Approximately 1% to 2% of patients with hypertension will present with a hypertensive emergency, defined as organ dysfunction due to an elevated blood pressure. Importantly, there is no specific blood pressure threshold that identifies a patient with a hypertensive emergency.

Pathophysiology of Hypertensive Emergency

In a hypertensive emergency, the initial pathophysiologic event is an abrupt increase in systemic vascular resistance (SVR). The abrupt increase in SVR causes endothelial injury and results in increased vascular permeability, platelet activation, and fibrin deposition. This fibrin deposition causes microvascular thrombi, vessel occlusion, organ ischemia, and ultimately organ dysfunction.

Blood Pressure Target/Goals in Hypertensive Emergency

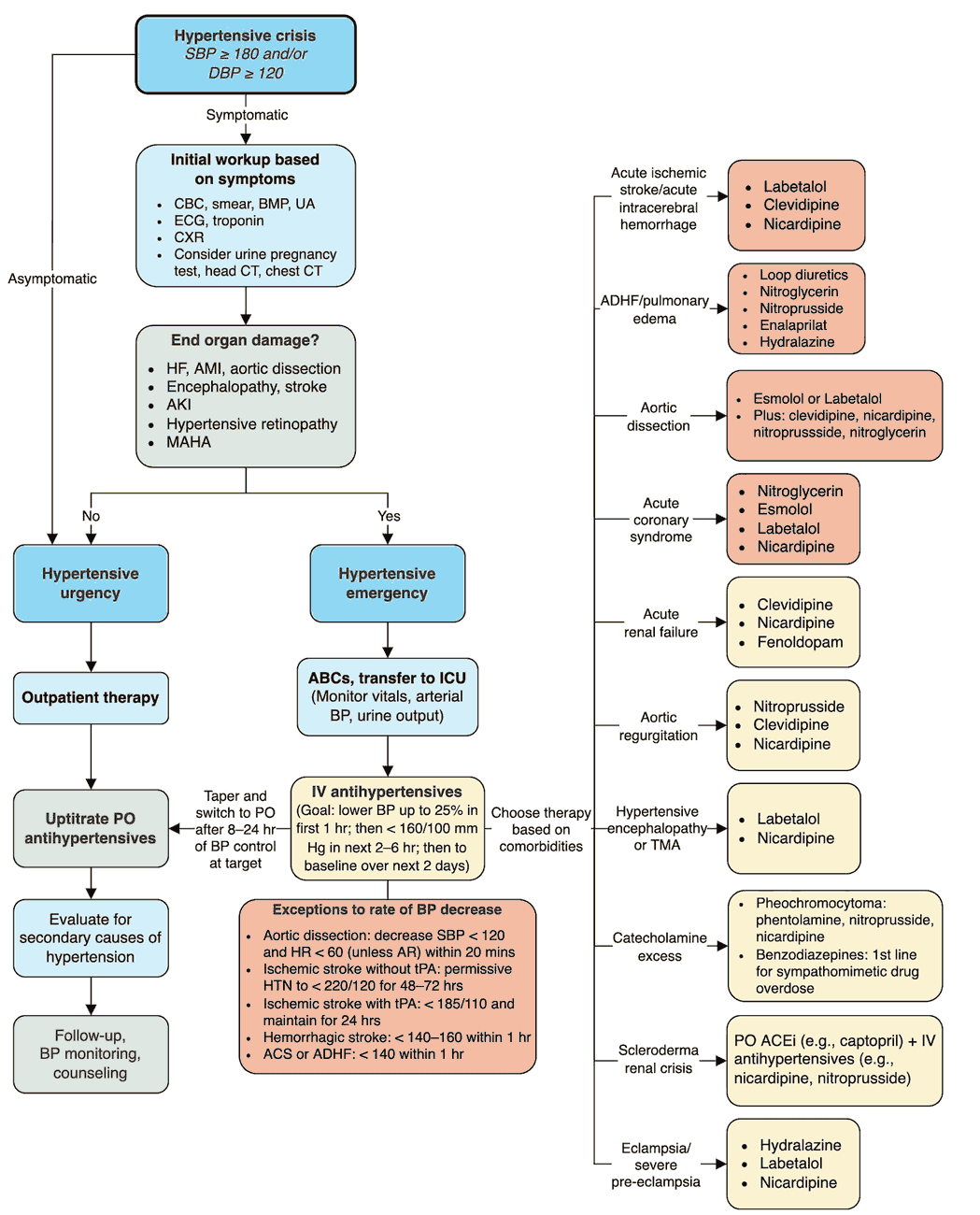

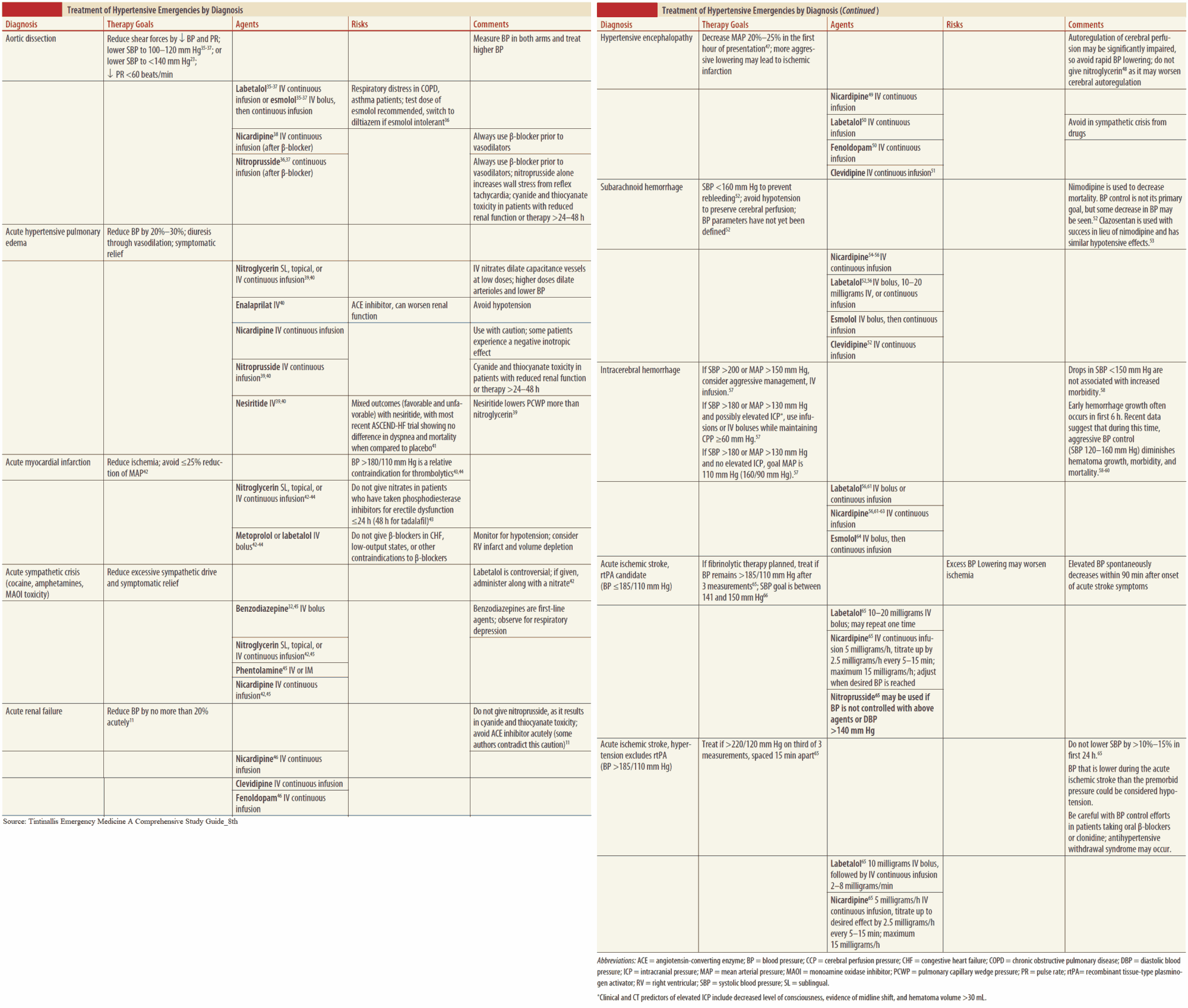

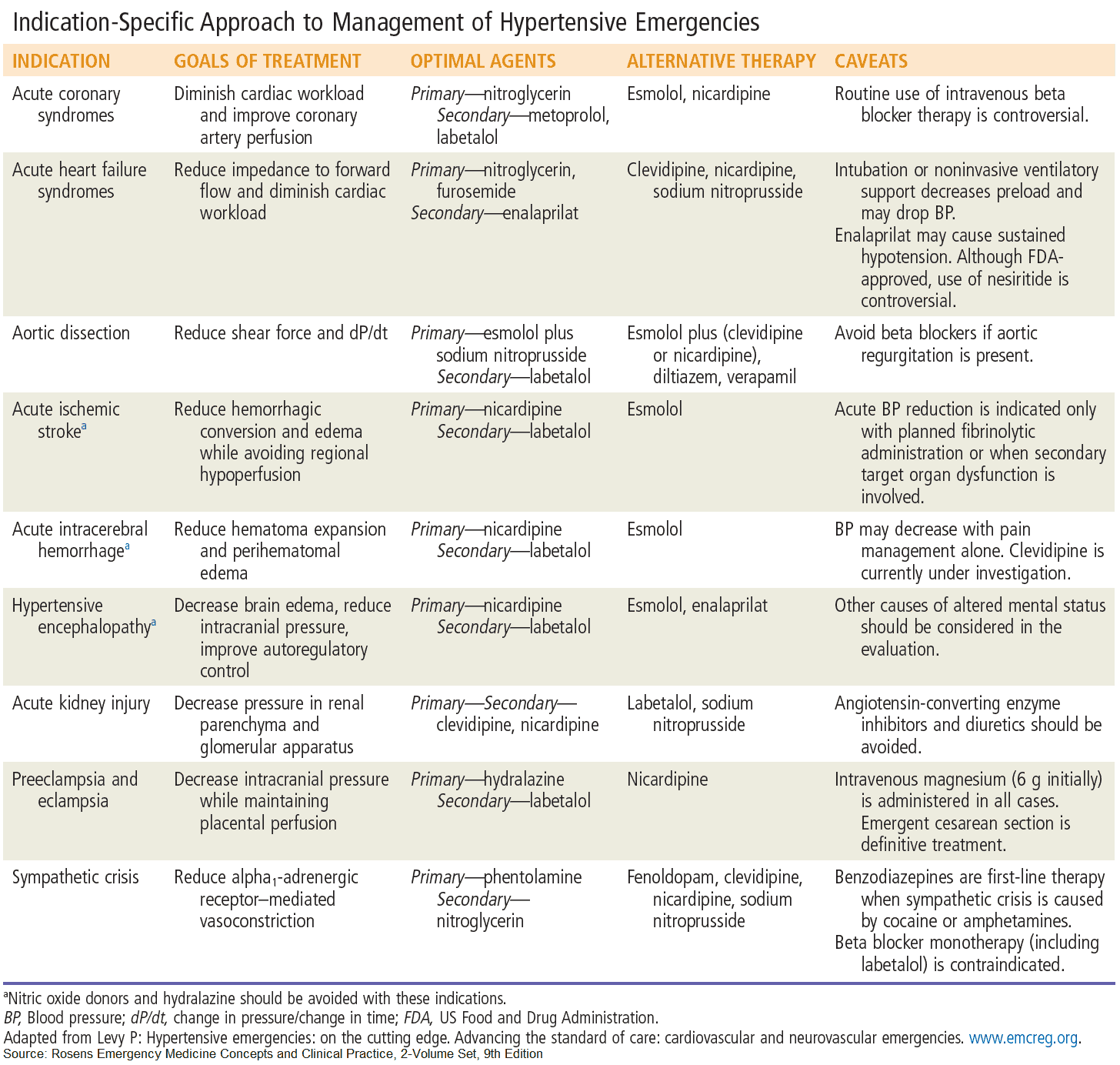

