Table of Contents

Hemoptysis is the expectoration of blood from a subglottic source. Massive hemoptysis accounts for ~5% to 15% of cases and is often described as more than 600 mL of blood in a 24-hour period.

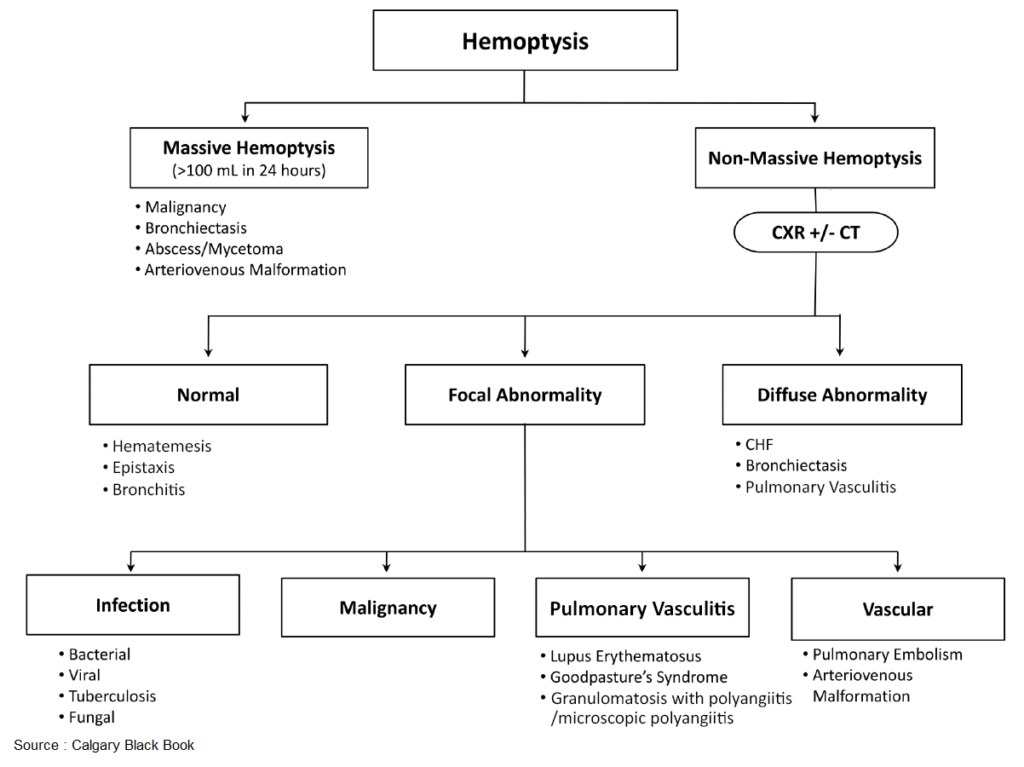

Since the majority of patients do not wait 24 hours to present to the emergency department (ED) after expectorating blood, a more practical definition for massive hemoptysis is the expectoration of more than 100 mL/h or a volume of blood sufficient to impair gas exchange or cause hemodynamic instability. Importantly, the alveoli may contain up to 400 mL of blood before gas exchange is impaired.

Pitfalls in the evaluation of hemoptysis include:

- the failure to identify the source of bleeding (pulmonary versus gastrointestinal)

- failure to appreciate the danger posed by the cause (i.e., pulmonary embolism, bioterrorism agents)

- underestimation of the volume or rate of hemorrhage.

