Table of Contents

Loss of consciousness may be transient (syncope) or ongoing (coma). Many patients are admitted to hospital with “collapse”. Patients use the word “collapse” to describe a variety of situations, and it is essential to determine whether or not the patient has actually lost consciousness.

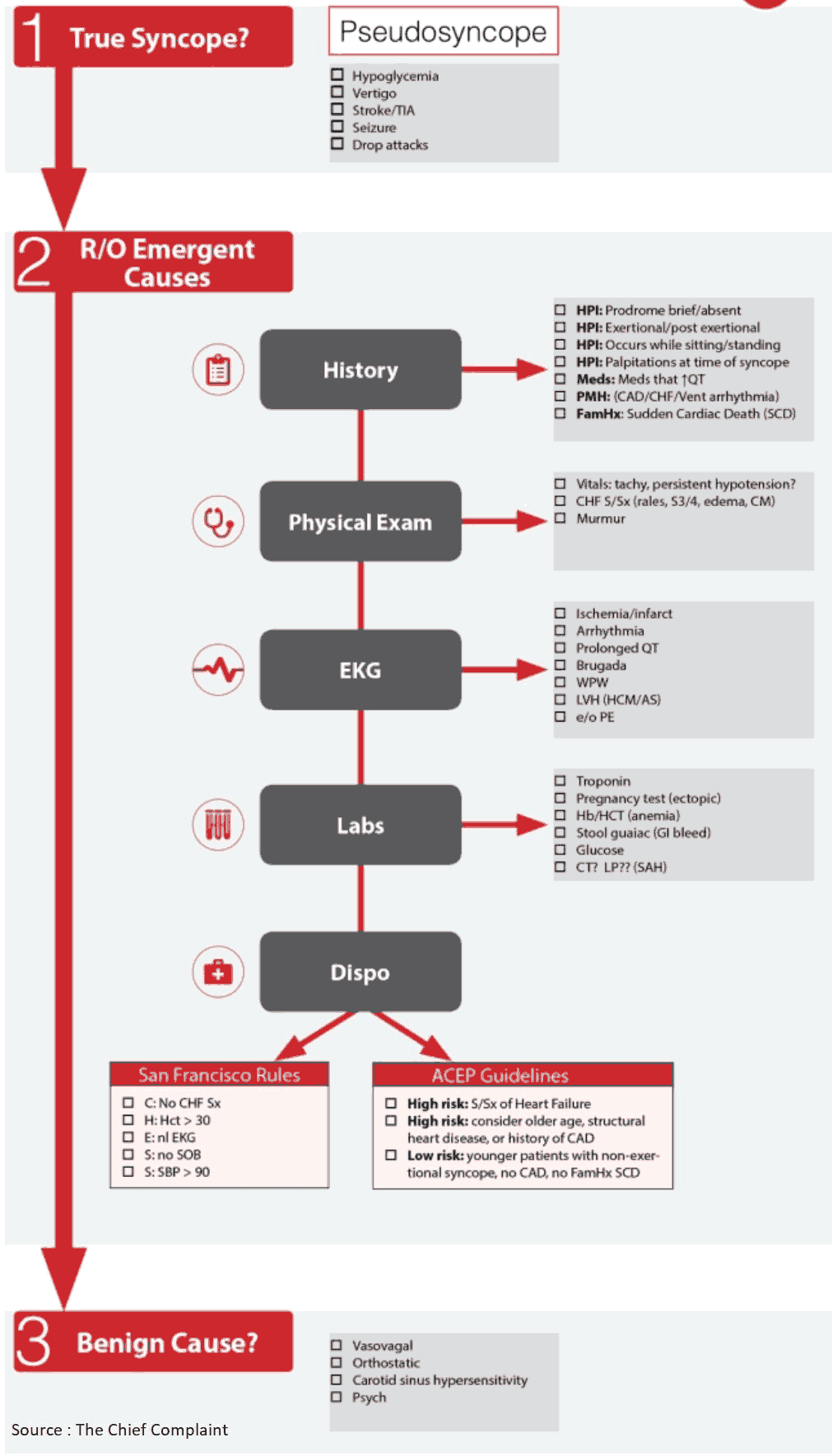

Causes and Differential Diagnosis of Loss of Consciousness

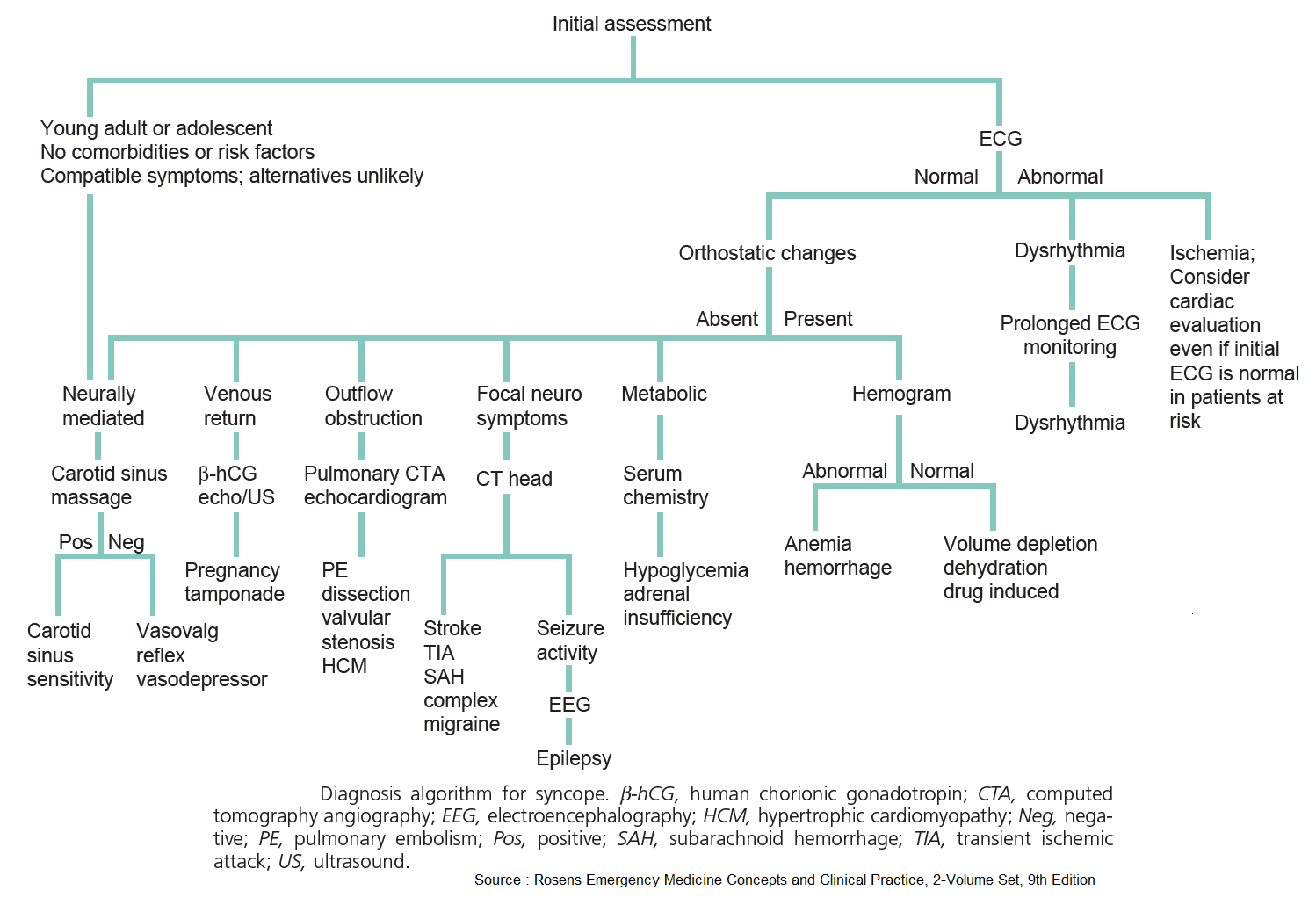

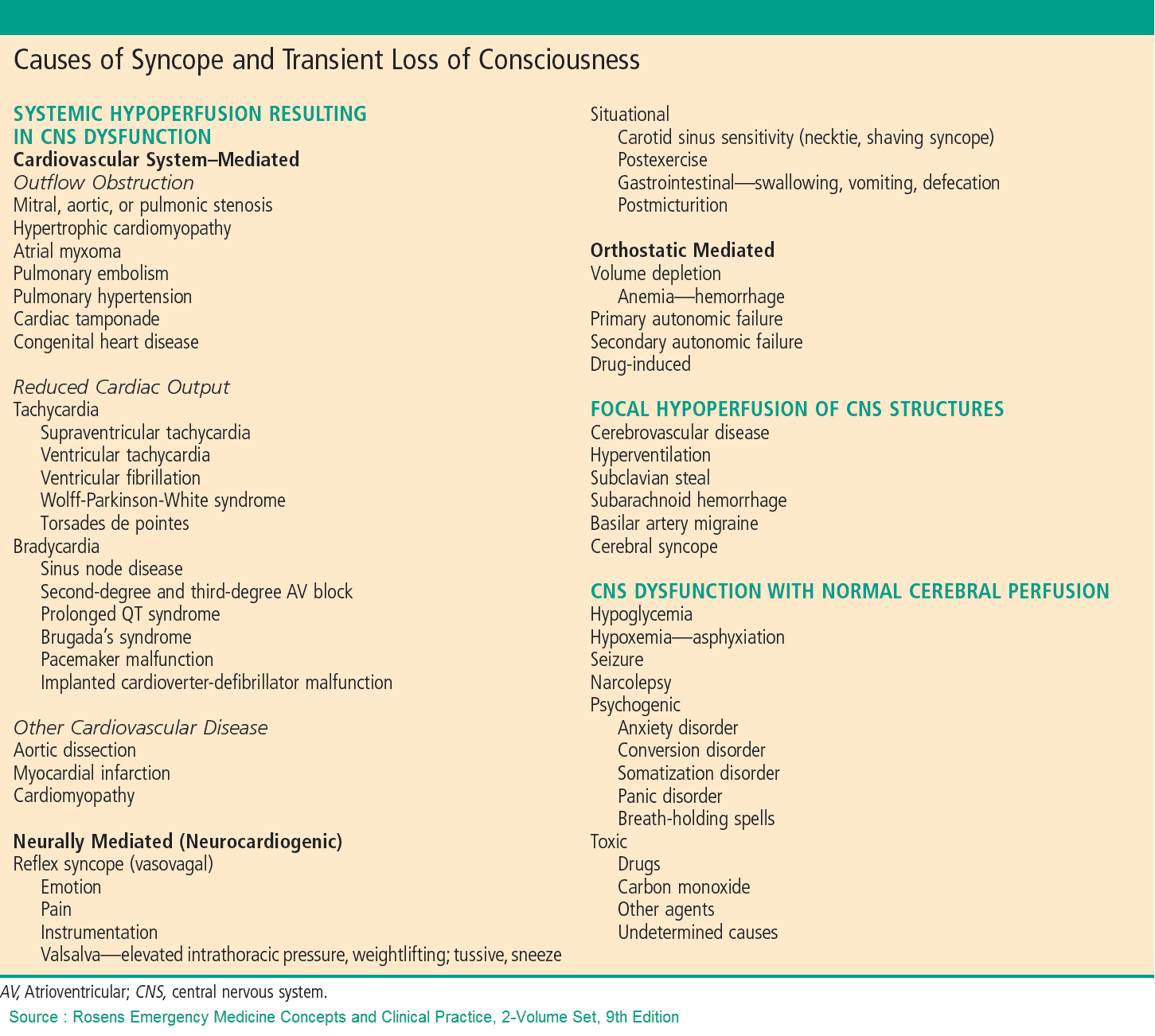

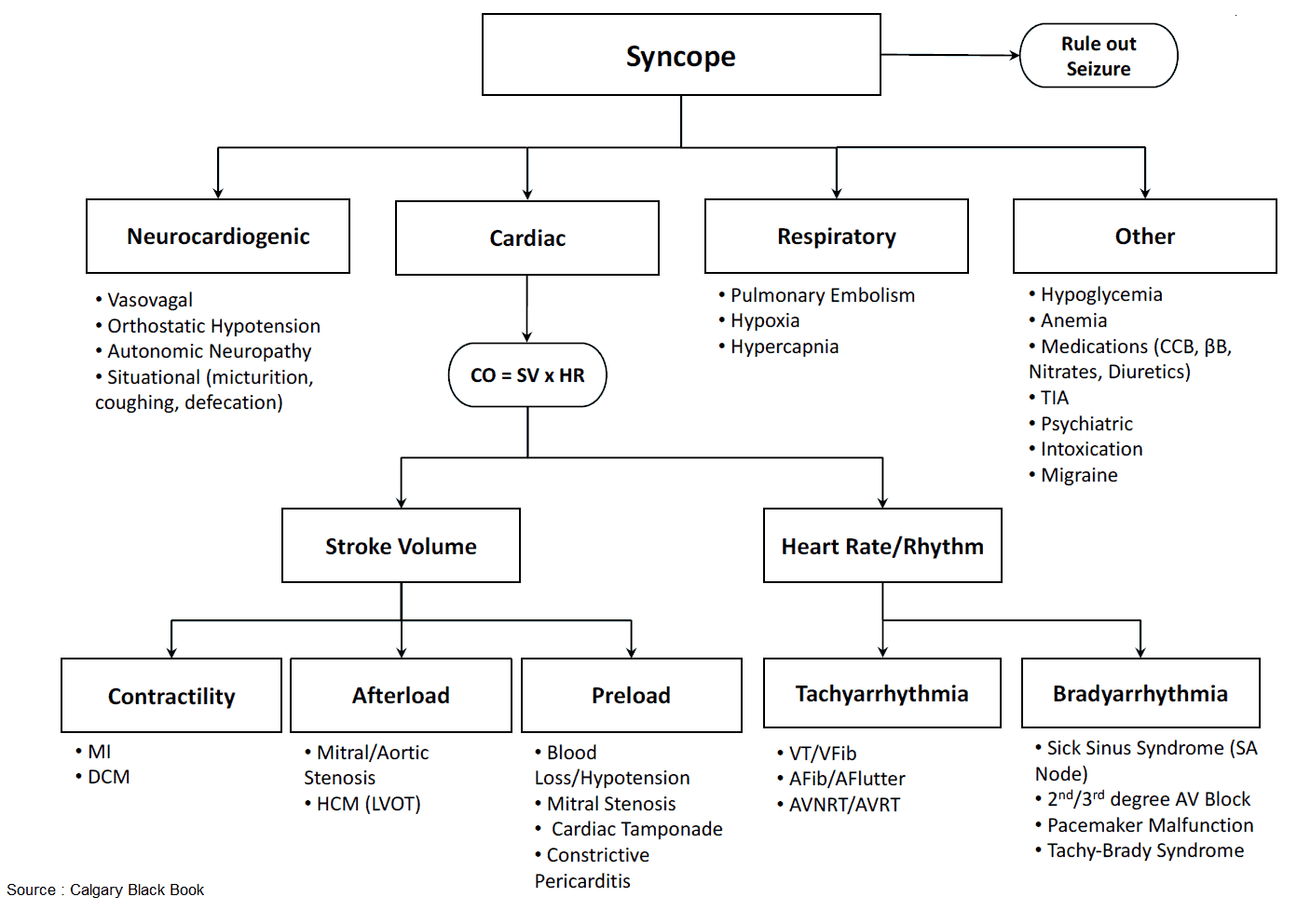

Syncope (“blackout”)

