Table of Contents

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) results from a variety of conditions that can vary from annoying to life threatening. The determination of nonvariceal versus variceal bleeding is critical as the tests and treatments vary depending on the etiology. Acute variceal hemorrhage (AVH) is the most common etiology of UGIB in patients with cirrhosis. It accounts for roughly 50% of cases and is associated with a mortality rate as high as 20%.

Cirrhosis causes fibrotic changes in the hepatic parenchyma that decrease hepatic vascular compliance and increase portal vascular resistance. This in turn leads to dilatation of collateral vessels located at the gastroesophageal junction, that is, varices.

Presentation

- Patients with a history of alcohol abuse, known cirrhosis, or a history of varices presenting with a UGIB should be presumed to have variceal bleeding and treated as such.

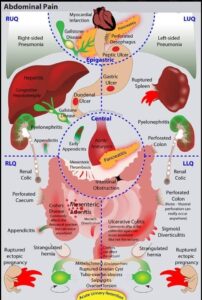

- Initial history taking should focus on the amount and route of hemorrhage. For hematemesis, is it coffee-ground or bright red? For blood by rectum, is it melena or hematochezia?

- Ask about other risk factors for UGIB such as a history of gastric/esophageal varices, use of anticoagulants and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and other comorbidities that may affect the patient’s ability to cope with acute blood loss.

- Symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, pallor, decreased urine output, or confusion may portend worsening end organ perfusion and shock.

Stabilization

- Given their potential to decompensate quickly, patients require large-bore intravenous access and close monitoring.

- Large-volume hematemesis, altered mental status, and hemodynamic instability are indications for early airway management due to risks of aspiration and to facilitate endoscopy.

- Circulatory collapse in the case of a brisk hemorrhage should be addressed with crystalloids and blood products with a target hemoglobin >7 g/dL (potentially higher transfusion targets for those at risk of end organ dysfunction).

- Plasma or prothrombin complex concentrates (PCC) and platelets should be given to correct coagulopathy with a goal INR <1.8 and platelets >50,000. However, remember, in rapid blood loss, there will be significant delay in the fall of the measured hemoglobin concentration, so treat the patient’s hemodynamic and perfusion status, not the numbers from the laboratory!

Laboratory studies may include:

- Complete blood count (blood loss, platelets)

- Coagulation factors (hepatic synthetic function)

- Liver function tests (indication of hepatic dysfunction)

- Basic metabolic panel (elevated BUN from blood in the alimentary canal and renal function)

- Creatinine (renal function)

- Type and cross (transfusion)

Bedside tests such as nasogastric lavage (NGL) and stool guaiac testing have classically been utilized in assessing an upper GI bleed. The utility of NGL, however, is questionable in all but the most severe cases of UGIB, and it causes great discomfort to patients.

