Table of Contents

Shortness of breath (dyspnea) is the subjective sensation of breathlessness which is excessive for any given level of activity.

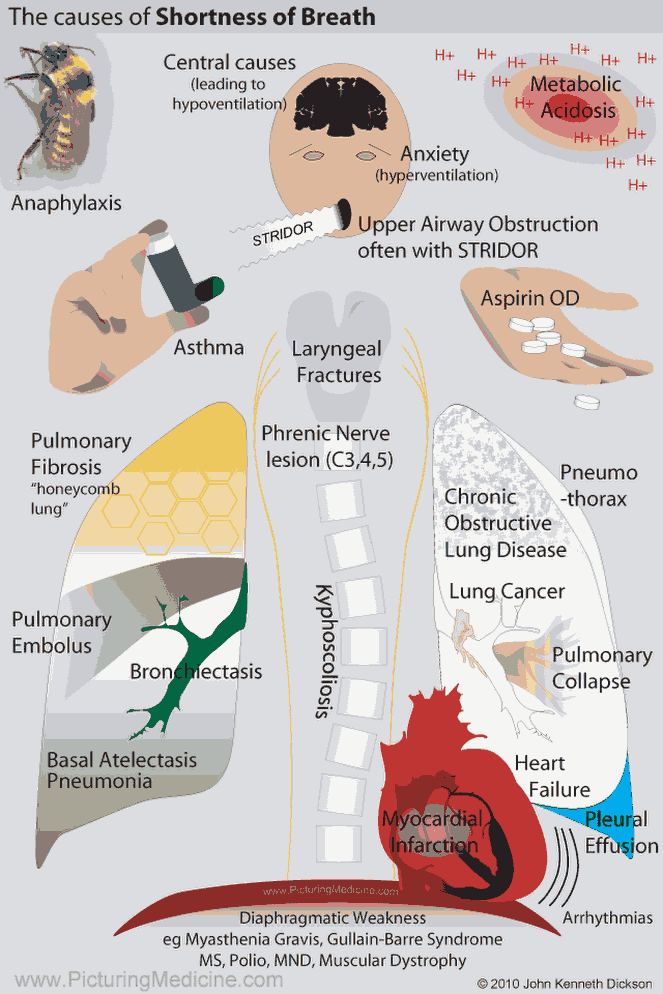

It is important to remember that any component of the respiratory system can cause dyspnea. Therefore, in making a differential diagnosis for dyspnea, think from the respiratory drive of the brain all the way to the individual alveoli.

For example, remember that the peripheral nerves, respiratory muscles, lung parenchyma, airways, heart, and red blood cell (RBC) count are separate entities, each of which can cause shortness of breath.

Causes of Shortness of Breath (Dyspnea)

- Pulmonary disease: disorders of the airways, lung parenchyma, pleura, respiratory muscles, or chest wall (pulmonary embolus, COPD, pneumonia, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, neoplasm, aspiration, ARDS, asthma, interstitial lung disease, any chest wall disease or neurologic disorder that affects respiratory drive).

- Cardiac disease: when it is the result of left ventricular failure (LVF) from any cause, such as coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease (aortic stenosis/regurgitation, mitral stenosis/regurgitation, pulmonary stenosis), or arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia).

- Metabolic disease (e.g., thyrotoxicosis, ketoacidosis, sepsis, drug overdose).

- Anemia.

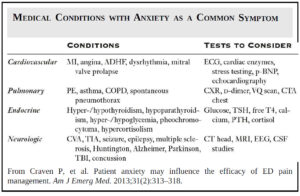

- Psychogenic causes (e.g., anxiety or hyperventilation [psychogenic dyspnea]).

History in the Patient with Shortness of Breath (Dyspnea)

How breathless is the patient (severity)? Try to quantify exercise tolerance (e.g., distance walked on the flat or on hills, while dressing, climbing stairs).

Orthopnea is breathlessness on lying down. It is characteristic of heart failure but can occur with airways obstruction or, more rarely, with bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. Ask patients where they slept last night; if the answer is in a chair, the patient has severe orthopnea. Also ask about how many pillows the patient uses at night.

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea is breathlessness that wakes the patient from sleep and is generally a symptom of cardiac disease.

Determining the patient’s exercise tolerance gives a useful marker of the progression of symptoms.

The onset of breathlessness will often give a clue to its etiology:

- Acute onset may be due to a foreign body, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, asthma, or acute pulmonary edema.

- Subacute onset is more suggestive of parenchymal disease (e.g., alveolitis; pleural effusion; pneumonia; carcinoma of the bronchus or trachea).

- Chronic onset is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis, occupational fibrotic lung disease, nonrespiratory causes (e.g., LVF, anemia, or hyperthyroidism).

In addition to the above, the following factors should be assessed when taking a history from a patient with breathlessness:

- Is the breathlessness associated with a cough? A chronic persistent cough may be due to smoking, asthma, COPD, drugs (especially angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors), occupational agents, cardiac failure, or psychogenic factors.

