Table of Contents

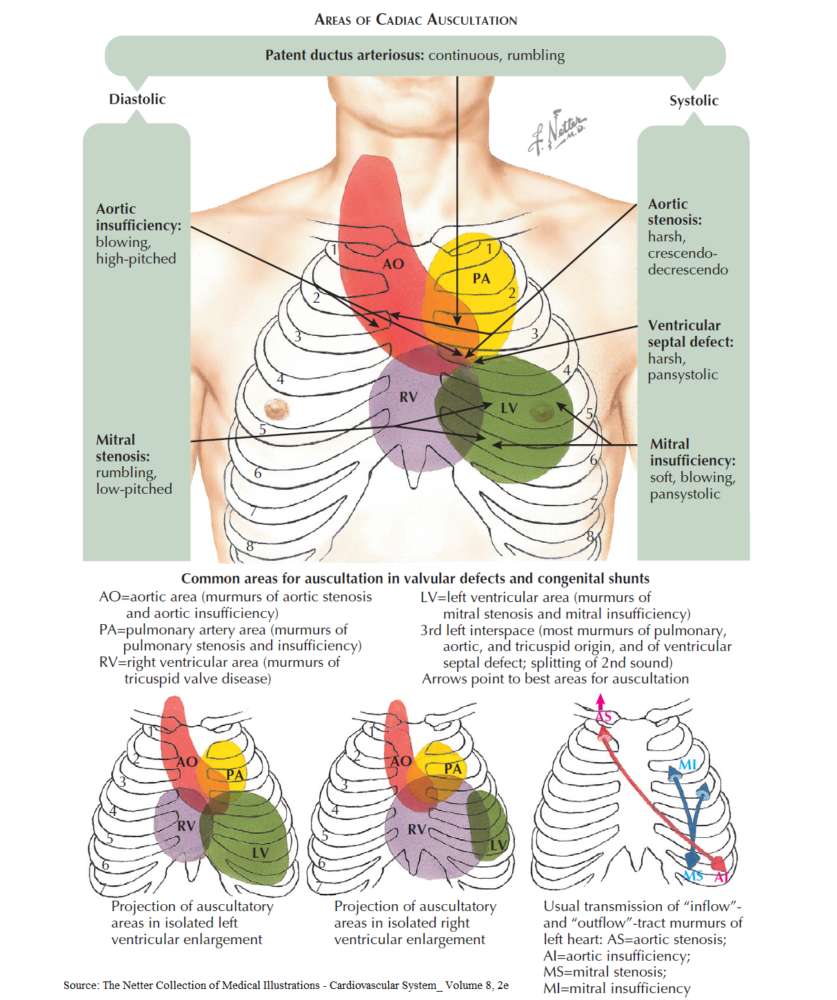

Heart murmurs are due to vibrations caused by turbulent flow within the heart. The most common causes are due to left-sided valvular heart disease and tricuspid regurgitation.

Nonvalvular causes of heart murmur include:

- Innocent “flow” murmurs, especially in children.

- High-output states (e.g., pregnancy, thyrotoxicosis, and fever).

- Congenital heart disease, such as atrial septal defects (ASD), ventricular septal defects (VSD), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), and coarctation of the aorta.

Differential Diagnosis of Heart Murmurs

- Ejection systolic murmurs

- Holosystolic murmurs

- Diastolic murmurs

- Continuous murmurs

1. Ejection Systolic Murmurs

These usually originate in the right or left ventricular outflow tracts. They reach a crescendo in mid-systole and die down before the second heart sound.

Causes of ejection systolic murmurs in the aortic area (second right intercostal space) include the following:

- Supravalvular (e.g., supra-aortic stenosis or coarctation of the aorta).

- Valvular (e.g., aortic stenosis or aortic sclerosis).

- Subvalvular (e.g., hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy).

- Hyperkinetic states due to increased flow across the valves.

Causes of ejection systolic murmurs in the pulmonary area (second left intercostal space) include the following:

- Supravalvular (e.g., pulmonary arterial stenosis).

- Valvular (e.g., pulmonary valve stenosis).

- Subvalvular (e.g., infundibular stenosis).

- Flow murmurs, hyperkinetic states, and left-to-right shunts (e.g., ASD).

Causes of ejection systolic murmurs at the apex include flow murmurs and aortic stenosis (radiation from the aortic area).

