Table of Contents

The diagnosis and epidemiology of acute calculous cholecystitis have been drilled into us since the early days of medical school. Every review book ever published has the mnemonic: Fat, Fertile, Forty, Family history, and Female. However, the discussion about acalculous cholecystitis has typically been short and inadequately summarized by: “it’s an ICU diagnosis in the critically ill.”

The reporting and description of acalculous cholecystitis has evolved along with the advancement of its care. Duncan initially described it in 1844 in a patient who underwent a femoral hernia repair. Later, there was increased reporting and awareness during the Vietnam War in soldiers surviving sepsis and traumatic injuries.

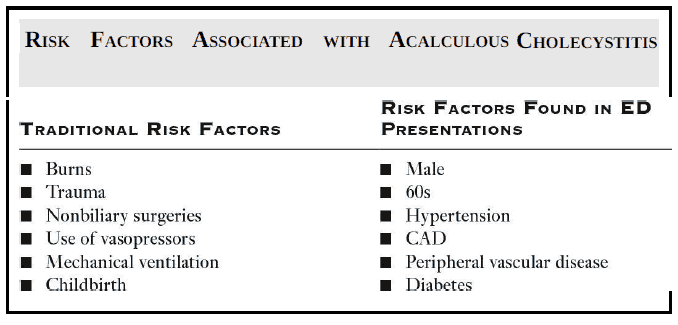

With the rise of intensive care units, the prevalence of acalculous cholecystitis also grew. Now that modern medicine allows patients to live longer with multiple comorbidities, we have even seen this disease in the outpatient setting. The key to diagnosis starts with an awareness of the unique set of risk factors these patients have (see image bellow).

Epidemiology of Acalculous Cholecystitis

Acalculous cholecystitis is a surgical emergency—a good prognosis hinges on early recognition and appropriate surgical treatment. It is estimated that acalculous cholecystitis comprises about 10% of all cholecystitis cases.

In one study, within a 7-year period, 77% of all patients identified with acalculous cholecystitis presented in the outpatient setting. Importantly, 45% of those patients were ultimately admitted without the diagnosis of cholecystitis.

If specific treatment is delayed, this disease has a mortality rate as high as 65%, whereas, with early intervention, mortality is ~7%. Contrast this with commonly reported numbers of 1.5% to 3% mortality for calculous cholecystitis.

Acalculous cholecystitis is a rare entity, but it is important to keep in mind in patients with sepsis due to an unclear source, especially in the setting of abdominal pain.

Pathophysiology of Acalculous Cholecystitis

The pathophysiology of acalculous cholecystitis is thought to start with an acute or acute-on-chronic condition that leads to endothelial injury and gallbladder ischemia.

The lack of perfusion creates stasis in the gallbladder, increased distention, and a localized inflammatory response. Some hypothesize that the bile salts and their by-products are toxic to the gallbladder when stasis occurs.

Once cholecystitis has set in, a secondary bacterial infection can occur, usually with coliforms and anaerobes (commonly Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae). The exact nature and mechanism of the bacterial infection are not fully understood. Nevertheless, antibiotics are still considered a mainstay of treatment.

Clinical Presentation of Acalculous Cholecystitis

The clinical presentation can be varied, but most commonly, it consists of:

- right upper quadrant abdominal pain

- fever

- jaundice

- nausea

- vomiting

- occasionally septic shock

Physical examination may find a palpable right upper quadrant mass and laboratory tests may show leukocytosis and elevated liver enzymes.

Inpatients are more apt to have the major identifying risk factors: burns, trauma, nonbiliary surgeries, use of inotropes, mechanical ventilation, or childbirth.

It is most certainly more difficult to pick these patients out in the outpatient and emergency department (ED) settings.

Acalculous cholecystitis is more common in males (1:1 to 2.8:1 male to female predominance), advanced age (average age is in the 60s), cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, alcoholic liver disease, and COPD. These cases can be complicated by the patient being demented or developmentally delayed, which may prevent an adequate history and physical exam.

In children, acalculous cholecystitis may present as a complication of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection.

Patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) may also present with a nonspecific infectious prodrome and upper abdominal pain with acalculous cholecystitis secondary to an opportunistic infection, though it is more common for these patients to have cholangitis.

Diagnosis of Acalculous Cholecystitis

Diagnostic imaging is critical in making the diagnosis early. One study evaluating computed tomography (CT), ultrasound, and scintigraphy found that ultrasound (sensitivity 92%, specificity 96%) and CT (sensitivity 100%, specificity 100%) were both excellent diagnostic modalities but that scintigraphy suffered from poor specificity (38%).

Often, at the time of diagnosis, the differential remains broad and a CT scan may offer further diagnostic assessment for other possibilities on the differential.

Treatment of Acalculous Cholecystitis

On a positive note, once the diagnosis is made, the treatment remains similar to that of calculous cholecystitis.

Antibiotics should be initiated to cover coliforms and anaerobes, typically a beta-lactam with a beta-lactamase inhibitor.

Surgical consultation is necessary to decide whether the patient should be taken to the operating room for cholecystectomy versus an interventional radiology–guided cholecystostomy. This decision usually revolves around the patient’s comorbidities and perioperative risk.

Complications such as emphysematous cholecystitis and perforated gallbladder can drastically alter the patient’s course and treatment plan, further reinforcing the importance of early diagnosis in the ED.

Key Points

- Not all cholecystitis is caused by gallstones.

- Many patients with acalculous cholecystitis may present from the outpatient setting.

- Once the diagnosis is made, initiate broad-spectrum antibiotics and obtain early surgical consultation.

References / Suggested Readings

- Savoca PE, Longo WE, Zucker KA, et al. The increasing prevalence of acalculous cholecystitis in outpatients. Results of a 7-year study. Ann Surg. 1990;211:433.

- Wang AJ, Wang TE, Lin CC, et al. Clinical predictors of severe gallbladder complications in acute acalculous cholecystitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2821.

- Yi DY, Kim JY, Yang HR. Ultrasonographic gallbladder abnormality of primary Epstein–Barr virus infection in children and its influence on clinical outcome. Celis MJC, ed. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(27):e1120.

- Mirvis SE, Vainright JR, Nelson AW, et al. The diagnosis of acute acalculous cholecystitis: A comparison of sonography, scintigraphy, and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:1171.