- How long has the cough been present?

- Is the cough worse at any particular time of day?

- Are there any precipitating factors?

- If there is sputum, ask what it looks like.

- Does the patient have hemoptysis? This is coughing up blood-either frank blood or blood-tinged sputum. It needs to be distinguished from hematemesis and nasopharyngeal bleeding.

- Ask about stridor (a harsh sound caused by turbulent airflow through a narrowed airway). Inspiratory stridor suggests extrathoracic obstruction, expiratory stridor suggests intrathoracic obstruction, and inspiratory and expiratory stridor suggests a fixed obstruction.

- Does the patient wheeze? These are whistling noises caused by turbulent airflow through narrowed intrathoracic airways. The most common cause is asthma.

- Does the breathlessness affect the activities of daily living and quality of life?

- Occupational history, including exposure to dusts or allergies. Dyspnea only during the working week may be suggestive of occupational lung disease.

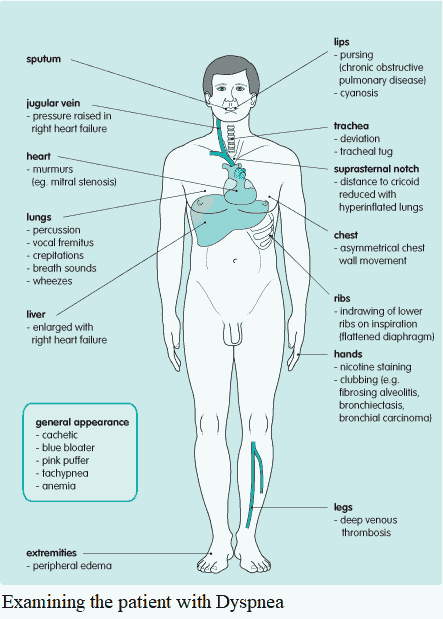

Examining the Patient with Shortness of Breath (Dyspnea)

Inspection

Note the respiratory rate from the end of the bed or while feeling the pulse.

Look for cyanosis; a blue color in the mouth and tongue due to inadequate oxygenation (i.e., 5 g reduced hemoglobin (Hb) per 100 ml of blood). It is commonly associated with lung disease and cardiac disease and hypoventilation from other causes (note that severely anemic patients are not cyanotic-they don’t have enough Hb to break the 5 g/100 ml barrier).

Cyanosis is an unreliable guide to the degree of hypoxemia. Peripheral cyanosis is due to poor peripheral circulation (e.g., in cardiac failure, peripheral vascular disease, or arterial obstruction) and physiologic when due to cold. Cyanosis is rarely seen in anemic patients.

The following factors should also be looked for when assessing the patient with shortness of breath:

- Anemia.

- Clubbing: respiratory causes include carcinoma of the bronchus; pus in any part of the respiratory tract (e.g., empyema, lung abscess, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis; fibrosing alveolitis; chronic suppurative pulmonary tuberculosis; pleural mesothelioma).

- Chest movements on inspiration and expiration: an abnormality is normally found on the side of diminished movements.

- Accessory muscles: patients with COPD typically have overexpansion of the lungs. Because the diaphragm provides less lung expansion, they often rely on chest and neck muscles to respire.

- Barrel-shaped chest: emphysema.

- Kyphoscoliosis: can decrease chest size and expansion.

- Ankylosing spondylitis: can “fix” the chest.

- Rhythm of respiration:

- Cheyne-Stokes respiration describes periods of fast and deep inspiration followed by periods of apnea due to depression of the central respiratory center in the medulla. This may occur with severe chest infections, metabolic acidosis, opiate overdose, and raised intracranial pressure.

- Metabolic acidosis leads to “deep sighing” breathlessness (Kussmaul respiration). Causes include uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, salicylate ingestion, methanol ingestion, and lactic acidosis

Don’t forget to look at the sputum:

- Purulent, moderate quantity-bronchitis or pneumonia.

- Purulent, copious quantity-bronchiectasis or pneumonia.

- Pink and frothy-pulmonary edema.

- Blood-stained-causes of hemoptysis.

- Rust-colored-pneumococcal lobar pneumonia.

Palpation

- Feel for lymphadenopathy secondary to malignant disease or infections.

- Palpate the trachea: displacement may indicate underlying chest disease or cardiac disease.

- Check the movement of the rib cage.

- Feel for tactile vocal fremitus.

- Compare both sides anteriorly and posteriorly.

- Percuss for signs of consolidation.

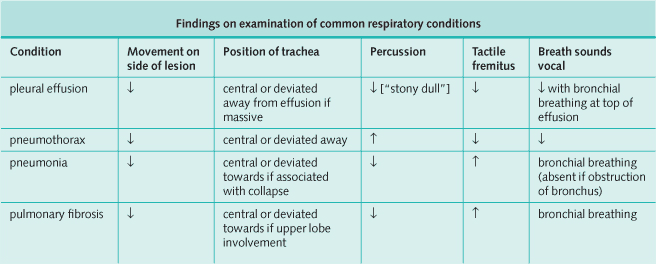

Auscultation

- Expiration: may be prolonged in COPD.