2. Holosystolic Murmurs

These murmurs are of uniform intensity and are heard throughout systole, merging with the second heart sound. Causes of holoystolic murmurs at the lower left sternal edge include tricuspid regurgitation and VSD, and causes of those at the apex include mitral regurgitation.

3. Diastolic Murmurs

These are never normal or physiologic.

Causes of early diastolic murmurs at the left sternal edge include aortic regurgitation and pulmonary regurgitation.

Causes of mid-diastolic murmurs include tricuspid stenosis and increased flow across a nonstenotic tricuspid valve (e.g., ASD and tricuspid regurgitation).

Causes of diastolic murmurs at the apex include the following:

- Mitral stenosis.

- Carey Coombs murmur (due to thickening of mitral valve leaflets in acute rheumatic fever).

- Austin Flint murmur (due to fluttering of the anterior mitral valve cusp in aortic regurgitation by the regurgitant stream).

- Increased flow across a nonstenotic mitral valve (e.g., VSD and mitral regurgitation).

- Graham Steell murmur: pulmonary regurgitation secondary to pulmonary hypertension (also heard at left sternal edge).

4. Continuous Murmurs

Continuous murmurs are heard during systole and diastole, such as in:

- PDA

- coronary arteriovenous fistula

- ruptured aneurysm of the sinus of Valsalva

- cervical venous hum

- ASD with mitral stenosis

History in the Patient with Heart Murmurs

There are no symptoms of cardiac murmurs per se. Therefore, the history should focus on possible causes of the murmur or consequences of the responsible lesion.

Ask about the following:

- Rheumatic fever: particularly affecting the mitral valve.

- Ischemic heart disease (e.g., mitral regurgitation). Due to papillary muscle damage or heart dilation.

- Congenital heart disease.

- Hypertension: flow murmurs.

- Family history: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition.

- Aortic regurgitation (AR) may be associated with rheumatoid arthritis or seronegative arthropathies (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, colitic and psoriatic arthropathy, Marfan’s syndrome, syphilitic aortitis, or coarctation of the aorta). If you suspect any of these, question further about joint symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, neurologic symptoms, etc. In addition, AR is much more common in patients with a known bicuspid valve.

- Mitral regurgitation may be caused by connective tissue disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis), ankylosing spondylitis, or congenital conditions (e.g., Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, or osteogenesis imperfecta).

- Social history: drug and alcohol use may predispose to dilated cardiomyopathy. IV drug abuse suggests infective endocarditis, and smoking is a risk factor for CAD.

- Risk factors for endocarditis, especially a history of rheumatic fever (particularly affecting the mitral valve) or prior infective endocarditis; prosthetic heart valves; recent dental, GI, or respiratory invasive procedures; or known valvular damage.

Symptoms and Consequences of Heart Murmurs

- None: aortic valve disease and mitral regurgitation may remain asymptomatic for years.

- Fatigue and weakness: low cardiac output.

- Palpitations: especially atrial fibrillation.

- Angina: especially in coronary heart disease or aortic stenosis.

- Symptoms of right ventricular failure (secondary to pulmonary hypertension): congestion may result in anorexia, ankle and leg swelling, and hepatic pain.

- Symptoms of left ventricular failure: shortness of breath on exertion, cough and hemoptysis (especially mitral stenosis), orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND).

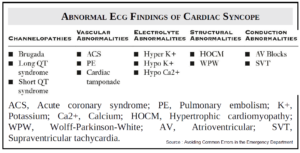

- Syncope due to poor cardiac output in conditions obstructing the outflow tract (e.g., severe aortic stenosis).

- Symptoms of systemic emboli (e.g., transient ischemic attacks or stroke); often a complication in mitral stenosis.

- Symptoms of enlarged left atrium pressing on other structures (especially in mitral stenosis), such as recurrent laryngeal nerve leading to hoarseness (Ortner’s syndrome), esophagus leading to dysphagia, left main bronchus leading to left lung collapse.

- Symptoms of infective endocarditis: fever, malaise, weight loss.

In patients with pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary edema may be precipitated by the following:

- Onset of uncontrolled atrial fibrillation

- Chest infection

- Anesthesia

- Exercise

- Pregnancy

Examining the Patient with Heart Murmurs

Always follow the examination routine-inspection, palpation, then auscultation. Many clues can be gained about the nature of the murmur before the stethoscope is placed on the chest.

