With the development of the ventricular assist device (VAD), patients with end-stage cardiac failure now have an increased survival rate and improved quality of life.

Indications for placement of a VAD

- as a bridge to recovery in patients whose cardiac function is temporarily diminished (i.e., myocarditis)

- as a bridge to cardiac transplantation

- as destination therapy for patients who are not candidates for cardiac transplantation

The left ventricular assist device (LVAD) is the most common VAD in clinical practice, though a right ventricular assist device (RVAD) and a biventricular assist device (BiVAD) are also available. A well-coordinated multidisciplinary team manages VAD patients.

Notwithstanding, these patients will develop complications from the device that require emergency department (ED) evaluation and treatment. As such, it is imperative for the emergency provider (EP) to have a systematic approach to the evaluation of these complex patients.

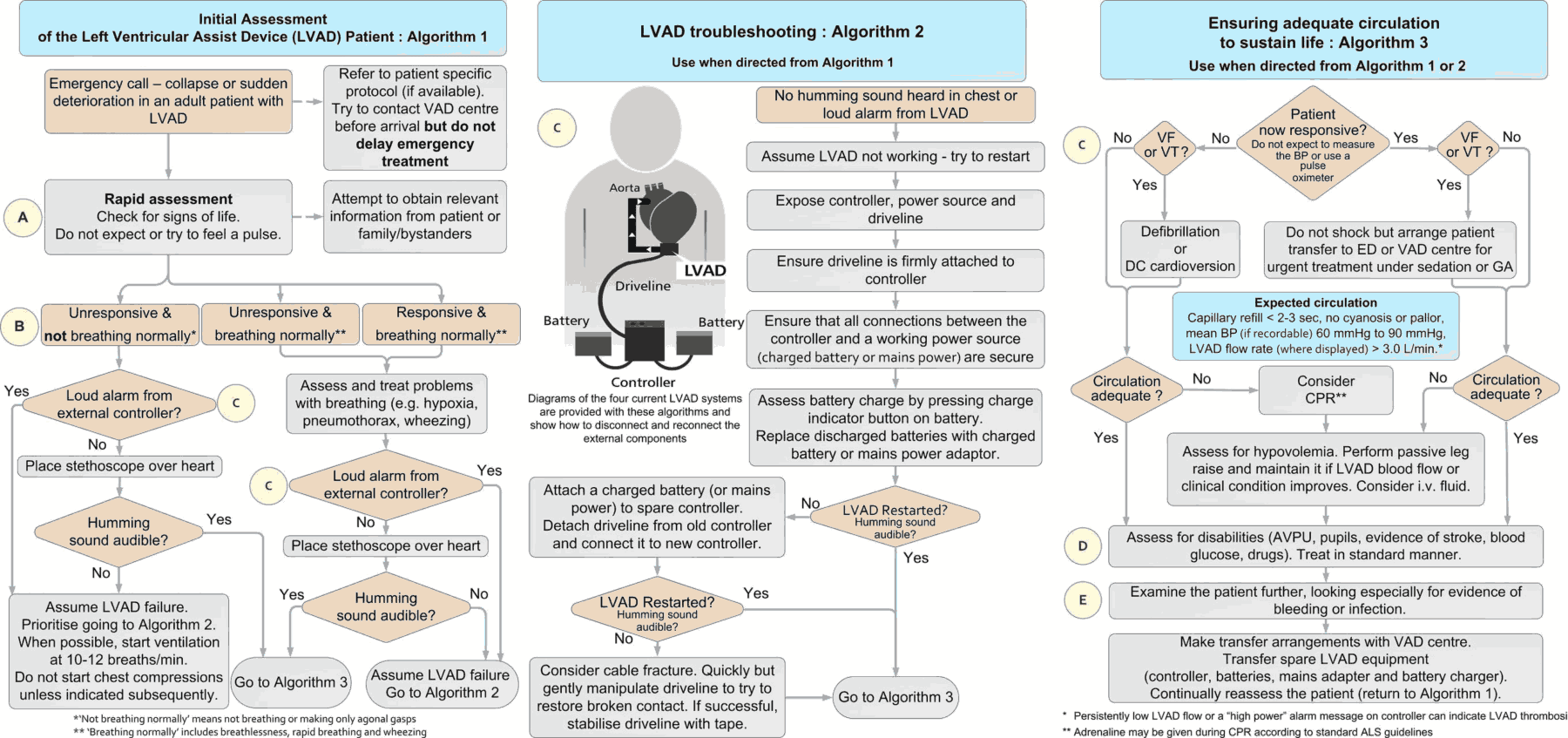

ED Evaluation of a VAD Patient

The ED evaluation of a VAD patient should begin with assessment of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation.

Pulse

Current VA devices deliver a continuous flow of blood to the patient. As a result, a pulse is often absent or markedly diminished.

Blood Pressure

Noninvasive systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements may be inaccurate or simply not obtainable.

For VAD patients, the mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) can be obtained with a blood pressure cuff and Doppler ultrasound over the brachial or radial artery. The cuff should be inflated until flow ceases on the Doppler device. The cuff should then be slowly deflated. Auscultation of the first flow signal indicates the patient’s MAP. The target range for MAP in VAD patients is 70 to 90 mm Hg.