- Bronchial breathing: consolidation, cavitation, or at the top of an effusion.

- Breath sounds: diminished over an effusion, pneumothorax, and in the obese.

- Rhonchi or wheezes: partially obstructed bronchi; found in asthma, bronchitis, and occasionally LVF.

- Crackles (sudden opening of small closed airways): pulmonary congestion (fine crackles in early inspiration); fibrosing alveolitis (fine crackles in late inspiration); bronchial secretions (coarse crackles).

- Friction rub: pleural disease

Investigating the Patient with Shortness of Breath (Dyspnea)

- Complete blood count: anemia leading to breathlessness, leukocytosis in pneumonia.

- Basic metabolic panel: renal failure secondary to dehydration, sepsis, or acidosis, producing breathlessness; hyponatremia of fluid overload.

- D-dimer: if negative in a patient with low probability for having PE, PE is ruled out.

- BNP: can help distinguish between heart failure and pulmonary causes.

- Chest x-ray: examine methodically.

- CT scan: the gold standard for parenchymal disease. CT has been used increasingly to evaluate for PE in patients with structural lung disease. In addition, high-resolution CT scans can be used to evaluate interstitial lung disease.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG):

- S1 Q3 T3 pattern in PE (The classic S1 Q3 T3 pattern on the ECG with pulmonary emboli is rare. The ECG commonly shows sinus tachycardia, but other changes include right bundle-branch block, right ventricular strain, and atrial fibrillation)

- P pulmonale (tall p waves >2.5 mm in lead II) in COPD with cor pulmonale;

- Cardiac conditions leading to breathlessness (e.g., myocardial infarction with consequent pulmonary edema).

- Arterial blood gases: pH, partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide, and hydrogen ion concentration.

- Spirometry: to distinguish between obstructive and restrictive lung pathology, to test reversibility to treatments, and to gauge decline/improvement in patients with pre-existing results.

- Transfer factor (D2 CO) and lung volume.

- Ventilation-perfusion scan: suspected pulmonary emboli.

- Bronchoscopy with or without transbronchial biopsy.

