Read Also : Glucocorticoid Therapy – Principal and Adverse Effects

Effect of glucocorticoid administration on adrenocortical cortisol production

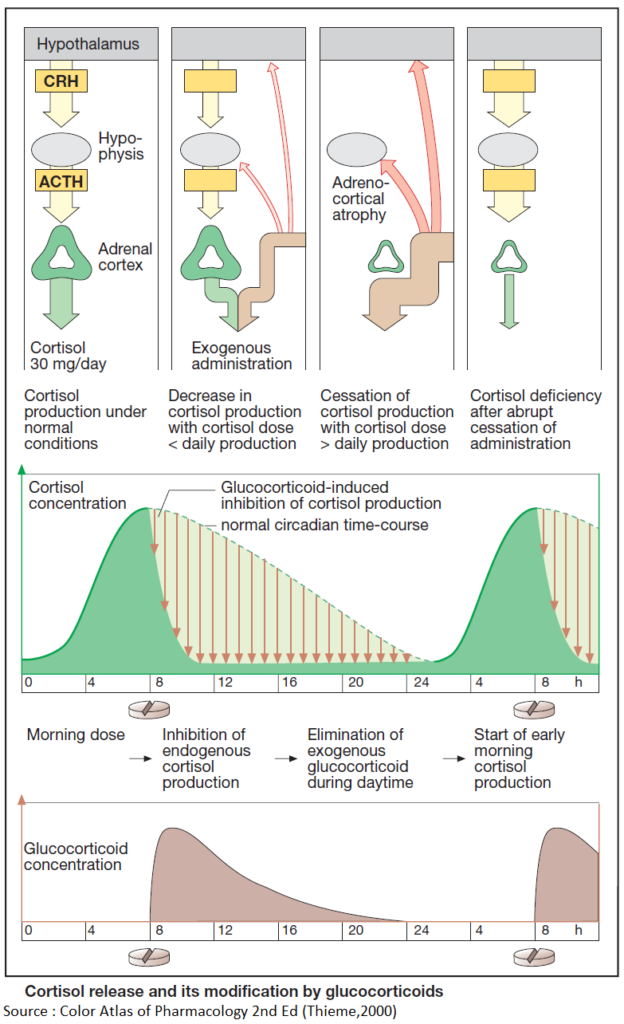

Release of cortisol depends on stimulation by hypophyseal ACTH, which in turn is controlled by hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH).

In both the hypophysis and hypothalamus there are cortisol receptors through which cortisol can exert a feedback inhibition of ACTH or CRH release. By means of these cortisol “sensors,” the regulatory centers can monitor whether the actual blood level of the hormone corresponds to the “set-point.”

If the blood level exceeds the set-point, ACTH output is decreased and, thus, also the cortisol production. In this way cortisol level is maintained within the required range.

The regulatory centers respond to synthetic glucocorticoids as they do to cortisol. Administration of exogenous cortisol or any other glucocorticoid reduces the amount of endogenous cortisol needed to maintain homeostasis. Release of CRH and ACTH declines (“inhibition of higher centers by exogenous glucocorticoid”) and, thus, cortisol secretion (“adrenocortical suppression”).

After weeks of exposure to unphysiologically high glucocorticoid doses, the cortisol-producing portions of the adrenal cortex shrink (“adrenocortical atrophy”). Aldosterone-synthesizing capacity, however, remains unaffected.

When glucocorticoid medication is suddenly withheld, the atrophic cortex is unable to produce sufficient cortisol and a potentially life-threatening cortisol deficiency may develop. Therefore, glucocorticoid therapy should always be tapered off by gradual reduction of the dosage.

Measures for Attenuating or Preventing Drug-Induced Cushing’s Syndrome

- Use of cortisol derivatives with less (e.g., prednisolone) or negligible mineralocorticoid activity (e.g., triamcinolone, dexamethasone).

- Local application

- Typical adverse effects, however, also occur locally, e.g., skin atrophy or mucosal colonization with candidal fungi. To minimize systemic absorption after inhalation, derivatives should be used that have a high rate of presystemic elimination, such as beclomethasone dipropionate, flunisolide, budesonide, or fluticasone propionate.

- Lowest dosage possible

- For longterm medication, a just sufficient dose should be given. However, in attempting to lower the dose to the minimal effective level, it is necessary to take into account that administration of exogenous glucocorticoids will suppress production of endogenous cortisol due to activation of an inhibitory feedback mechanism. In this manner, a very low dose could be “buffered,” so that unphysiologically high glucocorticoid activity and the anti-inflammatory effect are both prevented.

Regimens for prevention of adrenocortical atrophy

Cortisol secretion is high in the early morning and low in the late evening (circadian rhythm). This fact implies that the regulatory centers continue to release CRH or ACTH in the face of high morning blood levels of cortisol; accordingly, sensitivity to feedback inhibition must be low in the morning, whereas the opposite holds true in the late evening.

- Circadian administration

- The daily dose of glucocorticoid is given in the morning. Endogenous cortisol production will have already begun, the regulatory centers being relatively insensitive to inhibition.

- In the early morning hours of the next day, CRF/- ACTH release and adrenocortical stimulation will resume.

- Alternate-day therapy

- Twice the daily dose is given on alternate mornings. On the “off” day, endogenous cortisol production is allowed to occur.

- The disadvantage of either regimen is a recrudescence of disease symptoms during the glucocorticoid-free interval.

Read Also : Glucocorticoid Therapy – Principal and Adverse Effects