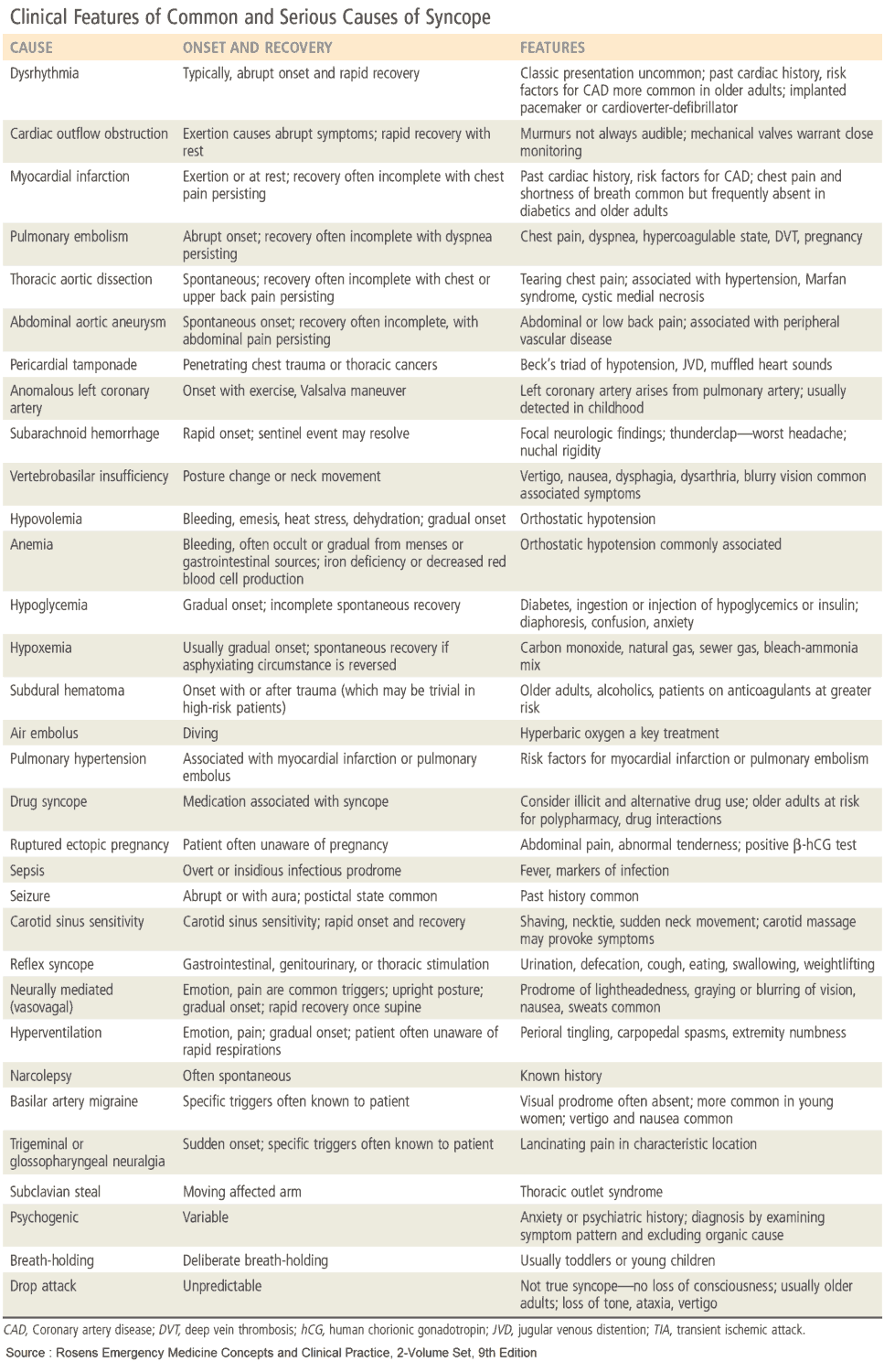

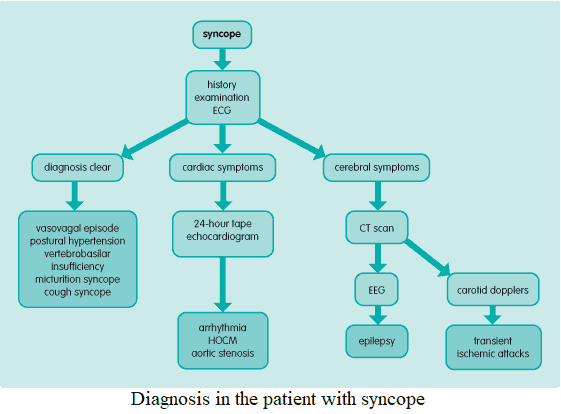

Syncope is caused by a transient loss of consciousness and motor tone due to a reduction in cerebral perfusion. There is spontaneous recovery, and it is often recurrent. Causes and forms of syncope include:

- Vasovagal attack: simple faint.

- Postural hypotension (orthostatic hypotension): may be caused by drugs, alcohol, aging, or hypovolemia.

- Vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

- Cardiac: Stokes-Adams attacks, arrhythmias, hypertrophy obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM), aortic stenosis.

- Transient ischemic attacks (TIA): posterior cerebral circulation.

- Micturition syncope.

- Cough syncope.

- Carotid sinus syncope: increased carotid sinus sensitivity in the elderly due to atherosclerosis.