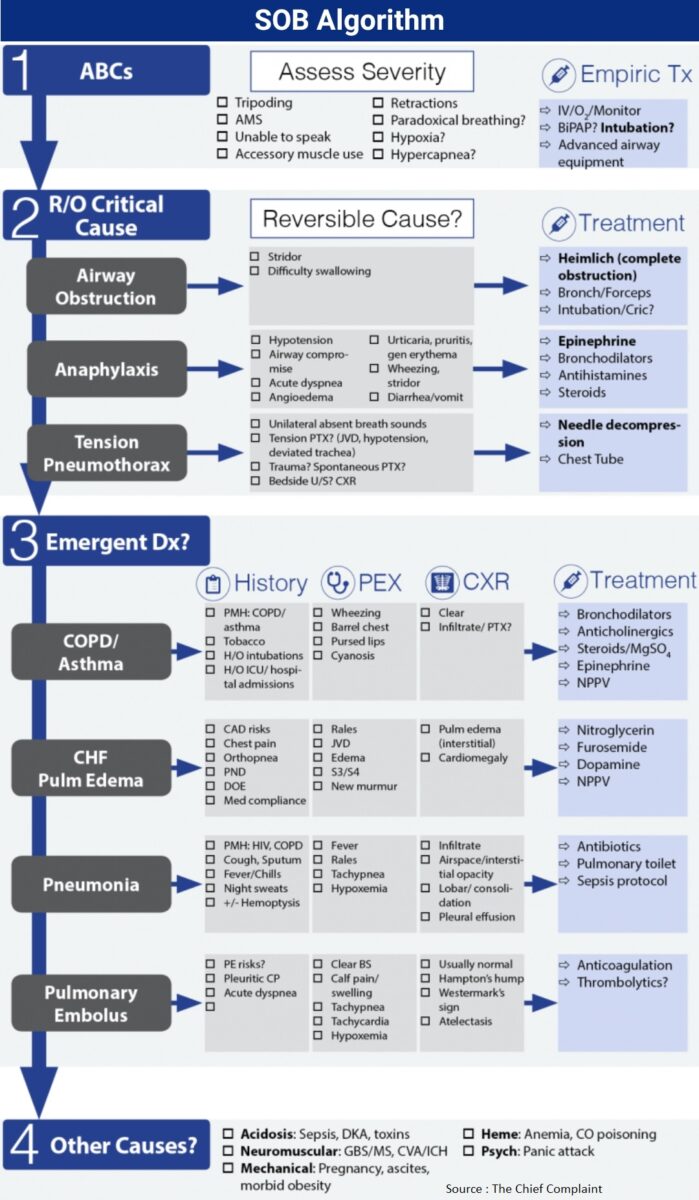

Shortness of Breath Algorithm

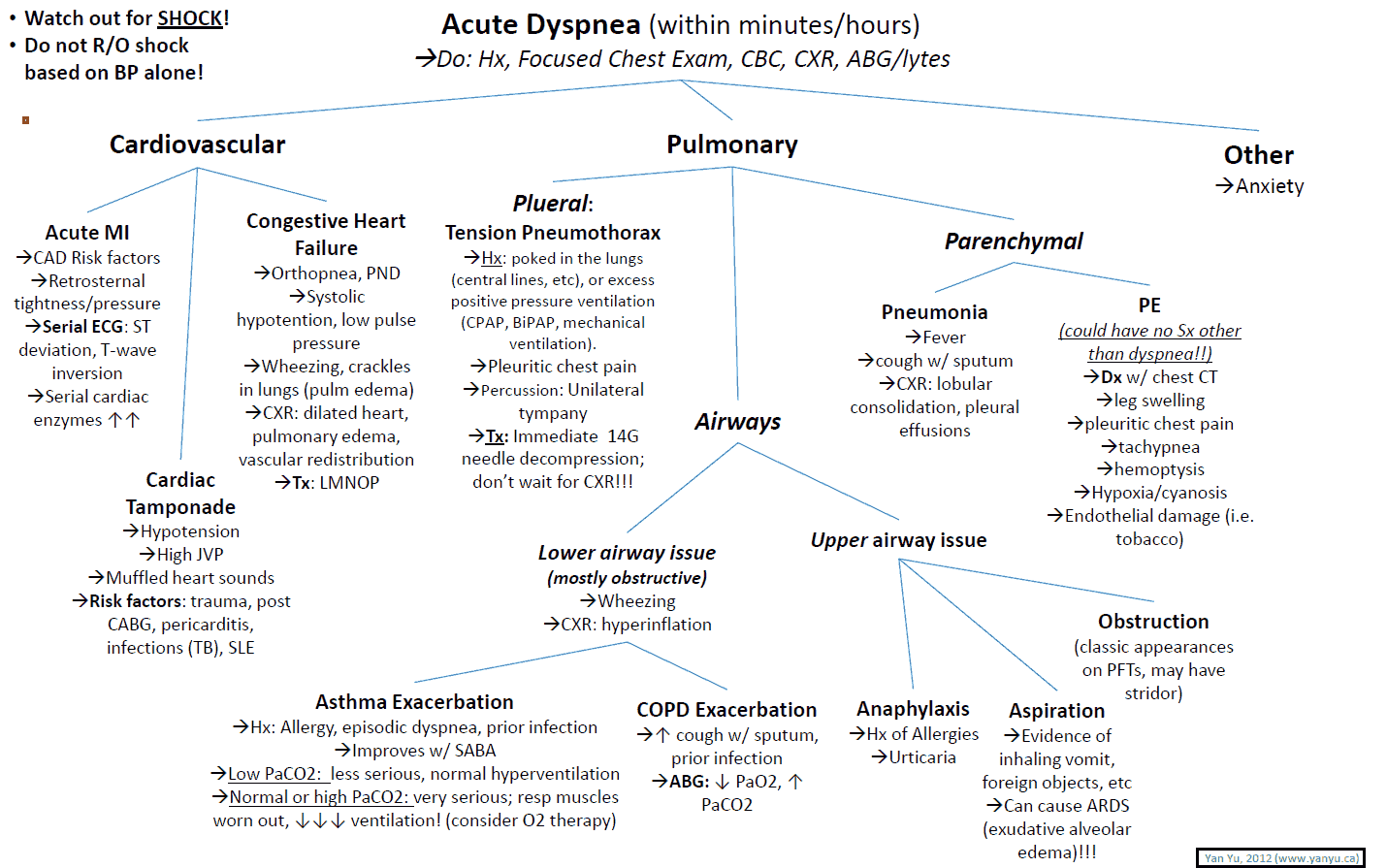