An arterial line should be considered in the VAD patient who appears critical or moribund. It is also important to evaluate additional signs of peripheral perfusion, such as mental status, skin color and warmth, and urine output.

Chest Auscultation

The patient’s chest should be auscultated to determine the presence, or absence, of the continuous hum of the VAD. The absence of an audible hum suggests catastrophic VAD dysfunction and the need for immediate resuscitation.

Echocardiography (echo)

Bedside echocardiography (echo) is an invaluable tool in the ED evaluation of VAD patients, especially those who appear critically ill. Echo can be used to evaluate for pump thrombosis, right ventricular (RV) failure, and “suction” events.

Speed, Flow, Power, and Battery Life of the VAD

Additional components of the VAD that should be included in the initial assessment are the speed, flow, power, and battery life of the device. These values are found on the VAD monitor. Once the initial assessment has occurred, the patient’s VAD coordinator should be contacted to assist with management.

Complications in Patients with VAD (Ventricular assist device)

- Atrial or ventricular dysrhythmias

- Pump thrombosis

- Right ventricular (RV) failure

- “Suction” events

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Cardiac arrest

Atrial or Ventricular Dysrhythmias in VAD Patients

Atrial or ventricular dysrhythmias can occur in up to 50% of VAD patients. As such, it is important to obtain an electrocardiogram (ECG) in most VAD patients.

Common etiologies for dysrhythmias include hypovolemia, electrolyte derangements, and myocardial ischemia.

VAD patients who are unstable due to a dysrhythmia should be cardioverted or defibrillated. It is recommended to place the defibrillation pads in an anterior and posterior position.

VAD patients who are stable yet have a concerning dysrhythmia can receive antiarrhythmic medications. These patients should also receive intravenous fluids and, if necessary, electrolyte replacement.

Pump Thrombosis in VAD Patients

Pump thrombus occurs in up to 2% of patients within 2 years after VAD implantation. Pump thrombosis reduces cardiac output, which results in an elevation in the pump power reading. VAD patients with suspected thrombosis should receive anticoagulation with heparin.

Right Ventricular (RV) Failure in VAD Patients

Acute RV failure can occur in up to 25% of VAD patients and is usually seen soon after implantation.

“Suction” Events

VADs are preload-sensitive devices. In low-flow states, the negative pressure produced by the VAD can cause leftward displacement of the intraventricular septum and produce a “suction” event.

Suction events usually result from hypovolemia, but they can also occur with cardiac tamponade, dysrhythmias, and malposition of the inflow cannula.

Initial management of a suction event includes intravenous fluids, echo, and arrangement for transfer to a VAD center to evaluate the inflow cannula.

Bleeding in VAD Patients

Bleeding is an important and common complication that occurs in up to 40% of VAD patients.

All VAD patients are placed on anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications to decrease the rate of thromboembolic events. In addition, these patients develop an acquired von Willebrand syndrome in response to shear forces from the VAD. Finally, the decreased pulse pressure of the continuous flow contributes to arteriovenous malformations, especially in the jejunum.

VAD patients who are unstable due to hemorrhage should receive blood products and agents to reverse anticoagulation. Anticoagulation reversal in a stable VAD patient, however, should be done in consultation with the patient’s VAD team.

READ MORE : Reversal of Anticoagulant Therapy

Infections in VAD Patients

VAD patients are at high risk for infection. Infection can occur anywhere along the VAD including the surgical site, driveline, pump, or device pocket.

VAD infections can be caused by a variety of organisms, including grampositive organisms, especially coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative organisms, and fungi.

Critically ill VAD patients should receive broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover both grampositive and gram-negative organisms.

Cardiac Arrest in VAD Patients

Rarely, VAD patients may present in cardiac arrest. In these patients, the controller should be quickly evaluated for battery life and proper connections. Echo should be used to evaluate for pericardial effusion, left ventricular (LV) function, or RV dilatation.

Most VAD manufacturers state that cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be done only if absolutely necessary, primarily due to concern of dislodgement of the inflow cannula from the LV.

The only literature that exists on CPR for the VAD patient is a recent retrospective analysis of eight VAD patients who received CPR. In this study, no patient experienced dislodgement of the device with a 50% survival rate with good neurologic outcome.

VAD patients are a special challenge for the EP. Through a careful assessment of the VAD, physical exam, MAP, ECG, and echo, the EP can resuscitate the good VAD that has gone bad.

Key Points

- Contact the patient’s VAD coordinator as soon as possible.

- Obtain an ECG early to evaluate for dysrhythmias.

- Consider bleeding and sepsis in any critically ill VAD patient.

- Use echo to assess for pump thrombosis, RV failure, and suction events in the VAD patient.

- CPR is reasonable in the VAD patient in cardiac arrest.

Suggested Readings

- Partyka C, Taylor B. Review article: ventricular assist devices in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26(2):104–112. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24707998/

- Pratt AK, Shah NS, Boyce SW. Left ventricular assist device management in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:158–168. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24240731/

- Shriner Z, Bellezzo J, Stahovich M, et al. Chest compressions may be safe in arresting patients with left ventricular assist devices (LVADs). Resuscitation. 2014;85(5):702–704. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24472494/