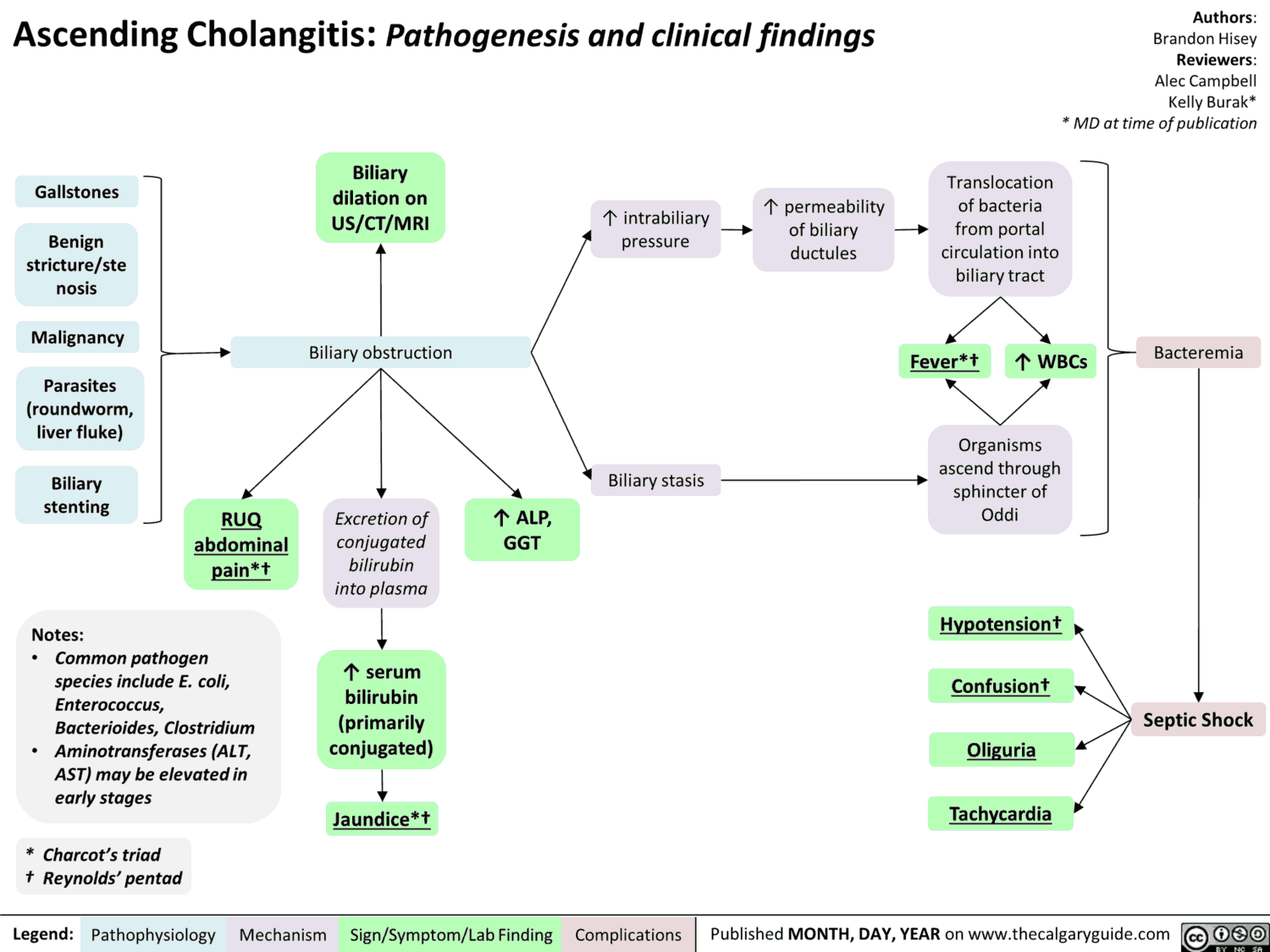

A classic “you’ll miss it if it’s not on your differential,” ascending cholangitis refers to a bacterial infection of the biliary system, requiring both obstruction and bacterial colonization of the biliary tract.

Normally, bile is sterile. Bile salts have bacteriostatic properties, and the sphincter of Oddi controls the direction of bile flow, acting as a barrier between the sterile bile duct and the bacteria-filled duodenum.

Without obstruction of the biliary system, ascending cholangitis does not occur. Even bacterial colonization of the bile in the absence of obstruction does not usually progress to clinical cholangitis.