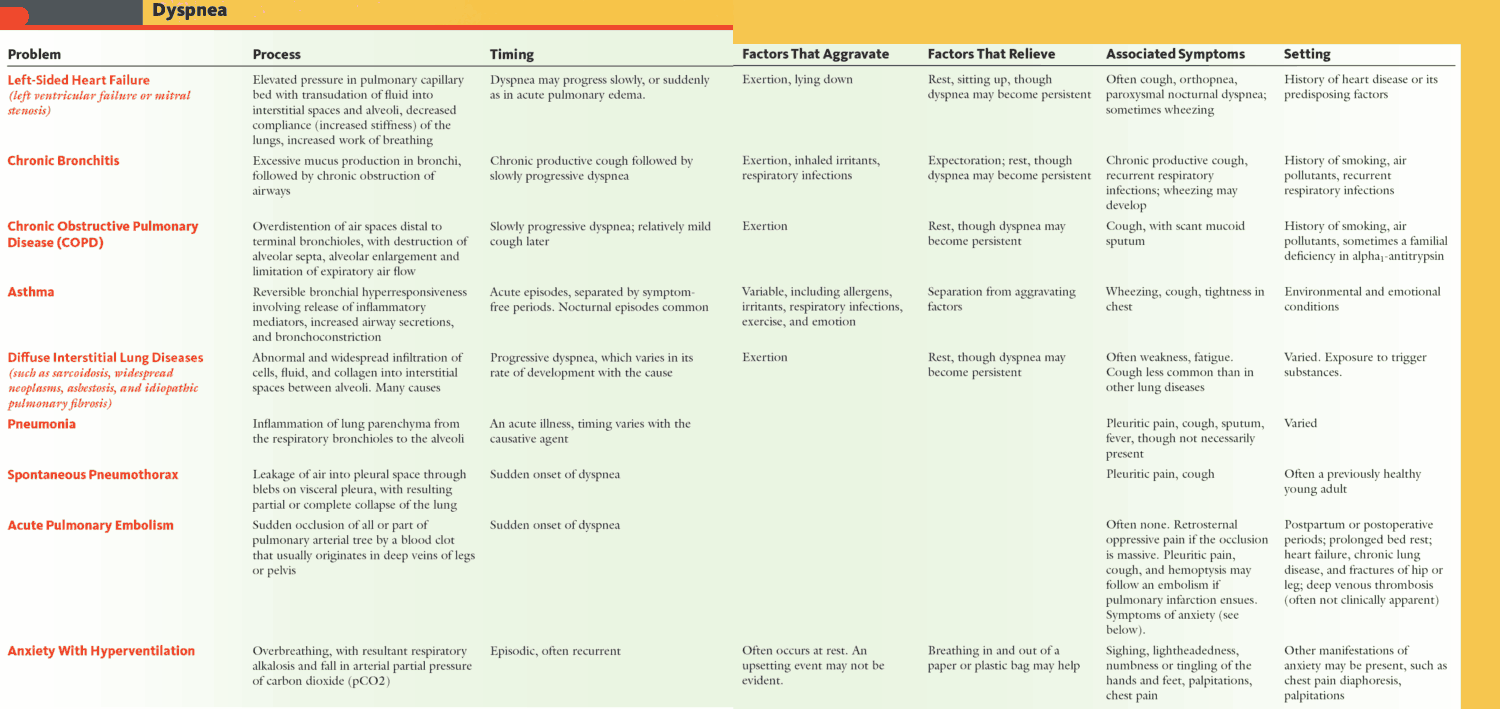

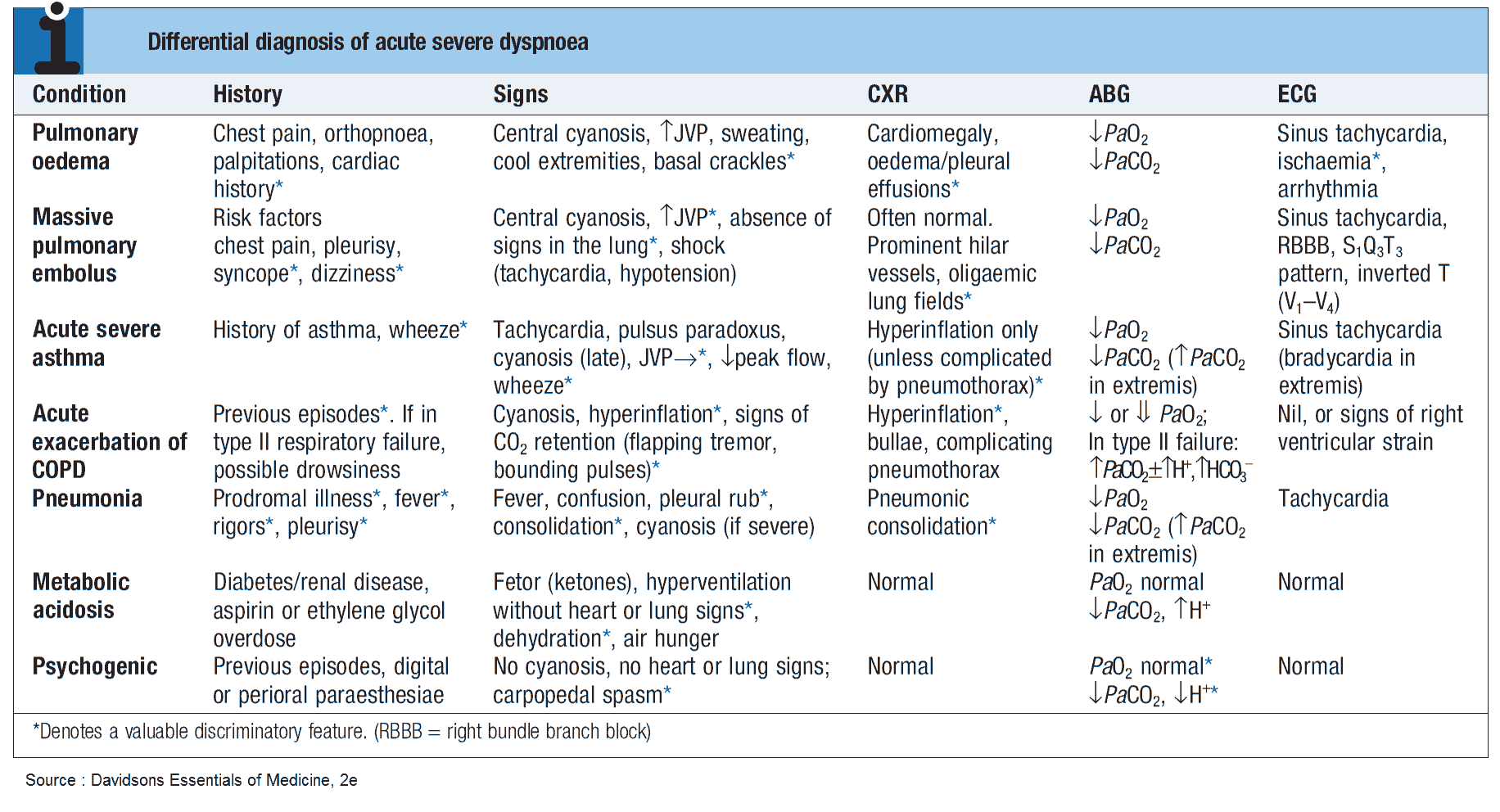

