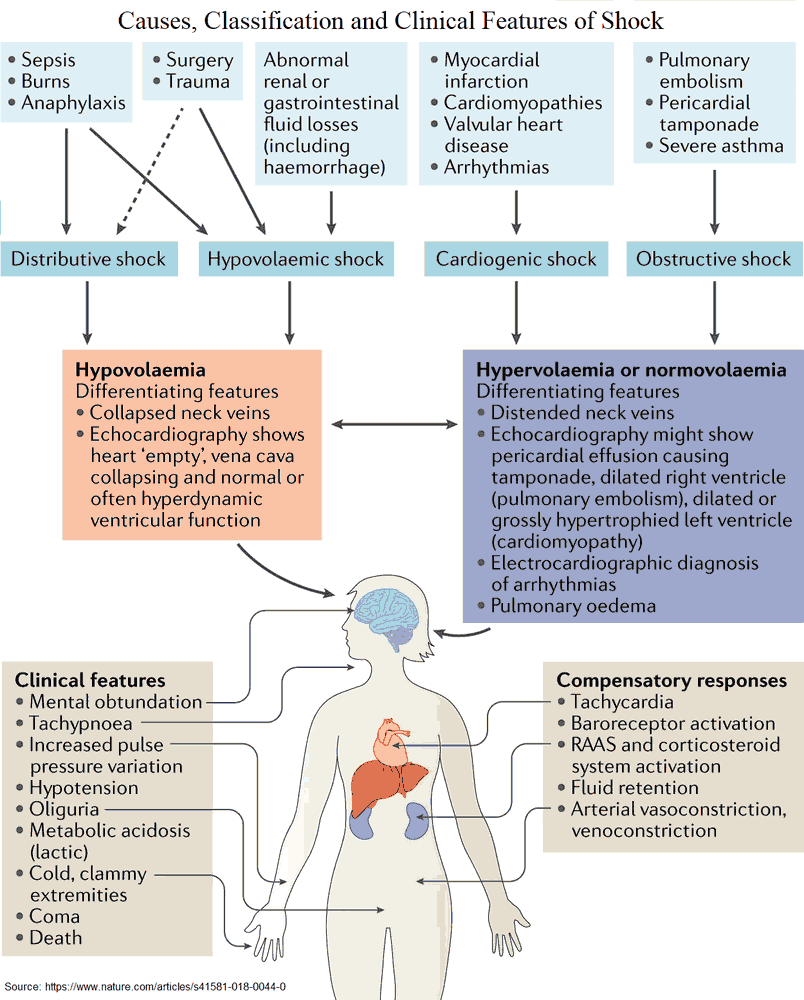

Shock is broadly defined as an imbalance in tissue oxygen demand and tissue oxygen supply. This imbalance results in cellular injury with toxic increases in intracellular calcium, anaerobic respiration, lactate production, cellular death, and the release of systemic proinflammatory cytokines. This cascade ultimately results in end-organ damage and may progress to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.

Types of Shock

The four broad classifications of shock are:

- Hypovolemic

- Cardiogenic

- Obstructive

- Distributive

- Hypovolemic shock may be due to hemorrhage in the setting of trauma or due to fluid losses from severe vomiting or diarrhea.

- Cardiogenic shock results from decreased cardiac output due to an intrinsic heart defect, often from myocardial infarction, valvular rupture, or congestive heart failure.

- Obstructive shock results from a physical obstruction that reduces cardiac output, and may occur due to cardiac tamponade, massive pulmonary embolism, or tension pneumothorax.

- Distributive shock is most commonly due to sepsis and overwhelming infection, though it may also be caused by anaphylaxis or neurogenic shock in spinal cord injury.

The early identification of the type of shock can often be elicited through patient history, physical exam, laboratory investigations, ECG findings, chest x-ray, and bedside ultrasound.

