Table of Contents

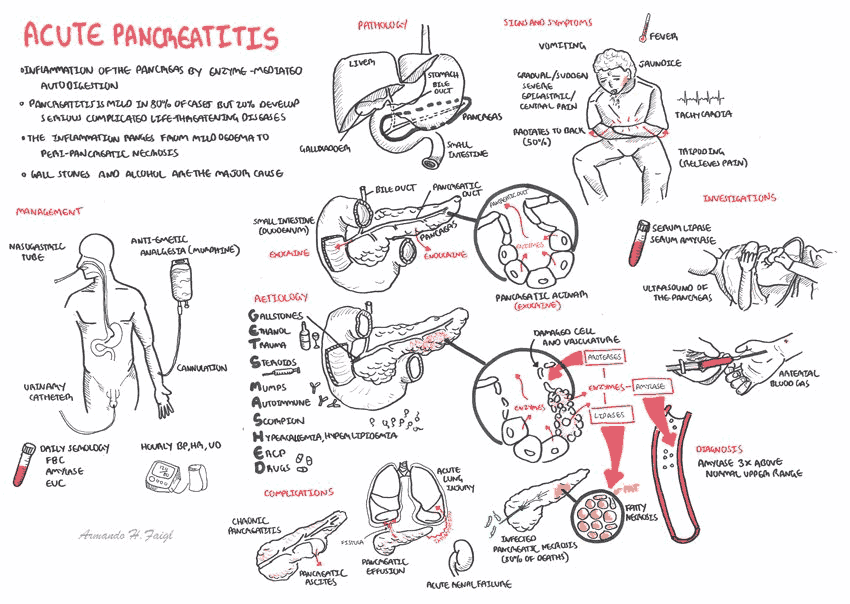

Acute pancreatitis is frequently encountered in the emergency department (ED) and results in hospital admission around 65% of the time in the United States.

Many scoring systems have been developed to assess prognosis and severity of acute pancreatitis, often incorporating CT and MR imaging of the abdomen.

However, this imaging is most beneficial later in the inpatient hospitalization rather than during the acute ED evaluation, unless the diagnosis is in question. Therefore, discretion should be used when ordering abdominal imaging for patients with a secure diagnosis of acute pancreatitis at the initial presentation.

Symptoms and Presentation of Acute Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis is common in the ED, but the presentation may be variable. Patients may suffer recurrent bouts and could be well known to ED staff with loud complaints of unmanaged pain and nausea while eating Flamin’ Hot Cheetos® in the waiting room. Other patients may suffer more indolent symptoms that can be difficult to differentiate from dyspepsia.