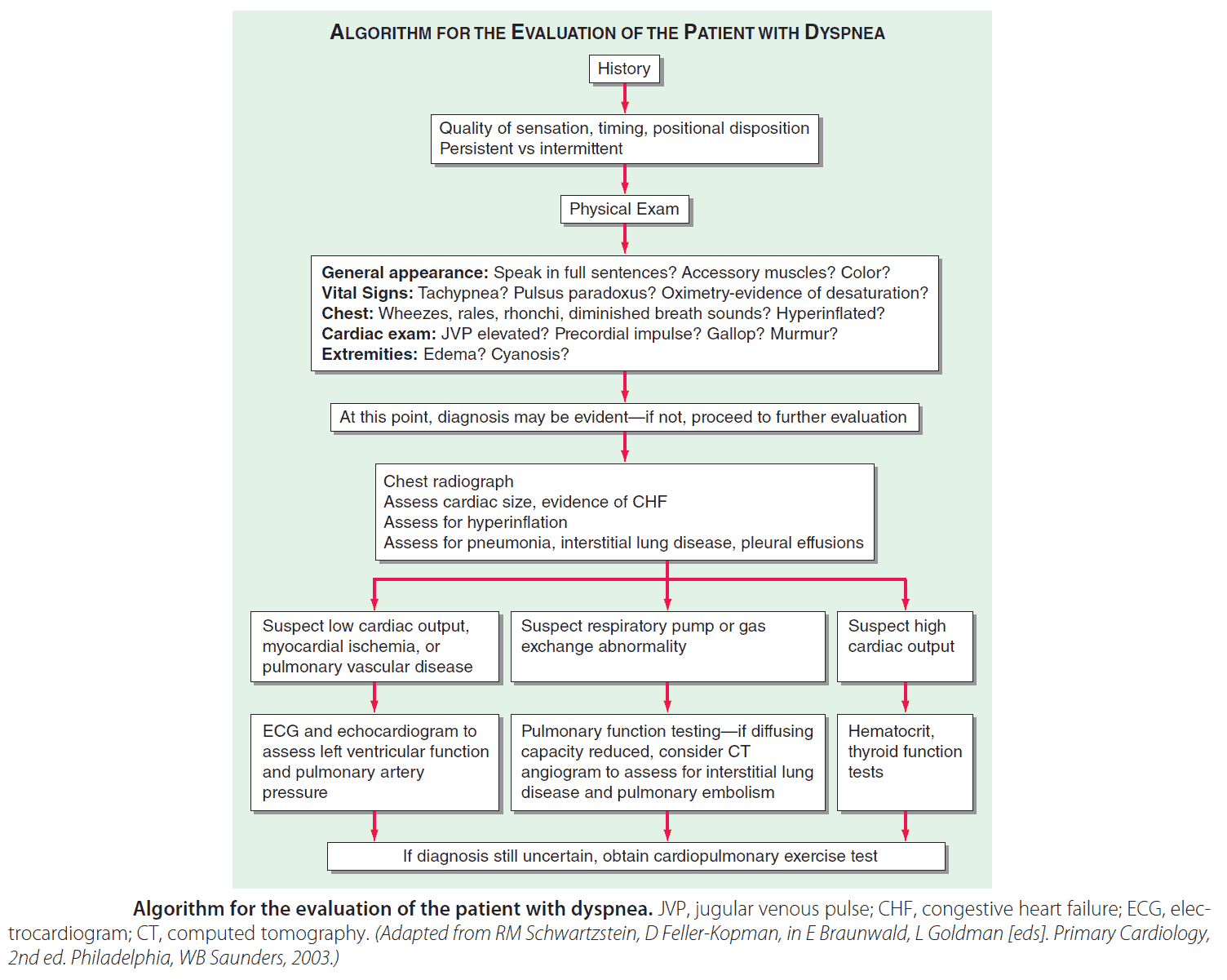

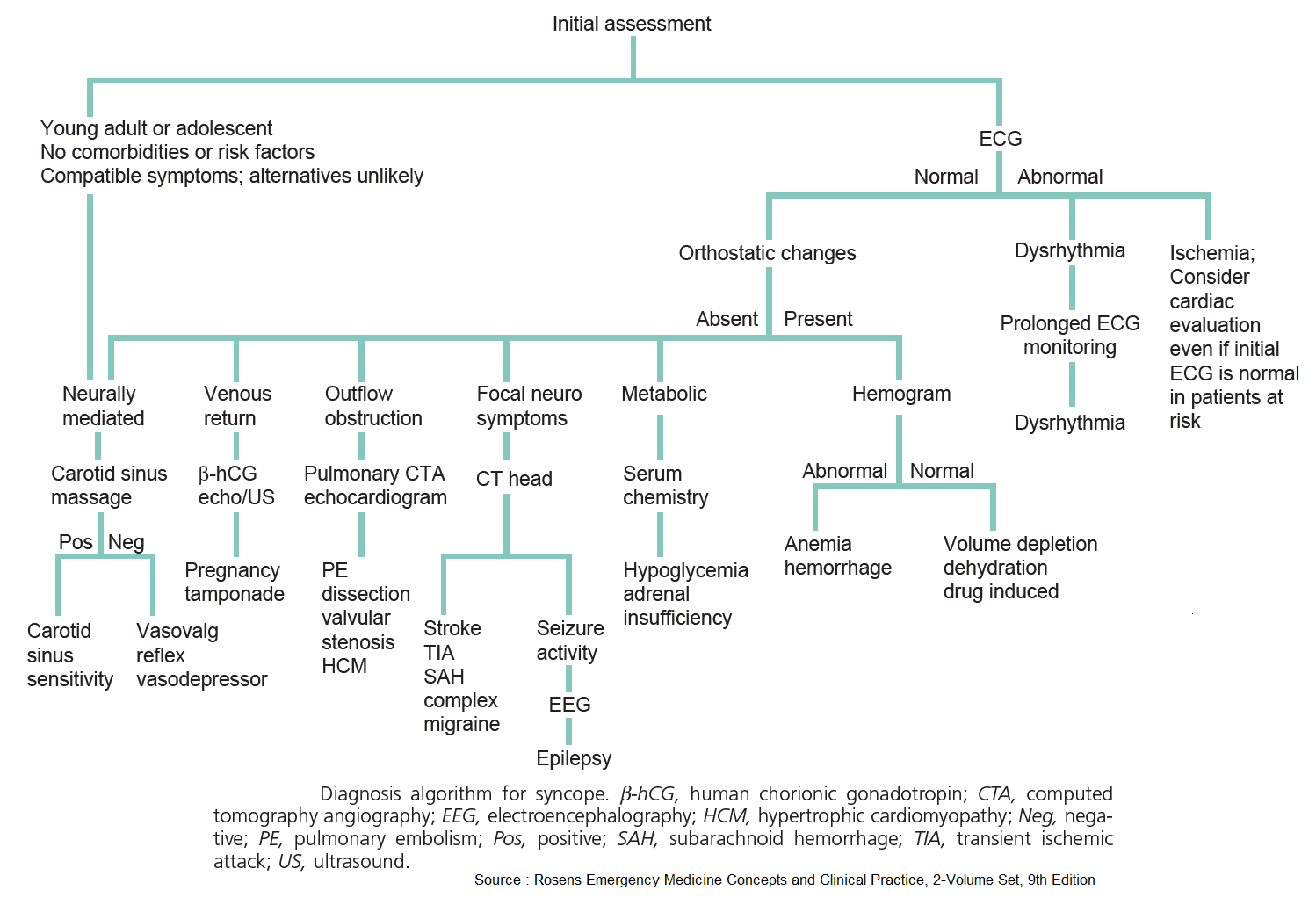

Algorithm for the evaluation of the