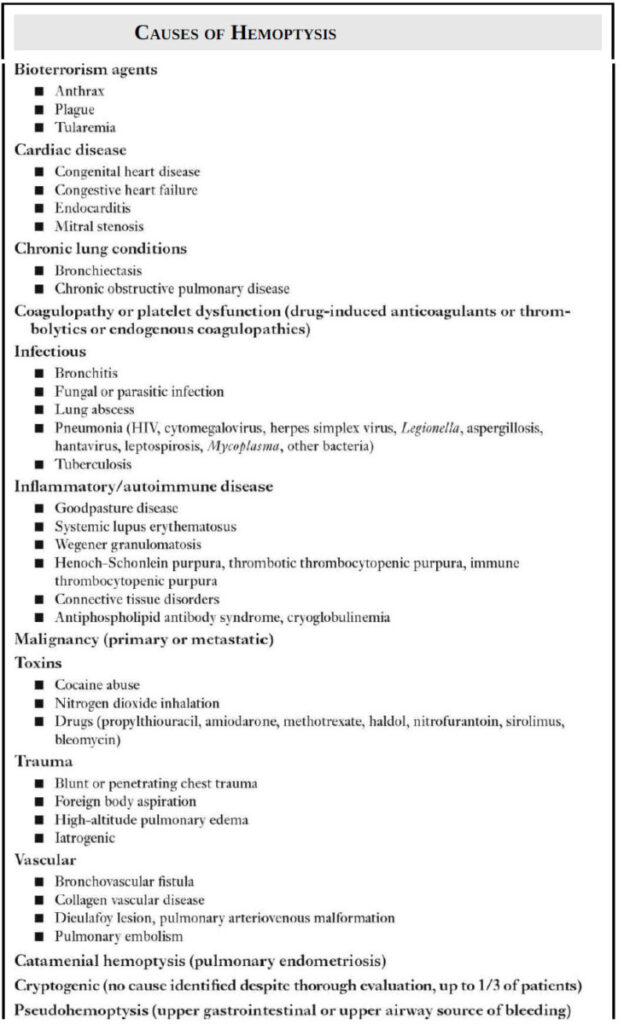

Causes of Hemoptysis

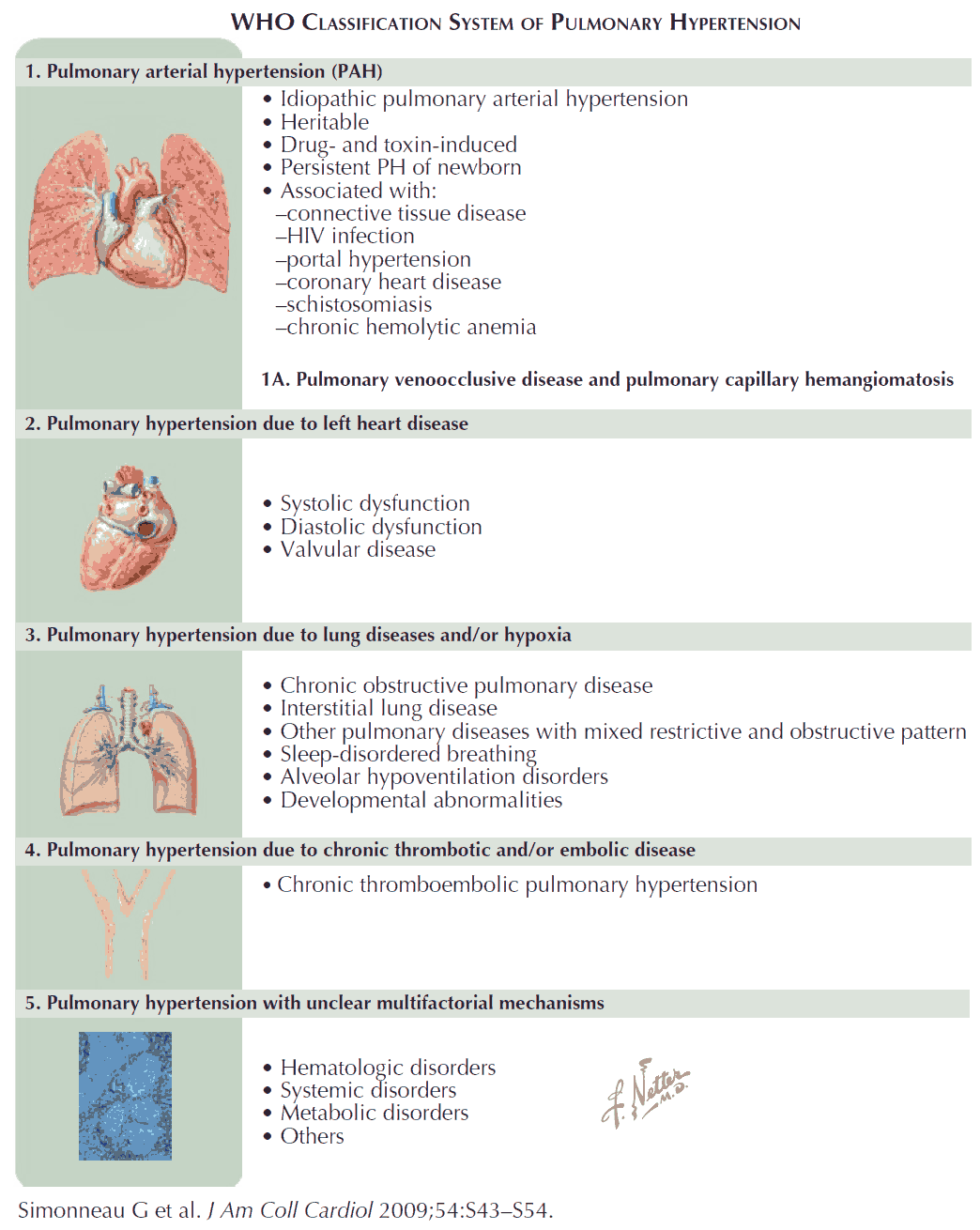

Accurate determination of the precise etiology of hemoptysis is often not possible in the ED; however, knowledge of the most common causes of hemoptysis permits appropriate disposition and management. Bronchitis, bronchiectasis, pneumonia, and tuberculosis account for up to 80% of cases of hemoptysis. Bronchiectasis, pneumonia, bronchogenic carcinoma, and tuberculosis are the most common causes of massive hemoptysis. The sources of bleeding in up to 90% of cases of massive hemoptysis are the bronchial arteries, with the remaining 10% of cases from pulmonary or systemic arteries.