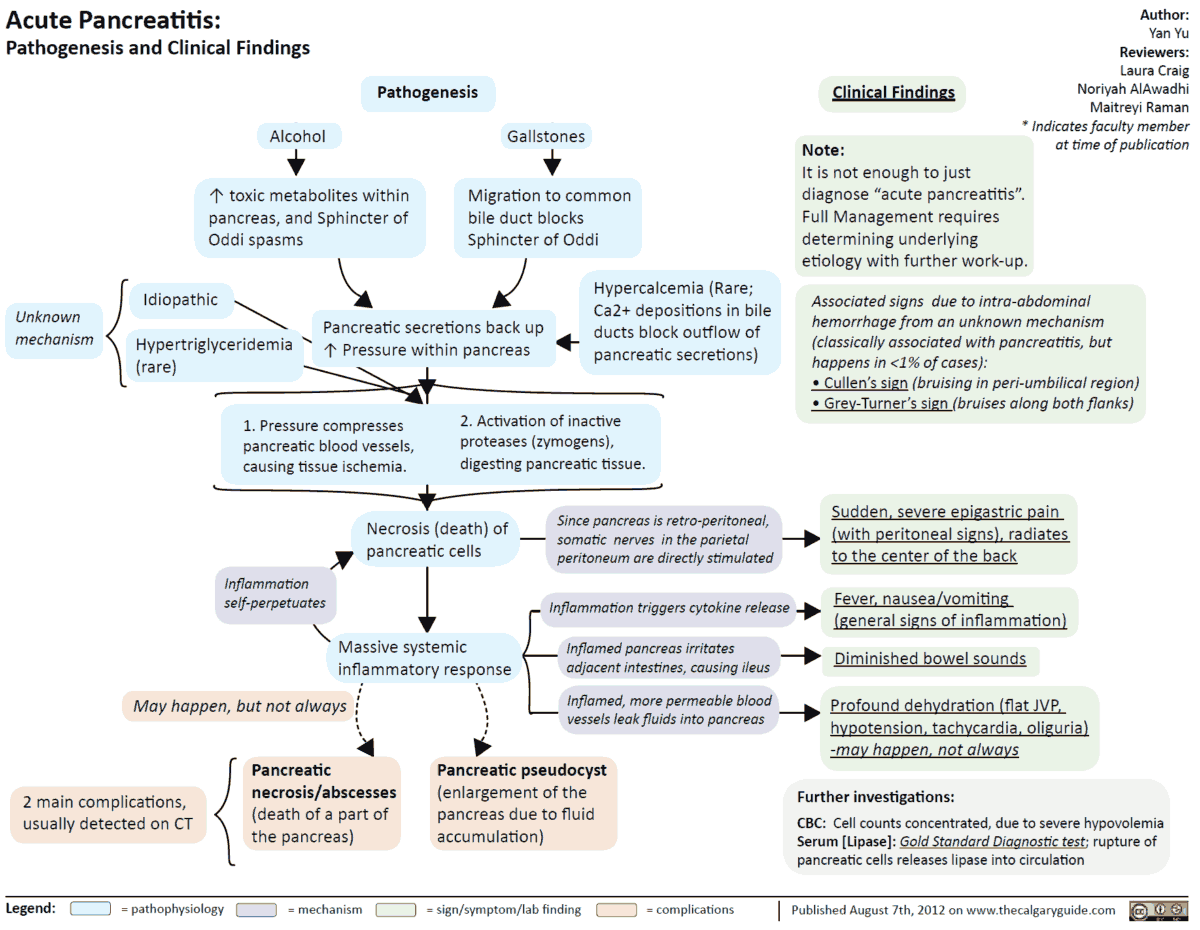

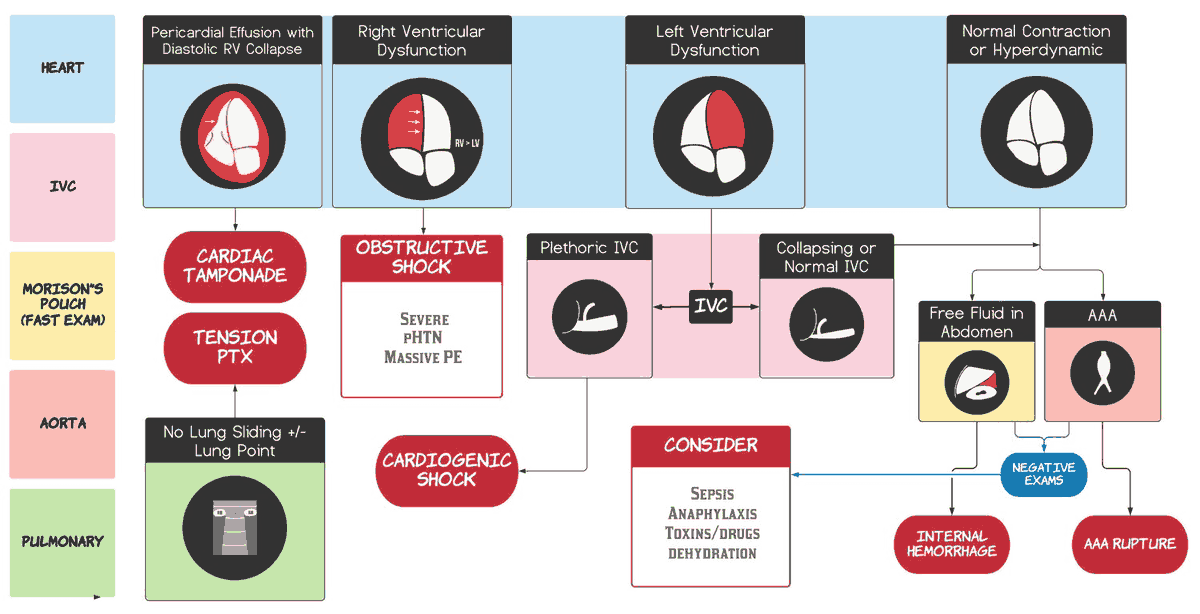

Severe acute pancreatitis can mimic sepsis due to severe inflammation, and patients may present with fever and shock due to extensive third spacing of intravascular volume.

