Table of Contents

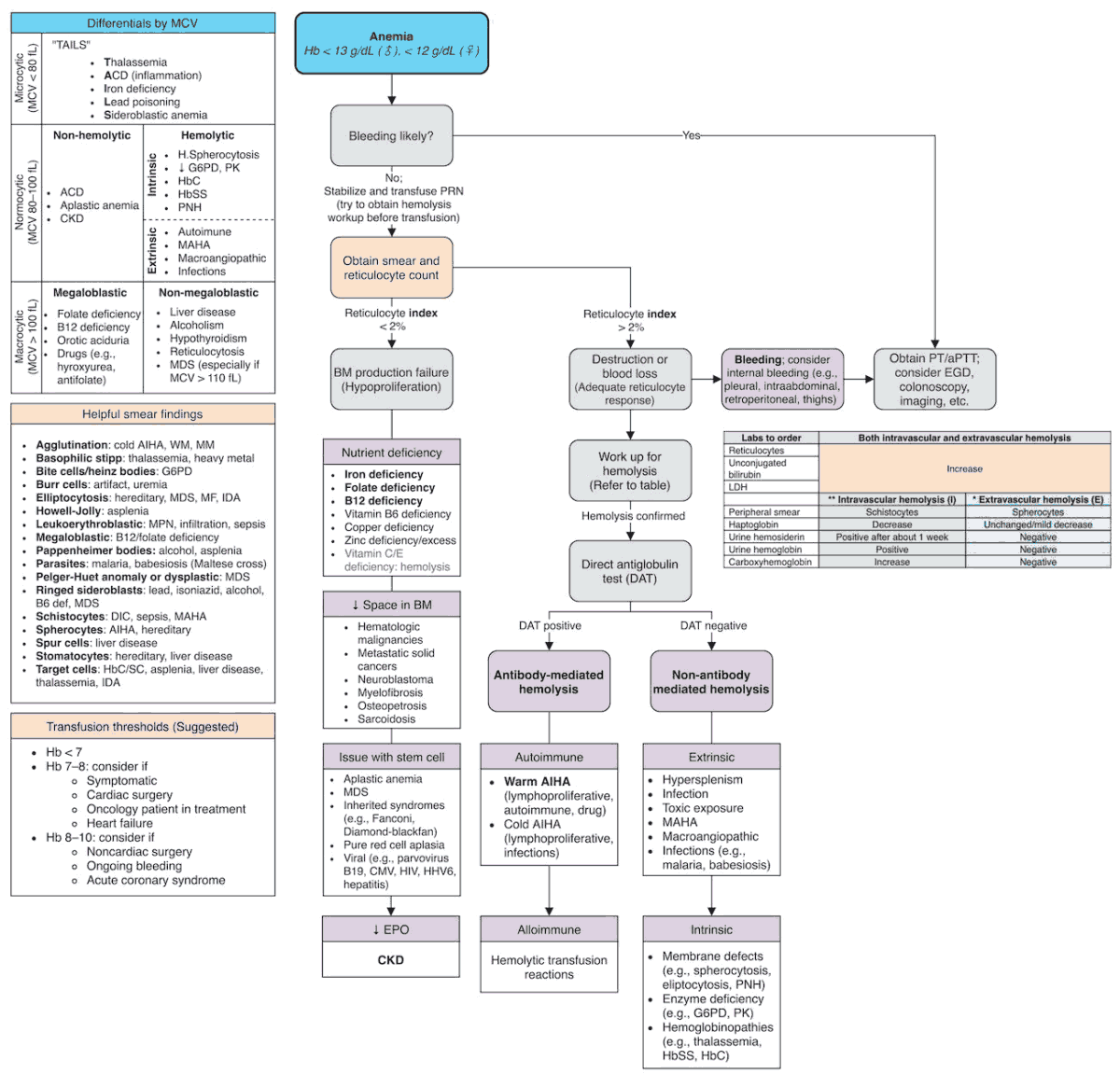

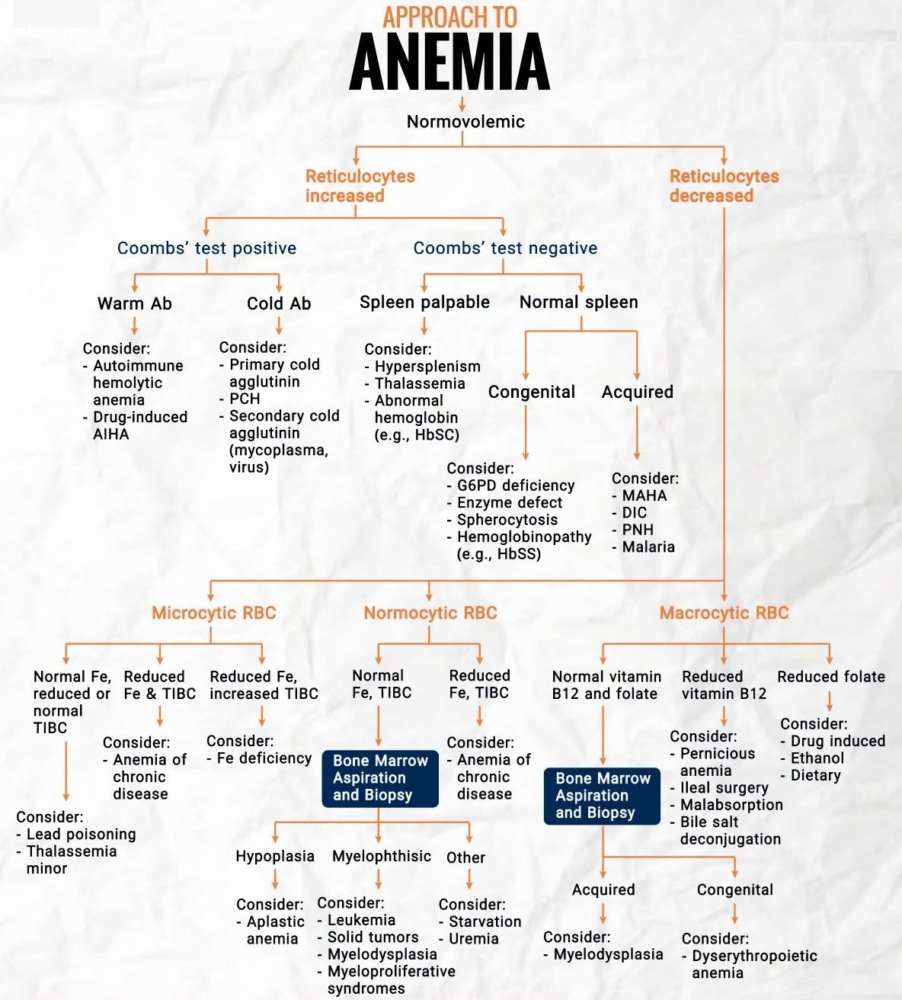

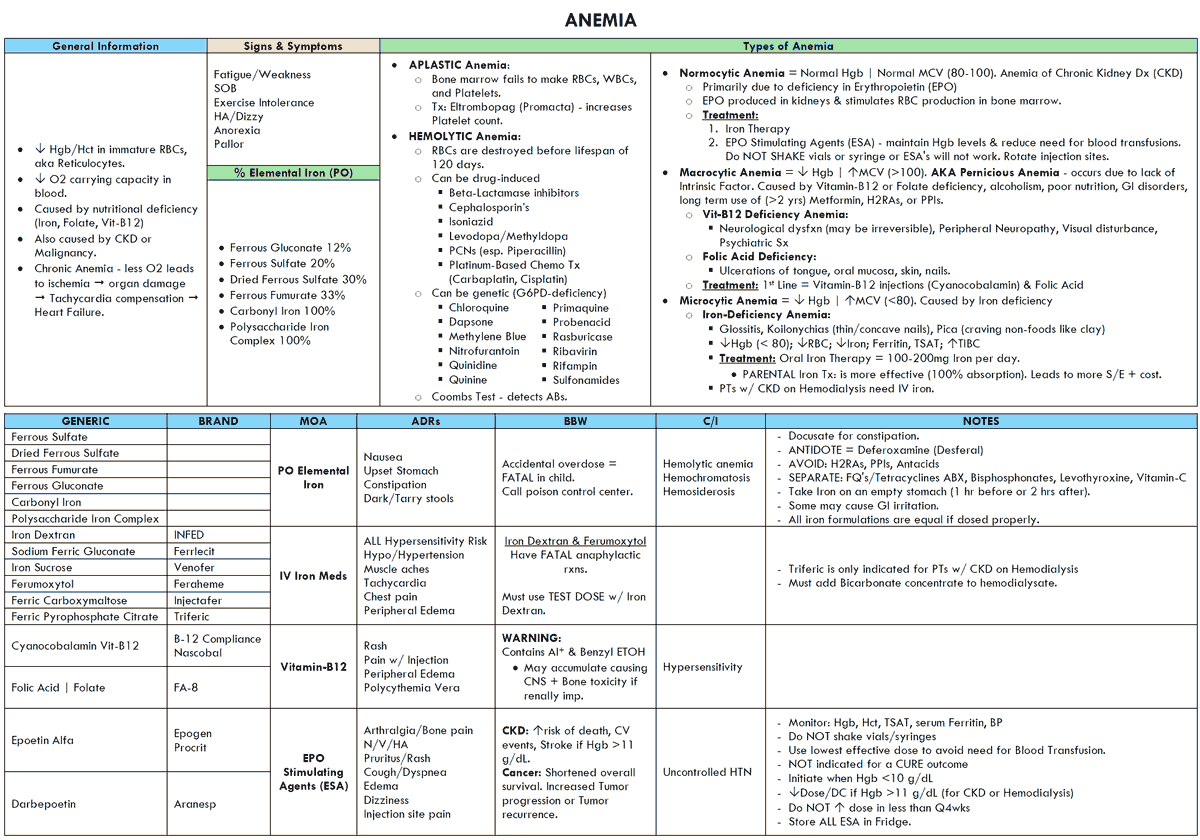

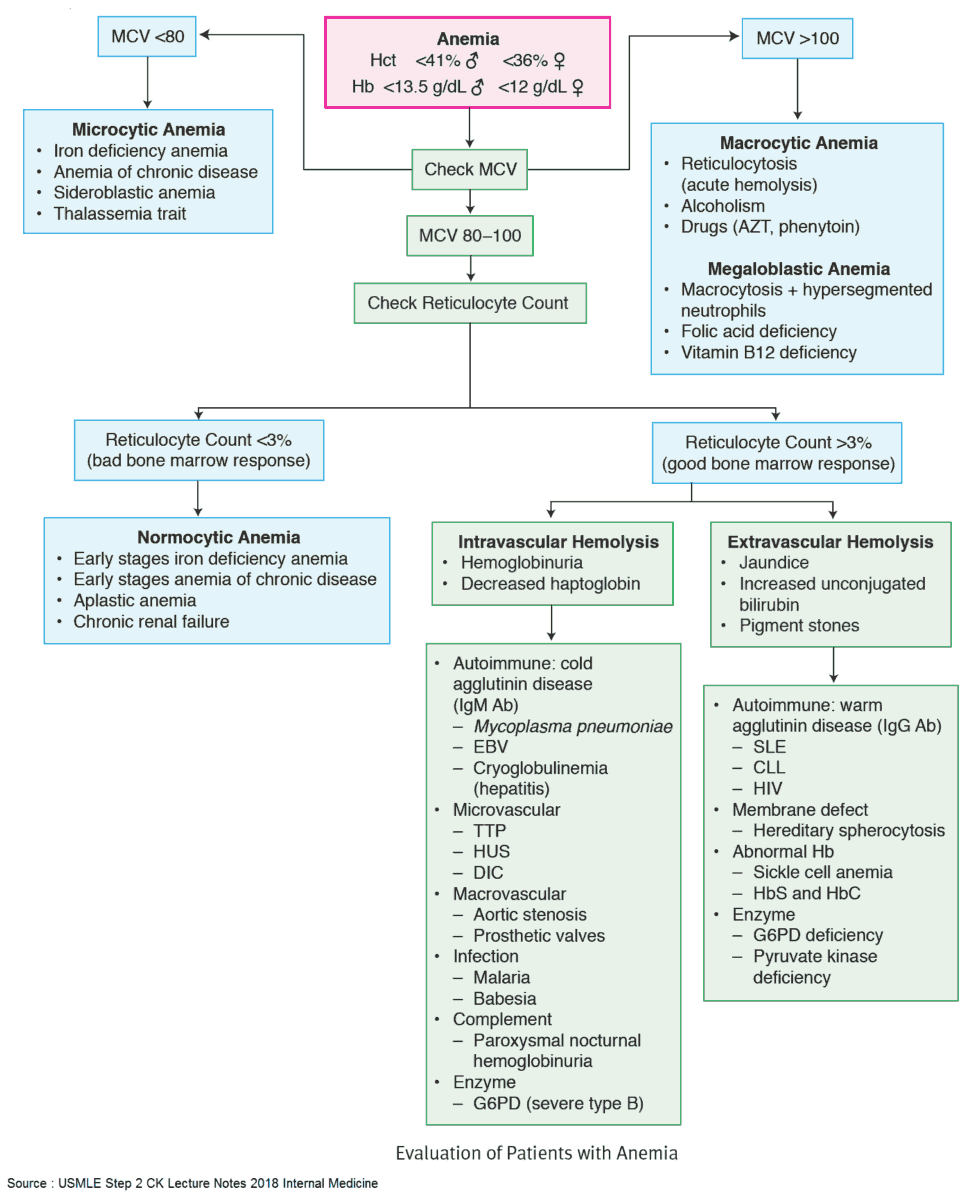

A patient is anemic when the hemoglobin concentration in the blood is less than 13 g/dL (or hematorcit [Hct] less than 39%) in men and 12 g/dL (or Hct less than 36%) in women.