patient with dyspnea

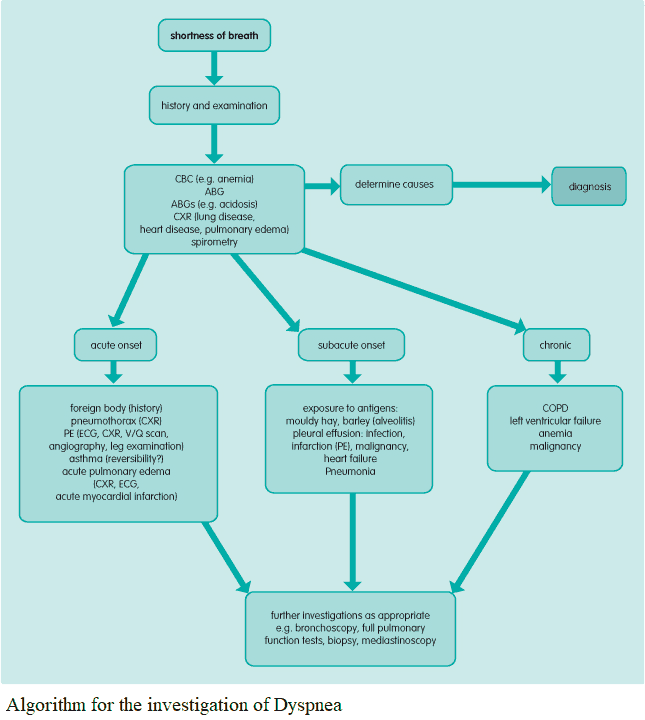

Algorithm for the investigation of Dyspnea