Evaluation of Hemoptysis

Risk Factors

The history of present illness should focus on the identification of risk factors for the most common conditions, such as:

- history of tobacco use

- vasculitis

- immunosuppression

- venous thromboembolism

- tuberculosis

- history of coagulopathy

- use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications

- exposure to toxins

- recent history of chest trauma.

Attempts should be made to quantify the volume of blood expectorated and describe its composition (i.e., gross blood, clots, blood-streaked sputum).

Physical Examination

Key findings on physical examination include:

- the presence of petechiae or ecchymosis

- diastolic murmur consistent with mitral stenosis

- new murmur concerning for endocarditis

- asymmetric lung sounds

- asymmetric extremity edema that suggests deep venous thrombosis.

- The oral and nasal cavities should be inspected for an upper airway source of bleeding.

Nasogastric Aspirate

If the history is insufficient to exclude hematemesis, a nasogastric aspirate can be tested for blood. In addition, the bloody material produced by the patient may be pH tested, with an acidic pH indicative of a gastrointestinal source and an alkaline pH suggestive of a pulmonary source.

Chest x-ray (CXR) and Computed Tomography (CT)

A chest x-ray (CXR) will be abnormal in more than 50% of patients with hemoptysis. Stable patients with a nondiagnostic CXR should undergo computed tomography (CT) of the chest with intravenous contrast. Results of the CT will determine the need for bronchoscopy as well as subsequent management.

Laboratory tests

Laboratory tests depend on the condition of the patient and may include:

- markers of bleeding severity and respiratory failure (i.e., hemoglobin, arterial blood gas)

- studies to diagnose the cause (i.e., coagulation studies, sputum Gram stain, acid-fast bacillus, D-dimer)

- tests to facilitate treatment (i.e., type and cross)

Management of Hemoptysis

Patients with massive hemoptysis are ideally managed at a facility with access to:

- interventional pulmonology (for balloon tamponade, topical hemostatic application, or iced saline lavage)

- interventional radiology (for bronchial artery embolization)

- thoracic surgery (for lobectomy or pneumonectomy if other measures fail)

Arrangements for hospital transfer should be made when it is anticipated that the patient may need these services. Unstable patients require immediate treatment to optimize oxygenation and ventilation and avoid asphyxiation from blood.

Blood product transfusion to correct anemia, optimize hemodynamics, and correct coagulopathy and platelet dysfunction should be pursued early. If the side of bleeding can be determined from the history, exam, or imaging, the patient should be placed in a bleeding-lung-down position in order to exploit gravity and keep blood from spilling into the nonhemorrhagic lung.

In cases of massive hemoptysis that result in respiratory failure, endotracheal or endobronchial intubation should be performed. Use of a size 8.0 tube or larger is desirable to facilitate clot removal and introduction of a flexible bronchoscope. If the side of bleeding has been determined and the bleeding is life threatening, the unaffected lung may be isolated by intubation of that main bronchus.

This is ideally attempted with bronchoscopic guidance. Intubation of the right main bronchus is complicated by occlusion of the right upper lobe bronchus, but is often the quickest and safest solution for left lung hemorrhage. If performed blindly, rotation of the endotracheal tube 90 degrees in the direction of the desired side can aide in correct placement. If this fails, placement of a double-lumen tube or use of bronchial blockers may be considered when available.

The majority of ED patients will have “nonmassive” hemoptysis. Most patients with <~30 mL of blood in 24 hours can be discharged, provided they have normal vital signs, a stable ED course, and no significant comorbid conditions or acute life-threatening conditions. Most importantly, timely referral and follow-up should be arranged.

Key Points

- Carefully inspect the oral and nasal cavities to evaluate for an upper airway source of bleeding.

- Consider nasogastric aspirate and pH testing of the material to differentiate hematemesis from hemoptysis.

- Patients with massive hemoptysis should ultimately be managed at a facility with interventional pulmonologists, interventional radiologists, and thoracic surgeons.

- If identified, the bleeding lung should be placed in a dependent position.

- In cases of life-threatening massive hemoptysis, intubation of the main bronchus of the nonbleeding lung with a size 8.0 or larger tube should be attempted.