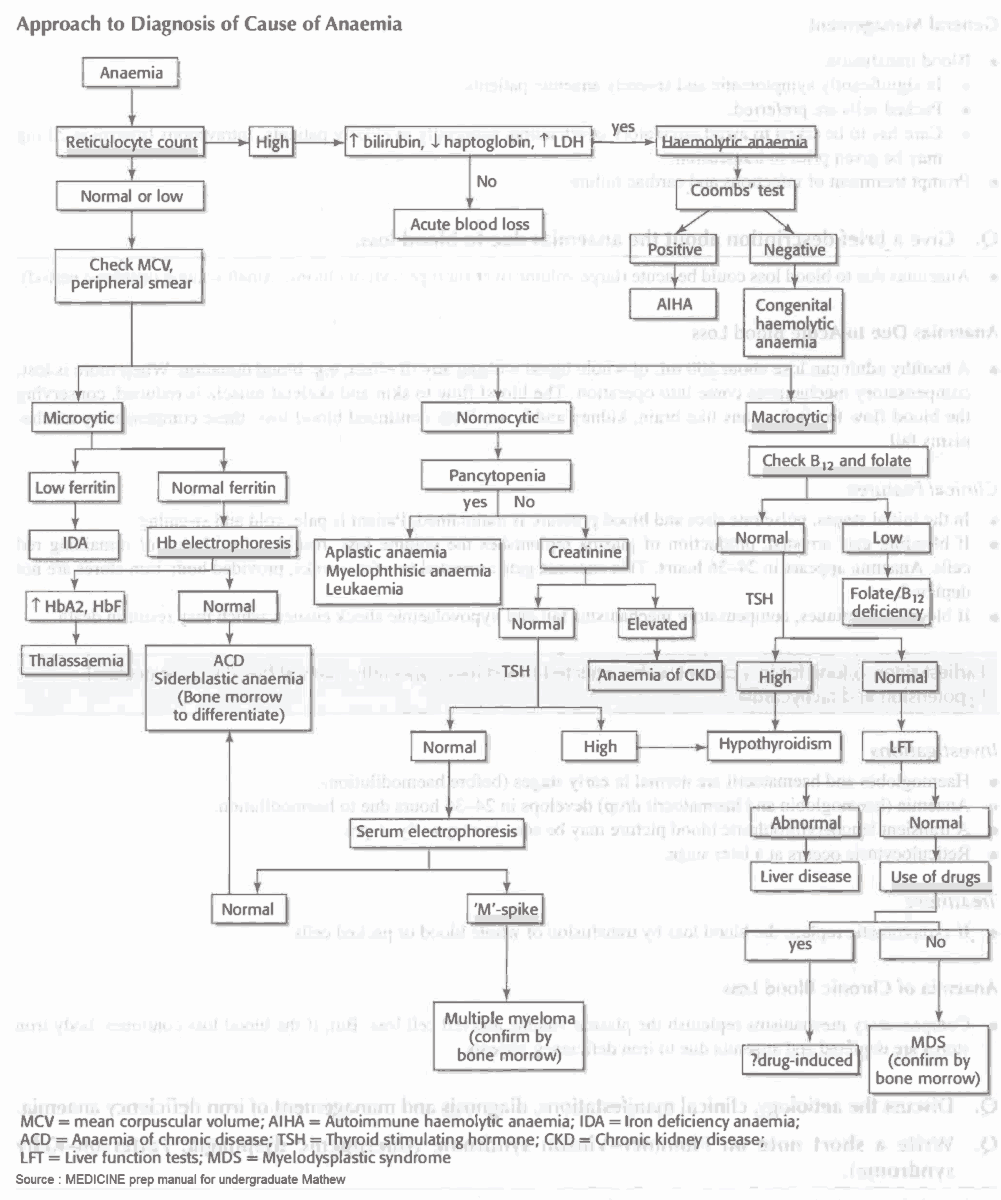

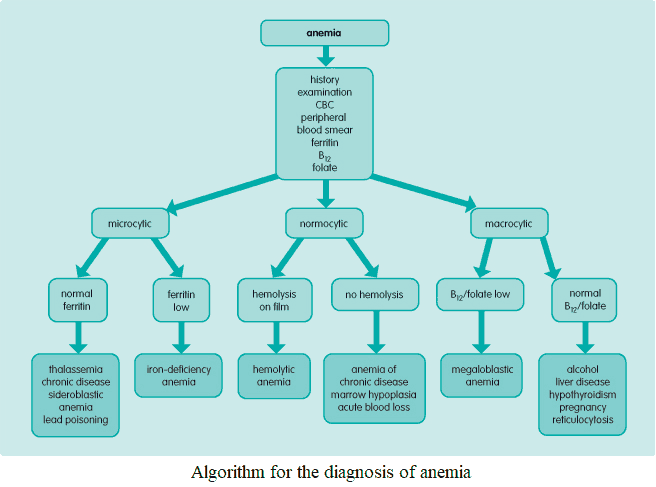

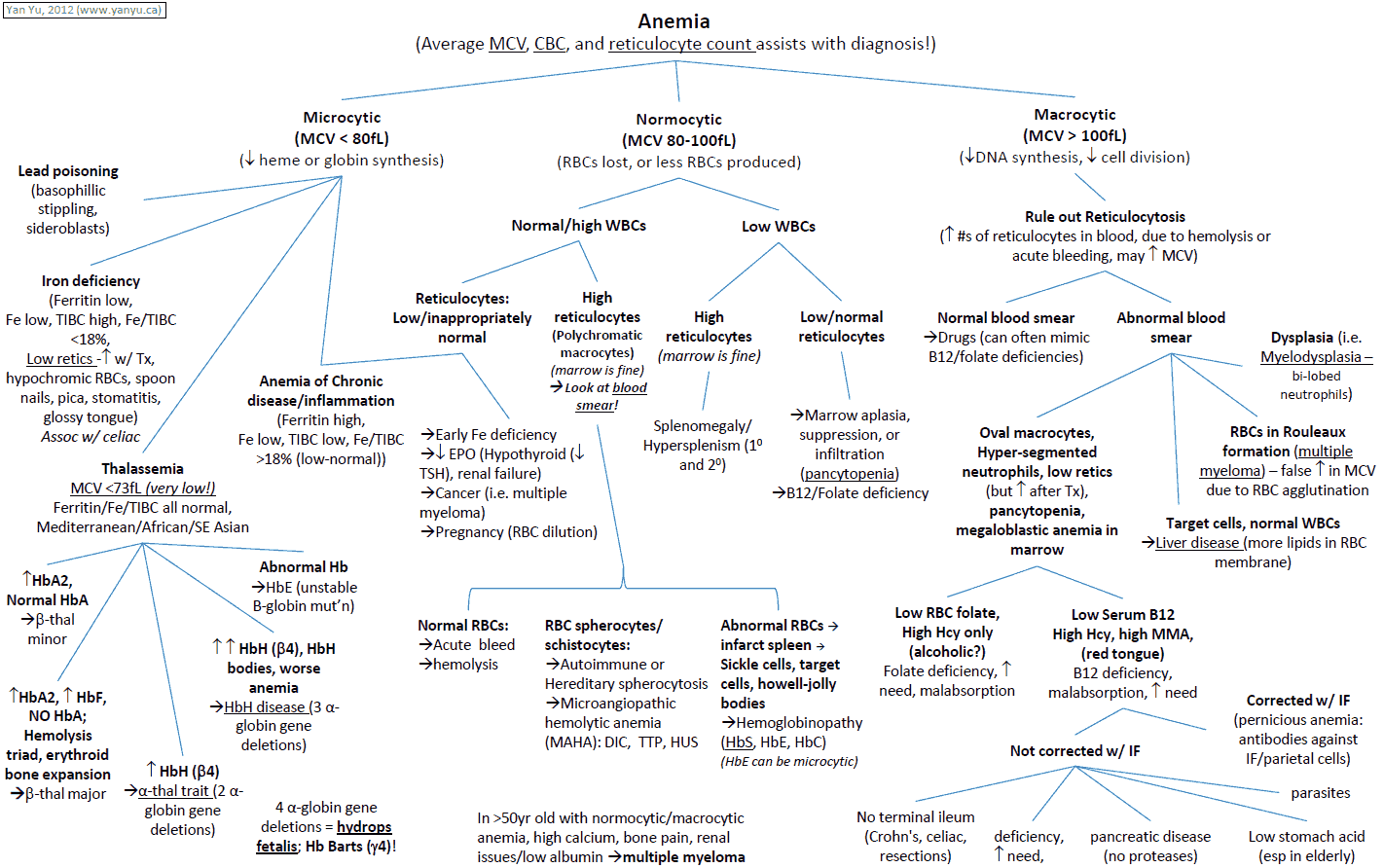

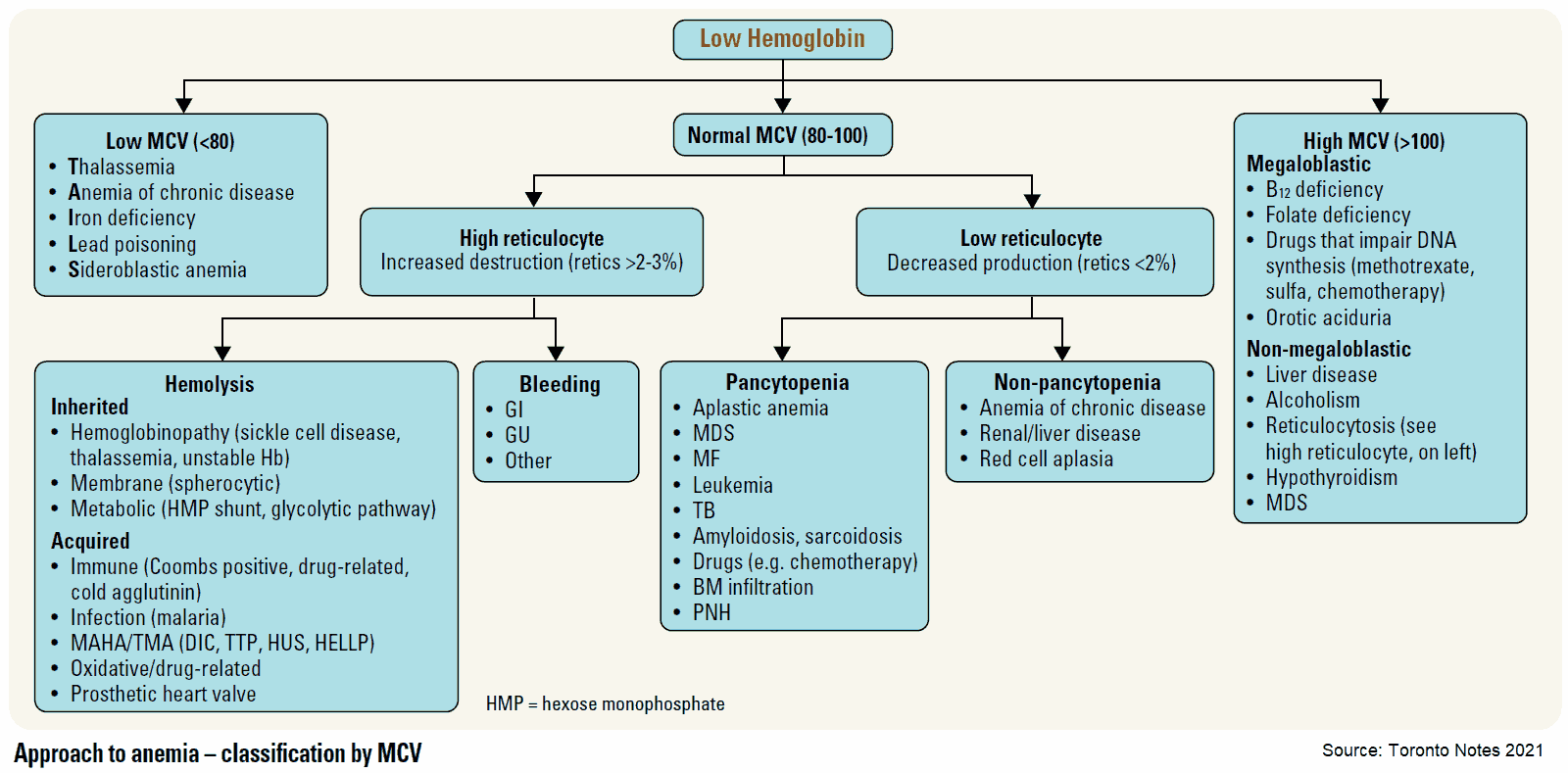

Causes and Differential Diagnosis of Anemia

The size of the red blood cells gives important clues as to the likely underlying abnormality.

Causes of Microcytic red blood cells (Microcytic Anemia)