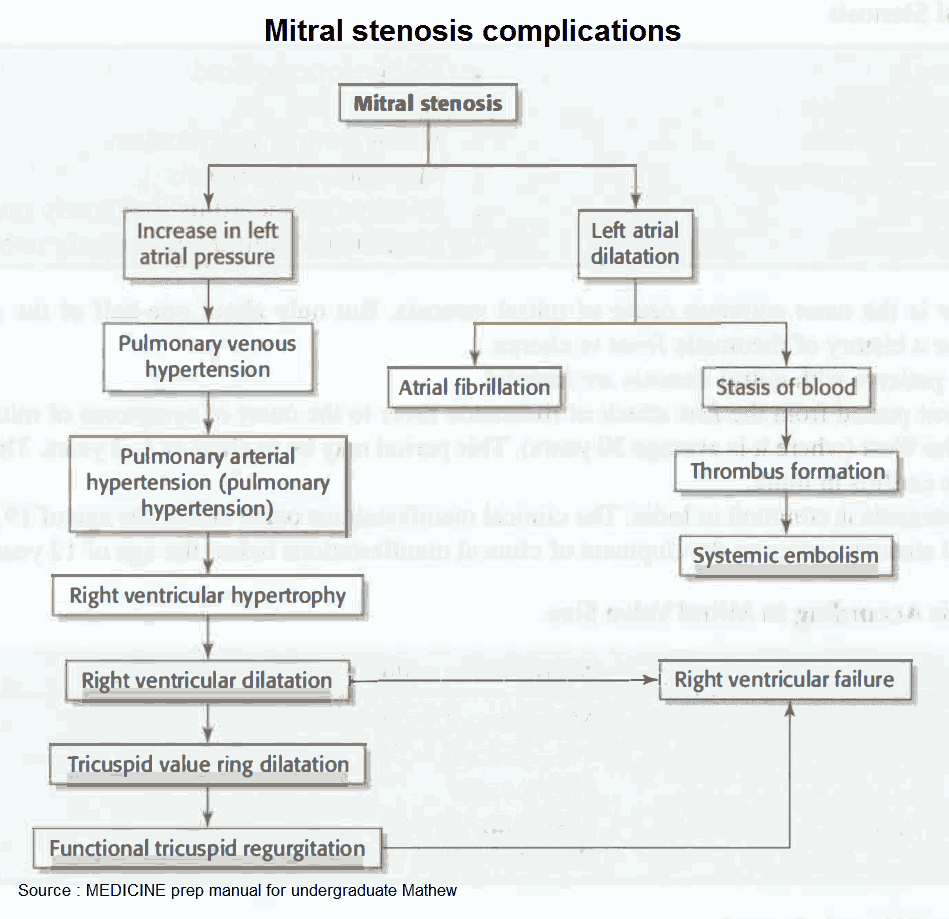

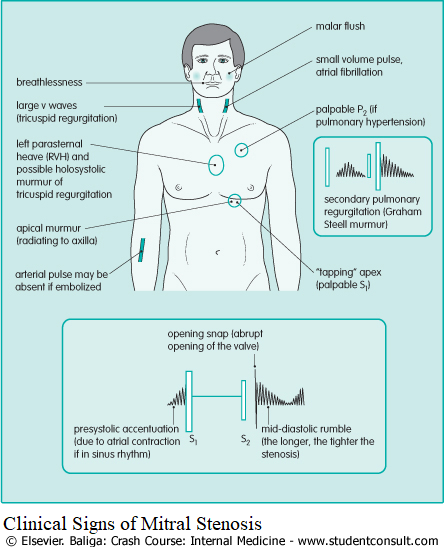

1. Mitral Stenosis

Mitral stenosis usually occurs in women with a history of rheumatic fever. The incidence has declined with the decline in rheumatic fever.

Causes of Mitral Stenosis

Clinical Symptoms of Mitral Stenosis

- Resistance in blood flow from the left atrium to the ventricle causes symptoms of left heart failure and eventual dilatation of the left atrium.

- Dyspnea on exertion is an early symptom, and may progress to orthopnoea and PND. Breathlessness often worsens considerably with the onset of atrial fibrillation, and is often accompanied by palpitations.

- Cough and hemoptysis may occur because of bronchitis, pulmonary infarction, pulmonary congestion, and bronchial vein rupture.

- Systemic emboli may occur in patients, particularly in atrial fibrillation.