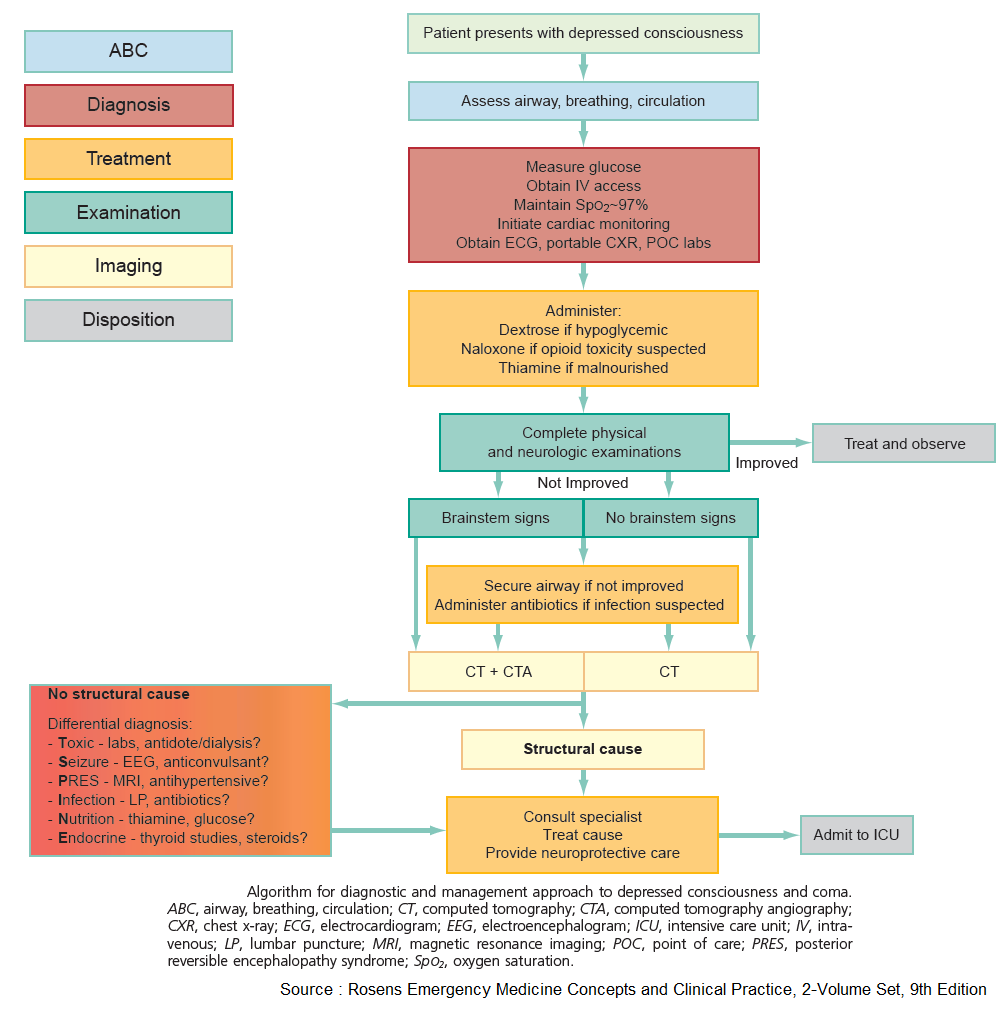

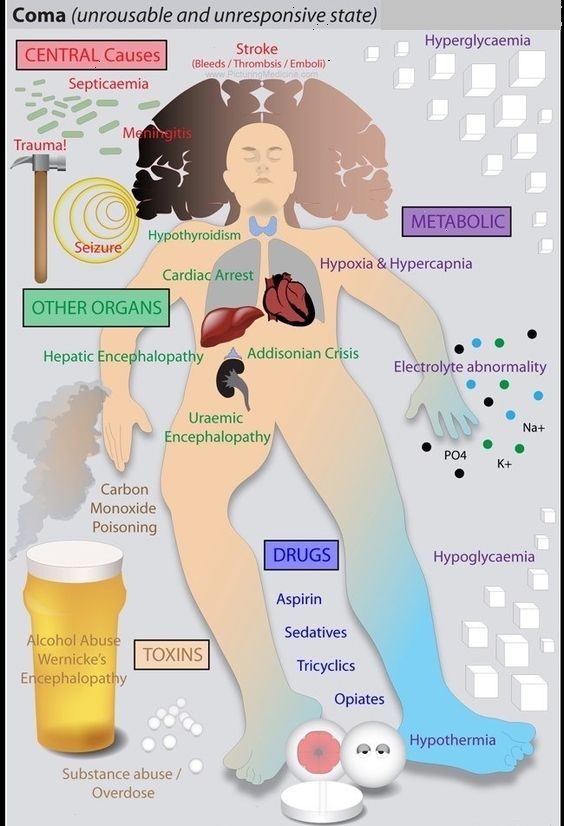

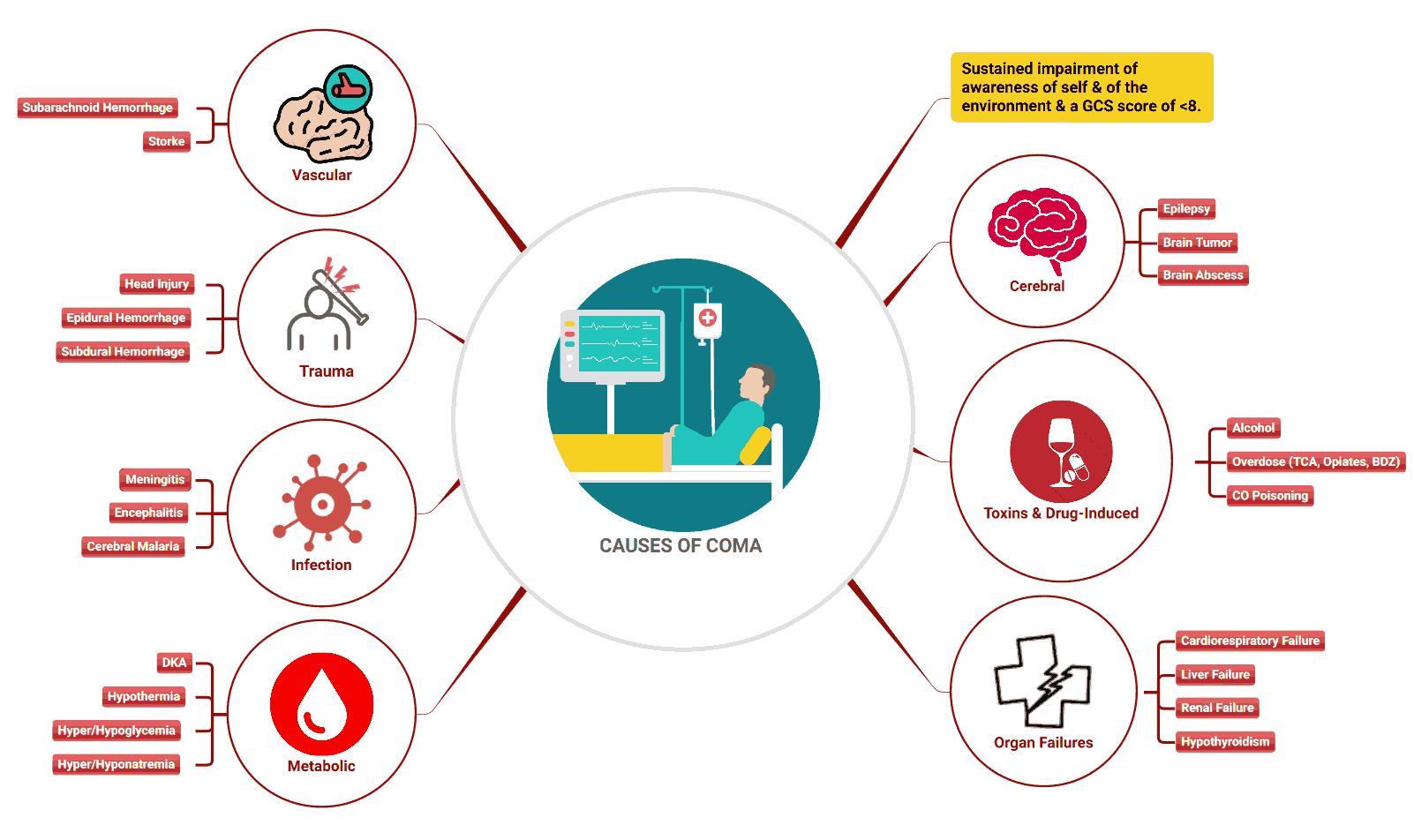

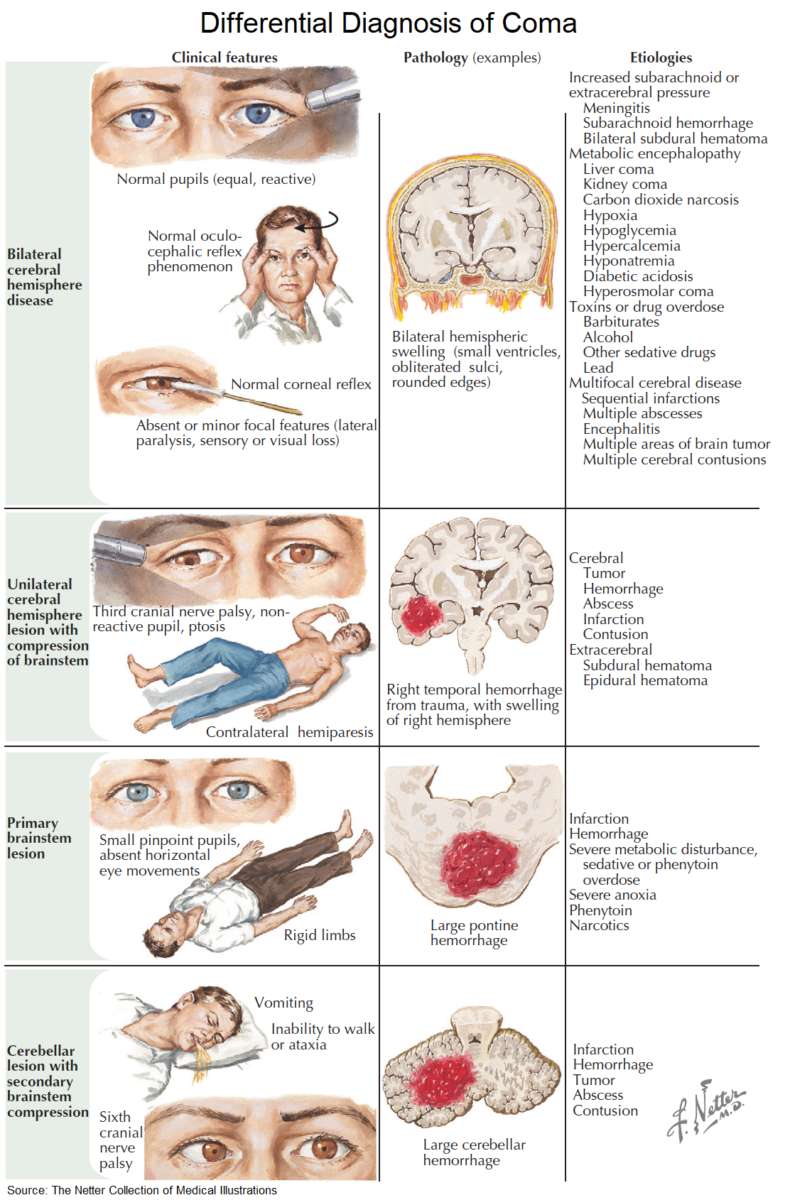

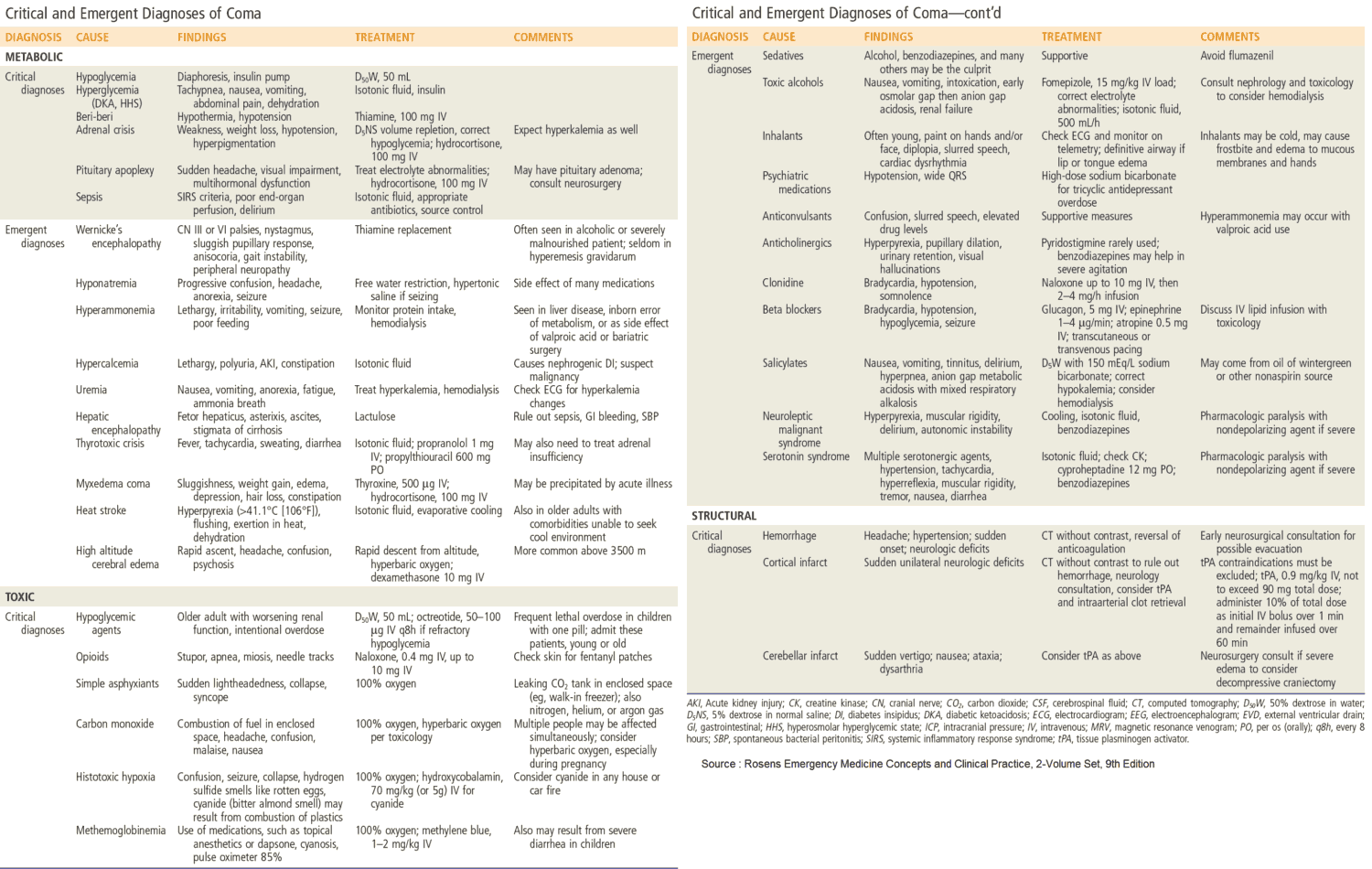

Coma

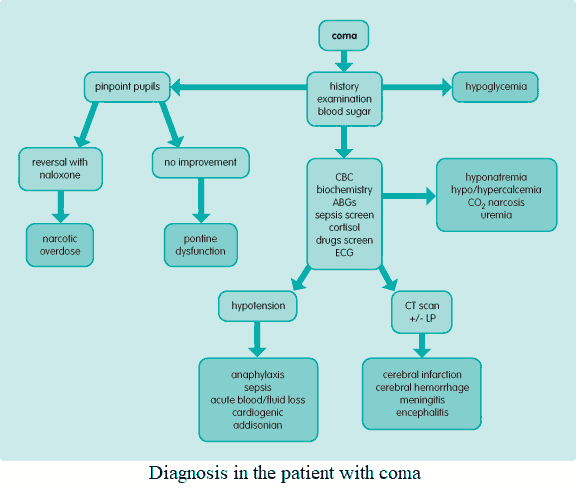

In coma, the patient remains unconscious and is unarousable. Coma can be caused by the following:

- Vascular: intracranial hemorrhage, cerebral infarction.

- Epilepsy: status epilepticus.

- Shock: anaphylaxis, sepsis, acute blood or fluid loss, cardiogenic, addisonian.

- Drugs overdose: narcotics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines.

- Alcohol: acute intoxication.

- Metabolic: hypoglycemia, hepatic encephalopathy, uremia, porphyria.

- Trauma, particularly closed head injury.

- Infection: meningitis, encephalitis, malaria.

- Respiratory: hypercapnia.

- Electrolyte: hyponatremia, hyper- or hypocalcemia.

- Endocrine: hypopituitarism, hypothyroidism.

History in the Patient with Loss of Consciousness

When a patient presents in coma, relatives or the PCP should be contacted to gain information regarding previous medical history, prodromal illness, known alcohol or drug abuse, and whether the events leading to the coma were witnessed by anyone.

In syncope, the history should focus on the following details:

Presyncope

- What was the patient doing at the time?

- Were there any symptoms before the patient lost consciousness?

- In postural hypotension the patient may have stood up suddenly.

- If the patient had just turned his or her head, consider vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

- Prior to an epileptic fit, there is often an aura.

- In arrhythmia, the patient can be aware of palpitations, chest pain, or dyspnea before blacking out.