Microcytic RBCs have a mean cell volume of less than 80 fL; where fL stands for femtoliter (= 10-15 L). Causes include:

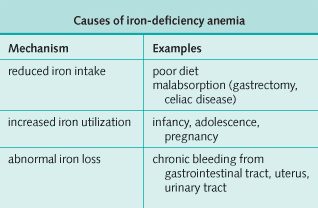

- Iron-deficiency anemia

- Thalassemia

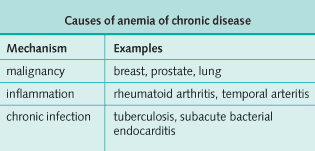

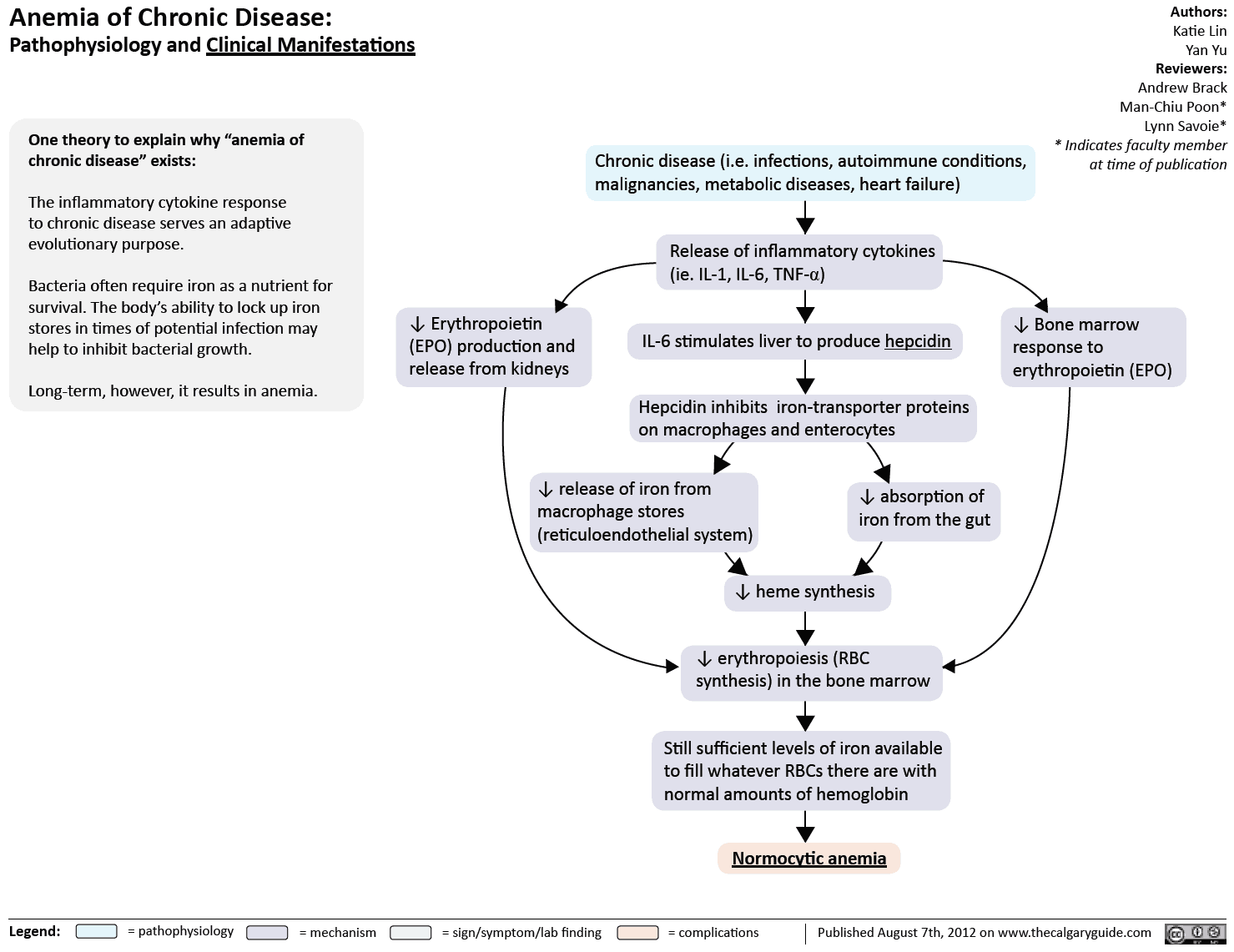

- Anemia of chronic disease

- Sideroblastic anemia

- Lead poisoning

Causes of Normocytic red blood cells (Normocytic Anemia)