- Fatigue and cold extremities are late symptoms, probably secondary to a low cardiac output.

- Chest pain occurs in a few people and may be due to coronary artery embolism or severe pulmonary hypertension. The patient may have coexistent coronary artery disease.

Clinical Signs in Mitral Stenosis

Differential Diagnosis of Mitral Stenosis

- Inflow obstruction (e.g., hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or left atrial myxoma)

- Aortic regurgitation

- Tricuspid stenosis

Diagnosis and Investigation of Mitral Stenosis

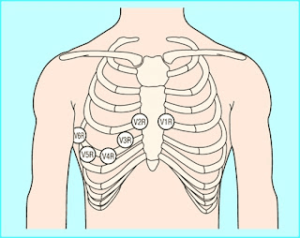

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) may show atrial fibrillation or “p” mitrale in sinus rhythm. There may be signs of right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH)-e.g., a dominant R wave in V1-and right axis deviation. The murmur of mitral stenosis is louder after exercise. Ask the patient to jog on the spot or do sit-ups on the examination couch if the murmur is soft.

- The chest x-ray (CXR) shows left atrial enlargement visible as a double shadow behind the heart. Valve calcification may be seen in lateral projections. There may also be signs of pulmonary edema and a splayed carina.

- Echocardiography can be used to assess the area of the mitral valve orifice, and the gradient across the mitral valve. It can also be used to assess left ventricular function and measure the size of the left atrium, and the right-sided heart chambers. This is important in deciding who is eligible for mitral ballon valvotomy.

- Cardiac catheterization is usually reserved for patients with suspected coronary artery disease but can be used to measure the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure as an indirect gauge of left atrial pressure, and the left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP), and hence the gradient across the mitral valve. The measurements should be repeated after exercise if the right-sided heart pressures are normal.

Treatment of Mitral Stenosis

- For patients without symptoms, it is important to provide prophylaxis against endocarditis.

- For patients with any symptoms or signs of right ventricular hypertension, it is essential that the stenosis be relieved with balloon mitral valvotomy or surgery.