- In Stokes-Adams attacks there is usually no warning.

- Exertional syncope is seen in aortic stenosis and HOCM.

- Occasionally, cough or micturition may cause syncope.

The attack itself

- What happened during the episode itself? This is where the history of a witness is vitally important.

- Seizures associated with tongue biting and urinary incontinence indicate epilepsy. (Note that if a patient remains propped upright in other forms of syncope, a secondary seizure may occur).

- In Stokes-Adams attacks the patient is typically seen to go deathly pale with flushing on recovery. The length of time that the patient remained unconscious should be recorded. Note, however, that patients may begin to twitch or have some seizure-like activity during a Stokes-Adams attack secondary to cerebral anorexia. Look for a history of seizures vs. a history of MI, CHF, etc., to help differentiate between these two causes of syncope.

Postsyncope

- How quickly did the patient recover?

- Was there any injury? Syncope is generally followed by rapid recovery. However, in epilepsy, there is usually postictal sleepiness.

- It is also very important to ask whether patients hurt themselves during the episode. If there is significant injury consider cardiac syncope (lack of warning).

Risk Factors

- Is there a previous history of epilepsy, cardiac disease, cerebrovascular disease, or obstructive airways disease?

- Is the patient a diabetic on insulin?

- Is the patient a health-care worker with access to insulin?

- Is there a history of drug abuse or depression?

- Has there been recent travel to a malarial area?

- Has there been any trauma to the head?

Always try to obtain a history from a witness, even if the patient has regained consciousness.