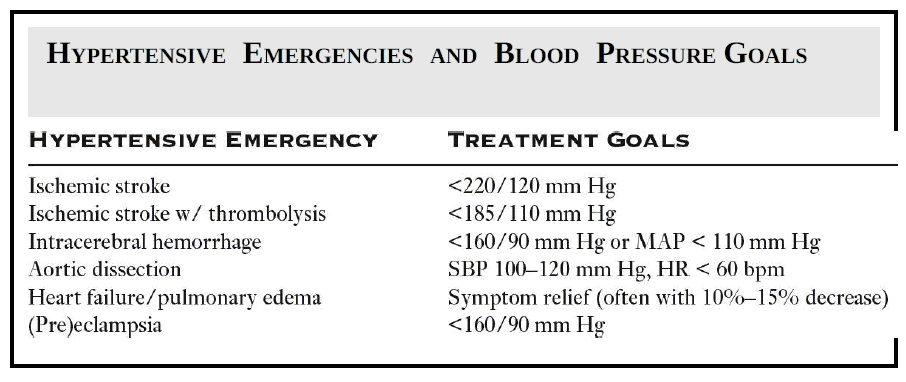

Appropriate reduction in blood pressure is central to the management of a hypertensive emergency. The target reduction in blood pressure depends on the disease process and the specific organ involved.

An abrupt and aggressive reduction in blood pressure can cause further injury and ischemia, as blood pressure can drop below the patient’s autoregulatory threshold.

Current literature recommends that the mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) be lowered no more than 25% in the first 1 to 2 hours from the time of diagnosis.

Conditions that require more aggressive MAP reduction in a shorter time period include:

- Aortic dissection

- Intracerebral hemorrhage

- Eclampsia

For these conditions, it may be necessary to reduce MAP more than 25% in the first 2 hours in order to minimize progressive organ injury.

In contrast, it may be preferable to avoid blood pressure reduction altogether for the patient with an acute ischemic stroke, except in those patients with severe hypertension (>220/110 mm Hg) or those receiving thrombolysis (>185/110 mm Hg). For patients with acute myocardial infarction or acute pulmonary edema, MAP is reduced until clinical symptoms improve.

Treatment of Hypertensive Emergency

Patients with a hypertensive emergency should be treated with an intravenous vasodilator medication. While patients with asymptomatic hypertension can be safely treated with oral medications to slowly reduce blood pressure.

Patients with organ dysfunction due to elevated blood pressure should be given an easily titratable intravenous medication. This allows for a safe, controlled, and appropriate reduction in blood pressure in order to halt organ dysfunction.