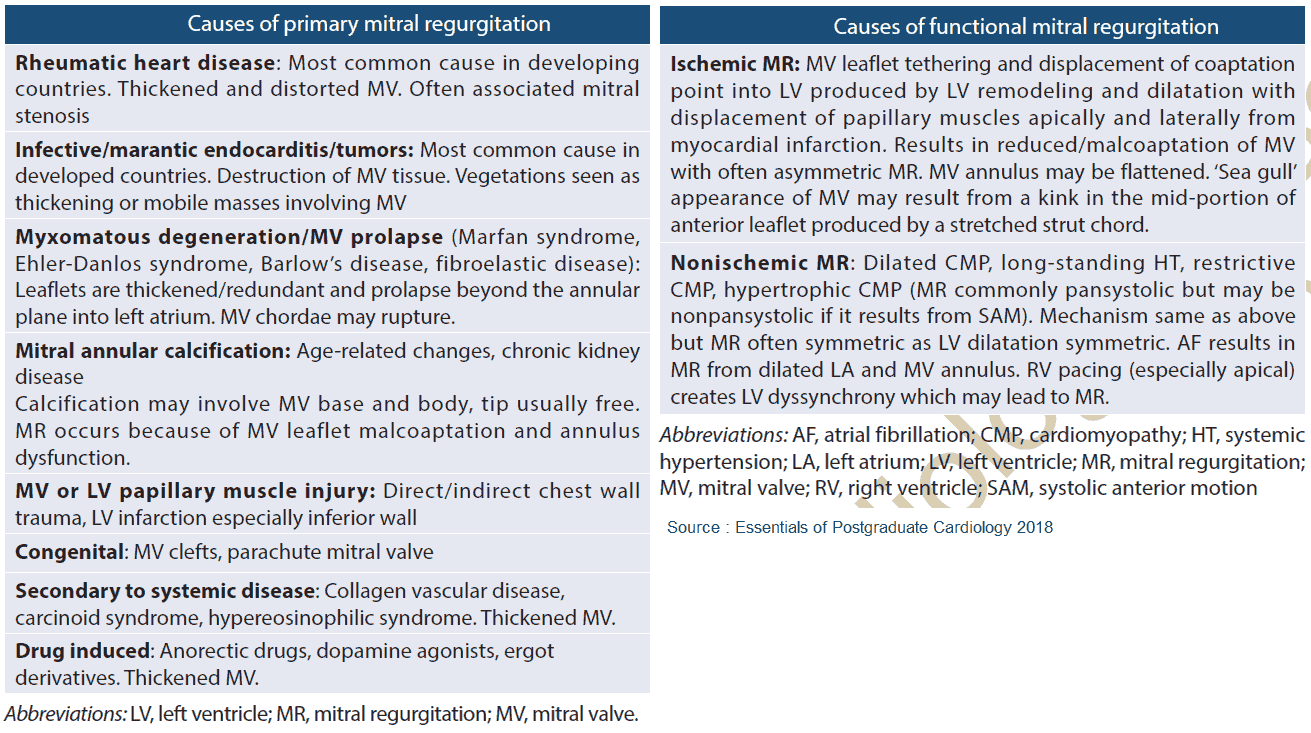

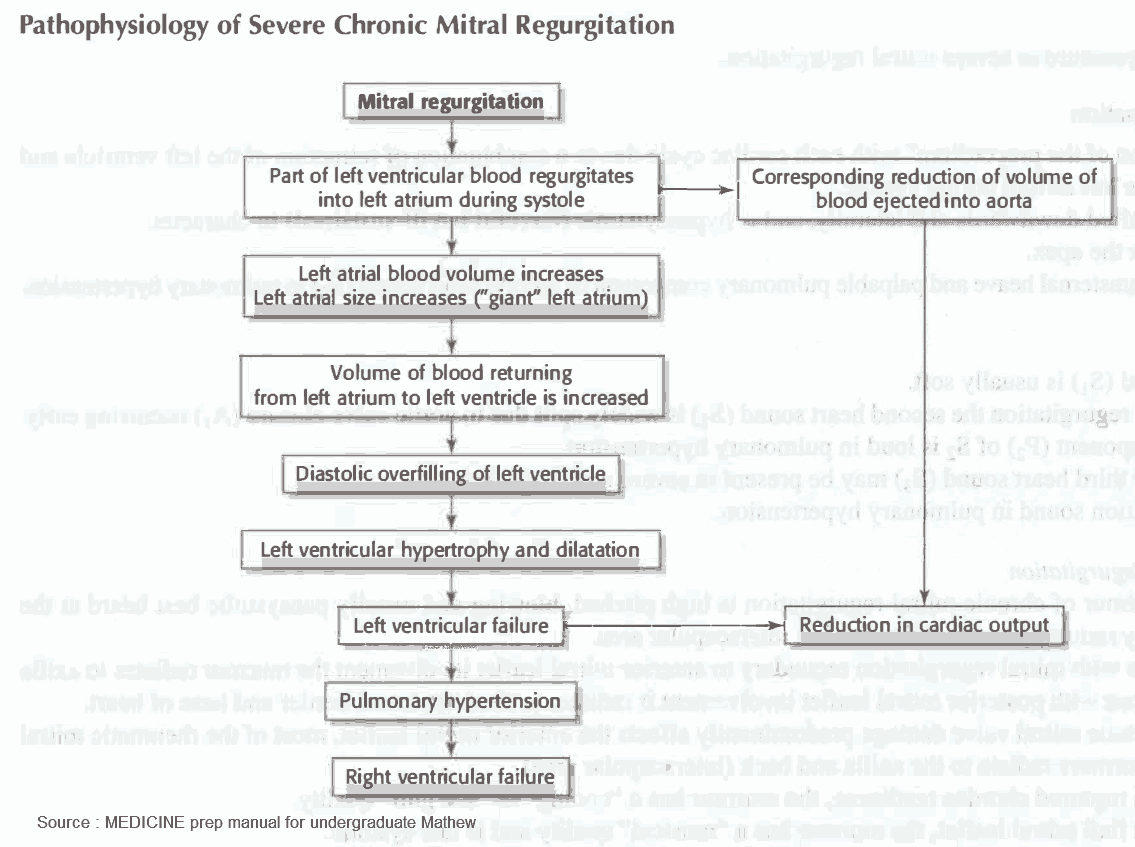

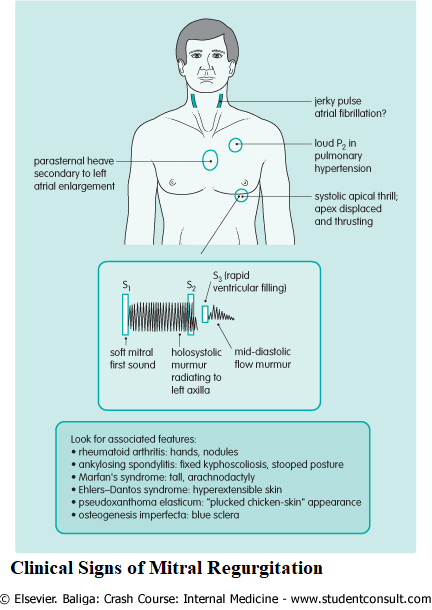

2. Mitral Regurgitation

Causes of Mitral Regurgitation

In a group of patients referred for surgery, mitral regurgitation (MR) was thought to be secondary to mitral valve prolapse (20-70%), ischemia (13-30%), rheumatic fever (3-40%), and endocarditis (10-12%).

Clinical symptoms of Mitral Regurgitation

Most patients with MR are without symptoms. Symptomatic patients may have progressive exertional dyspnea; palpitations, and fatigue are common, with symptoms of pulmonary edema if severe. Atrial fibrillation, systemic emboli, and chest pain are less common than in mitral stenosis.

Clinical Signs of Mitral Regurgitation

Differential Diagnosis of Mitral Regurgitation

The differential diagnosis of mitral regurgitation includes the following:

- Aortic stenosis

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- VSD

- Tricuspid regurgitation

Diagnosis and Investigation of Mitral Regurgitation

- The CXR shows cardiomegaly with enlargement of the left ventricle and left atrium. In acute mitral regurgitation the heart size is normal with signs of pulmonary edema.

- The ECG may show signs of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), “p” mitrale associated with left atrial hypertrophy, and occasionally atrial fibrillation.

- Echocardiography may reveal a cause for the regurgitation and can be used to assess the degree of left ventricular dilatation, which is useful for following the progress of the regurgitation.

Treatment of Mitral Regurgitation

Usually patients remain asymptomatic and do not require any intervention. Medical therapies have proved of little benefit for patients with MR. Patients with severe MR or with an acute presentation secondary to infectious endocarditis or ischemia often need mitral valve repair or replacement.