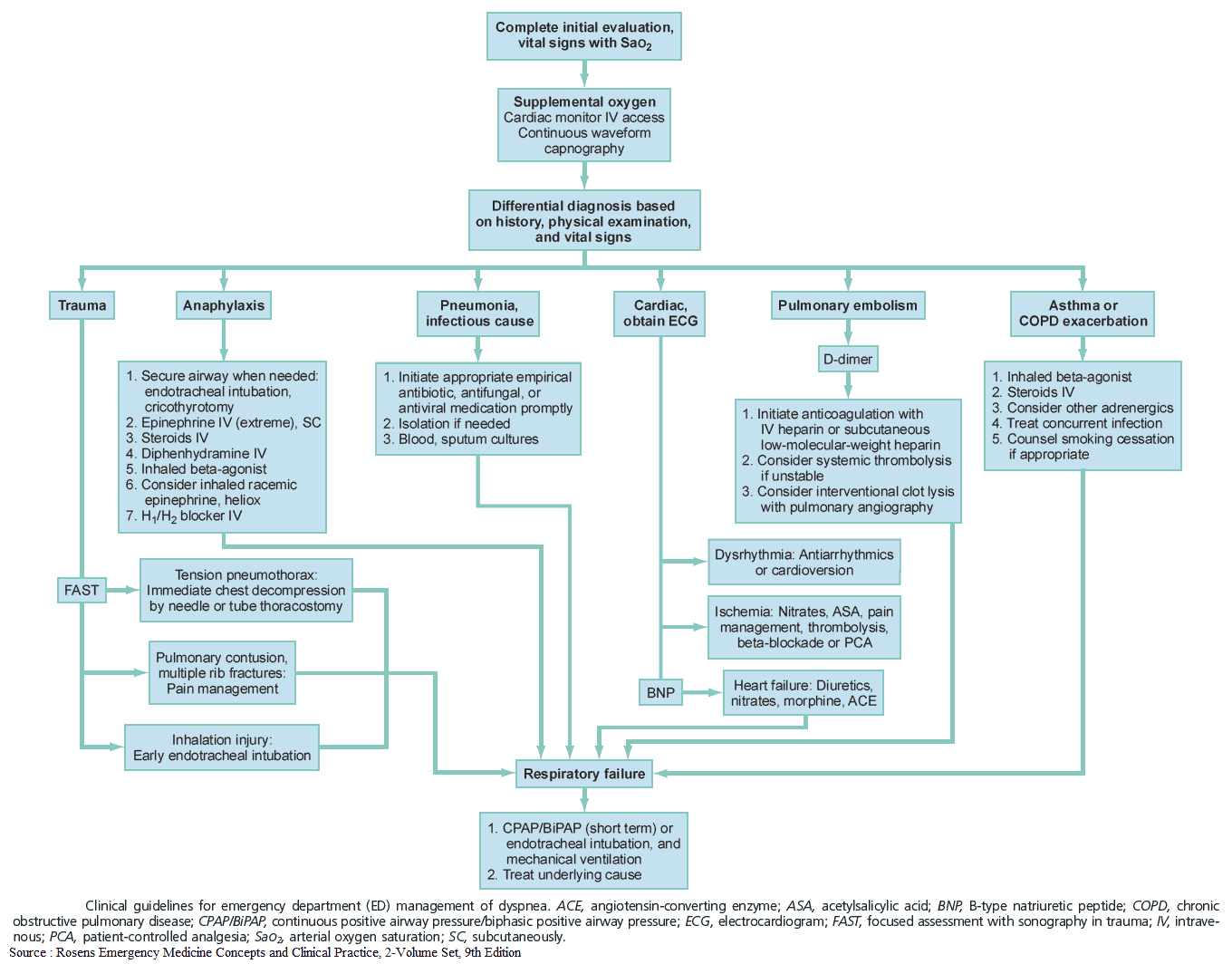

READ ALSO: Shortness of Breath (Dyspnea) in the Emergency Department