Normocytic RBCs have a mean cell volume of 80-95 fL. Causes include:

- Anemia of chronic disease

- Early stages of Iron-deficiency anemia

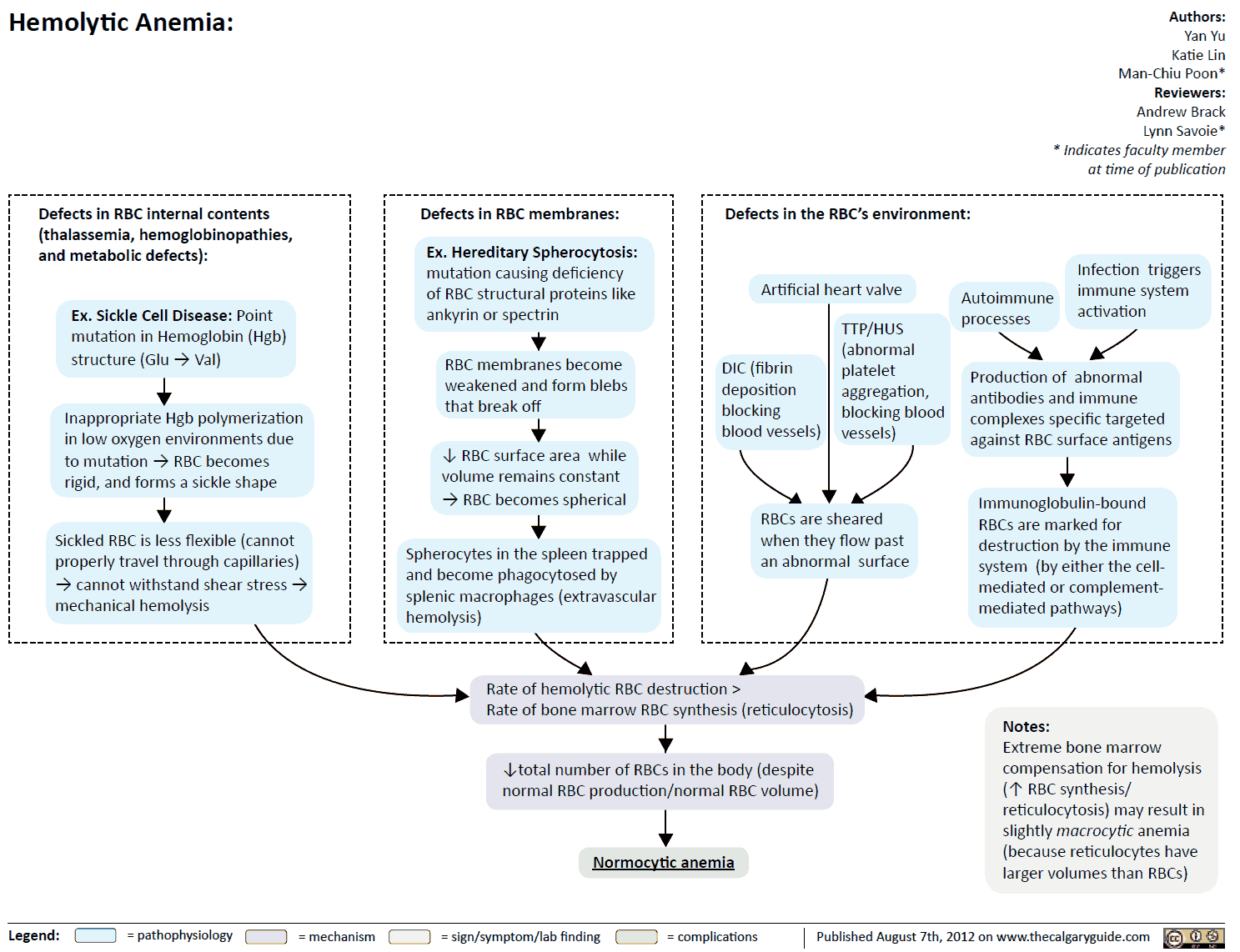

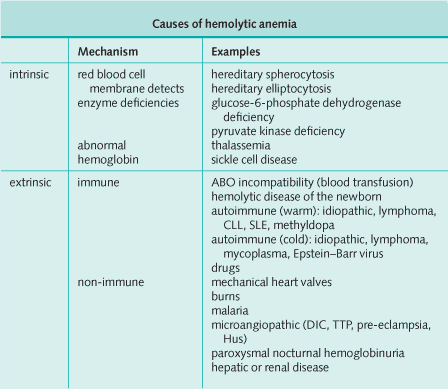

- Hemolysis

- Acute blood loss

- Bone marrow hypoplasia/aplasia (aplastic anemia)

Causes of Macrocytic red blood cells (Macrocytic Anemia)

Macrocytic RBCs have a mean cell volume of more than 95 fL. Causes include:

- Megaloblastic anemia:

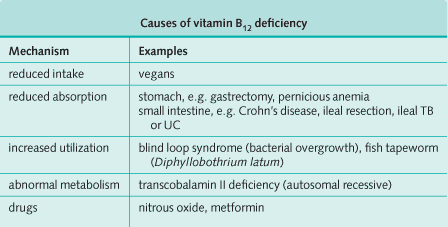

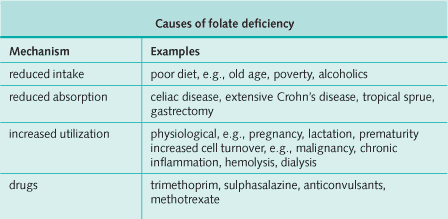

- folate deficiency

- vitamin B12 deficiency

- Normoblastic anemia: alcohol, liver disease, hypothyroidism, pregnancy, reticulocytosis.

- Several drugs can lead to macrocytosis such as azathioprine, methotrexate, zidovudine, hydroxyurea. In fact, in the case of zidovudine macrocytosis is used as a sign that patients are taking the medication.

- Myelodysplastic syndrome.

Symptoms and History in the Anemic Patient

It is important to establish first how symptomatic the anemia is. The history should then focus on whether any complications of anemia are present and whether there are any clues as to the likely underlying diagnosis.

Symptoms of Anemia

When anemia develops over a long time, the hemoglobin can be very low before symptoms occur. Anemia is tolerated less well in the elderly. The following symptoms may present:

- Asymptomatic: particularly if the anemia develops over a long time

- Lethargy

- Shortness of breath: most marked on exertion

- Lightheadedness

- Syncope

- Palpitations

- Headaches

Symptoms of Complications

- Symptoms of cardiac failure

- Angina

- Ischemic claudication

- Visual disturbance due to retinal hemorrhage: very rare-the anemia must be severe.