Shock Resuscitation

The initial step in the resuscitation of the patient in undifferentiated shock includes obtaining peripheral venous access and ensuring adequate ventilation and oxygenation. This may involve endotracheal intubation, as the failure of mask ventilation or positive pressure ventilation in the hypotensive patient may result in respiratory failure and circulatory collapse.

A trial bolus of crystalloid solution should be considered, as even those patients in acute cardiogenic shock may be intravascularly depleted.

Careful monitoring of clinical response to fluid should be maintained, as pulmonary edema can be an unintended consequence of fluid administration.

“The Pump” (The Heart)

- An early focus on “the pump” helps discriminate between the four broad classifications of shock and decreases time to lifesaving interventions.

- An ECG should be performed early to assess for STEMI as a cause of cardiogenic shock that necessitates immediate percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). ECG may also demonstrate right heart strain suggesting massive pulmonary embolism or electrical alternans suggesting cardiac tamponade.

- Bedside cardiac ultrasound quickly demonstrates the presence of pericardial effusion and provides an assessment of cardiac contractility. The presence of a large pericardial effusion with right ventricular collapse suggests cardiac tamponade causing obstructive shock, and immediate pericardiocentesis is indicated to aid diastolic filling.

- An acutely dilated right ventricle may suggest massive pulmonary embolism causing right heart strain and obstructive shock.

- A hyperdynamic heart with normal or high contractility suggests distributive or hypovolemic shock.

- A hypodynamic heart with decreased contractility and dilated cardiac chambers suggests cardiogenic shock.

“The Tank” (intravascular volume)

- Following evaluation of “the pump,” an assessment of “the tank” helps determine intravascular volume status and fluid responsiveness.

- Physical exam findings may provide clues as to whether “the tank” is empty or full. Elevated jugular venous pressure, bilateral rales on lung auscultation, or lower extremity edema suggest fluid overload but may not be entirely representative of intravascular volume. A passive leg raise may be performed to temporarily increase venous return and determine fluid responsiveness.

- Bedside ultrasound provides valuable clues regarding a patient’s intravascular status. An inferior vena cava width < 2 cm, as measured 2 to 3 cm distal from the right atrial junction, with inspiratory collapse of >50% suggests the patient is intravascularly depleted and may benefit from intravenous fluids. This finding is also suggestive of hypovolemic or distributive shock. As a caveat, IVC evaluation must be performed prior to intubation as positive pressure ventilation makes IVC assessment unreliable.

- Further evaluation of “the tank” for intraperitoneal free fluid and pleural fluid may suggest hemorrhage as a cause of hypovolemic shock.

- Ultrasound may be used to reassess intravascular status after fluid resuscitation. Vasopressors may be necessary should a patient continue to be hypotensive despite adequate fluid repletion.

“The Pipes” (vessels)

- Finally, evaluation of “the pipes” should be considered in the patient with undifferentiated shock.

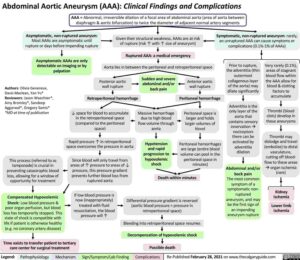

- Physical exam may reveal a pulsatile abdominal mass suggestive of aortic aneurysm, though this finding is not sensitive.

- Bedside ultrasound may be used to evaluate the abdominal aorta for aneurysm or dissection, and in the setting of hypotension a ruptured AAA must be considered.

- Ultrasound of “the pipes” of the lower extremities may be performed to assess for deep vein thrombosis, which may suggest massive pulmonary embolism and obstructive shock.

Key Points

- Remember the four classifications of shock: hypovolemic, distributive, cardiogenic, and obstructive.

- Use a systematic approach to “the pump,” “the tank,” and “the pipes” to determine classification of shock.

- Integrate the use of bedside ultrasound into resuscitation of patients with undifferentiated shock to help make the diagnosis and guide interventions.