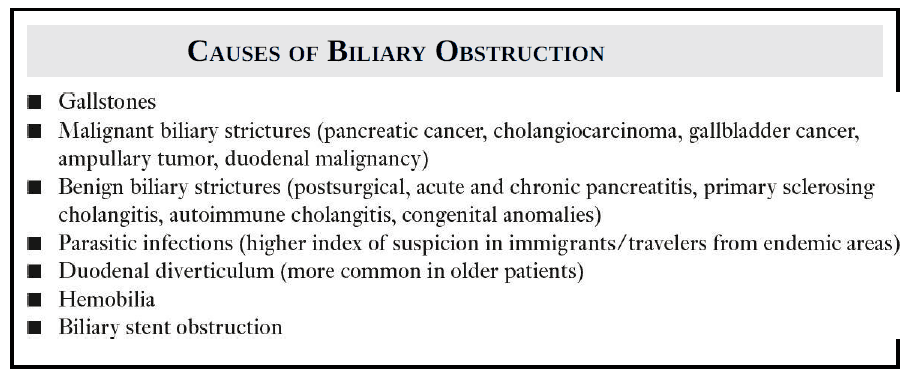

Causes of Biliary Obstruction

How bacteria enter an obstructed biliary system ?

It’s still not always known how bacteria enter an obstructed biliary system, but one clear way is when the doctor does the dirty work by inadvertently interfering with the physiologic barrier between the bile duct and the intestine via surgery, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC).

Bacteria, of which the most common are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, and Bacteroides, can also enter the biliary system from the lymphatics or via portal vein blood. Once the bacteria enter an obstructed bile duct, ascending cholangitis may result.

Who gets ascending cholangitis?

You should think about it in any septic patient who has signs and symptoms of biliary tract disease (often subtle), especially if that patient is diabetic, elderly, or debilitated.

Symptoms of Ascending Cholangitis

Charcot was one of the first physicians to describe cholangitis, or “hepatic fever” as he called it, and he noted a constellation of symptoms that made up Charcot triad:

- Intermittent fever with chills

- Right upper quadrant pain

- Jaundice

Reynolds pentad when you add to the Charcot triad:

- Mental status changes

- Shock

Reynolds pentad confers a much graver prognosis without prompt decompression.

The most frequent symptoms with acute cholangitis are fever and abdominal pain (approximately incidence of 80% in most reports). Clinical jaundice is less frequently seen (~60% to 70%). Severe presentations (e.g., with shock and altered mental status) are fortunately much less common (3.5% to 7.7%).

Cholangitis rarely presents classically, so it is an important consideration in any septic patient without an obvious source. Importantly, the most severe cases are often the most difficult to detect as the patient may be too sick to help the clinician localize the infection of history and physical examination.

Bedside ultrasound examination may be particularly helpful in this scenario as a screen for biliary pathology in the septic patient with altered mental status.

Kids can get ascending cholangitis too!

And don’t forget, kids can get ascending cholangitis too! Kids who have undergone surgical Roux-en-Y procedures (such as the Kasai procedure for biliary atresia) and those with indwelling catheters or failure to thrive are at increased risk.

Differentiating Cholangitis from Cholecystitis

Once you suspect cholangitis, you’ll be tasked with differentiating it from cholecystitis, both of which can present very similarly. An elevated bilirubin is more characteristic of cholangitis. Ultimately, though, ultrasound evidence of dilated common and intrahepatic bile ducts usually is required to distinguish cholangitis from cholecystitis.

Treatment of Ascending Cholangitis

- Hemodynamic stabilization

- Broadspectrum antibiotics

- Admission to a monitored setting (ICU often)

- Biliary tract decompression (surgery, interventional radiology, gastroenterology)

These patients are sick, and if you don’t make the diagnosis, they will not do well!

Key Points

- Consider in any septic patient without another source.

- Think of risk factors leading to obstruction of the biliary system, and include cholangitis in your differential for septic kids too.

- Differentiating cholangitis from cholecystitis: look for elevated bilirubin and ultrasound evidence of biliary duct dilation in cholangitis.

- ERCP can be the cause and the cure!

References / Suggested Readings

- Flemma RJ, Flint LM, Osterhout S, et al. Bacteriologic studies of biliary tract infection. Ann Surg. 1967;166(4):563–572.

- Kiriyama S, Takada T, Strasberg SM, et al. TG13 guidelines for diagnosis and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20(1):24–34.

- Lai EC, Mok FP, Tan ES, et al. Endoscopic biliary drainage for severe acute cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1582–1586.

- Mosler P. Diagnosis and management of acute cholangitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2001;13(2): 66–72.