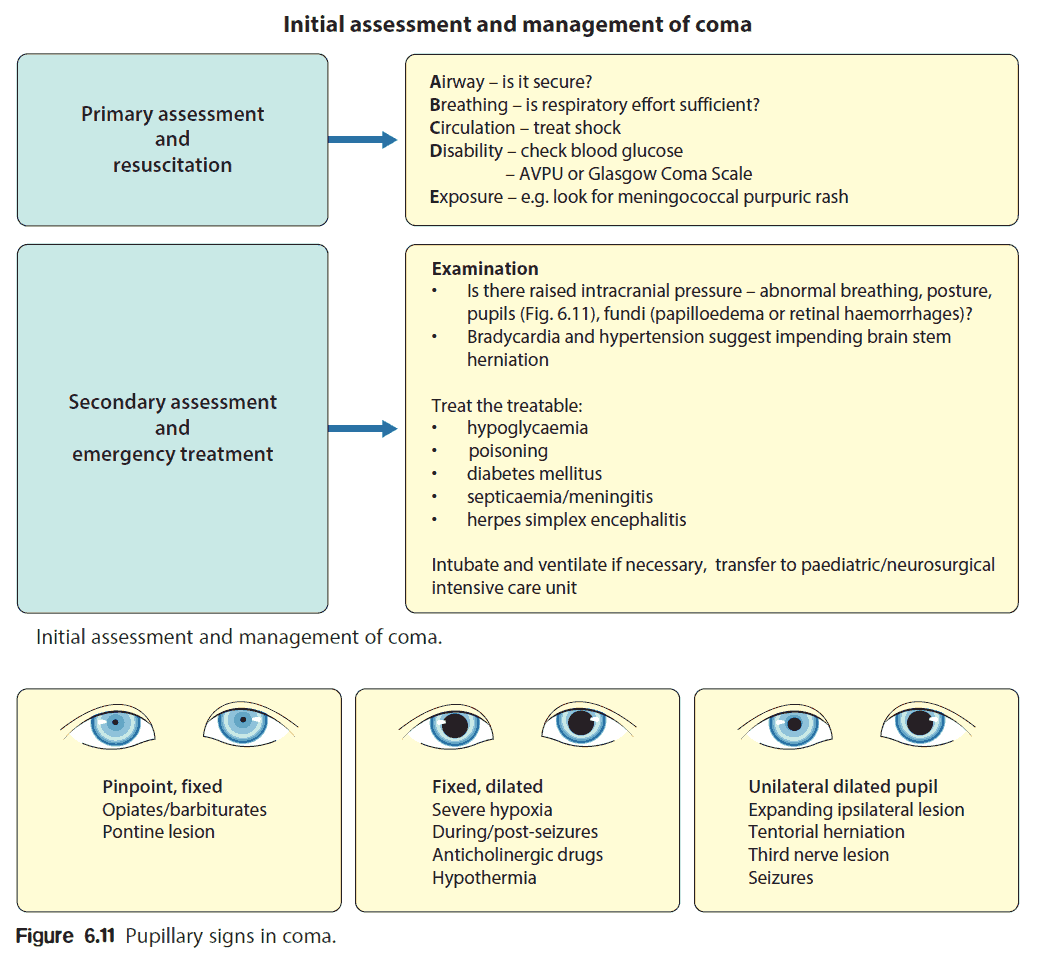

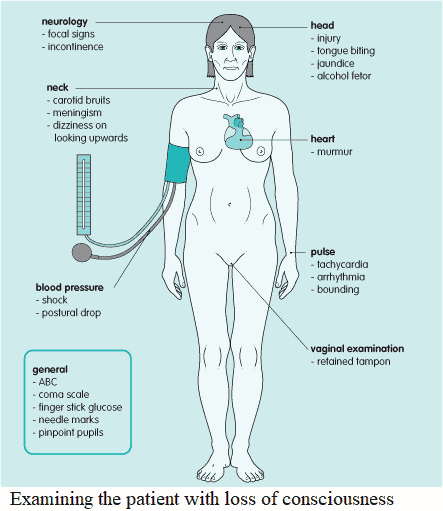

Examining the Patient with Loss of Consciousness

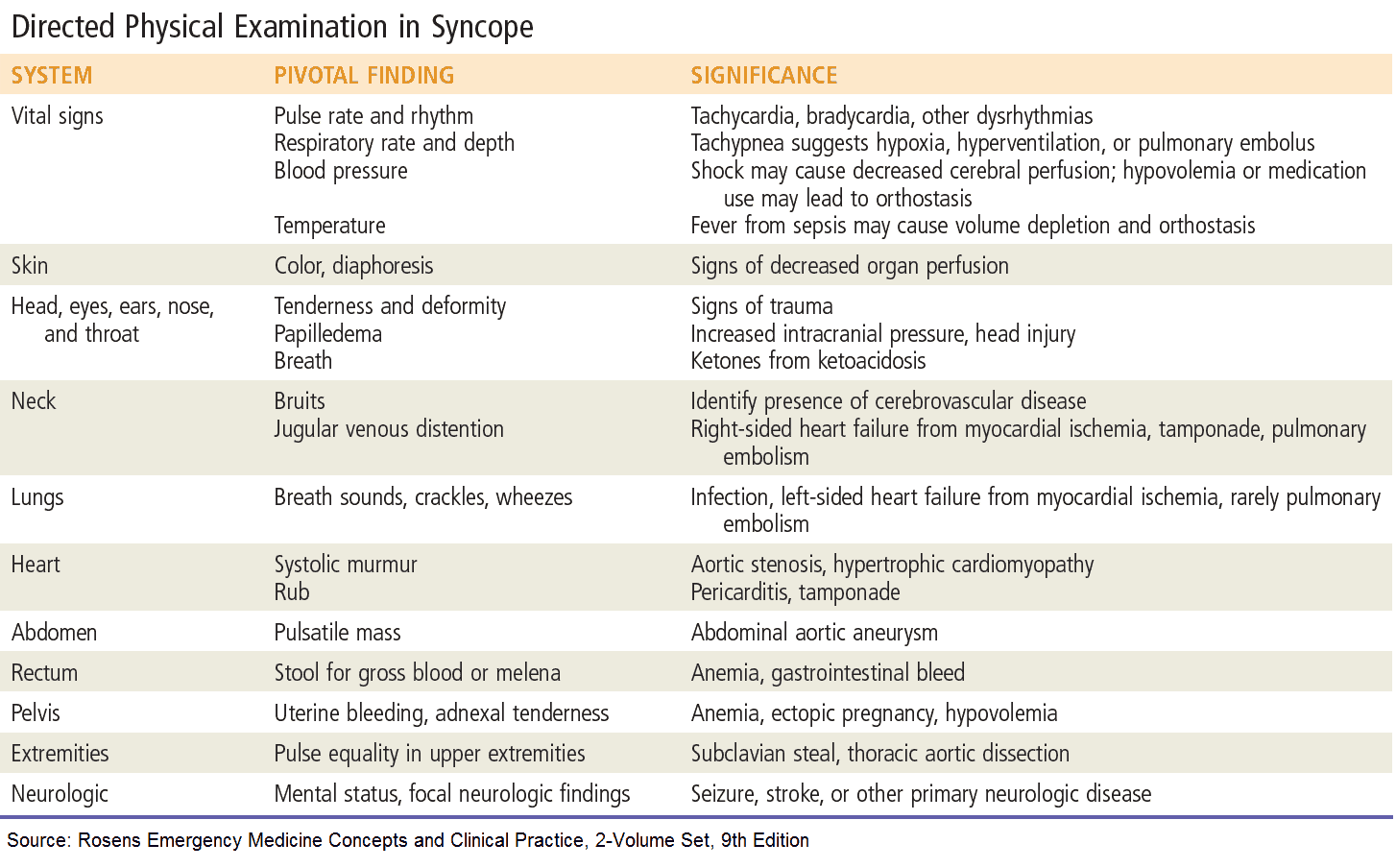

The examination should be in three parts, in the order given below:

- How ill is the patient?

- Is there any evidence of the underlying cause?

- Has the patient been injured as a consequence?

How ill is the patient?