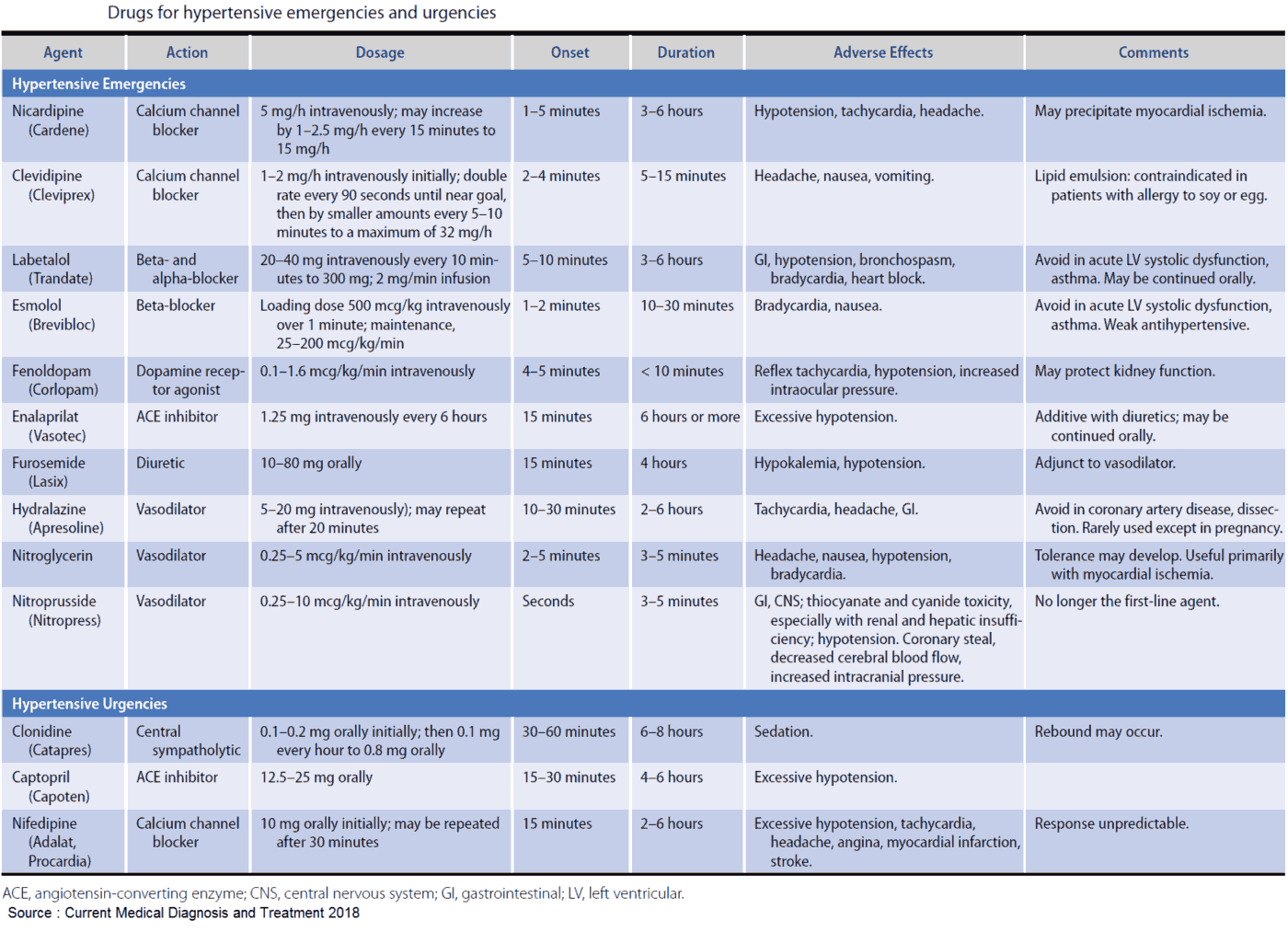

There is currently limited data on the medications used to treat patients with a hypertensive emergency. Medications are best chosen according to the disease process. The most commonly used medications include calcium channel blockers (e.g., nicardipine) and beta-blockers (e.g., labetalol).

- Nicardipine is a second-generation calcium channel blocker that results in coronary and cerebral vasodilation. Nicardipine is commonly used to treat patients with a neurologic emergency, as it has little effect on intracranial pressure.

- Sodium nitroprusside is an arterial and venous vasodilator that can cause a coronary and cerebral “steal” phenomenon. Nitroprusside should thus be avoided in patients with ischemic stroke or acute myocardial infarction. Nitroprusside is also best avoided in patients with eclampsia, as its by-product (cyanide) can accumulate with prolonged use and may cause harm to the fetus.

- Beta-blockers (e.g., esmolol) should be the first-line treatment for patients with an aortic dissection to reduce heart rate. Once the target heart rate is reached, another vasodilator (e.g., nicardipine) can be administered to reduce the systolic blood pressure (SBP) to 100 to 120 mm Hg.

- The direct vasodilator hydralazine should be avoided in patients with a hypertensive emergency, as it can cause a reflex tachycardia and has a duration of action that can exceed 10 hours.

Read More about :

It is important to consider secondary causes of hypertension in the patient with a hypertensive emergency. Secondary causes of hypertension include endocrine conditions (e.g., pheochromocytoma), drugs of abuse (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines, phencyclidine), and medication or drug withdrawal syndromes.

In these conditions, beta-blocker medications should be avoided to prevent a catecholamine surge from unopposed alpha-adrenergic receptor stimulation. The addition of other medications, such as a benzodiazepine or clonidine, may prove beneficial in treating patients with these hyperadrenergic states.

Key Points

- Hypertensive emergency is organ dysfunction due to elevated blood pressure.

- Lower the MAP by no more than 25% in the first 2 hours to avoid hypoperfusion and organ ischemia.

- Tailor your pharmacologic agent to the disease process.

- Avoid reflex tachycardia in aortic dissection by using a beta-blocker first.

- Consider alternative sources for elevated blood pressure (e.g., cocaine, pheochromocytoma).

Suggested Readings

- Baumann B, Cline D, Pimenta E. Review article: Treatment of hypertension in the emergency department. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5:366–377.

- Elliott W. Clinical features in the management of selected hypertensive emergencies. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;48:316–325.

- Muiesan M, Salvetti M, Pedrinelli R, et al. An update on hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. J Cardiovasc Med. 2015;16(5):372–382.

- Singh M. Hypertensive crisis-pathophysiology, initial evaluation, and management. J Indian Coll Cardiol. 2011;1:36–39.

- Vadhera R, Simon M. Hypertensive emergencies in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57: 797–805.