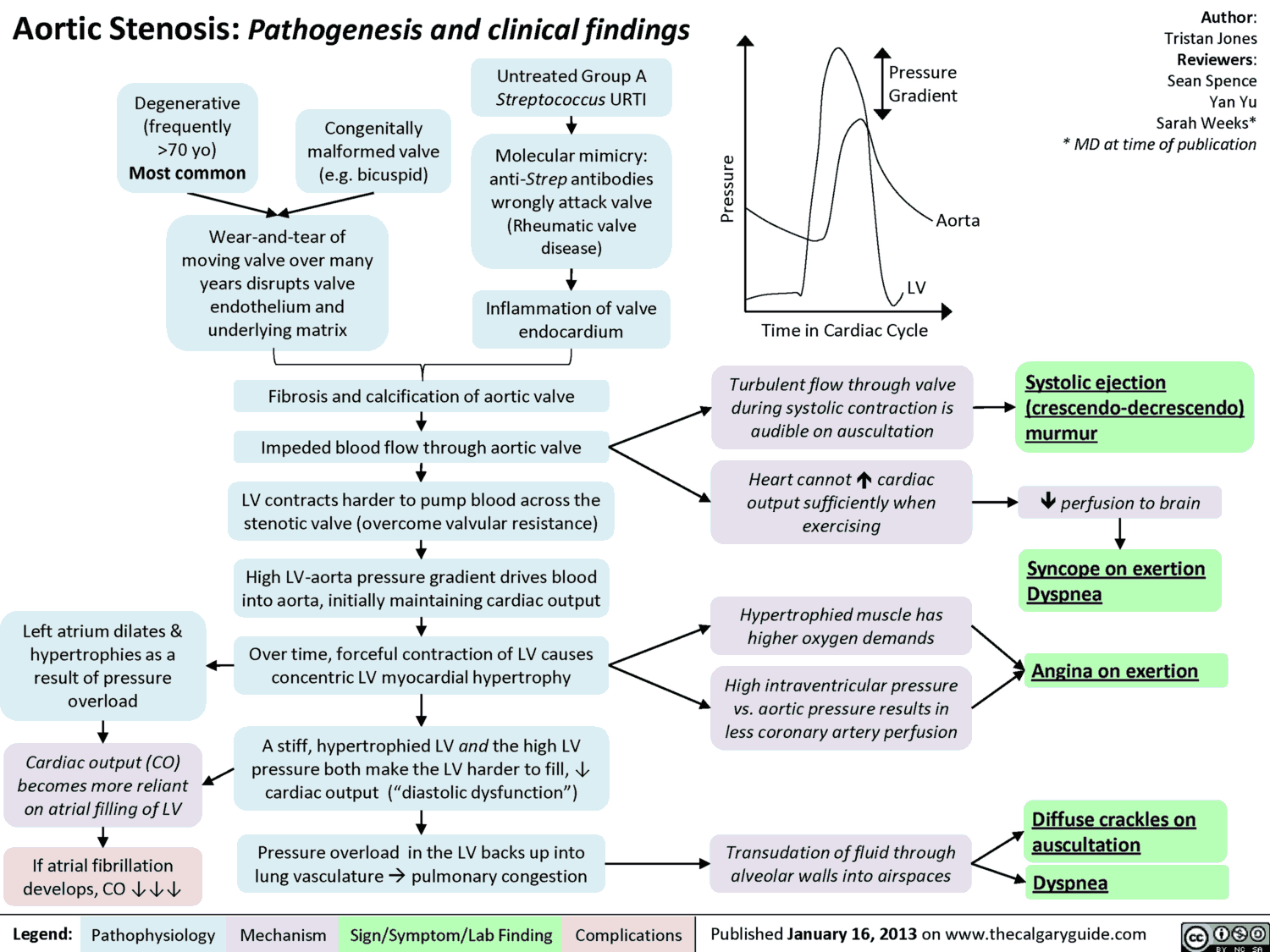

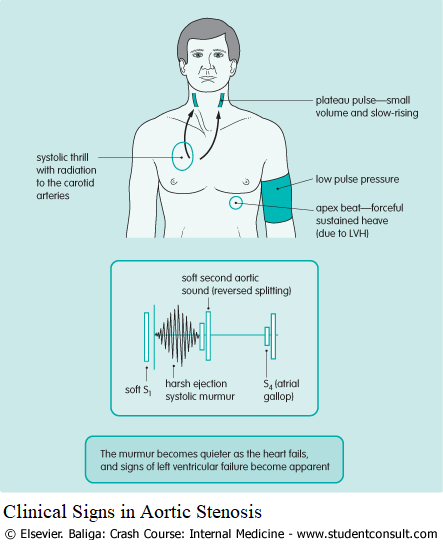

3. Aortic Stenosis

Clinical Symptoms of Aortic Stenosis

Initially the patient may be asymptomatic. Classically late symptoms are angina pectoris, syncope, and signs of heart failure (dyspnea). With these symptoms, the mean survival time is 5, 3, and 2 years, respectively, Sudden death may occur, probably secondary to ventricular dysrhythmias.

Clinical Signs in Aortic Stenosis

Diagnosis and Investigation of Aortic Stenosis

- The ECG shows signs of LVH with increased QRS voltages and ST/T segment changes.

- The CXR usually shows a normal heart size. The ascending aorta may be prominent due to poststenotic dilatation, and the valve may be calcified.

- Echocardiography may show a calcified valve and can be used to estimate the valve area. Cardiac chamber dimensions can be assessed, and doppler studies can be used to assess the gradient across the valve.

- Cardiac catheterization is usually only necessary to exclude coexisting coronary disease but can determine the systolic gradient across the valve.

4. Aortic Regurgitation

Clinical symptoms of Aortic Regurgitation

The patient is usually asymptomatic until the ventricle fails, giving rise to symptoms of heart failure. Angina rarely occurs.