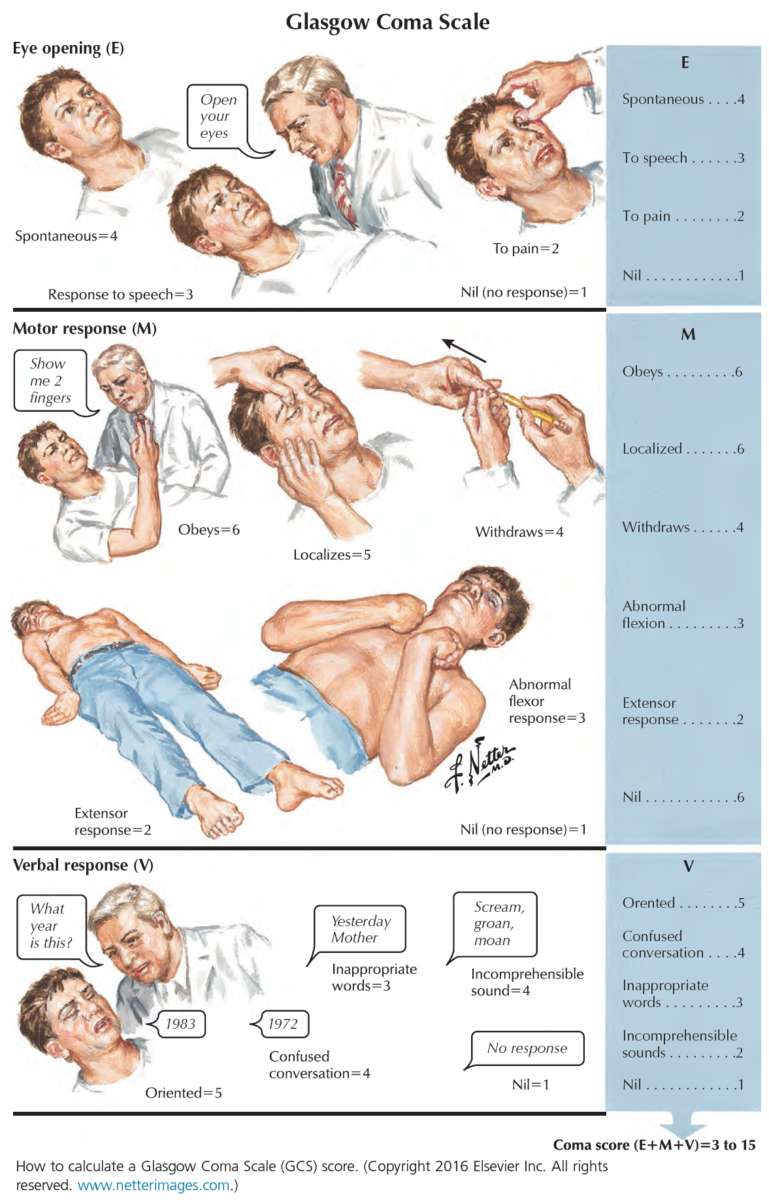

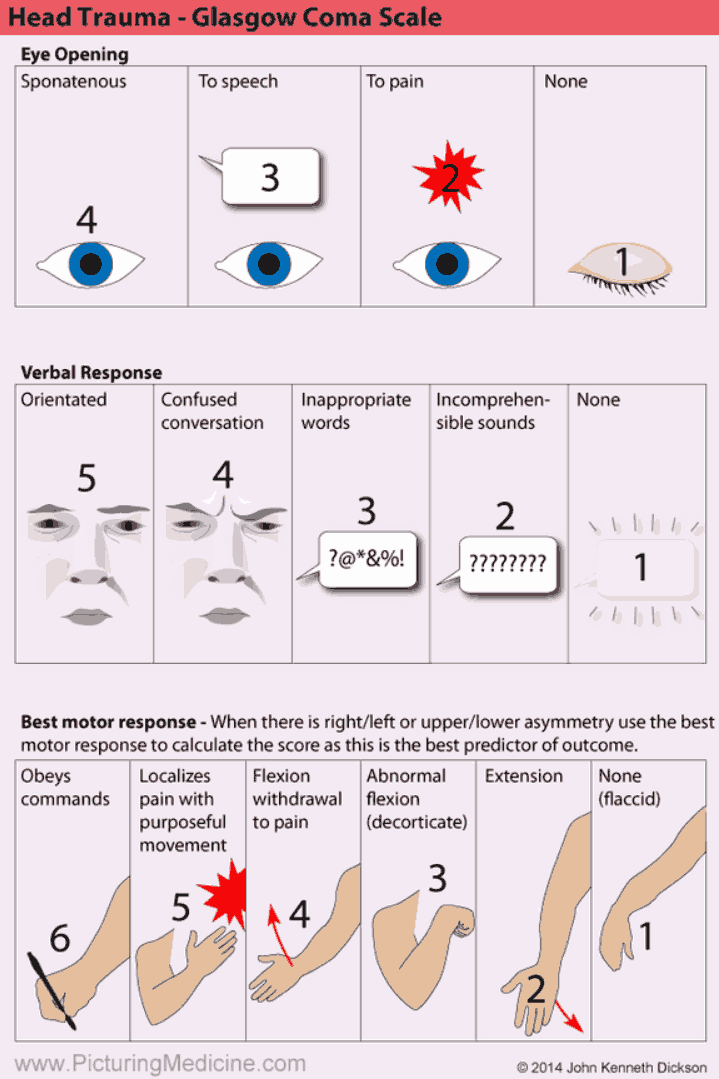

In an unconscious patient, the first priority is to establish that there is a patent airway and effective breathing and circulation (ABC). A rapid assessment of the Glasgow coma scale should then be made as shown in the images below.

Is the patient shocked? Check the blood pressure and pulse.

Are there any clues as to the underlying cause?

The following signs may indicate the underlying cause:

- Tongue injury or incontinence (urinary or fecal): epilepsy.

- Drop in blood pressure on standing: postural hypotension.

- Dizziness on looking upward: vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

- Rapid or irregular pulse or murmur: cardiac cause.

- Evidence of head injury: skull fracture, hematoma, blood or cerebrospinal fluid in ears.

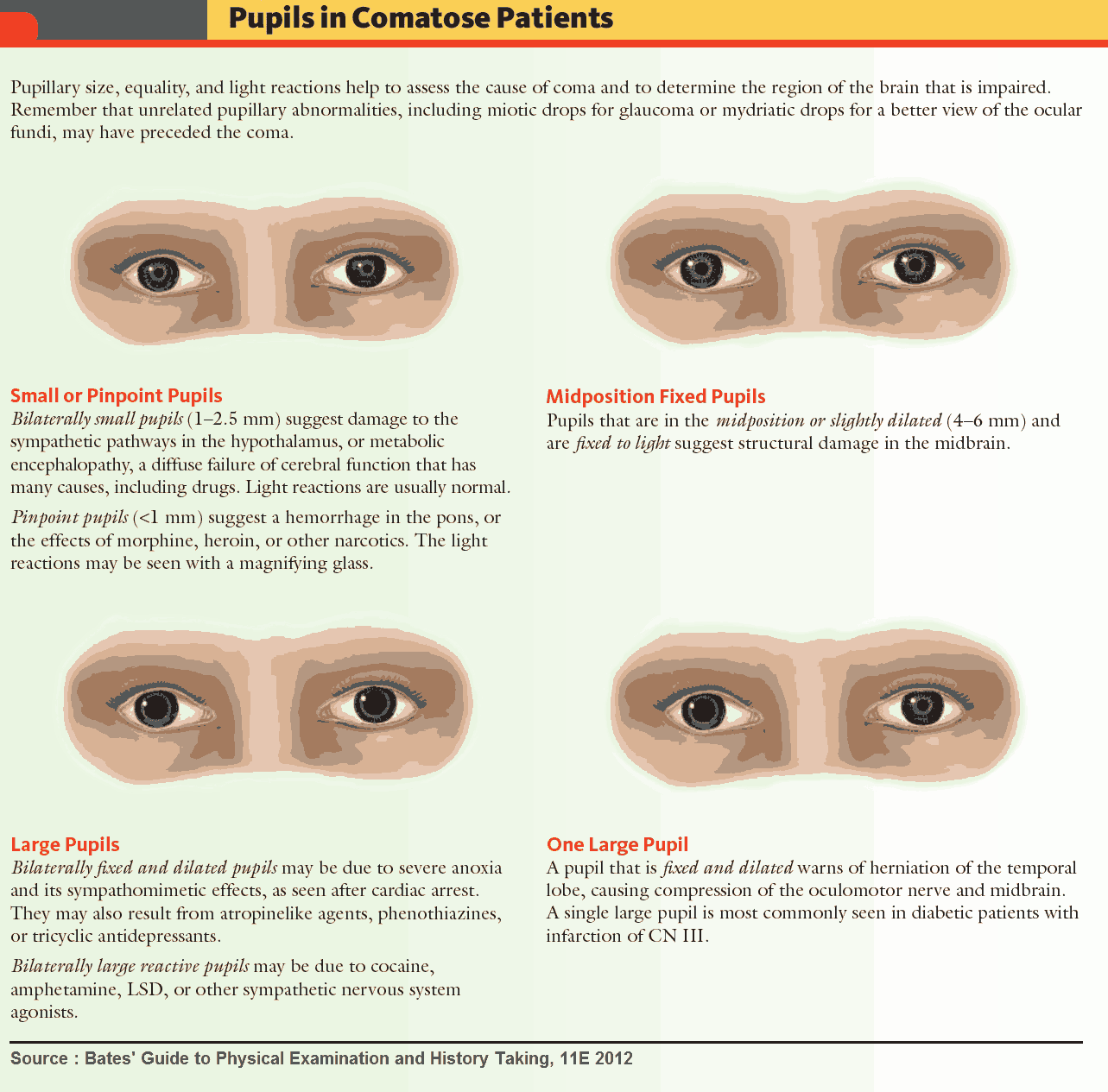

- Needle marks or pinpoint pupils: narcotic overdose.