Evidence to Suggest Underlying Cause

- Specific symptoms: menorrhagia, change in bowel habit (including melena or hematochezia), dyspepsia, weight loss, headache.

- Of note, in adult over 50 years old, microcytic anemia is due to a GI bleed until proved otherwise. It is imperative to ask about dark, malodorous stools and other risk factors for GI bleeding as noted above (e.g., NSAID use).

- Pre-existing illness: rheumatoid arthritis, previous abdominal surgery, dialysis.

- Family history: hemolytic anemia.

- Drug history: salicylates (iron deficiency), anticonvulsants (folate deficiency).

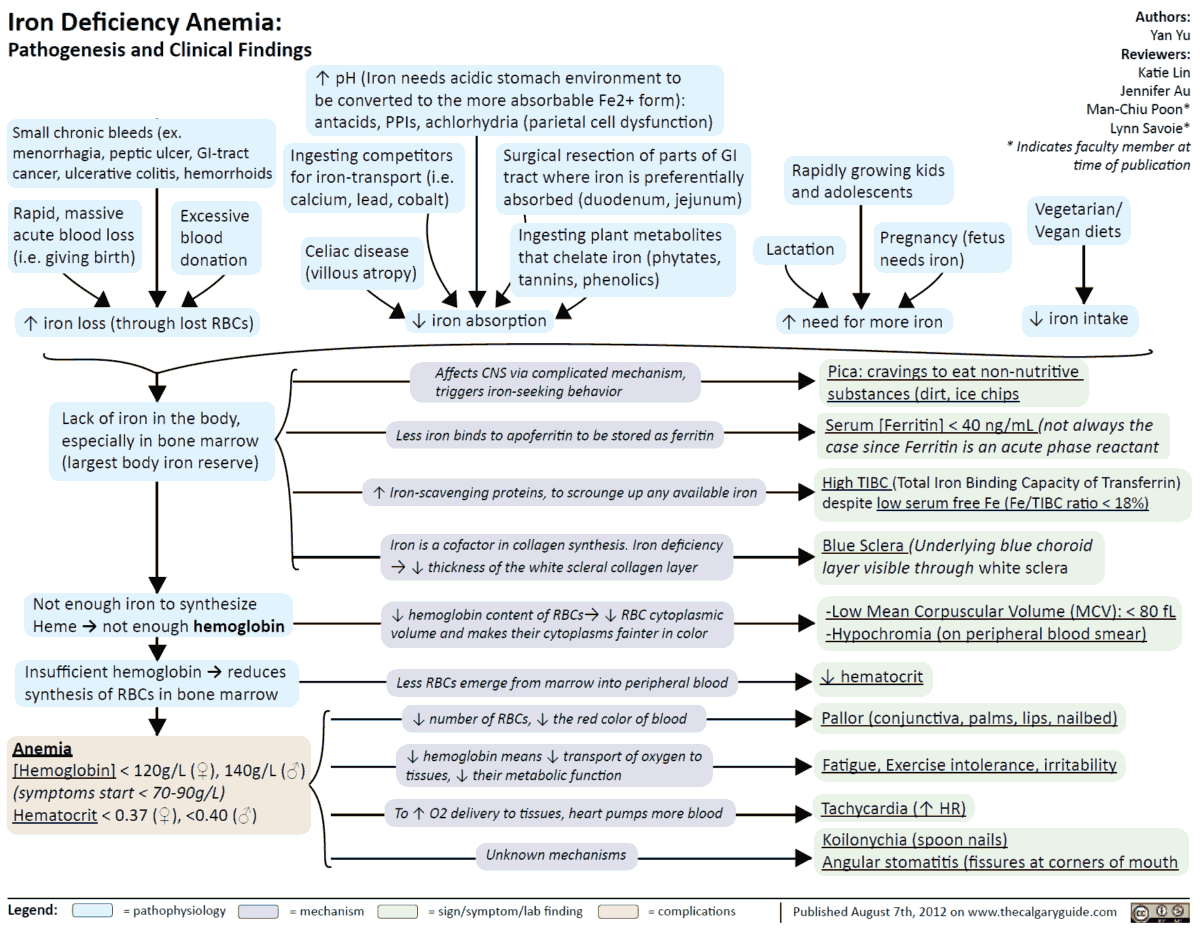

- Diet: vegans (vitamin B12 deficiency), alcoholics (folate deficiency).

- Pica (craving for specific and often bizarre foods): iron deficiency.

- Pregnancy: folate deficiency

- Dysphagia plus iron-deficiency anemia: think of Plummer-Vinson or Paterson-Brown-Kelly syndrome (postcricoid esophageal web).

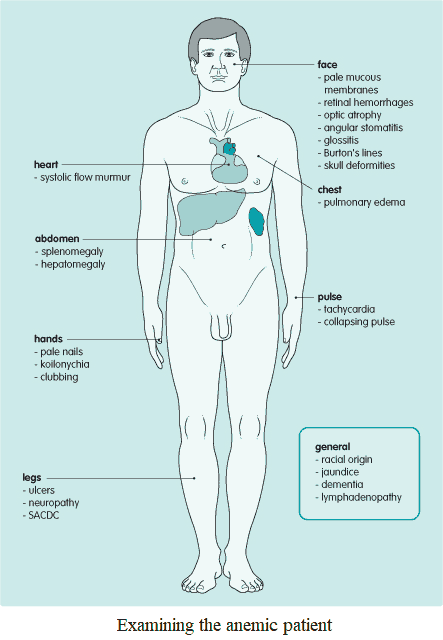

Examination and Signs in the Anemic Patient

Signs of anemia and its consequences

- Pallor: mucous membranes (mouth and conjunctivae), nails, skin creases

- Hyperdynamic circulation: tachycardia, collapsing pulse, systolic flow murmur

- Cardiac failure

- Retinal hemorrhages

Signs of underlying disease

A full general examination should always be performed, including breast examination and rectal examination in iron deficiency. Specific abnormalities include the following:

- Glossitis: megaloblastic anemia, iron deficiency.

- Angular stomatitis, koilonychia: iron deficiency.