Treatment

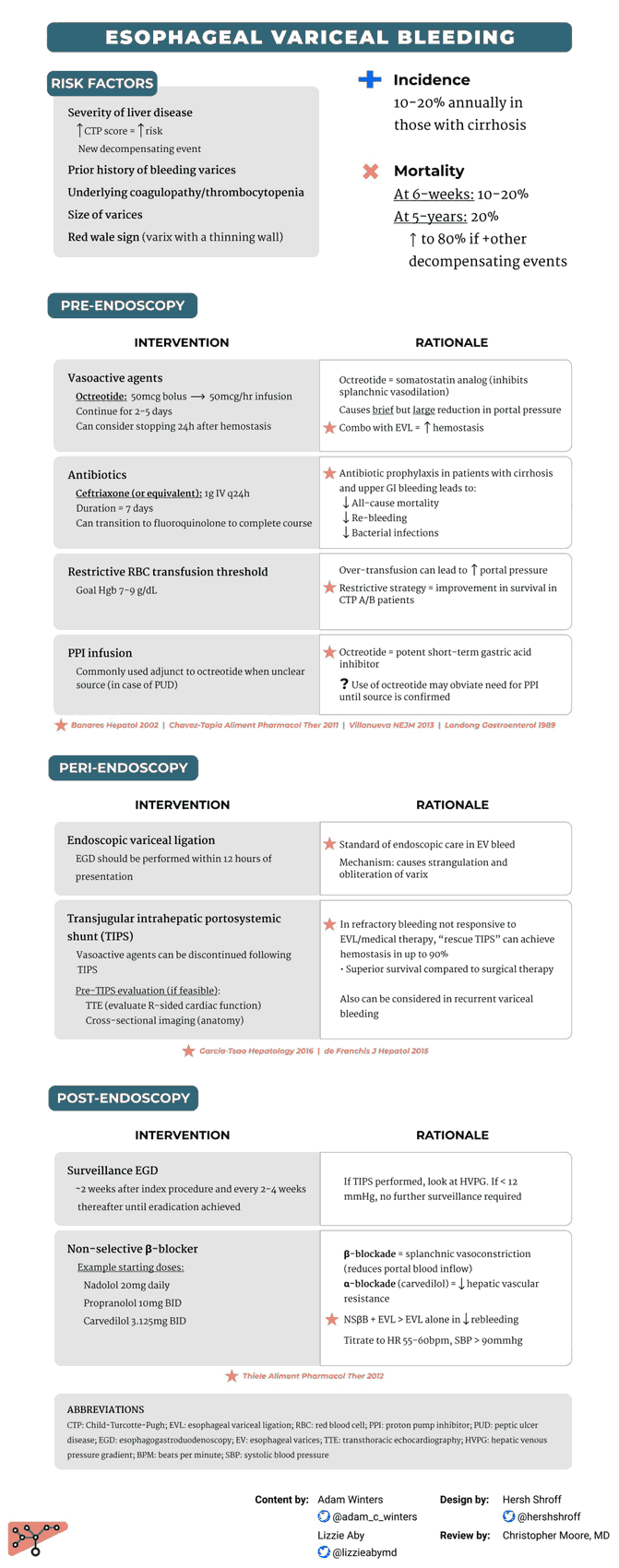

Pharmacologic interventions for variceal bleeding include the use of:

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

- Somatostatin analogs (octreotide)

- Antibiotics (ceftriaxone).

PPIs are commonly used empirically in the cirrhotic with UGIB because brisk bleeding from peptic ulcer disease is also quite common. Current guidelines recommend a bolus of 80 mg of pantoprazole with an infusion of 8 mg/hour, but a recent meta-analysis in 2014 showed that intermittent bolus dosing was noninferior to bolus plus infusion for bleeding ulcers.

Somatostatin analogues (namely, octreotide in the United States) are recommended to treat variceal bleeds to reduce portal hypertension. Octreotide is given as a bolus dose of 25 to 50 mcg IV with an infusion of 25 to 50 mcg/hour. To date, studies show an increased rate of early hemostasis and 5-day hemostasis but no change in adverse events nor a decrease in mortality.

Prophylactic antibiotics (commonly ceftriaxone 1 g IV) should be given to all acute variceal bleeds because they confer a mortality benefit in addition to decreasing rebleeding and hospital length of stay.

Consultation and Disposition

- Early consultation with the gastroenterology service is recommended for immediate endoscopy, given that only 50% of variceal bleeding will stop on its own.

- Most patients with AVH will require ICU admission, indications include:

- Need for emergent endoscopy

- Hemodynamic instability or altered mental status

- Evidence of active bleeding (hematemesis or large bloody lavage)

- Significant comorbidities (coronary artery disease, cancer, alcohol withdrawal, etc.).

- Patients who fail endoscopic therapy may benefit from emergent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) to reduce portal pressure and achieve hemostasis.

- Finally, in the case of the unstable patient without access to immediate endoscopy, balloon tamponade can be employed as a temporizing measure after the patient has been orotracheally intubated. Each commercially available balloon device has its own particular requirements for placement. The Sengstaken-Blakemore and Minnesota tubes have both a gastric balloon and an esophageal balloon. The Linton-Nachlas tube has only a single gastric balloon, which is usually sufficient to provide local tamponade of bleeding from gastroesophageal variceal bleeding. Complications can be severe and include esophageal rupture, airway obstruction, or aspiration pneumonia; however balloon tamponade is potentially lifesaving when other options are unavailable.

Key Points

- All patients with cirrhosis presenting with UGIB should be presumed to have AVH.

- These patients are sick and often require early advanced airway management and resuscitation with multiple blood products.

- Endoscopic therapy (consult GI early) + medical therapy (PPI, octreotide, and ceftriaxone) are first-line treatment.

- Consider TIPS or balloon tamponade for uncontrolled bleeding.