- Smell of alcohol.

- Meningism: meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage.

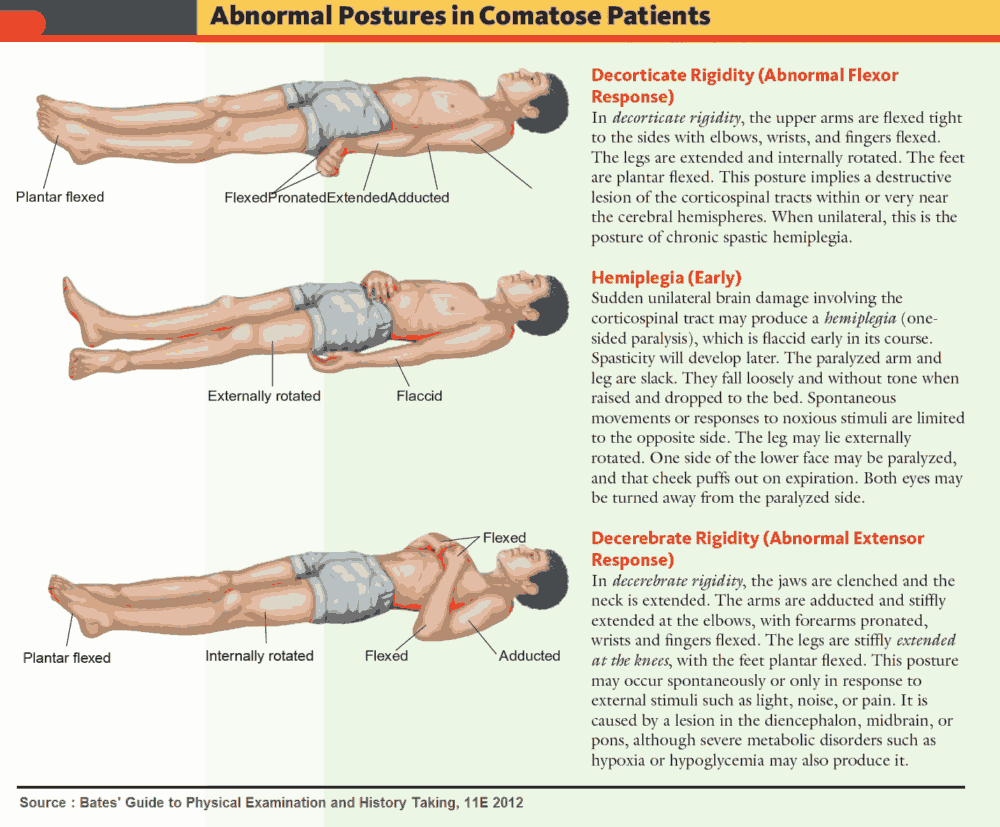

- Focal neurology: intracranial cause such as hemorrhage or infarction.

- Jaundice: hepatic encephalopathy.

- Trousseau’s and Chvostek’s signs: hypocalcemia.

- Papilledema, bounding pulse, asterixis and warm peripheries: hypercapnia.

- Tampons in vagina: toxic shock syndrome.

- Carotid bruits: these are found in atherosclerosis and suggest a possible source of emboli in transient ischemic attacks or stroke.

Has the patient been injured?

If conscious, the patient will be able to describe any injury resulting from the episode. If not, look for bruising or deformities due to fractures. In particular, look for evidence of head injury.

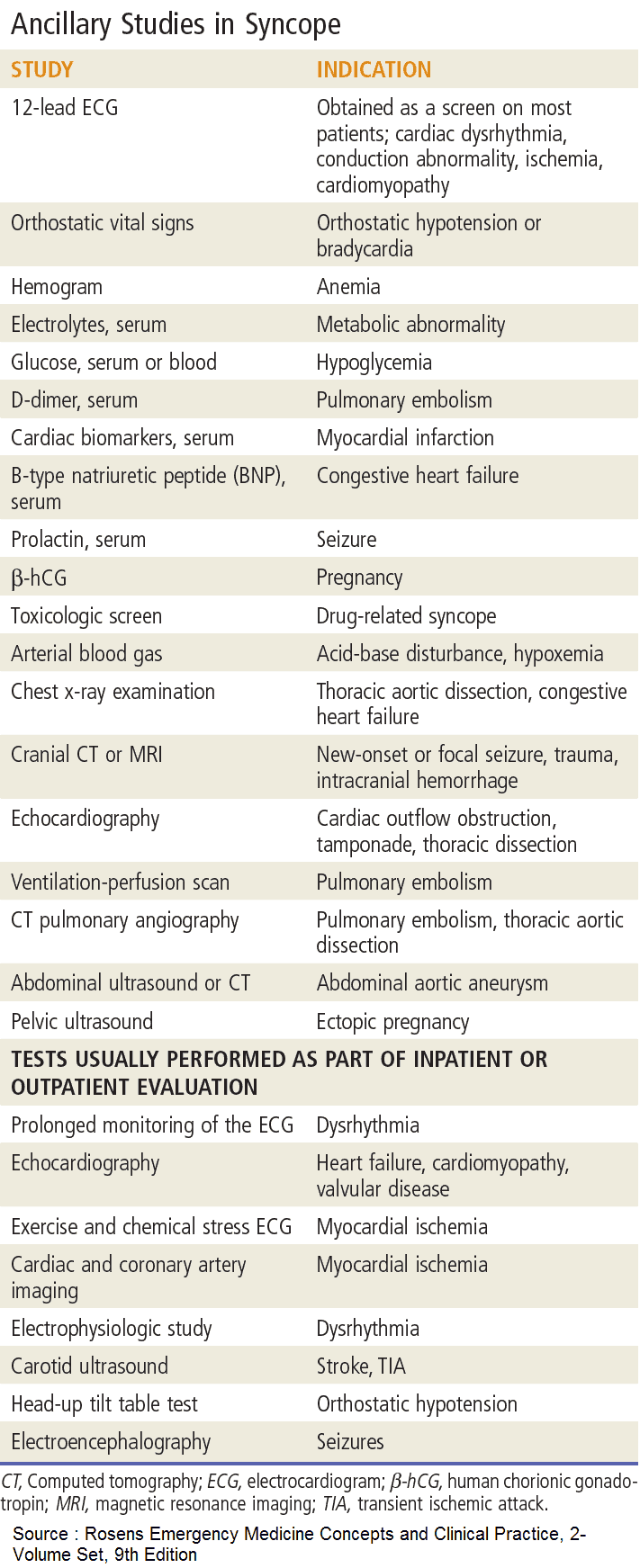

Investigating the Patient with Loss of Consciousness

Investigation will be guided by findings in the history and clinical examination. The following tests are useful in the different clinical scenarios:

- Complete blood count: anemia in severe hemorrhage or hemolysis (malaria); leukocytosis in sepsis.

- Metabolic panel: hypo- or hypernatremia.

- Calcium: hypocalcemia.

- Glucose: hypoglycemia.

- Liver function tests: liver failure.

- Thyroid function tests: hypothyroidism.

- Electrocardiogram: arrhythmia, left ventricular hypertrophy in aortic stenosis and HOCM, prolonged QT interval, bundle-branch block/heart block, sinus bradycardia.

- Arterial blood gases: hypercapnia.

- Chest x-ray: pulmonary disease, aspiration pneumonia.

- Drugs screen: urine and blood.

- Tilt table test: helps to determine vasovagal causes of syncope.

- Electroencephalogram: epilepsy (including subclinical status epilepticus), herpes simplex encephalitis.

- Computed tomography head scan: intracranial pathology.

- Carotid Dopplers: carotid atheroma.

- 24-hour/48-hour ambulatory monitoring or Holter monitor 24-hour tape: arrhythmia.

- ECG/echocardiogram: source of emboli, aortic stenosis, HOCM.

- Lumbar puncture: meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Septic screen, including blood cultures and mid-stream urine.

READ ALSO: Pearls in Syncope ECG Interpretation