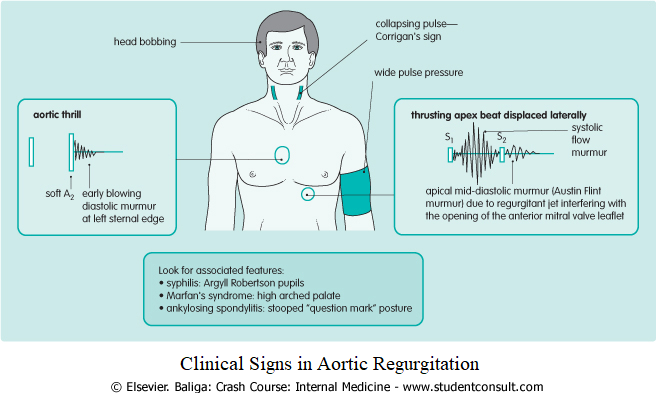

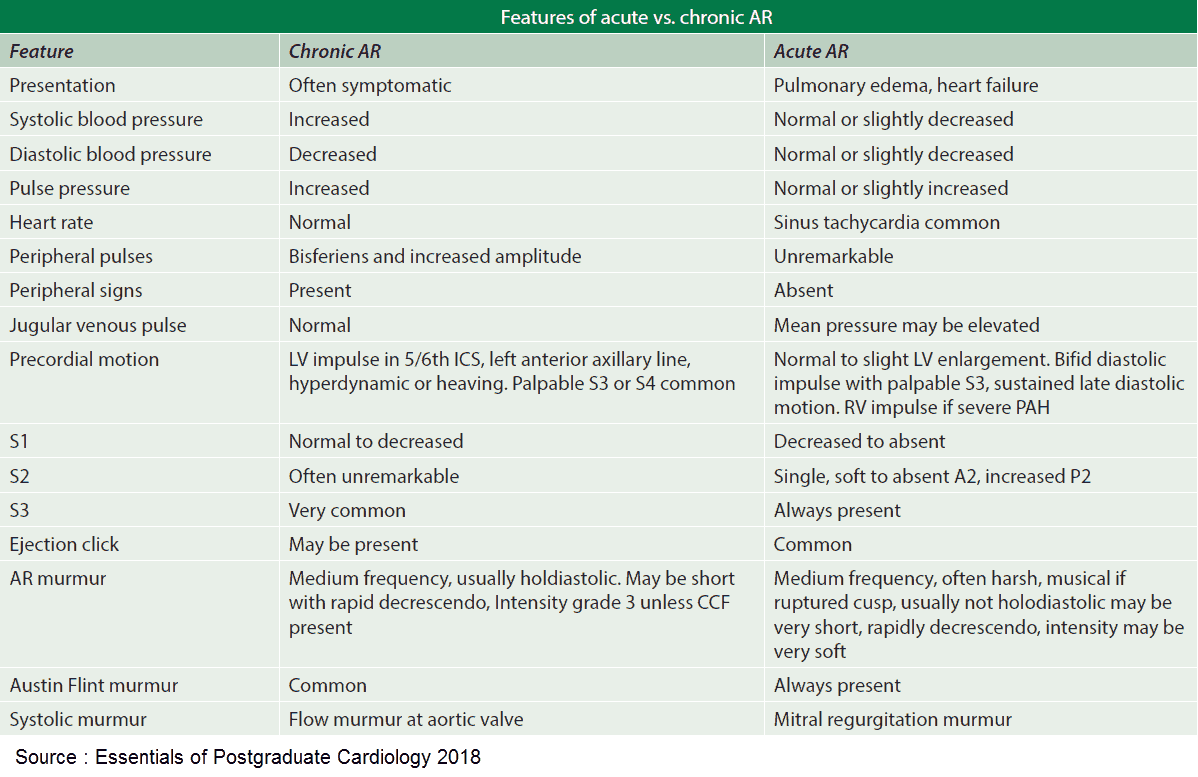

Clinical Signs in Aortic Regurgitation

- The pulse has a sharp rise and fall (“collapsing” or “water hammer”) with a wide pulse pressure

- Visible pulsation in the nail bed (Quincke’s sign)

- Visible arterial pulsation in the neck (Corrigan’s sign)

- Head bobbing (de Musset’s sign)

- “Pistol shot” femoral artery sound (Traube’s sign)

- Diastolic murmur following distal compression of the artery (Duroziez’s sign)

Differential Diagnosis of Aortic Regurgitation

The differential diagnosis of aortic regurgitation includes the following:

- Pulmonary regurgitation

- PDA

- VSD and aortic regurgitation

- Ruptured aneurysm of the sinus of Valsalva

Investigations of Aortic Regurgitation

- The ECG shows signs of LVH.

- CXR reveals cardiomegaly.

- Echocardiography can assess chamber size and may give a clue to the etiology.

- Cardiac catheterization can be used to assess the severity of the regurgitation, assess ventricular function, and for coronary arteriography.