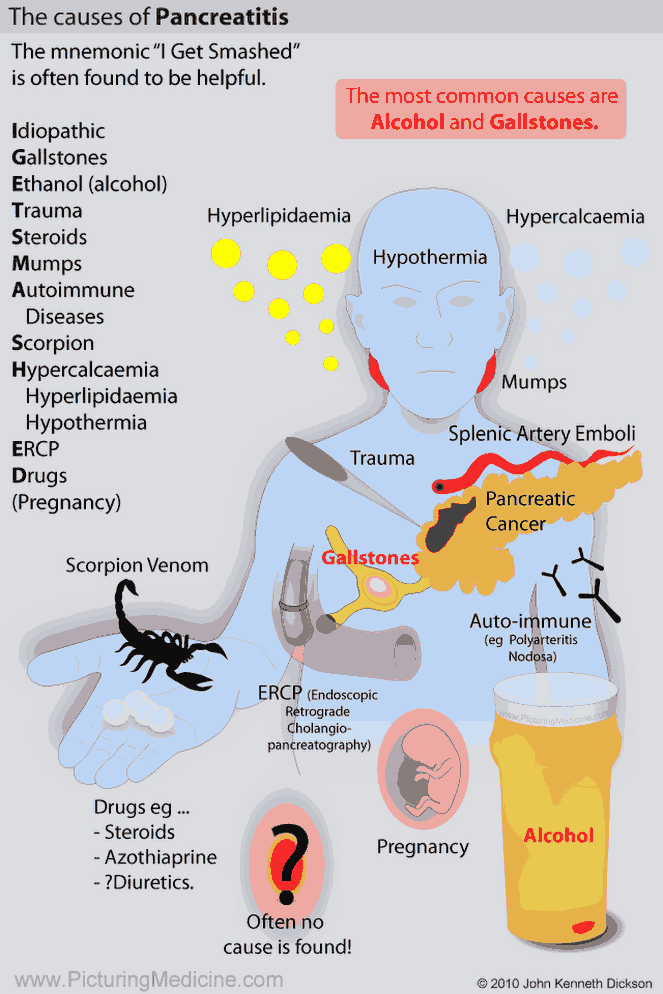

The most common etiologies of acute pancreatitis, gallstones, and alcohol consumption should be elicited as possible triggers.

READ ALSO: Recognizing and Treating Severe Acute Pancreatitis (SAP)

Utility of Imaging Acute Pancreatitis for Diagnosis

Serum lipase levels have excellent sensitivity and specificity for pancreatitis in the acute phase of illness, approaching 95% in the first two days of symptoms. However, serum lipase level becomes more unreliable in patients with chronic or intermittent pancreatitis.

- In patients with typical symptoms and diagnostic laboratory tests, CT or MR imaging is not required to confirm the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

- To determine the underlying cause, biliary imaging, typically by ultrasound, and social history for alcohol use are critical first steps.

- When the diagnosis is unclear due to equivocal laboratory findings and atypical presentation, CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis may be indicated to assess for nonpancreatic causes of abdominal pain or to verify pancreatic inflammation confirming an acute pancreatitis diagnosis.

Utility of Imaging Acute Pancreatitis and it’s Complications for Intervention and Prognosis

CT or MR imaging for acute pancreatitis is primarily used to detect complications such as pancreatic necrosis or fluid collections (pseudocysts) that may warrant interventional drainage. However, these findings are typically delayed by at least several days after the onset of symptoms. Moreover, the initial management of pancreatitis is supportive.

When complications are detected on imaging, intervention is usually delayed until a week or longer after diagnosis and is reserved for fluid collections with mature cyst walls that do not resolve spontaneously or pancreatic necrosis with associated infection.

While the optimal timing of imaging is unclear, it is generally recommended that the optimal timing of imaging for patients with persistent symptoms or fever to be after 48 to 72 hours of medical management.

Boarding times in the ED seldom approach these thresholds, so CT or MR imaging is not typically indicated in the ED for the patient with an established diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

Hazards of Imaging Patients with Acute Pancreatitis

A recent retrospective study at an academic hospital found that over half of all patients presenting to the ED with acute pancreatitis underwent CT imaging in the first 24 hours of admission; the vast majority of these patients had a clear diagnosis of acute pancreatitis without this imaging. Other studies have also demonstrated increasing rates of early or ED-based imaging of acute pancreatitis nationwide.

Projections of radiation risk are dependent on many factors, but modeling predicts a number needed to harm of roughly 1,000 abdomen/pelvis CT exposures in healthy 40-year-old patients for each radiation-induced cancer.

Detection of clinically insignificant lesions elsewhere in the abdomen that require additional invasive testing or repeat imaging (so-called incidentalomas) confers additional risk to the patient and draws excess resources and cost from the health care system.

While early CT or MR imaging may be occasionally necessary in very ill patients or in cases where there is diagnostic uncertainty, routine imaging is seldom useful and potentially harmful. Be judicious with the radiation exposure risk of excess CT imaging.

Key Points

- CT/MR imaging is not indicated for assessment of clear-cut acute pancreatitis in the ED.

- Serum lipase levels are unreliable in patients with chronic or intermittent pancreatitis.

- Excess imaging carries real risk to the patient.

- Consider cross-sectional imaging (CT and MRI) to assess for nonpancreatic causes of abdominal pain if the diagnosis is unclear.

- CT or MR imaging are primarily used to detect complications of acute pancreatitis.

- Optimal timing for imaging patients with acute pancreatitis with persistent symptoms or fever is after 48 to 72 hours of medical management.

References / Suggested Readings

- Bharwani N, Patel S, Prabhudesai S, et al. Acute pancreatitis: The role of imaging in diagnosis and management. Clin Radiol. 2011;66:164–175.

- Dachs RJ, Sullivan L. Does early ED CT scanning of afebrile patients with first episodes of acute pancreatitis ever change management? Emerg Radiol. 2015;22:239–243.

- Shinagare AB, Ip IK, Raja AS, et al. Use of CT and MRI in emergency department patients with acute pancreatitis. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:272–277.

- Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2078–2086.

- Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, et al. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: Management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400–1415.