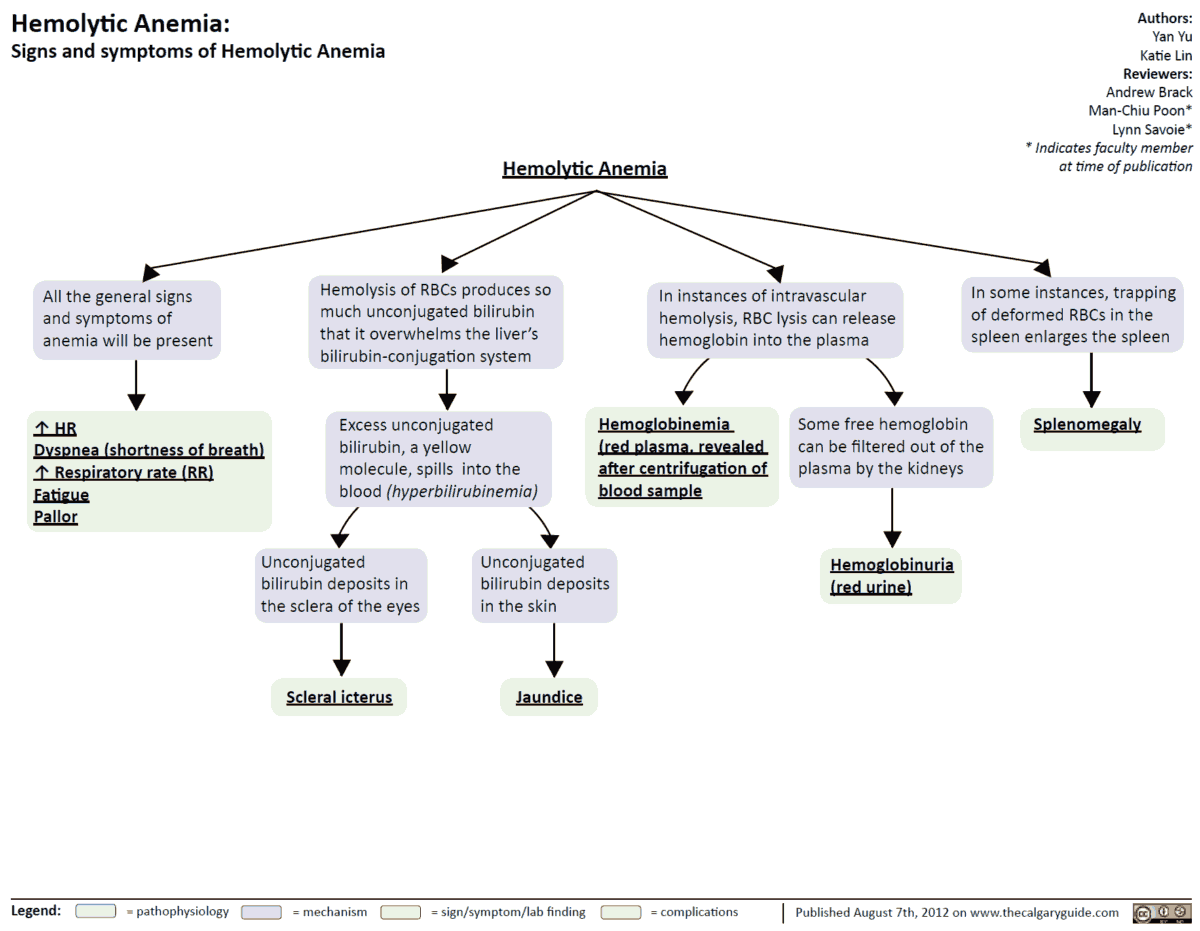

- Jaundice: hemolysis, megaloblastic anemia (mild).

- Splenomegaly: hemolysis, megaloblastic anemia

- Leg ulcers: sickle cell disease.

- Bone deformities: thalassemia.

- Peripheral neuropathy, optic atrophy, subacute combined degeneration of the cord, and dementia are all neurologic sequelae of vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Blue line on the gums (Burton’s line), peripheral motor neuropathy, encephalopathy are seen in lead poisoning.

Note the racial origin of the patient as thalassemia is more common in people from South-East Asia and China, while sickle cell anemia is more common among Africans.

Investigating and Diagnosing the Anemic Patient

General investigations

Complete blood count

- Hemoglobin: anemia

- Mean corpuscular volume: underlying pathologies

- White cell count:

- if low, consider general bone marrow failure

- if high, consider infection, inflammation, or malignancy

- Platelet count:

- if low, consider general bone marrow failure

- if high, consider infection, inflammation, or malignancy

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate will be raised in infection, inflammation, or malignancy.

Reticulocyte count

Reticulocytes are young erythrocytes that normally constitute only 0.5-2.0% of circulating RBCs. The reticulocyte count is increased if RBC production is increased and red cells are prematurely released into the circulation.

This occurs following hemorrhage, in chronic hemolysis, or with vitamin B12, folate, or iron replacement, when there has been a deficiency. This means that macrocytic anemia is normal in some cases (as the body replenishes its circulating RBC volume).

Be aware that if the patient does not have macrocytosis after hemorrhage, etc., this may be a sign of inadequate RBC production.

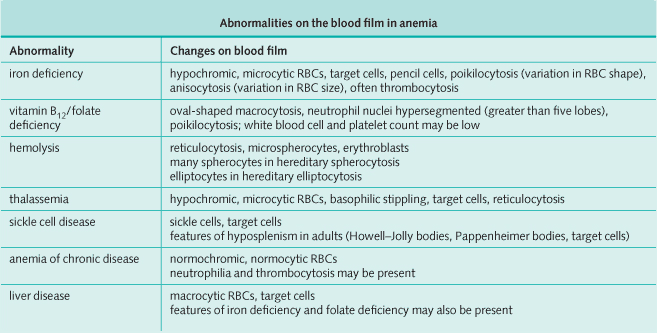

Peripheral blood smear

The peripheral blood smear can provide diagnostic information.

Bone marrow

- Not necessary when the diagnosis is obvious (e.g., iron deficiency).

- Bone marrow aspirate gives information regarding the development of different cell lines, the proportion of these different cell lines, infiltration by abnormal cells (e.g., infiltration with metastatic carcinoma), and the presence of iron stores.

- Bone marrow trephine (core biopsy) provides structural information regarding bone marrow architecture and infiltration.

Specific investigations

All patients with anemia should have measurement of serum ferritin, vitamin B12, and RBC folate, as more than one deficiency can occur at the same time.

Investigations for Iron deficiency

- Serum ferritin: low in iron deficiency but raised in iron overload, hemochromatosis and anemia of chronic disease (occasionally).

- Serum iron: low.

- Total iron-binding capacity: increased.

- Menorrhagia or pregnancy: no further investigations are necessary.

- If no menorrhagia or pregnancy: consider upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, rectal examination, and sigmoidoscopy with colonoscopy or barium enema.

- No obvious cause: consider mesenteric angiogram for angiodysplasia.

Investigations for Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Serum vitamin B12: low.

- Bilirubin: mildly raised-intramedullary destruction of abnormal RBCs.

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): elevated-intramedullary destruction of abnormal RBCs.

- Gastric parietal antibodies: positive in 90% of patients with pernicious anemia.

- Intrinsic factor antibodies: positive in approximately 50% of patients with pernicious anemia.

- Schilling test: the patient is given a loading dose of 1000 mg vitamin B12 intramuscularly, followed by a small oral dose of radioactive vitamin B12, and excretion is then measured in the urine; vitamin B12 malabsorption is corrected by giving intrinsic factor with labeled vitamin in pernicious anemia, but persists despite the use of intrinsic factor in intestinal disease.

- Endoscopy or barium meal and follow through: may be necessary in underlying intestinal disease.

Investigations for Folate deficiency

- RBC folate: more reliable than serum folate.

- Bilirubin: mildly raised-intramedullary destruction of abnormal RBCs.

- LDH: elevated-intramedullary destruction of abnormal RBCs.

- Tests for intestinal malabsorption: including jejunal biopsy, may be necessary when the diagnosis is not clear.

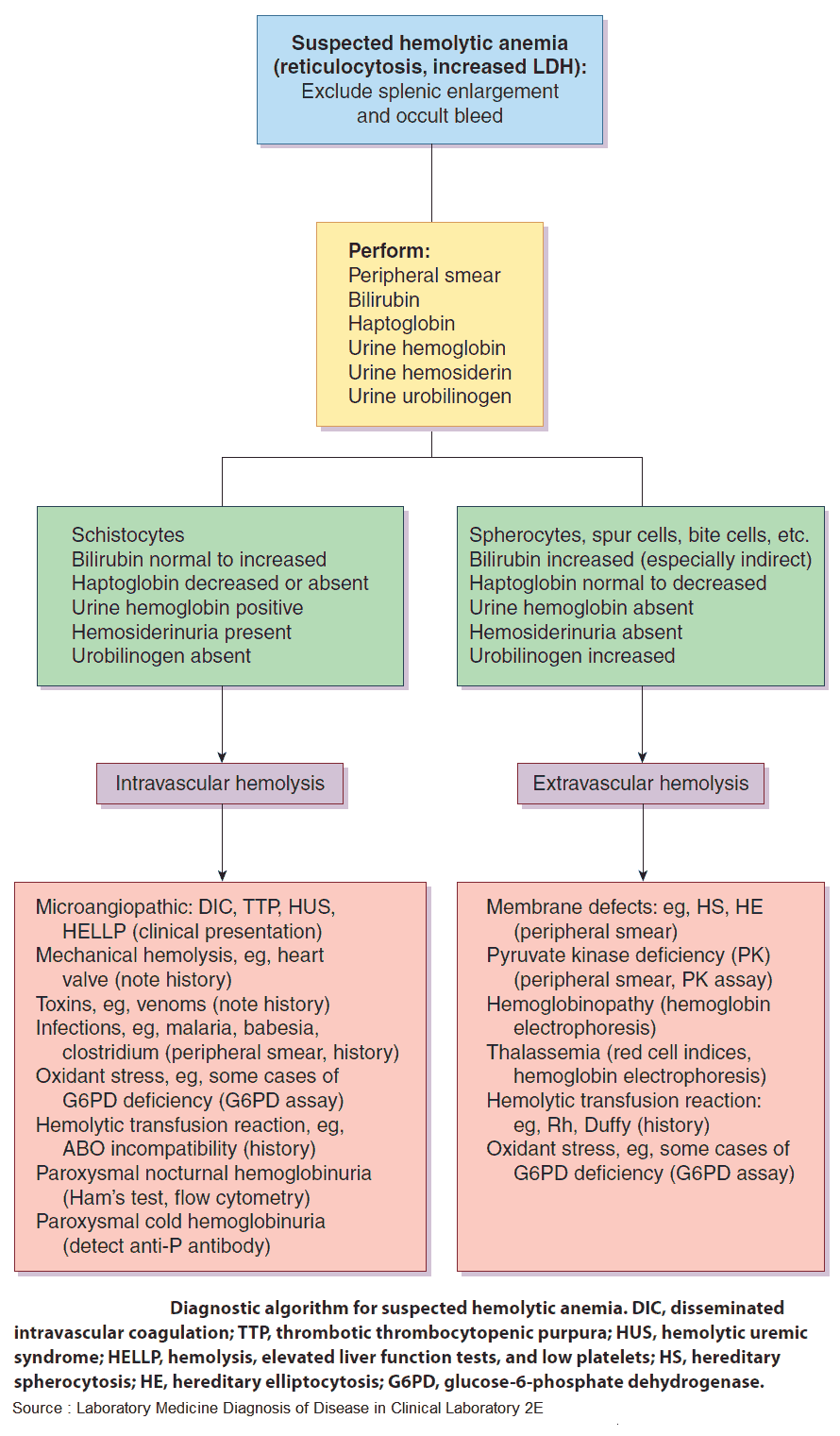

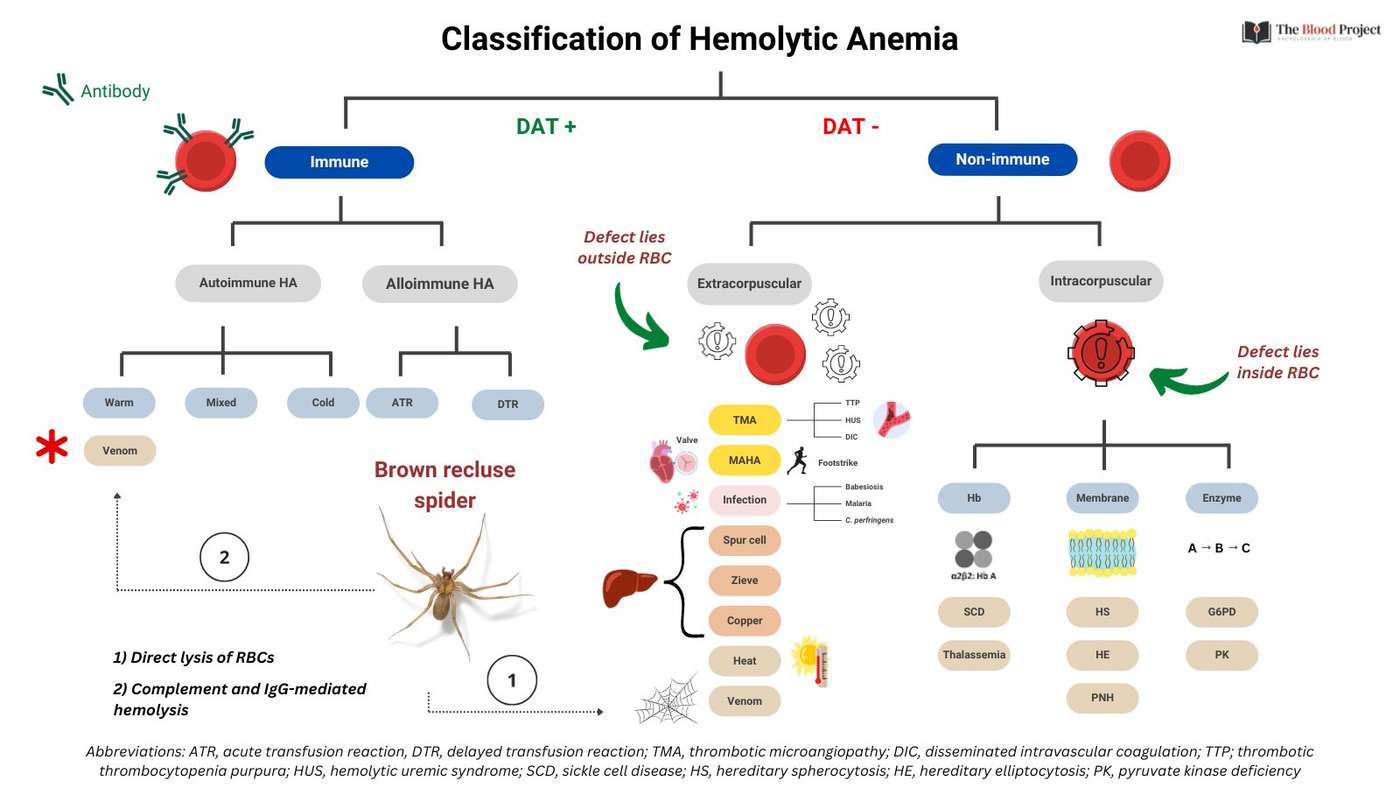

Investigations for Hemolysis

- Serum bilirubin: raised and unconjugated.

- Serum haptoglobins: reduced or absent.

- Fecal stercobilinogen: raised.

- Urinary urobilinogen: raised.

- Reticulocyte count: raised.

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis: abnormal in thalassemia and sickle cell disease.

- Coombs’ test: positive in autoimmune hemolytic anemias.

- Osmotic fragility: increased if spherocytes are present.

- Enzyme assays: available in specialist centers only for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate kinase deficiencies.

- Ham’s test: positive in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

Investigations for Anemia of chronic disease

- Ferritin: high (ferritin is an acute-phase protein).

- Serum iron: low.

- Total iron-binding capacity: low.

- Serum vitamin B12: normal.

- RBC folate: normal.

- Other investigations should be directed by the clinical scenario. Consider:

- erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- C-reactive protein

- autoantibody screen

- sepsis screen

- search for occult malignancy

![Read more about the article All About Leukemia: From Diagnosis to Treatment [A Comprehensive Overview]](https://manualofmedicine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Classification-of-Leukemias-According-to-Cell-Type-and-Lineage-300x213.png)